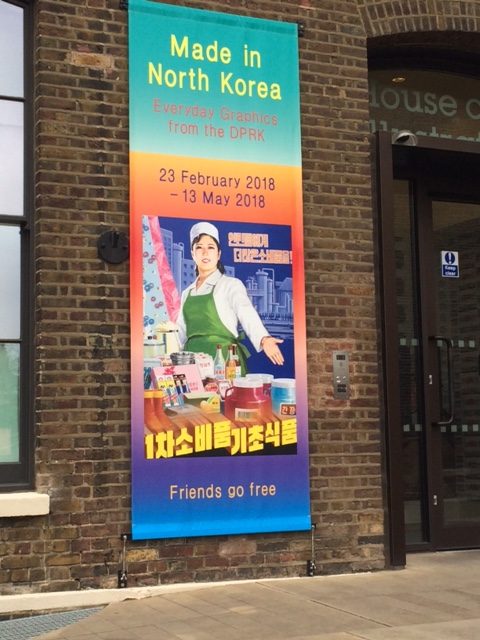

A unique collection of material texts currently on display at London’s House of Illustration gives a fascinating glimpse into everyday life in one of the most secretive modern states. Made in North Korea brings together posters, badges, food packaging, and comic book covers from the personal collection of Nicholas Bonner, who has led tours to the country for the last 25 years.

The artists who produce the posters, which promote the DPRK’s agricultural industries – ‘For a bumper crop, let’s send more chemical fertiliser to the countryside!’ and its political ideals – ‘With the full heart of a mother, let’s become good caretakers of the People’s lives!’ – are trained at state art colleges to paint in a particular style, using a distinctive palette of colours. The exhibition mixes posters from as early as the 1970s with much more recent ones from the last few years, and it is striking how little the style and conventions of these posters have changed over time.

The comic book covers are similarly unified, with titles such as ‘Woman Sniper’, ‘The Orders Must be Absolutely Fulfilled Until The End’, and ‘The Never-Ending Confrontation’ signalling their ideological purpose. Seeing what we usually think of as ephemeral material texts – labels for tinned fish and meat, sweet wrappers, and postage stamps – displayed alongside these explicit pieces of propaganda is a starkly colourful reminder of how even the disposable material texts of everyday life can be political.