Today, on a beautiful sunny day, a large group of diehards shut itself up in a couple of rooms in Cambridge’s Faculty of Education to discuss ‘The Children’s Book as Material Object’. Events were initiated by a richly detailed keynote from Philip Nel, who took on Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon, which he read as a development of Paul Klee’s ideas about taking a line for a walk. Exploring every conceivable context including the history of crayons, the development of TV shows that encouraged children to write on the screen (using their ‘winky dink kits’), and the demands of offset chromolithography, he revealed how intricate was the construction of Harold. He also disinterred a subtle racial politics from Harold’s 10% brown skin, which some readers read as white and some as black. This ambiguity perhaps tied up with Johnson’s activities in the civil rights movement, for which he was under FBI investigation at the time that he was writing his book.

Today, on a beautiful sunny day, a large group of diehards shut itself up in a couple of rooms in Cambridge’s Faculty of Education to discuss ‘The Children’s Book as Material Object’. Events were initiated by a richly detailed keynote from Philip Nel, who took on Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon, which he read as a development of Paul Klee’s ideas about taking a line for a walk. Exploring every conceivable context including the history of crayons, the development of TV shows that encouraged children to write on the screen (using their ‘winky dink kits’), and the demands of offset chromolithography, he revealed how intricate was the construction of Harold. He also disinterred a subtle racial politics from Harold’s 10% brown skin, which some readers read as white and some as black. This ambiguity perhaps tied up with Johnson’s activities in the civil rights movement, for which he was under FBI investigation at the time that he was writing his book.

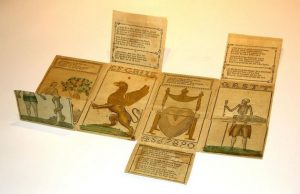

After this, the conference moved into parallel sessions. The one I attended took on the theme of play and interaction. Jacqueline Reid-Walsh delved into the history of playable media, showing some wonderful seventeenth- and eighteenth-century lift-the-flap books that allowed children to turn Adam into Eve, and Eve into a mermaid. Sandra Williams took us into the world of the –Ology series (Pirateology, Dragonology etc), bejewelled books that include all kinds of games that (in practice) lure their young readers into digressive play. The investigation of the responses of real schoolkids was also a feature of the final paper in the panel, in which Anne Neely and Noelle Yoo reported back on responses to their dinky 3D-printed posable figures of Elephant and Piggie, from the popular series by Mo Willems. If the book starts off as a self-contained reading experience, it seems that it has an afterlife in play, during which new stories are set loose.

After lunch, a second parallel session kicked off with Debbie Pullinger and Lisa Kirkham thinking (with help from Heidegger) about the differences between the tactile text of the physical book and the uncontained realm of the ebook. Naomi Hamer took on the proliferation of museums based on children’s books and children’s authors, noting that their curatorial aesthetic (images framed on walls, no touching please!) was radically incompatible with books that beg to be touched. And Tyler Shores explored the (mostly unsatisfactory) effort to translate comics to the ereader screen; the process of adapting a complex graphic medium to a new platform is presenting severe teething difficulties. All three accounts raised important questions about remediation, and how well books survive when they are translated to new environments.

The last, plenary session of the day had four papers. Sophie Defrance, from the University Library, discussed the blurred lines between children’s books and children’s toys and games in the library’s collections. Carl F. Miller called attention to the extraordinary power of literary prizes in the children’s book world, and noted that awards of comparable gravitas for ebooks have yet to emerge. Jen Aggleton reported on the responses of young readers to a set of illustrated novels, charting the process by which these 9/10-year-olds were awakened to the aesthetic pleasures of a well-crafted book. And Zoe Jaques took us deeper into the borderland between books and toys, where a variety of book-like ‘scriptive things’ create severe problems both of categorisation and of shelving.

The last, plenary session of the day had four papers. Sophie Defrance, from the University Library, discussed the blurred lines between children’s books and children’s toys and games in the library’s collections. Carl F. Miller called attention to the extraordinary power of literary prizes in the children’s book world, and noted that awards of comparable gravitas for ebooks have yet to emerge. Jen Aggleton reported on the responses of young readers to a set of illustrated novels, charting the process by which these 9/10-year-olds were awakened to the aesthetic pleasures of a well-crafted book. And Zoe Jaques took us deeper into the borderland between books and toys, where a variety of book-like ‘scriptive things’ create severe problems both of categorisation and of shelving.

Proceedings were wrapped up with a round-table, which offered an opportunity for broader reflection on the category of the scriptive thing and on the seeming self-containment of the book. For me, the day came neatly full circle, sending me back to the opening meditation on Harold and the Purple Crayon, which had revealed above all the extraordinary artfulness of the book’s construction. Modern children’s books, following Harold, are often triumphs of choreography, in which text and image work interact in very sophisticated ways. They are masterful in their handling of gaps and silences, teasing the child reader to make the necessary inferences (often with prompting from a nearby adult). And they constantly reinvent the book, offering new shapes and sizes and graphic conventions so as to pitch readers into weird and unpredictable worlds. It struck me that one of the reasons that we feel so nostalgic about children’s books is because they are so literary. They offer an intense foretaste of grown-up poems, plays and novels, in which the rules of the game are often similarly unclear, and the outcomes deliciously unpredictable.