As we reach the last few days of campaigning for the referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU, a pro-remain friend reports on Facebook that she has found a torn-up ‘IN’ poster outside her front door. Coming a few days after the murder of the Labour MP Jo Cox, this is scary stuff.

It may be harder to read the words on a torn-up poster, but its message is all too legible. It also reveals something important about the medium: about paper, with its susceptibility to tearing, to shredding, to violence–its palpability, which is also its palpable ability to act as a metaphor for the body. If you hate this blog post, you can leave an abusive message in response to it; you can troll me or mount a cyber-attack. But you cannot convey your anger through the universal language of the tear. Ripping the page to shreds is a micro-drama that is rapidly fading from our everyday life. The power of paper turns out to be its weakness, its disposability.

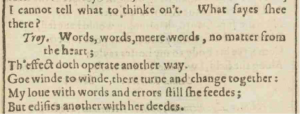

There are a few moments in Shakespeare that capture these aspects of paper. Amid the utter bleakness of the ending of Troilus and Cressida, Troilus receives a letter from Cressida. We never find out what it says; Troilus dismisses the contents as ‘words, words, mere words, no matter from the heart’, before tearing it up. ‘Goe wind to wind, there turn and change together’. The fluttering of the paper becomes a visual metaphor for what Troilus perceives to be his beloved’s faithlessness.

There are a few moments in Shakespeare that capture these aspects of paper. Amid the utter bleakness of the ending of Troilus and Cressida, Troilus receives a letter from Cressida. We never find out what it says; Troilus dismisses the contents as ‘words, words, mere words, no matter from the heart’, before tearing it up. ‘Goe wind to wind, there turn and change together’. The fluttering of the paper becomes a visual metaphor for what Troilus perceives to be his beloved’s faithlessness.

At a similar moment of trauma in Cymbeline, Imogen learns that her beloved Posthumus Leonatus wants her killed. She doesn’t yet know why this should be so, and guesses that he has met a new love; ‘Poor I am stale, a garment out of fashion, / […] I must be ripped: To pieces with me!’ She asks her servant Pisanio to get on with the job of stabbing her, and bares her heart to make the job easier. But she finds the way to her heart barred: ‘What is here? / The scriptures of the loyal Leonatus, / All turn’d to heresie?’ It turns out that she has been storing the letters inside her clothing, like a lining. In this case, she merely throws the letters away (‘Away, away / Corrupters of my faith, you shall no more / Be stomachers to my heart’). In a play that is full of images of bodily dismemberment, it matters that she doesn’t seem to rip them up, and that Pisanio refuses to rip her up. This is a play about restitution–the words will come together, and will be full of meaning once more, by the end.

Let’s hope the political sphere will see some similar restitutions in the coming days and months…