Herron, Thomas, ed. Centering Spenser: A Digital Resource for Kilcolman Castle. East Carolina University, 2013.

Three words can describe Thomas Herron’s recently-published project Centering Spenser: spatial, material, and pedagogical. Designed to “center” the English poet in the southwestern Irish environment that became so crucial to his writing and imagination, the project features a 3-D model of Spenser’s castle at Kilcolman as its centerpiece. According to Herron’s project overview, this digital reconstruction was the work of many years and many hands at the University Multimedia Center at East Carolina University. Centering Spenser provides users with a gallery of 87 images from the castle renderings, a speculative interactive tour of the castle, historical maps of Kilcolman, and photographs of the castle as it appears today (the latter are especially helpful, as Google Maps has yet to reach the area; see figure 1). The website also features an abbreviated timeline of the poet’s life, as well as a substantial number of essays (all by Herron) on various topics including the Desmond Rebellion of 1579-1583 and Spenser’s relationship with the poet and statesman Sir Walter Raleigh.

Figure 1: Google Maps has yet to include full imagings of Kilcolman and the areas where Spenser’s castle ruins stand today.

This project’s focus on Kilcolman will attract interest in light of recent scholarship on Spenser’s Irish settlement and his prose tract A View of the Present State of Ireland (c. 1596). That a compromising portrait of Spenser emerges from this tract—that of an exasperated colonial administrator attempting to civilize the purportedly barbaric natives of Ireland—is not the primary interest of this site, however. Herron explains why in an “Overview” that functions more or less as the project’s editorial introduction:

Centering Spenser gives insights into the Munster Plantation by demonstrating aspects of Spenser’s experience there. The website does not apologize for, nor try to romanticize, Spenser’s role as colonial administrator and settler in Ireland. Instead, it attempts objectively, pragmatically and imaginatively to study his place in Munster near the center of the province and to better appreciate his works in relation to that situation.

Without ignoring or obscuring recent studies of Spenser’s Irish habitation and his discriminatory attitude toward the country’s natives, then, Centering Spenser aims to offer a material view of the poet’s life in Kilcolman that is useful to students, scholars, and general users alike. Indeed, with an Interactive Map of the region, the project connects Spenser’s settlement to political conflicts (this is a portion of the site with room to grow), as well as the poet’s writing, trade, and travel. Herron’s essays, positioned at relevant points throughout the site, also demonstrate the project’s debt to important works of scholarship, including Andrew Hadfield’s excellent new biography, Edmund Spenser: A Life (2012) and A. C. Hamilton’s invaluable Spenser Encyclopedia (1990). A textual counterpoint to the project’s dynamic 3-D renderings, these essays serve as a vital link between Centering Spenser and established, peer-reviewed research in print monographs and academic journals. This element of the project may appeal to the more traditional scholar of Spenser, his poetry, and Early Modern Ireland.

At the same time, Centering Spenser demonstrates the creators’ concerted efforts to situate the project within and among emerging networks of digital resources for Spenser Studies. This aspect of the project offers the greatest promise for growth, especially with the coming of Renaissance English Knowledgebase (REKn) and other federated, peer-reviewed networks for Early Modern research. At multiple points, Centering Spenser is already joined with Spenser Online, a website that hosts the International Spenser Society, The Spenser Review (which features its complete published materials online), and a bibliographical Finding Aid for editions of Spenser’s works in research libraries worldwide. Although the relationship between efforts like Centering Spenser and Spenser Online has yet to take a definitive shape, it is evident at this stage that the host site has room for other, similar-scaled digital projects.

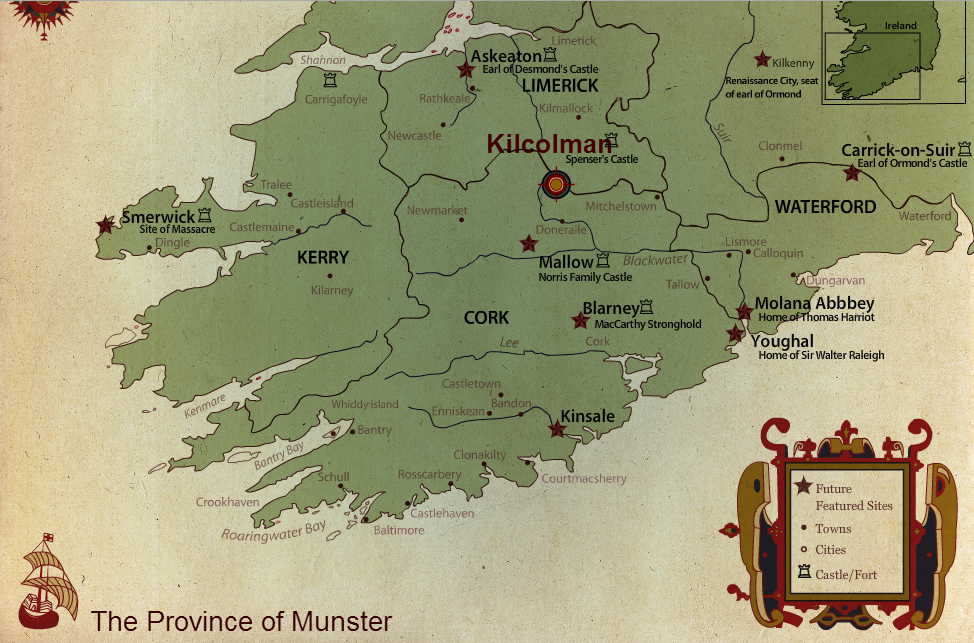

In an analogous manner, Centering Spenser itself has left space open for scholarly efforts that may be incorporated into its own digital infrastructure. This is especially clear in the website’s Interactive Map of the province of Munster, where users can see certain locations starred already as “Future Featured Sites” (see figure 2). The Massacre at Smerwick, Sir Walter Raleigh’s home at Youghal, and the Earl of Ormond’s castle at Carrick-on-Suir are only three of nine potential projects that could emerge from Centering Spenser and could be joined to its fabric. With gestures outward to other resources including Wordhoard, the Map of Early Modern London, and various electronic texts of Spenser’s works including those at Luminarium, Centering Spenser confidently locates itself among emerging digital projects. This dimension of the project should prove useful in the long run to undergraduates and to scholars preparing similar or contiguous projects.

Figure 2: Detail of Interactive Map of southwestern Ireland, with “Future Featured Sites” indicated with stars.

The project’s central contribution to Spenser Studies is a 3-D reconstruction of the Kilcolman Castle. This model is based eclectically upon the standing remains of the castle at Kilcolman and recent archeological excavations at the site undertaken in the mid-1990s by Eric Klingelhöfer and David Newman Johnson. The project also includes excavation plans from that effort. Kilcolman Today, a gallery of about twenty photographs of the castle site, gives users a sense of what it looks like in the present day (or roughly so; the images are sometimes as old as fourteen years, and Herron mentions certain changes over time, such as ivy growth). The website also includes a Historic Image Gallery with seven images of the castle over time and as represented in the nineteenth and twentieth century. Although bibliographically-inclined users might wish for more information about these images, the books in which they appeared, and why, the illustrations and photographs at least give some sense of how Kilcolman Castle has been represented over nearly two centuries in print.

Figure 3: 3-D rendering of ground floor parlor of Kilcolman Castle. Although its animation lacks fine detail, it nonetheless offers a useful picture of domestic interiors from Spenser’s period.

In a manner much like John N. Wall’s Virtual Paul’s Cross project, which simulates audio recordings of John Donne’s sermons in a 3-D rendering of St. Paul’s Churchyard, the reconstruction of Spenser’s castle offers users four fly-through virtual tours. Although few in number and occasionally cartoonish in appearance, these short videos provide moving views through the outdoor Bawn Area and its enclosure, the Tower House and Spenser’s bedroom and study (here, a printed copy of The Faerie Queene’s second part lies open upon a desk), the Great Hall and the ground floor parlor (see figure 3), and the garden. The tours include no audio, but could in later versions. Designed not only for scholars but also for a general audience, these videos are accompanied by an Interactive Tour of ten areas in the compound. Here, users can click on objects in each tour to learn more about their function in Elizabethan domestic settings and any allusions to similar objects in Spenser’s poetry. The applications for in- or out-of-classroom instruction in Early Modern material culture are obvious here, and are appropriate at an undergraduate and possibly even a secondary level.

Although the objects populating the 3-D renderings of the castle have no factual basis, Herron emphasizes the pedagogical value of their speculative and imaginative presence. Barrels, lutes, harps, maps, desks, and military equipment all carry their own lessons about Spenser’s involvement in English and Irish literature and history, and Herron’s prose is both accessible and inviting, pointing in each case to “literary connections” and including a bibliography for the especially curious student. Indeed, the site’s infrastructure has been crafted to guide users through the interior of Spenser’s Irish dwelling toward its particular material objects and finally to his poetry (if not even further to current academic debates).

Clear about the purposes of its speculative and imaginative dimensions, and committed to a fuller and more comprehensive understanding of Spenser’s Irish settlement, Centering Spenser offers great potential for the future of Spenser Studies. With collaborators at ECU’s University Multimedia Center, Herron has positioned his project as a competent bridge between traditional research and digital scholarship, a repository for future investigations of Early Modern Ireland, and a suggestive teaching resource. It may have some wrinkles thus far in its linking structures, namely in the navigation from certain parts of the website to others, but this can be corrected easily enough, and the site map is a useful support in the meantime. Along with forthcoming efforts including David Lee Miller and Song Wang’s PARAGON, a software tool for intelligent collation among digitized printed materials from different repositories, we can expect Centering Spenser to find a stable place in relation to Spenser Online and eventually within the greater network REKn. Herron’s efforts are well-studied according to traditional methods and pedagogically worthwhile for today’s students. In its careful scholarship and methodological experimentation, this website stands as an exemplary model for future projects of this kind while remaining open to the possibility of development.

Andrew S. Keener

Northwestern University

44.2.34

Comments

You must log in to comment.