Herbert and The Temple: Reading Through Religious Experience

English devotional poetry of the seventeenth century might seem worlds away from the experiences of a twenty-first-century reader. As Elizabeth Davis writes in this tour of George Herbert's temple, it is worlds away - but that's exactly what makes it such engrossing poetry. In this essay, written when she was in her second year of studying English at Cambridge, she guides the reader through some of the key poems in Herbert's collection, showing how the links between poetry and religious meditation raise important questions about metaphor and the privacy of reading.

'The Altar'

After entering through , one of the first ports of call in Herbert's temple, or church, is the Altar: the place of sacrifice and offering. The altar is where Jesus offers his own body to the faithful in the Eucharist and where the faithful offer Jesus their devotion. As a Protestant, however, Herbert did not believe in transubstantiation (the process whereby the Eucharist wafer becomes the body of Christ); the Eucharist remains a symbolic ceremony and so the altar, by extension, also becomes symbolic rather than literal (as in Catholic doctrine). As a result, Herbert already has a degree of freedom in talking about the altar: despite its material existence the altar's metaphorical nature, for Protestants, creates ambiguity which leads to and allows Herbert's metaphorical treatment of this part of the church.

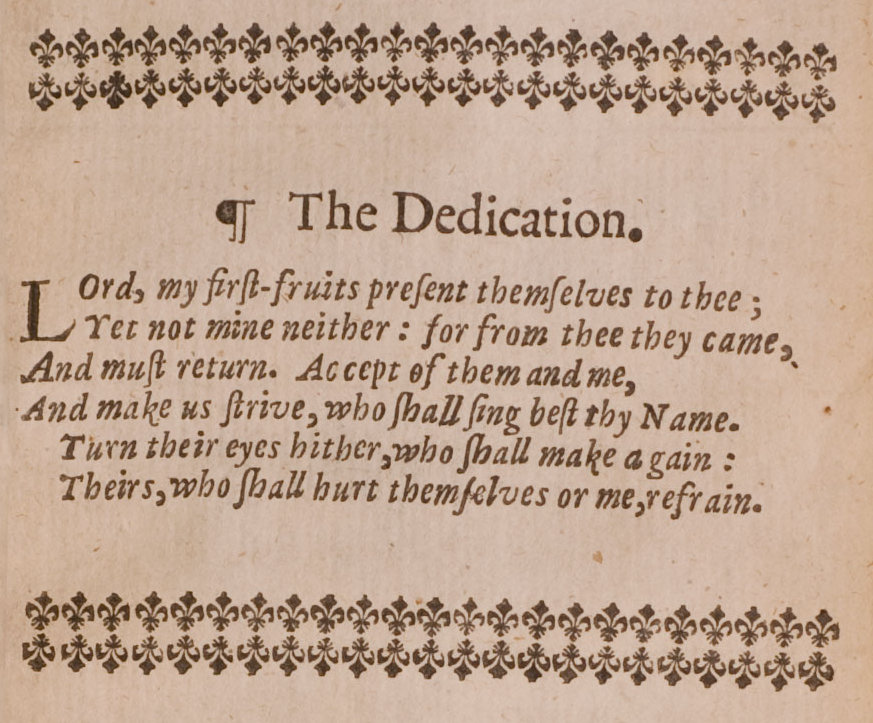

The title page of the 1638 edition of George Herbert's The Temple: Sacred Poems, and Private Ejaculations. This fifth edition in five years testifies to the popularity of Herbert's devotional poetry.

The first of the collection's , this short poem physically represents both the place of offering and an offering in itself. Herbert's role as a priest becomes absorbed into his role as a poet as he leads the reader in prayer, as a priest would a congregation: 'A broken altar, Lord, thy servant reares', he writes, where 'servant' refers to both the poet-priest and the reader. 'The Altar' is very early on in the collection and the role of the poet is still, at this stage, to guide the 'dejected poor soul' by the hand towards God. The poem is astonishingly non-specific and impersonal, a far cry from the passionate outpourings of the later parts of the collection: the personal pronoun 'I' is only used once and the phrase 'thy servant' is deliberately ambiguous. Like a prayer learnt by heart, this poem could be recited by anyone, or on behalf of anyone.

And yet Herbert's choice to set out the poem in the shape of an altar immediately moves the poem into the private sphere: the fact that the visual impact of the poem - experienced by a single reader - plays such an important role in the overall impact of the work demonstrates the private nature of poetical (as opposed to liturgical) devotion. Furthermore, Herbert first circulated the poem in manuscript form - when he handed it to his friend, Nicholas Ferrar, on his deathbed - a much more private means of transmission than that of print. Manuscripts had to be copied by hand, while printed texts could be reproduced exactly over and over by machinery. In the Tudor court, print had been shunned by some poets for its ; Herbert, however, wanted his poems published, saying they might "turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul". (Izaak Walton, The Life of Mr George Herbert) Print clearly has its advantages for Herbert's work: it can be spread, preaching his beliefs to a wide congregation even after his death. On the other hand, print's generality might detract from the private, prayer-like nature of poems such as 'The Altar'. A tension between public and private devotion persists, then, in Herbert's compositional choices: the private attention Herbert wishes to give the reader is maintained still in the visual shape of the poem: the poem can only have its full effect seen up-close by an individual reader, something which recalls its manuscript origins.

The poem is both an act of devotion by the poet and the reader, and a visual focus for that devotion, like a painting or a crucifix above the altar. The poem is, in essence, a work of art, painstakingly constructed by the artist, Herbert, who uses rhyme instead of mortar and words instead of stone. The shape of the poem is maintained through the rhyme Herbert uses: for example, in the couplet, 'A heart alone/ Is such a stone', the strong rhyme marks the end of each line and maintains the division which creates the shape of the poem (an altar) on the page.

One definition of the word 'altar' in the Oxford English Dictionary is 'a metrical address or dedication, fancifully written or printed in the form of an altar' and although this definition of the word is first used around 1680 (fifty years after the publication of The Temple), it is likely that Herbert's poem 'The Altar' gave rise to it. By constructing the poem in the shape of an altar Herbert mirrors the work of God as creator: as God created the physical world and everything in it, Herbert creates an echo of the physical world through his concrete poem. However, the altar of the poem is not restricted to a literal sense: the altar, we are told, is 'made of a heart and cemented with teares'. In one of Paul's letters to the Corinthians he writes 'know ye not that your body is the temple of the Holy Ghost' (1 Corinthians 6:19), a sentiment which Herbert literalizes in this poem: if the body is a temple, or church, the Altar would be approximately where the heart is. Although this is perhaps being too literal, Herbert clearly wishes to emphasise the metaphor of the body as a place of worship: the poem repeatedly refers to parts of the body, from the 'hand', to the 'heart'.

The word 'altar' appears in both the first and last lines of this poem; by the end of the poem, however, the word encompasses not only the High Altar, but also this poem and the heart itself: our understanding of the term has changed considerably and so Herbert's education of the reader continues.

'The Church-Floore'

In the cathedral of Siena, Italy you can find one of the most intricate church floors anywhere in the world. Created from 1372 to 1547 by the most talented artists in Siena (including Beccafumi), the large marble inlaid panels depict biblical stories, fables and intricate patterning. Where Herbert writes, metaphorically, of the church floor that 'that square and speckled stone,/ Which looks so firm and strong,/ Is Patience', the floor in Sienna literally depicts a fable of patience or humility, confidence or love. As in 'The Altar', this poem takes a physical part of a church and applies an allegorical status to it. In this case, sections of the floor stand for virtues ('Patience', 'Humilitie', 'Confidence', 'Love' and 'Charitie') and Sinne and Death act out an allegory over them. Herbert's church floor, more broadly, becomes a metaphor for a solid grounding, or foundation, in faith.

Like many of Herbert's poems, 'The Church-Floor' owes much to the King James Bible (first published in 1611). Herbert's constant use of italics recalls, at least visually, the use of italics in the King James Bible. Secondly, the use of allegory to communicate a moral is a key biblical characteristic, as, for example, in the parables told by Jesus and his disciples. The reference to God as the 'Architect', however, allows for the final allegorical level to be added by Herbert. Until the final line the reader believes the church and the floor to be actual, even if imbued with an allegorical layer; in the wording of the final lines - 'Blest be the Architect, whose art/ Could build so strong in a weak heart' - it becomes clear that, just as 'The Altar' finally comes to mean the heart, so the whole church, the entire place of worship in 'The Church Floore', is located within the human body - within the heart.

'Mark you the floor?' is thus not simply a question, but a challenge, a hint that we should notice and appreciate the true nature of the ground beneath us. The virtues Herbert enumerates form the foundation of faith, his suggestion being that we had not noticed such virtues within ourselves because we had never looked for them. What makes the floor of Siena's cathedral so enchanting is its demand for attention: other Italian cathedrals have beautiful floors but they are unobtrusive and visitors do not 'mark' them. In Siena the visitor cannot help but 'mark' the floor; like Herbert, the artists of the marble panels wanted to draw our attention to something which is always there ('Love' or 'Confidence') but is rarely appreciated. But unlike Beccafumi, Herbert insists in 'The Church-Floore', as in 'The Altar', that the true ground of faith lies not in stones but in the self.

'The Storm' and 'Love'

These two poems herald a new direction within The Temple: the poet-priest of 'The Altar' is replaced with a very human, fallible poet-persona who has 'sighs and tears' and is 'Guiltie of dust and sinne', like everyone else. Moreover, while 'The Altar, 'The Church-floore' and the 'The Windows' (another poem from The Temple) all deal with material objects, at least as a starting point, 'The Storm' and 'Love' take as their subject forces much less tangible.

Perhaps the most effective element of these poems is the tight form which Herbert uses to express psychological turmoil. The strict AABBCC rhyme scheme of 'The Storm' echoes the bands by which the poet-persona feels himself bound: his frustration beats against the line endings as waves beat against the sea wall. The enjambment found in the opening couplet - 'If as the windes and waters here below/ Do flie and flow' - expresses the persona's feeling of claustrophobia and attempts to break free. A more powerful enjambment occurs across couplets later in the first stanza ('Sure they would move/ And much affect thee'), but by the final stanza all but one of the lines are end-stopped. Like the metaphorical storm, the rage of the persona has calmed by this point: 'Poets have wrong'd poore storms: such days are best;/ They purge the aire without, within the breast'. Herbert slows done the penultimate line with additional punctuation and adds the pleasing symmetry of 'without, within' in the final line to suggest a restored harmony, the calm after the storm. The use of zeugma here, joined to a transition from the exterior ('without') to the interior ('within'), further emphasises the way in which order must be received by the poet, rather than achieved.

Whilst the tone of this poem is not as formal as some of the others in the collection, it could still be called 'prayer-like'. The poet addresses God in a very personal and informal manner, as in these lines, where the poet-penitent threatens heaven with his impudence: 'It quits the earth, and mounting more and more,/ Dares to assault thee, and besiege thy door'. If 'The Altar' presents the reader with a public prayer spoken by a poet-priest, 'The Storm' represents a much more private, emotional prayer. Our role in relation to this prayer is that of an eavesdropper, rather than a fellow supplicant. Herbert has switched from lending the reader a guiding hand to sharing his experience, as he told Nicholas Ferrar on giving him the manuscript: '[the book contains] a picture of the many spiritual Conflicts that have past betwixt God and my Soul, before I could subject mine to the will of Jesus my Master'. (Izaak Walton, The Life of Mr George Herbert)

The apparent sincerity of this poem is somewhat belied, however, by the fact that it is a printed poem. Although never printed in his lifetime, Herbert passed the manuscript of The Temple to a friend with a request that he publish it. Our role as eavesdropper, then is a false one, for Herbert wrote the poem for public consumption. 'Love', on the other hand, does not claim to be a prayer: there is no addressee, aside from the reader - it is unequivocally a poem, albeit a spiritual one. The final poem in the collection, 'Love' describes the poet-persona's relationship with God in terms of a shared meal. Coming at the end of 'The Temple', it signifies an assumption that we now share Herbert's Christian belief and offers a glimpse of the final reward of faith: an existence with God, in Heaven. For the first time in the collection, Herbert addresses the reader directly; after having prayed with him, witnessed his crises and enjoyed his artfulness, Herbert finally addresses the reader as an equal.

'The Collar'

The Collar takes its tone from its elegantly ambiguous title: a collar is both a badge of Herbert's profession in the clergy and a restraint used on an animal. Both senses are key to an understanding of this passionate poem. The poet-persona cries 'No more' to what he feels is a life lived in 'a cage', dictated by Divine Will; what follows is an outpouring, an explosion of questions and exclamations with the professed aim to break out of this 'cage'.

Line lengths vary from ten to four syllables seemingly at random, giving the impression of a mind in turmoil; the short lines in themselves suggest breathlessness and impatience: 'Away; take heed:/ I will abroad'. The frankness with which Herbert presents this spiritual crisis contributes to the sense of self, not only in this poem, but in the collection as a whole. For the 'dejected poor soul' who may be reading this poem the message is an encouraging one: even a clergyman occasionally finds submission to the Divine Will a difficult task.

The poem is, however, recalled in tranquillity: this rage was in the past and the seeming chaos is only an illusion. For example, although the variation in line length appears arbitrary and random at the outset of the poem, by the end, it has been resolved into a clear alternating pattern. Herbert is implying that, like the pattern, the will of God has been there all along but was incomprehensible until - for both the reader and the poet - it was made evident by experience.

'The Collar' demands a very particular role from the reader: we should recognise ourselves in the persona's frustration and finally submit, as the persona does, to God's will. In short, this poem demands that the reader share the Christian faith of the poet: that's not to say that it can only be enjoyed by Christians but rather that if we are to feel a satisfactory sense of conclusion in the final lines, we must accept God's existence as fact. To a non-Christian reader the final lines communicate a sense of calm and peace: 'Methought I heard one calling, Childe:/ And I reply'd, My Lord' but leave, perhaps, a sense of something unexplained.

Chaos is restored by the intervention of God: a gentle nudge from the Divine Being to the poet. In this more sceptical age Herbert's poetry can sometimes be hard to understand or unapproachable but Herbert's continual demands on the reader's attention and interaction make him a strikingly open and honest poet, whatever your cultural background.

Further Reading

- The English Poems of George Herbert, ed. Helen Wilcox (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- Izaak Walton, The Life of Mr George Herbert, in The lives of Dr. John Donne, Sir Henry Wotton, Mr. Richard Hooker, Mr. George Herbert, 1670 (Menston: Scolar Press, 1969).

- 'George Herbert', in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, http://www.oxforddnb.com

- http://www.sacred-destinations.com/italy/siena-cathedral-duomo-di-santa-maria.htm

- Elizabeth Clarke, Theory and Theology in George Herbert's Poetry: 'Divinitie, and Poesie, Met' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997).

- Stanley Fish, Self-Consuming Artifacts: The Experience of Seventeenth-Century Literature (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972), ch. 3.

- Louis Martz, The Poetry of Meditation: A Study in English Religious Literature of the Seventeenth Century, rev. edn (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962).

- Michael Schoenfeldt, Prayer and Power: George Herbert and Renaissance Courtship (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

- Richard Strier, Love Known: Theology and Experience in George Herbert's Poetry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

- J. W. Saunders, 'The Stigma of Print', Essays in Criticism, 1 (1951), 139-64.

- Joseph Summers, George Herbert: His Religion and Art (London: Chatto and Windus, 1954).

- Helen Vendler, The Poetry of George Herbert (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1975).

Further Thinking

The practice of expressing prayer - a deeply intimate experience for someone of religious faith - through a formal medium like poetry might seem, as Elizabeth Davis argues, to create a problem: are these poems private, personal essays, or generic, public performances? Does thinking about this problem within the context of George Herbert's seventeenth-century Anglicanism help you to understand poetry, and its problems of sincerity, more generally?

One of the recurring themes of Herbert's devotional poetry, Elizabeth Davis argues, is the transition from material to metaphorical icons, architectural spaces, and devotional aids. This transition from the material to the linguistic was consistent with Herbert's protestant faith, which stressed the importance of Scripture, reading, and interpretation in Christian spiritual life; but it may also give us access to broader ideas about the means and bases of understanding - both of the divine and of the self. Do you think poetry might be, as for Herbert, a good (the best?) tool or medium for thinking about our place in the world?

Elizabeth Davis' presentation of Herbert's poetry stresses its universality: although written by a Christian clergyman for an ostensibly Christian purpose, the ideas that pour out of Herbert's poetry seem to be of much wider, more universal significance. One of the most important of these, of course, is that of our relation, as readers, to the voice of a poem. How does reading Herbert's poetry help you to understand the ways in which a poem addresses, invites, manipulates, and even coerces its readers?