Organized by Joe Moshenska, Ayesha Ramachandran, and William N. West

Jump to…

1) William N. West, ‘Acts of Poetry’

2) David Lee Miller, reading The Faerie Queene I. Prol. 1

3) Adam Smyth, ‘Spenser and Cutting: “most happy letters fram’d by skilfull trade”’

4) Leah S. Veronese, ‘Reflection on reading Amoretti 20’

5) Jeff Dolven and Leah Whittington, ‘Spenser by Diagram’

6) David Landreth, reading The Faerie Queene III. 4. 16-18

7) Kat Addis, ‘Someone is Stuck in the Bower: A Performance of Lyric from Tasso to Spenser’

******************

William N. West

What does Spenser have to do with performance? Or what does performance have to do with Spenser? In 2017, at a conference co-organised by the International Spenser Society and Shakespeare’s Globe, actors Philip Bird, Dominic Brewer, Deirdre Mullins, musician Arngeir Hauksson, scholar-makers Linda Gregerson and Will Tosh, and me, devised one set of responses to these questions.[1] Working from passages of Spenser’s poetry suggested by members of the ISS, we offered an evening of enactments of scenes from Spenser’s poems, in the Globe’s recreated indoor theatre space, the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, as a Research in Action workshop. Five years later, at the urging of International Spenser Society president Ayesha Ramachandran and president-elect Joe Moshenska, a different group revisited the question in the 2022 MacLean Lecture, which reconfigured itself as a series of performances of Spenser’s poetry.

A MacLean Lecture, or as participants Jeff Dolven and Leah Whittington describe it below, ‘the MacLean-Lecture-cum-Spenser-circus’, offers very different affordances than trained actors on the stage of the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse. Most obviously, none of the participants in 2022 were actors, even if as teachers we are also performers. Instead of an audience gathered together in a candlelit space, we were distributed across continents and time zones, each in our own spaces, sharing the disembodying, depresencing, differently engaging and disorienting no-place of Zoom, which the past few years have afforded us plenty of time to contemplate and to rehearse the kinds of performance it requires and enables. How then, though, to perform Spenser thus? The first thing that occurred to us was again to solicit passages of Spenser, now to be read by the volunteers who chose them instead of passed to actors to play them. So we did, and they did, too: David Landreth, David Lee Miller, Leah S. Veronese, choosing and reading boldly, commitedly, revealingly, sometimes startlingly; all the passages as well as Leah’s reflections on her selection are included below. But we also wondered, what else might it mean to perform a part of poem than to give it a reading? What other forms of performance might be imagined for Spenser’s writing?

There are other arcs to performance that poems may invoke aside from being a script to be voiced or embodied. To perform, especially in the English of the sixteenth century, suggests carrying a process through to an endpoint, not just playing back something already fixed, but reaching it, or reaching toward it, across time.[2] Thinking more about the forms of performance brought out the form in performance, and other formations of poetry came suggestively forward. Performances of poems opened onto poetry per se as performance; into poetry as information, the giving of form to matter, and as informing, often with a greater sense of materiality in Spenser’s time than ours; poetry as and of reformation; as remediation, from one form to another; both poetry and performance as what Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann called deformance, contingent reworkings of a poem that have the potential to inform and reform it (an approach Adam Smyth takes up explicitly and brilliantly in his reflections below).[3] How else, or in what other ways, might a poem’s performance inform us?

Robyn Schiff’s long poem in progress, ‘Information Desk: An Epic’, represents the work of sorting, retrieving, and transporting that poetry does, corporealizing the information it records (or informing the corpora it represents):

There was a cart

we used to transport brochures in it

from a storage closet

to the Desk. You had to steer it

back through the Renaissance

into a passage that

opened in a dark medieval hallway

through a door without a handle

you backed into after opening

one-handed with a key called

the Number Two…[4]

The narrator’s tasks sound like those of Spenser’s Eumnestes, or maybe like Britomart waiting to open the door of Busirane’s house. But this could almost be an account of Spenser himself, backing through his Renaissance and steering into a medieval hallway which he searches one-handed. The poem proposes that ‘Information’ is not disembodied but mapped into the motions through which it is sought and found. In the poem information elicits action: it is moved and retrieved, it moves things and allocates them, it itself moves and retreats and sometimes advances. This passage – a passage of poetry, and its passages through hallways and doorways – dramatizes one way we return to our histories. It represents the return as more fleshed than imagined, as enacted and embodied, as actually moving physically rendered words through places that evoke past moments. It also stages the poem’s own organization into stanzas that translate the rooms through which we pass, seeking information, becoming informed, informing. Even calling this a passage recognizes, or acknowledges, or activates, in the ambiguous meaning of the word a locomotion more actual than we may usually understand in the phrase a passage of poetry.

But Schiff’s poetry does not just remember an allegorically-inflected performance of retrieval, it actually performs one. It is an example as well as a representation of poetry acting. ‘We used to transport’ hesitates between an instrumental sense for a cart (we used a cart to transport brochures) and an imperfect tense for transport (there was a cart, and we used to transport brochures). Transport is, of course, metaphor – like translation, it means metaphor, translates metaphor, and here it is metaphor, too, a metaphor for metaphor than brings things back from the dark room of the past. Schiff’s poem in-forms itself, and doing so it signals its own made quality, but also how it is made from what it is given, like Kat Addis’s reflection on her own performance of others’ words, ‘Someone is Stuck in the Bower’. Spenser – E.K., anyway – also insists that poetry is a making: ‘For in this word making, our olde Englishe Poetes were wont to comprehend all the skil of Poetrye’.[5] In Poetics, from which this observation comes, Aristotle contrasted this poetic making to doing, to drân or drama, relating them without fully distinguishing them (1447b, 1448b). Can there be a making without a doing, poetry without performance? Spenser’s poems, Schiff’s, Addis’s, Miller’s or Landreth’s or Veronese’s — maybe any poem, then — at times seems suspended between concretization and enactment, its form and its performance, between poiēma and poiēsis, poem and poetics. In this year’s MacLean Event, the speakers found their passages performing in diverging ways, alike discovering or inventing many kinds of making and doing: patterning, realizing, completing, initiating, plotting, and interpreting.

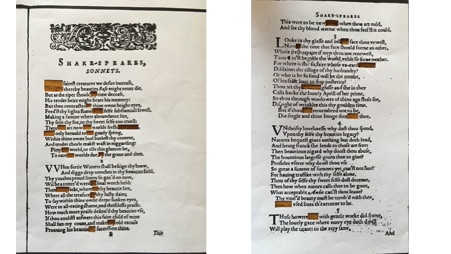

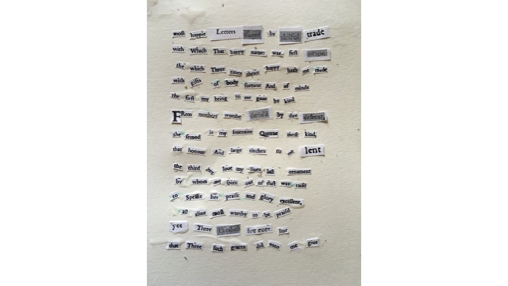

These performances electrified. Adam Smyth recomposed one of Spenser’s sonnets by cutting out and reassembling matching words from one Shakespeare’s, which yields the same sonnet, so to speak, but shot through or perhaps deeply tagged with the senses of the words in their locations in Shakespeare’s poems. Jeff Dolven and Leah Whittington asked attendees to diagram a stanza randomly chosen from The Faerie Queene, converting its verbal rhythms and patterns into visual analogues. Kat Addis presented a series of poems that bridged the distance between a passage in Tasso and Spenser’s translation of it, embedded in The Faerie Queene. David Lee Miller, David Landreth, and Leah S. Veronese offered more conventional readings of passages, but in the expanded context that the other deformances opened up, their readings sounded differently, like Spenser’s sonnet remade with Shakespeare’s words or Addis’s with Tasso’s. They weren’t just readings of stanzas, but choices to read rather than to do something else with stanzas. Leah Veronese’s reflection emphasises the choices that a reading always involves, including the recognition that there can be a choice to suspend rather than determine, and that no iteration gets the last word in any case. A poem is always a response, and in these performances we saw how any poem also always proposes an opportunity for another one. Another one at least.

******************

David Lee Miller, reading The Faeerie Queene I, Prol. 1

Yo! I the man, whose Muse whilome did maske,

As time her taught, in lowly Shepheards weeds,

Am now enforst a far vnfitter taske,

For trumpets sterne to chaunge mine Oaten reeds,

And sing of Knights and Ladies gentle deeds;

Whose prayses hauing slept in silence long,

Me, all too meane, the sacred Muse areeds

To blazon broad emongst her learned throng:

Fierce warres and faithfull loues shall moralize my song.

******************

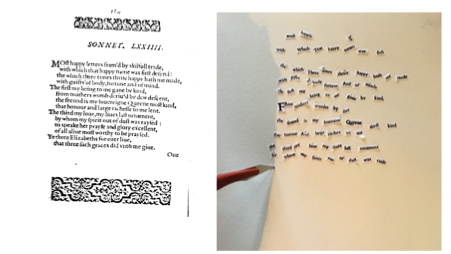

Spenser and Cutting: ‘most happy letters fram’d by skilfull trade’

Adam Smyth

I have been interested for some time in the ways early modern readers cut up their texts, not as a way of condemning or censoring, but as a form of reading, a way of responding and processing the material. One spectacular instance of this culture of knives and scissors was the Anglican religious community of Little Gidding, where in the 1630s and 1640s, the extended family of Nicholas Ferrar produced lavish folio Biblical Harmonies, constructed out of cut-up printed Bibles. Ferrar’s nieces, Anna and Mary Collett, obtained copies of the Gospels which they anatomised with scissors – often on a word-by-word level – reorganised, and glued under 150 chapter headings, describing Christ’s life, with hundreds of snipped-out images supplementing the text. The purpose of each Harmony was to present a narrative that revealed but then reconciled ‘agreements & differences’ (as one title-page put it) between gospel accounts.[6]

Little Gidding’s slicing and patching looks anomalous, and has often been described in terms of a strange exceptionalism, but in fact it was only a dramatic enactment of a wider culture of cutting. We see evidence of this both in the instructions books provide for their own consumption, and in the tattered remains left by obliging readers – as when, for instance, John White’s Briefe and easie almanack for this yeare (1650) tells readers to cut out ‘the whole kalender’ for 1650 for use elsewhere: ‘which being cut out, is fit to be placed into any book of accompts, table book, or other.’[7] An enactment of this prescription survives in the Folger Shakespeare Library: White’s 1650 almanac, along with another from 1656, has been cut out and glued into a manuscript notebook, which in turn contains within it A manual for A justice of peace his Vade-mecum (1641).[8]

What can we learn if we adopt cutting as an uninhibited critical mode – if we relax our sense of taboo or transgression and cut up early modern texts today? What can we observe about texts that we might not otherwise perceive, when we have as our tool not pen or pencil or tablet or laptop, but knife, scissors, and glue?

In order to think this through, I conducted a little experiment. I wondered what would happen if I tried to patch together an Edmund Spenser poem using Shakespeare’s words: if, in other words, I cut out words from Shakespeare’s Sonnets, published in print by Thomas Thorpe in 1609, and used these to recompose a Spenser sonnet, published in print by William Ponsonby in 1595. The poem I chose was sonnet 74 from Amoretti, a poem normally understood to describe Spenser’s love for three Elizabeths: his mother, Queen Elizabeth I, and his second wife Elizabeth Boyle. I selected it primarily because its first line hinted at my method (‘most happy letters fram’d by skilfull trade’).

I used the full text database www.opensourceshakespeare.org to find where, in Shakespeare’s sonnets, each of the words in this poem appeared, and annotated the whole poem with markers of place.[9] Here, for example, is my annotated version of Spenser’s final line, with a note of where each word appears in the 1609 Shakespeare sonnet sequence, with sonnet number followed by line number:

that [5.1] three [104.7] such [9.14] graces [17.6] did [31.11] unto [47.2] me [49.6] give [51.14]

Thus Spenser’s word ‘that’ appears in Shakespeare’s sonnet 5, line 1 – and so on. (Of course, the word ‘that’ appears in other sonnets, too, and in such an instance of multiple possibilities I simply picked one.) And here, as a kind of translation, is all of Spenser’s sonnet 74 converted into word location markers in Shakespeare’s sonnets and other writing, where [x.y] = sonnet x, line y:

[10.4] [16.5] [Pericles 3.0] [King Lear 4.6] [1.3] [Rape of Lucrece 1419] [Pericles 4.2],

[1.6] [4.14] [1.2] [8.11] [36.12] [5.12] [20.9] [Hamlet 1.1]:

[1.3] [5.4] [104.3] [6.8] [56.14] [25.13] [9.11] [20.11] [2.13],

[3.14] [103.12] [2.4] [24.3], [14.5] [1.10] [2.6] [9.8].

[1.10] [20.9] [2.11] [2.5] [1.5] [22.1] [11.11] [1.14] [10.11],

[1.1] [3.9] [3.5] [Midsummer Night’s Dream 1.1] [2.12] [31.12] [Richard II 1.1],

[3.1] [59.4] [3.2] [10.9] [33.2] [96.5] [15.10] [10.12],

[1.9] [13.10] [13.4] [44.10] [87.6] [87.10] [88.1] [Pericles 1.0].

[1.14] [99.10] [100.9] [9.13], [102.6] [45.9] [67.14] [1.9],

[8.10] [11.9] [13.13] [56.8] [55.6] [57.2] [108.10] [109.1] [150.13]:

[150.2] [53.9] [85.1] [85.2] [89.3] [91.1] [38.3],

[39.2] [2.5] [17.13] [19.8] [26.12] [27.1] [32.6] [85.9].

[All’s Well That Ends Well 4.3] [104.4] [Henry VIII 5.5] [Pericles 3.2] [3.13],

[5.1] [104.7] [9.14] [17.6] [31.11] [47.2] [49.6] [51.14].

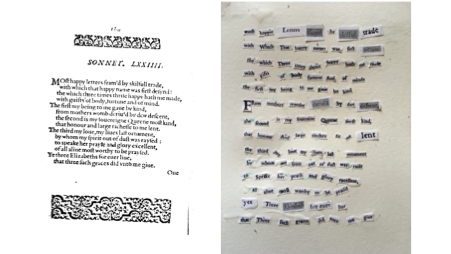

This gave me a map for finding Spenser’s words in Shakespeare’s sonnets. I printed out an EEBO text of the 1609 sonnets, and located, and then cut out, each word, one by one, working through Spenser’s poem in a strange, slow, version of reading, gluing the words onto a page.

Spenser’s poem gradually began to pull itself together out of these cut-out words from 1609, as you can see here.

And eventually, I had the whole poem: part ransom note, part 1630s Little Gidding Harmony, part Sex Pistols album cover – but all of Spenser’s poem, made from Shakespeare’s words.

I also had a by-product which I hadn’t thought about at the outset: the tattered version of my print out of Shakespeare’s sonnets, with holes where I’d cut out Spenser’s words.

This as an accidental erasure poem, or Shakespeare redacted. Here are these cut pages from the back, looking like a tower block at night.

There is a lot to say about this, both as process and product, and as an instance of ‘deformance’ as described by Lisa Samuel and Jerome McGann – an interpretative method whereby the text itself is altered, and something new is understood or released as a result.[10]

I’ll briefly draw out a few points that struck me as I was doing this.

All but 11 words in Spenser’s sonnet appear in Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence. You can see the 11 words that don’t appear in Shakespeare’s sonnets here, in underlined bold.

Most happy letters, fram’d by skilful trade,

With which that happy name was first design’d:

The which three times thrice happy hath me made,

With gifts of body, fortune, and of mind.

The first my being to me gave by kind,

From mother’s womb deriv’d by due descent,

The second is my sovereign Queen most kind,

That honour and large richesse to me lent.

The third my love, my life’s last ornament,

By whom my spirit out of dust was raised:

To speak her praise and glory excellent,

Of all alive most worthy to be praised.

Ye three Elizabeths forever live,

That three such graces did unto me give.

When I couldn’t find these 11 words in Shakespeare’s sonnets, I turned to his other writings, and cut these out to use. The words came from Pericles, King Lear, The Rape of Lucrece, Hamlet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Richard II, All’s Well That Ends Well, and Henry VIII.

These anomalies are interesting: it’s surprising that Shakespeare’s sonnets don’t include the words ‘skilful’, or ‘trade’, or ‘forever’, or – almost unbelievably – ‘letters’ (a word that is everywhere in the plays.) This is the kind of negative research question that’s usually hard to formulate – what words does Shakespeare not use? – but cutting brought this into the light. Only one word in Spenser’s poem was nowhere in Shakespeare’s entire canon: the plural ‘Elizabeths.’ (I used ‘Elizabeth’ from Henry VIII to stand in for the plural, and also to mark out the absence.)

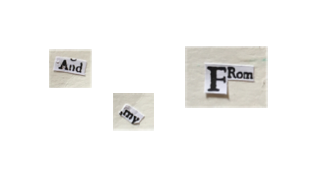

The locating, cutting, placement, and gluing, was a slow and fiddly process that couldn’t be hurried. It was far slower than the most lingering version of conventional reading. As I cut, I came to think of words in different ways. Some of these thoughts were very practical. I was worried that the little papery words would blow away – as they nearly did, at one point, when wind blew in through the window, as you can see here.

I became aware of words as visual units, as pieces, rather than semantic content. I started to notice that there were shorter words inside longer words: that the word ‘ornament’, for example, has the word ‘name’ in the middle.

The cut out words, glued down on the page, sometimes carried with them evidence of their original contexts: glimpses of letters that were previously adjacent, or shifts in type (the capitalised F and R in ‘from’) that signalled something about the word’s original position.

There was a strong sense of these words, as they constitute Spenser’s poem, recalling their origins, and once I felt that, I began to wonder whether these words brought with them, into Spenser’s poem, some of their original connotations. The word ‘derived’, in line 6 – ‘From mother’s wombe deriv’d by due descent’ – comes in my cut-out version from the opening scene of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where Lysander defends the status of his genealogy to Theseus: ‘I am, my lord, as well derived as he’. Is this scene, or a trace of this scene, pulled into the poem?

Even if we don’t know the precise origin of these words – and I’m thinking of origin here not as etymology but as placement on the page – the sense that these words come from elsewhere is worth thinking about. Despite our preoccupation with literary authorship as individual expression, and as uniqueness of voice, we need to remember that writers in English work with a small pool of 26 letters that is the common property of everyone. Patching together Spenser’s poem is a reminder not only that books are inevitably intertextual – they grow out of other texts – but more fundamentally that all writing involves selecting words from a finite pool. Some technologies, like the typewriter, make this sense of writing as selection vividly apparent: writers may create an infinite number of worlds, but the next action can never be more than choosing one from a small number of keys. The pen and the blank page create the illusion of creativity ex nihilo: but searching, cutting, pasting, helps us understand writing as the act of choosing pieces from a constrained group of words.

******************

Leah S. Veronese

When choosing a sonnet from Spenser’s Amoretti to read aloud there was no doubt in my mind that I would read Sonnet XX:

In vaine I seeke and sew to her for grace,

and doe myne humbled hart before her poure:

the whiles her foot she in my necke doth place,

and tread my life downe in the lowly floure.

And yet the Lyon that is Lord of power,

and reigneth over euery beast in field:

in his most pride disdeigneth to deuoure

the silly lambe that to his might doth yield.

But she more cruell and more saluage wylde,

then either Lyon or the Lyonesse:

shames not to be with guiltlesse bloud defylde,

but taketh glory in her cruelnesse.

Fayrer then fayrest let none euer say,

that ye were blooded in a yeelded pray.

First, the hyperbolic imagery of a tyrannical leonine mistress merrily embarking on a bloody rampage makes it an ideal candidate for a dramatic reading – as does the power of its closing couplet: ‘let none euer say,/ That ye were blooded in a yeelded pray’.[11] It also felt like a fitting choice as the sonnet inspired the title of my DPhil thesis Suing for Grace: the Early Modern Rhetoric of Petition. I have spent many an hour considering its astonishing and disorientating entangling of courtly, spiritual and martial petition. Finally, I had in fact performed the sonnet before, during the 2020 lockdown, as part of King’s College London’s Sonnet-A-Day online series, bathetically cutting its closing couplet by accident – to the rather abrupt ‘That ye were blooded’ – in a misadventure with video-editing. High time for a redemptive reprise performance.

Neither theatrical metaphor, nor the concept of sonnets as performances, are unfamiliar either in the imagery of early modern sonnets themselves, or the meta-language of sonnet criticism. The Amoretti’s mistress wryly reduces the speaker’s Petrarchan exertions to stale performance: ‘But when I pleade, she bids me play my part’ (Sonnet XVIII, l.9). Spenser’s own theatrical conceit in Sonnet LIIII (‘Of this worlds Theatre in which we stay’) is at the heart of Louis Martz’s formative re-reading of the Amoretti’s violent imagery as playful Petrarchan pastiche: this sonnet indicates the complete recognition of the lover that he is deliberately playing many parts, staging ‘all the pageants’ in an ancient festival of courtship, adopting all the masks that may catch his lady’s eye and prove his devotion.[12] Elizabeth Biemann likewise took Sonnet LIIII’s image of ‘Sometimes I … mask in myrth like to comedy’ as the title of her defence of the ‘witty intricacies’ of the sequence.[13] In a more critical mode, Thomas Roche Jr used Nashe’s theatrical image of Astrophil and Stella as a ‘paper stage’ on which ‘the tragicommody of loue is performed by starlight’ as a prompt to interrogate Astrophil and the moral lessons of the sequence: ‘But to the Elizabethans who firmly believed that ‘all the world’s a stage’, the pleasures of such theatres lay in their imitation of nature to teach true morality…; what kind of morality does Astrophil’s despair teach?’[14] The sonnet as performance was therefore used in the late twentieth century to defend the Amoretti by arguing for witty Petrarchan play-acting, but also in the case of Astrophil and Stella to question the reliability of Sidney’s speaker.

Although critically reading the sonnet as performance is a familiar practice, literally performing a performance is a curious exercise. I, and many others, read the speaker of Amoretti as a decidedly unreliable narrator. It is therefore strange to suddenly inhabit and voice his first-person perspective. Whereas in critical reading you can pivot between the speaker’s narrative and Spenser’s suggestions of his flaws, by reading aloud I didn’t want to imbue the speaker too much credibility. This felt like the danger of a “straight” reading: performing the complaint of the speaker with emotional seriousness, and out of the context of the sequence, seems in some way to be complicit with his representation of his mistress’s cruelty. An obvious response to this problem would be to counter his distortion by reading with an ironic undermining tone - inviting scepticism. When considering how to read aloud the sonnet, however, it became clear just how difficult a poem it is to perform tongue-in-cheek. There is certainly comic potential in a seemingly Mercilla-like regal mistress in one line receiving a suitor in the next line by stamping on his neck - more like a triumphant Radigund:

In vaine I seeke and sew to her for grace,

and doe myne humbled hart before her poure:

the whiles her foot she in my necke doth place,

and tread my life downe in the lowly floure. (ll.1-4)

The crucial ‘the whiles’ further creates the cartoonish image of the speaker attempting to petition whilst already squished under foot. Nevertheless, the hyperbolic leonine metaphor which made the sonnet so inviting to read, brings with it images which do not roll off the tongue playfully with tremendous ease: ‘with guiltlesse blood defylde’. Even in this first quatrain ‘tread my life downe’ is shockingly comprehensive in its oppression. Although ‘my life’ suggests the risk of being physically crushed, it also further suggests the detrimental effect of such submission.

These problems for performance are revealing in terms of tone. For me, this exercise neatly underlines the limits of the Martzian strategy of reading the sonnet as a playful performance of Petrarchan suffering. Even Martz himself conceded that ‘the tone’ of the similarly violent Sonnet XIII ‘is very hard to describe. It would be too much to call it parody, and yet the postures seem to be deliberately judged by the presence of some degree of smiling.’[15] To take this as a stage direction for performance, the same disturbing images in Sonnet XX which halted a slightly sarcastic rendition of the poem would also surely be stumbling blocks for a slightly ‘smiling’ rendition. It might even seem borderline sociopathic. James Fleming, reading the sonnet and the sequence from a colonial perspective ‘haunted’ by the Smerwick massacre, expresses a frustration with the Martzian model of deflecting from the violence of the sequence by arguing for its humour.[16] Realizing Martz’s theatrical metaphor further highlights how the violence of the Amoretti cannot be successfully smiled away. This in turn demonstrates what we can reveal and learn through performing poetry.

******************

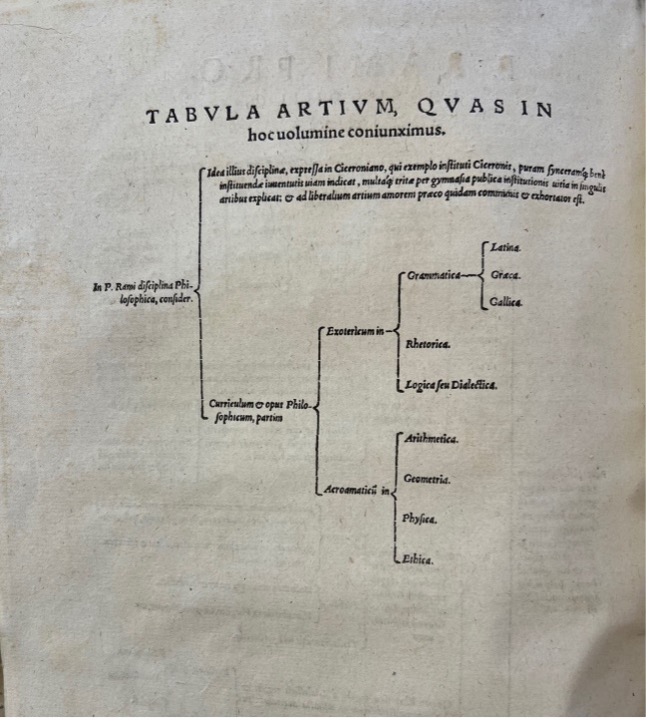

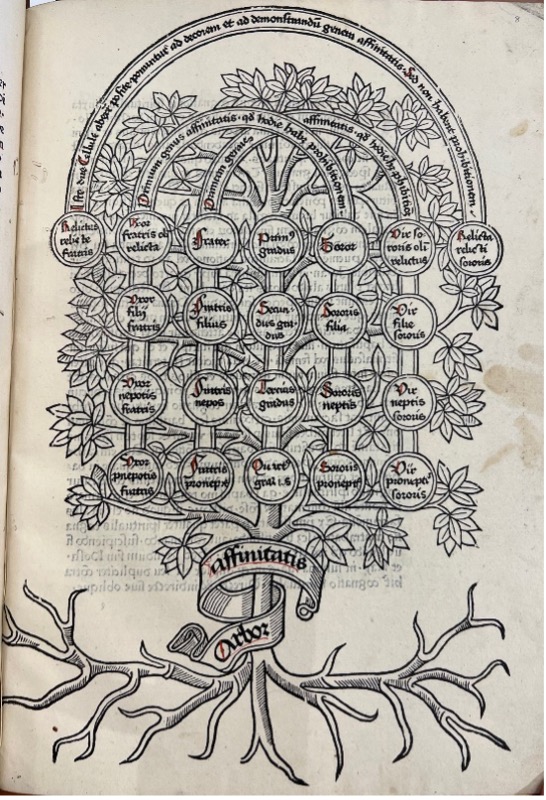

Jeff Dolven and Leah Whittington

Erasmus was of the opinion that the best way to understand a text is to imitate it. Petrus Ramus, later in the sixteenth-century, made a different recommendation: the way to understand a text is to make a diagram, dividing its elements, mostly in two, until they can be divided no more; what is left is a hierarchical taxonomy laid out on the page as a branching tree, rooted at the left margin and ramifying toward the right. For Walter Ong, looking back from the vantage of the then-young Information Age, the transition from Erasmus to Ramus marked ‘a movement away from a concept of knowledge as it had been enveloped in disputation and teaching … toward a concept of knowledge which associated it with a silent object world, conceived in visualist, diagrammatic terms’.[17] Imitation is loyal to the idiom and the medium it imitates. A diagram can depart from both, and offers its schematic reduction and visual transposition as new study-matter for the curious intelligence.

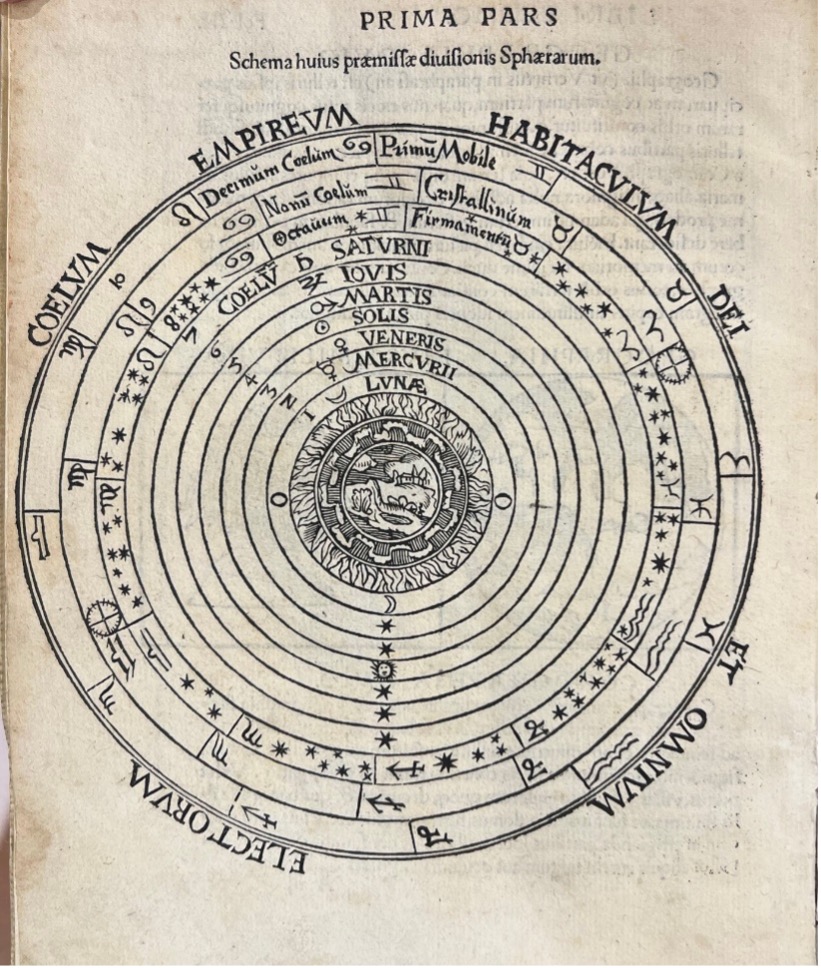

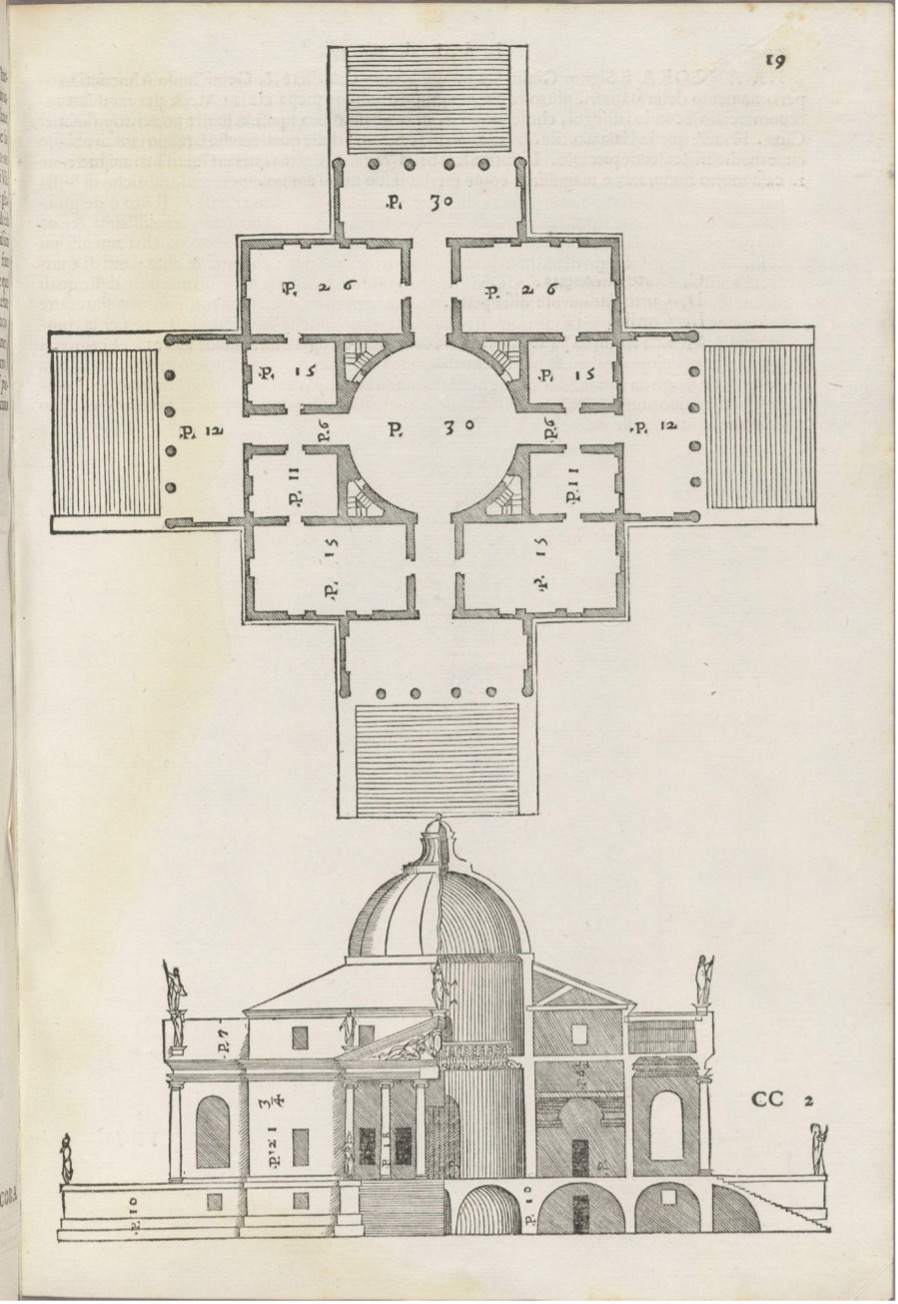

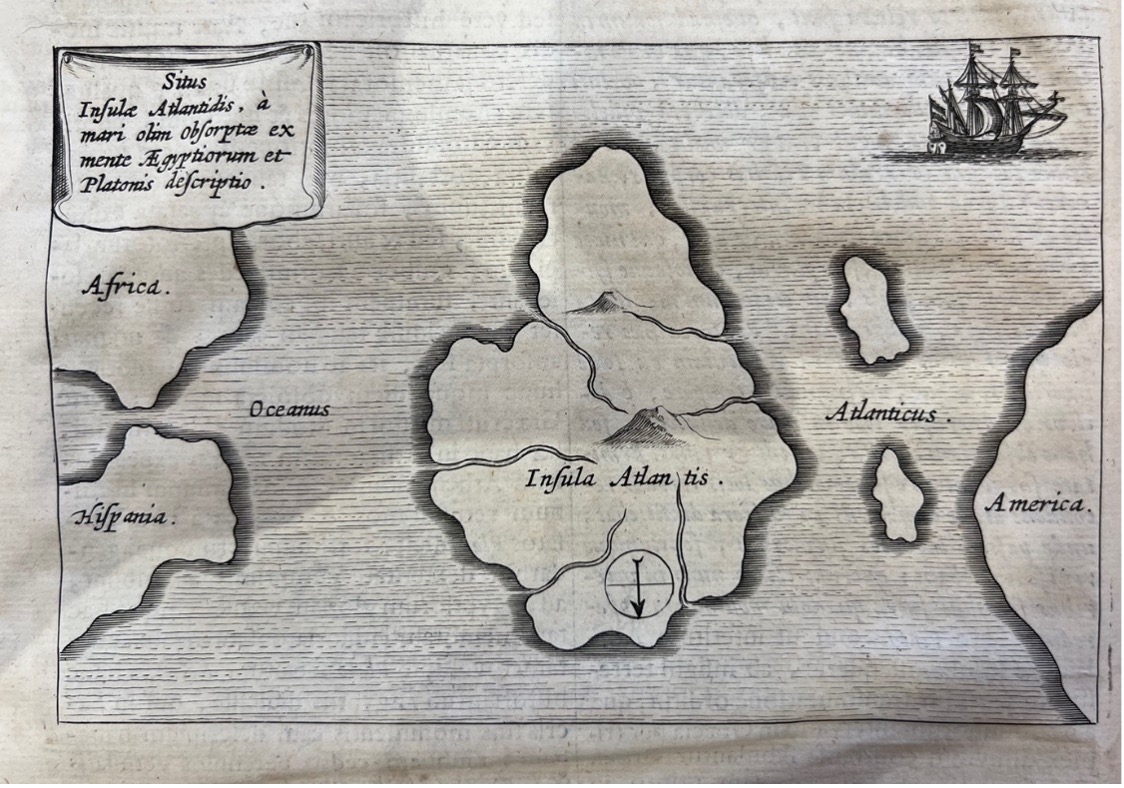

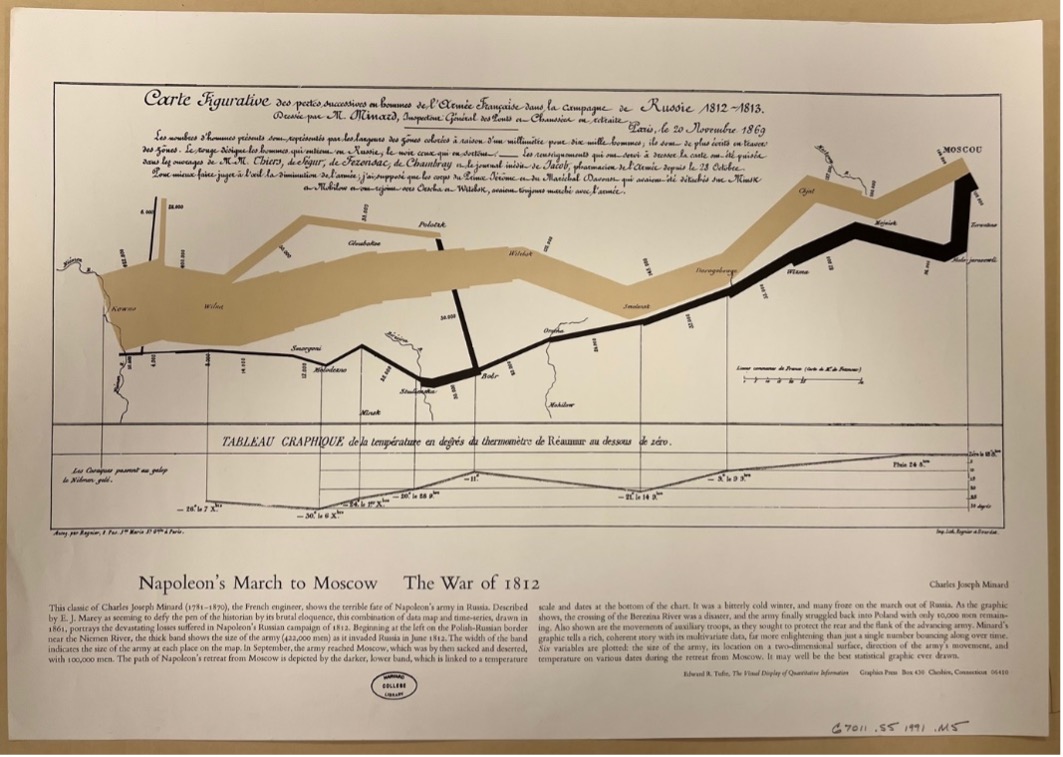

That is exactly what we set out to offer the gathered Spenserians at this year’s MacLean-Lecture-cum-Spenser-circus. The charge to the audience over our fifteen minutes was simple: make a diagram of a randomly chosen Spenserian stanza. Beyond that, we dared not insist because figuring out what kind of diagram to make – and what to diagram – was part of the thinking we wanted to elicit from the assembled troupe. We did offer some examples, though, to stimulate the diagrammatic imagination. Ramist tables were among them:[18]

But we proposed others, too, including different trees:[19]

concentric, cosmological “eggs”;[20]

architectural plans;[21]

fantastical maps;[22]

and even Charles-Joseph Minard’s famous diagram of Napoleon’s Russian campaign, with a fat line marching to Moscow, a dwindling line struggling back again through the snow.[23]

Some of our examples were what historian of science Peter Galison calls ‘homomorphic’, borrowing elements of form from their topic; others, ‘homologic’, expressing abstract relations among concepts.[24] We wanted to inject into the exercise Ramus’s spirit of independence, but not his purism, and to offer up the diagram as an emphatically mixed mode, with opportunities for measurement, for picture making, for fields and timelines and flow charts and more.

The fun began at a little after noon with a spin on the wheel of fortune à la Spenser@Random. The Google Number generator produced its set of numbers, directing us to the destined book, canto, and stanza: 3-6-46. After some flipping of pages and scrolling of screens, we found ourselves face to face with The Faerie Queene’s mythopoetic core. As we read the stanza aloud, mirth and consternation ensued: was it really possible that we’d be diagramming … the Garden of Adonis? Of all the allegorical temples of the poem, the most thematically integral to the generation of forms? Was the game was rigged? Should we spin again? No, we decided, our job was to follow the numbers, attend to the poem, and draw our diagrams. The stanza unfurled before us all its peril and luxuriance:

There wont fayre Venus often to enioy

Her deare Adonis ioyous company,

And reape sweet pleasure of the wanton boy:

There yet, some say, in secret he does ly

Lapped in flowers and pretious spycery

By her hid from the world, and from the skill

Of the Stygian Gods, which do her love envy;

But she her self, when ever that she will,

Possesseth him, and of his sweetness takes her fill. (Faerie Queene, 3.6.46)

Five minutes of diagramming, another five of zoom-sharing, and we were done, but seven brave Spenserians sent their diagrams to us after by email. Their range gives a good sense of what is possible in the exercise, and may suggest, we hope, further applications.

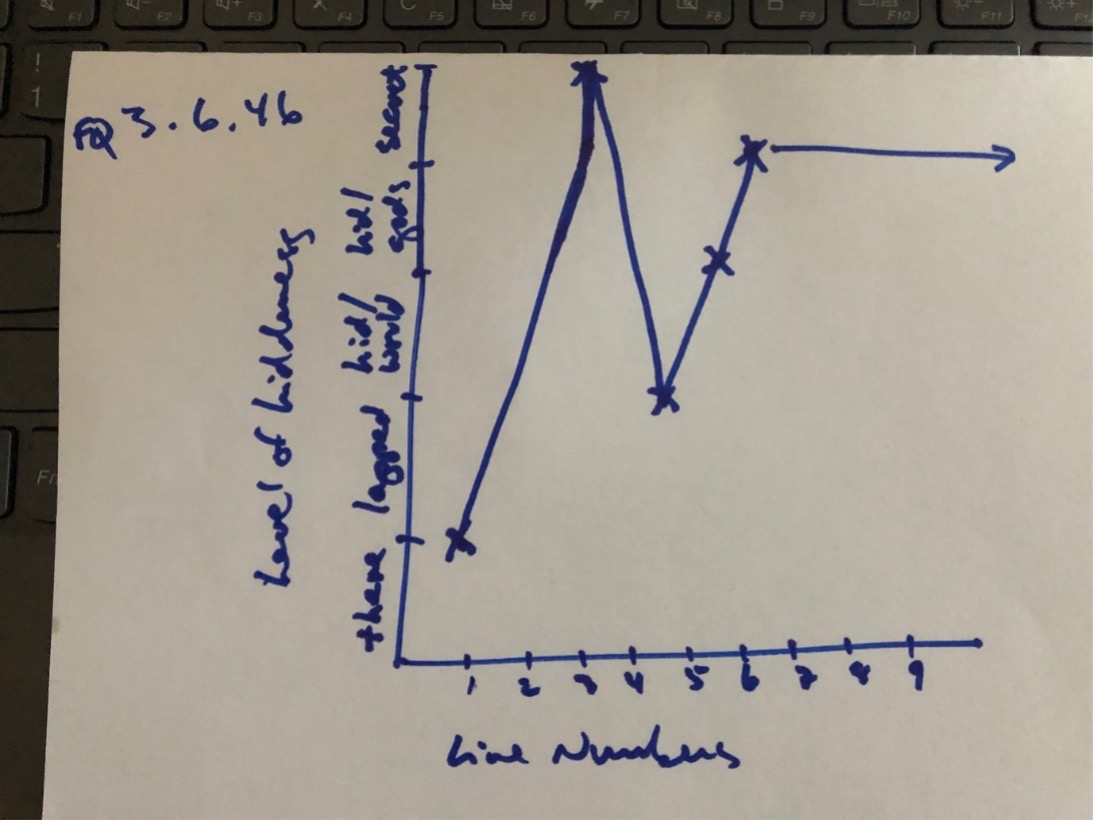

Chris Barrett gives us a Cartesian graph, with line numbers along the x axis, conventionally enough, but along the y axis, ‘level of hiddenness’.

The result is a snapshot of the stanza’s candour, beginning with the open facts; bringing us suddenly, with the third line, into a scene of intimacy; relaxing to gossip; and finally lapping the vision in flowers, protected from the gods and the reader alike. Time is vital: left to right, the graph-line makes vivid the stanza’s peek-a-boo.

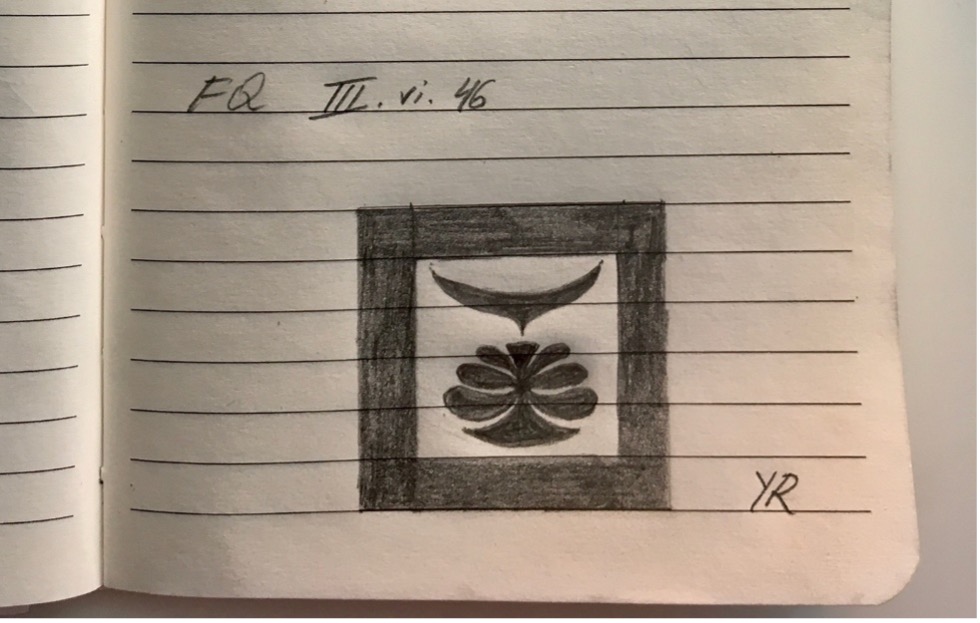

Yulia Ryzhik designs a letterpress ornament, perhaps soon to adorn the pages of a limited edition Faerie Queene. Linocut, she thinks, is the best technique for printing the device:

And fittingly, too: the simple lines and natural forms of the composition recall Matisse’s experiments with linoleum printmaking, and his later cut-outs seem to lie somewhere behind the lobed floral motif of Adonis ‘lapped in flowers’. But Venus is ascendant here, her wings stretched dovelike over her beloved, hovering between Holy Spirit and bird of prey. She and Adonis are not hidden from the Stygian gods but surrounded by them, a new take on the Garden’s eternal mutability: is death for Spenser a hostile perimeter or merely a decorative frame?

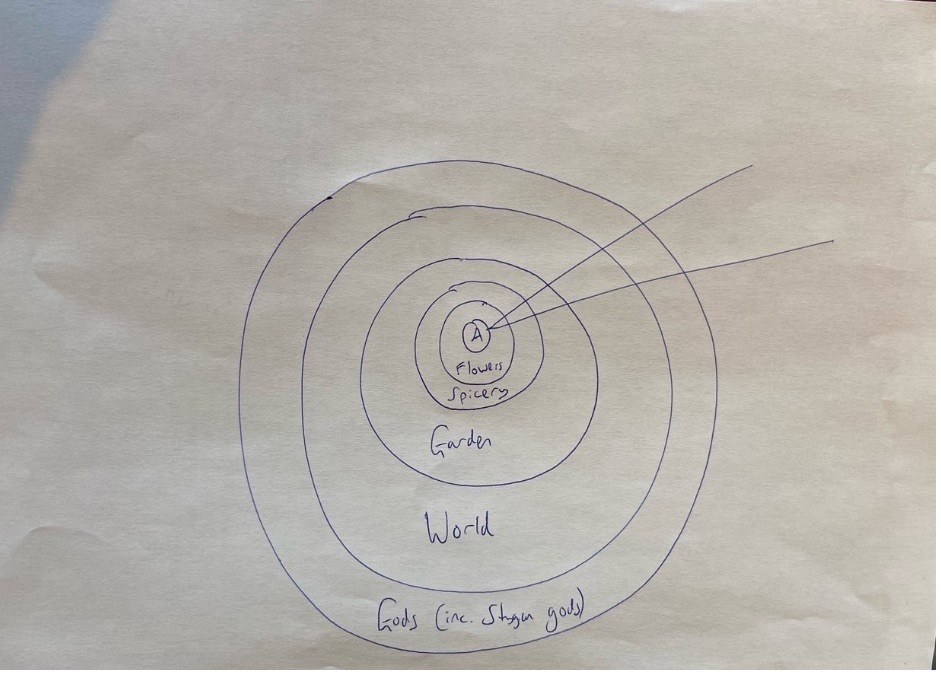

Joe Moshenska offers up one of those cosmological eggs, which is at the same time an archer’s target: Adonis is the bull’s eye, and the rings of abstraction, from the flowers to the remote gods, attenuate outward from his body.

‘The V is Venus’, he explains, ‘wedged into and across the static spheres like the point of a javelin, freely able to traverse these levels of being “when euer that she will”’. It is at once a map and a gesture, Venus’s swift prerogative slashing across its concentric concepts.

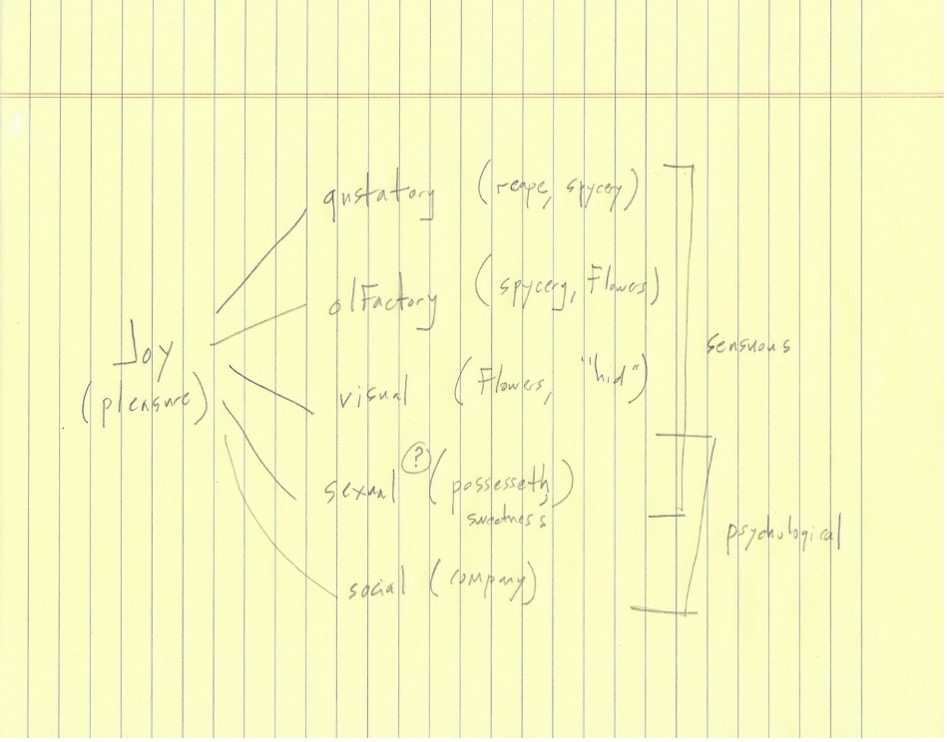

Joe Ortiz performs something like a Ramist analysis, choosing joy as his governing term.

It has five causes, branching to the right: taste, smell, and sight; also sexual desire and sociability. Where it gets really interesting is in the division implied between the two levels, sensuous (the first three) and psychological (the last two). We are prompted to recognise the way the stanza balances Venus’s almost autoerotic appetite, and the stubborn presence of Adonis as another body and another mind, who might keep her company.

Ken Gross produces two diagrams that show just how slippery the distinction can be between ‘homomorphic’ and ‘homologic’:

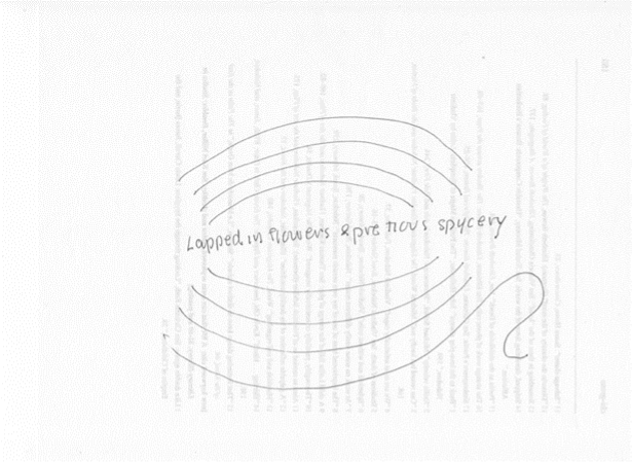

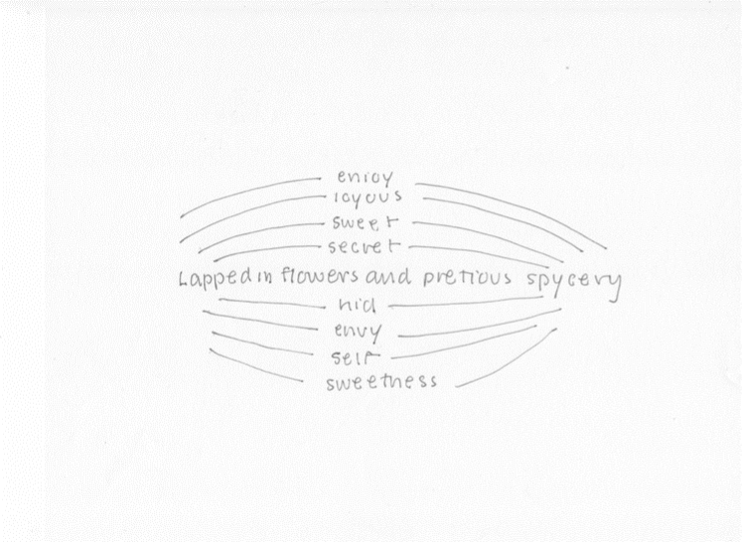

These schemas are both: they document the stanza’s physical shape on the page as well as suggesting logical relations among its parts. So, the fifth line, the spatial midpoint of Spenser’s 9-line stanza, appears in the middle of both designs, surrounded by curved marks above and below denoting the stanza’s other 8 verses: voilà, homomorphism. At the same time, Ken singles out that ‘central’ fifth line as more important than the others by writing it out in script, and, in the second drawing, gives the same homologic treatment to the keywords of each line. And what’s that long flowing tail on the first drawing’s alexandrine? Does it denote spatial or acoustic length? Or a festive flourish? Let’s go with c), all of the above.

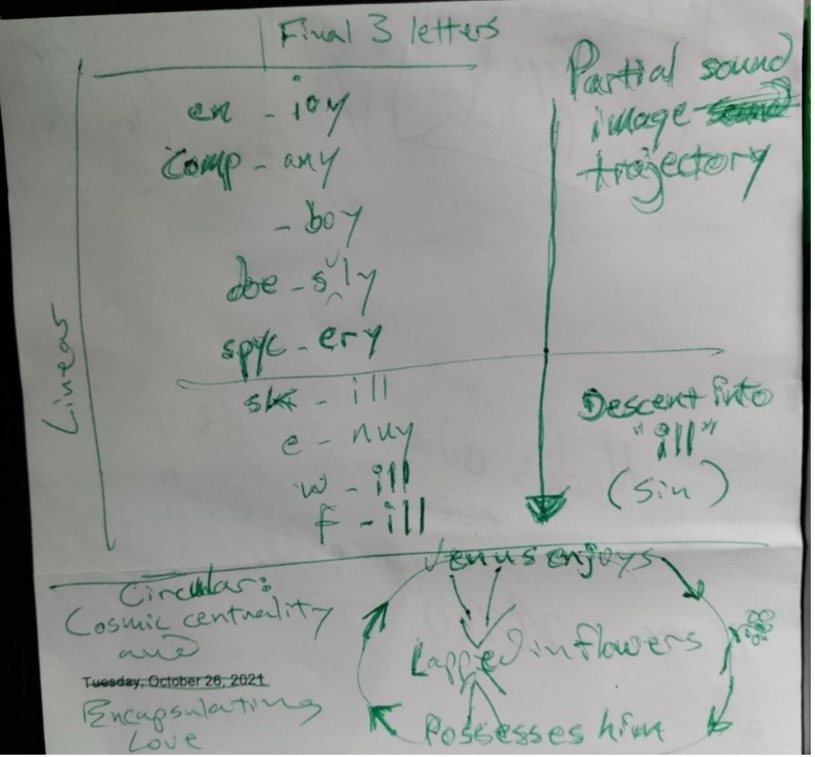

Thomas Herron discovers a ‘downward narrative trajectory’ in the stanza by designing a graph to chart the sounds of the last three letters of each line.

The graph moves from top to bottom, like a sideways bar chart, showing a gradual increase in ominous sounds from the cheerful ‘ioy’ of line 1 to the circumspect ‘ery’ of line 5 to the perilous ‘ill’ of line 9. This picture of the stanza as a sonic descent into moral hazard contrasts strikingly, he notes, with the circular, cosmic-type diagram of Venus with her flower Adonis at its centre. This stanza is two-faced, affirming and threatening at once.

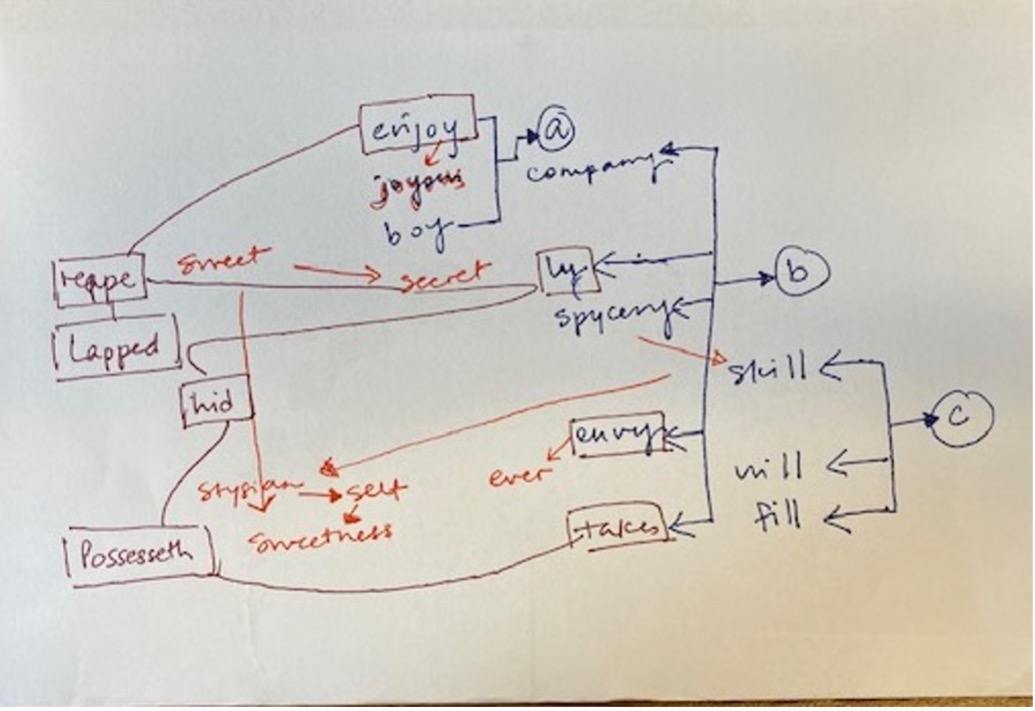

Ayesha Ramachandran’s diagram is perhaps the most syncretic.

It begins (it seems to ask us to imagine an order of its making?) by arranging the a-, b-, and c-rhymes in blue, on the right, and then traces a tangle of their sonic and semantic associations in red. So, to follow one path, ‘reape’ recalls ‘enjoy’ in sense, but its long e sound links it to ‘sweet’ and ‘secret’, which in turn evoke the -y of the b-rhymes. Meanwhile the p brings us to ‘lapped’, and that -ed gives us ‘hid’, and so on – a striking picture of how interdependent the poem’s forms of association are.

It should be clear from these examples that it is not only the kind of diagram that varies so widely, but also what participants decided could be diagrammed, everything from rhetoric to sound to affect to geography. So many questions subtend from each. Is this schema portable? Would it illuminate another stanza, or define a kind? Or is it particular to its occasion? Is it a record of a reading? A plan for making? The work of criticism? All these possibilities only reinforce the diagram’s potential as an engine of invention, whether for the student looking for some fix on the winding rhetoric of The Faerie Queene, or the scholar looking to see something familiar for the first time. Happy diagramming!

******************

David Landreth, reading The Faerie Queene III. 4. 16-18

Britomart skewers a strange knight:

The wicked steele through his left side did glaunce;

Him so transfixed she before her bore

Beyond his croupe, the length of all her launce,

Till sadly soucing on the sandie shore,

He tombled on an heape, and wallowd in his gore.

Like as the sacred Oxe, that carelesse stands,

With gilden hornes, and flowry girlonds crownd,

Proud of his dying honor and deare bands,

Whiles th’altars fume with frankincense arownd,

All suddenly with mortall stroke astownd,

Doth groueling fall, and with his streaming gore

Distaines the pillours, and the holy grownd,

And the faire flowres, that decked him afore:

So fell proud Marinell vpon the pretious shore.

The martiall Mayd stayd not him to lament,

But forward rode, and kept her readie way

Along the strond, which as she ouer-went,

She saw bestrowed all with rich aray

Of pearles and pretious stones of great assay,

And all the grauell mixt with golden owre;

Whereat she wondred much, but would not stay

For gold, or perles, or pretious stones an howre,

But them despised all; for all was in her powre.

******************

Someone is Stuck in the Bower: A Performance of Lyric from Tasso to Spenser

Kat Addis

Rósa, any kind of Rose, Acquarósa, Rose-water. Also a rowell of a spurre. Also the name of a certaine blazing Starre. Used also for any natural spot or moule upon a mans or womans skin.[25]

In canto 16 of Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata, at the centre of the sorceress Armida’s enchanted garden, a bird sings a two-stanza lyric encouraging lovers to seize the day:

“Deh mira” egli canto “spuntar la rosa

dal verde suo modesta e verginella,

che mezzo aperta ancora e mezzo ascosa,

quanto si mostra men, tanto è più bella.

Ecco poi nudo il sen già baldanzosa

dispiega; ecco poi langue e non par quella,

quella non par che desiata inanti

fu da mille donzelle e mille amanti.

Così trapassa al trapassar d’un giorno

de la vita mortale il fiore e’l verde;

né perché facia indietro april ritorno,

si rionfiora ella mai, né si rinverde.

Cogliam la rosa in su ‘l mattino adorno

di questo dì, che tosto il seren perde;

cogliam d’amor la rosa: amiamo or quando

esser si puote riamato amando.”

(Torquato Tasso, Gerusalemme Liberata, 16.14-15)

In Book 2 of The Faerie Queene, in Acrasia’s Bower of Bliss, somebody reprises that song in a close translation of Tasso’s lyric. My performance for the MacLean panel was an attempt to explore what it would mean to get stuck between these two lyrics, lost in translation between reading and writing, loving and being loved, seizing the day and failing to do so. Renaissance lyric poets seem, even more than most poets, to inhabit a looping kind of temporality in which their poems have always already been written by somebody else. I take this to be the ‘joke,’ if I may call it that, of Spenser’s replacement of Tasso’s bird with a ‘some one’ who ‘did chaunt this lovely lay’ (II.xii.74). That vague ‘some one’ is an endlessly recurring subject or, to draw on Patricia Parker’s insight, an eternally ‘suspended instrument.’[26]

“Hey, look” (this one sang) “I’ve hidden the verse

that brings out the rose

in her green shame unknown.

The door ajar,

a crack of light more beautiful.

Look here! The rude and buxom breast already

looking back hard and long!

close the door bold girl!

bold girl, close the door!

the man lusts after a thousand

gamine unique girls.

He alone will be a thousand lovers.

So bashed in, in a lived day

the forgotten green.

April cannot look her in the face.

She will never flower again.

Never be green again.

The rose gathers itself in the morning,

adorns itself with the day,

loses its cool in the evening,

and exchanges itself for love!

I am fascinated by the process of translation that ‘some one’ undertakes, and I wanted to elongate it in performance, extending its ability to produce whole poems as metaphors for one another. I am also fascinated by error, misunderstanding, and willfulness as they enter into translation and create spaces for ‘some one’s’ own thinking. My performative exploration of these interests was emboldened by the aptness of the rose-motif to an endless recurrence of the same lyric with difference. Roses bloom and die quickly – so carpe diem, gather the rose! – and yet, they recur. A rosebush on the eastern wall of Hildesheim Cathedral in Germany is said to be 700 years old. Which rose, on which day, in which year, do I gather? And who am I?

Through the gap I saw a flash of Rose

getting ready in her greens

a hint of

a gorgeous slice of girl.

Wait. When did she change into

that pink and low-cut dress?

There was space for me in green,

its partial aspect, delectable hue.

But now I bounce ridiculously off

her self-drawn beauty spot. Aghast.

My sugar, the world’s sweet in,

trifles with me.

So passes passing glimpse to full view,

oblique to frontal, and it’s in that

passing that I lose the object.

Green I could show up against,

in pink I am forgot.

Sometimes change is death,

and sometimes it is not.

In preparation for the MacLean panel, I translated Tasso’s song of the rose, and then I translated my own translations nine or ten times successively. These intervening poems are translations getting ever more unmoored from their source, but they are also my attempt to creep up on Spenser’s ‘some one’ from behind.[27]

Vérde, the colour called greene, or vert in armorie. Also new, yong, fresh, youthfull, in prime. Also the greene grasse. Also a greene, or greene plot of ground. Petrarke hath used the word Vérde for a finall end, when he saith, giónto al vérde, alluding to a Candle, which they were wont to colour greene with the juice of hearbs at the big end, and to this day use it in Ireland, as we would say in English, burning in the socket, decaying, drawing to an end, almost consumed, or beginning to faint.

In the text you are reading now, I have interspersed four of my translation poems between Tasso and Spenser’s lyrics, in the order in which they were written (although they were not written consecutively; there are a number of ghost-poems lurking in-between them).

A certain blazing star

– the sun, let’s say –

wrapped in fog

for a coy reveal,

is something to be seized upon:

a red-hot maid

to torture men with.

The problem for carpe diem is green.

Its absolute resistance to the passing

of time. Rot is green

and so are youthful herbs

almost consumed. Green:

the flash of sunset

turning over in the bed of dawn.

A bright new green uncurling

into a dark green forever.

Backwards of a glimpse is

the whole vision.

All that we know

in prime or in conclusion

is the feeling of

burning green at the big end of love

in a blazing uncertainty.

Although my translations of Tasso are intentionally wayward, I did use a dictionary: John Florio’s 1611 edition of Queen Anna’s World of Words. This is the source of the definitions included throughout this text.

Vérgine, a virgin, a maid, an undefiled damzell. Also one of the twelve signes in the Zodiacke. Also a kind of tormenting iron to torture men with.

Vergitatióne, often bending.

Vergógna, Shame, reproach, infamie, dishonor.

I began consulting Florio’s dictionary regularly while writing a dissertation chapter about Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata. I soon realised that I had never yet looked up a word from Tasso’s epic that I hadn’t found in Florio’s dictionary, often in the exact form in which it appeared in the poem. That is how it dawned on me that Florio was using Tasso’s epic as a source of words to translate (I’m glad I did not check the list of sources in the front of Florio’s dictionary, which would have told me this before I could discover it myself, for the magic was in the discovery). Just when I thought I was the one reading Florio, I discovered Florio reading Tasso over my shoulder. I wanted to attempt writing from this position, putting Florio’s definitions to work in successive translations of Tasso’s song, translations that would be increasingly shaped by my own interference as they worked their way towards Spenser’s song.

Uncertain and unsure for whose sake

shame has me, as so often, bending my neck,

(the crime in here becoming the crime out there

causing the crime in here)

I claim my infamies for myself or I am nothing at all,

for these same monsters are not these indeed.

My attempt to dwell between Tasso and Spenser’s carpe diem lyrics also took me to a physical place: the rose garden in Woodvale extra-mural cemetery in Brighton, where every single rose bush is dedicated to the memory of a lost loved one. This is where I filmed the footage that I played alongside my reading of the poems, and from which I have taken the images interspersed here. It was the second day of May, the rose buds were just beginning to appear, and some mourners, impatient in their love, had bought cut roses in full bloom, burying them in the ground amongst the immature bushes.

The whiles some one did chaunt this lovely lay;

Ah, see, who so fayre thing doest faine to see,

In springing flower the image of thy day;

Ah see the Virgin Rose, how sweetly shee

Doth first peepe foorth with bashfull modestee,

That fairer seemes, the lesse ye see her may;

Lo see soone after, how more bold and free

Her bared bosome she doth broad display;

Lo see soone after, how she fades, and falls away.

So passeth, in the passing of a day,

Of mortall life the leafe, the bud, the flowre,

Ne more doth florish after first decay,

That earst was sought to deck both bed and bowre,

Of many a Lady’, and many a Paramowre:

Gather therefore the Rose, whilest yet is prime,

For soone comes age, that will her pride deflower:

Gather the rose of love, whilest yet is time,

Whilst loving thou mayst loved be with equall crime.

(Spenser, The Faerie Queene, II.xii.74-75)

I am very grateful to Will West, Joe Moshenska and the International Spenser Society for giving me the opportunity to experiment in this way, and I would love to hear more from other ‘some ones’ about their translational journeys towards or away from Spenser.

[1] Accounts on this performance by Jane Grogan, Tiffany Jo Werth, Linda Gregerson, Stephanie Elsky, Patricia Palmer, Deanna Rankin, Nathan Szymanski, Sarah Van der Laan, and William N. West were published as ‘Reflections on “Spenser, Poetry, and Performance’ at Shakespeare’s Globe, 12-13 June, 2017’, in The Spenser Review 49.1.2 https://www.english.cam.ac.uk/spenseronline/review/item/48.1.2/

[2] See, for instance, Mary Thomas Crane, ‘What Was Performance?’, Criticism 43 (2001): 169-187.

[3] Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann, ‘Deformance and Interpretation’, New Literary History 30, (1999): 25-56.

[4] Robyn Schiff, ‘Information Desk’, The Yale Review 107 (2019); https://yalereview.org/article/information-desk. See also Schiff’s reflection on form and information in this poem, ‘A New Direction in American Poetry’, The Yale Review 107.4 (2019): 148, 117.

[5] E.K. on l. 19 of “Aprill”, The Shepherd’s Calendar.

[6] Adam Smyth, Material Texts in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), chapter one.

[7] John White, Briefe and easie almanack for this yeare (1650), title-page.

[8] Folger V.a. 395.

[9] My thanks to Dennis Duncan for advice on searching full-text databases.

[10] Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann, ‘Deformance and Interpretation’, in New Literary History 30.1 (Winter 1999), 25-56. For an enactment of the potentials of this kind of criticism, see Randall McLeod, ‘Tranceformations in the Text of Orlando Furioso,’ in Library Chronicle of the University of Texas at Austin, (1990), 61-85.

[11] All quotations from the Amoretti, in Edmund Spenser: The Shorter Poems, ed. Richard A. McCabe (London: Penguin, 1999).

[12] Louis Martz, ‘The Amoretti: “Most Goodly Temperature”’, in Form and Convention in the Poetry of Edmund Spenser ed William Nelson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), p. 162.

[13] Elizabeth Biemann, ‘“Sometimes I … mask in myrth lyke to a Comedy”: Spenser’s Amoretti,’ Spenser Studies, Vol.4, (1983), 131-141 (p. 132).

[14] Thomas Roche Jr, ‘Astrophil and Stella: A Radical Re-Reading’ in Sir Philip Sidney: An Anthology of Modern Criticism ed. Dennis Kay, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987: pp.186-187.

[15] Martz, (1961): 157.

[16] James Fleming, ‘A View from the Bridge: Ireland and Violence in Spenser’s Amoretti’, Spenser Studies Vol. 15, No. 1, (2001): pp.135-164: 156.

[17] Walter Ong, Ramus, Method, and the Decay of Dialogue: From the Art of Discourse to the Art of Reason (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 151.

[18] Petrus Ramus, Professio Regia (Basel 1576)

[19] Johannes Andreae, Super Arboribus Consanguinitatis Affinitatis et Cognationis Spiritualis et Legalis (1478)

[20] Peter Apian, Cosmographia (1539)

[21] Andrea Palladio, I quattro libri dell’architettura (1570)

[22] Athanasius Kircher, Mundus Subterraneus (1669)

[23] Charles Joseph Minard, Carte figurative des pertes successives en hommes de l’Armée Francais dans la campagne de Russe 1812-1813 (1869).

[24] Peter Galison, Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 19-31. See also James Elkins, The Domain of Images (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1999), Chapter 13: “Schemata,” 213-35.

[25] John Florio, Queen Anna’s New World of Words, or Dictionary of the Italian and English Tongues (London: printed by Melch. Bradwood and William Stansby, for Edw. Blount and William Barret, 1611), s.v. “rósa.” Proquest.

[26] Patricia Parker, Literary Fat Ladies: Rhetoric, Gender, Property (New York: Routledge, 1987, repr, 2017), 54-66.

[27] I was inspired in this attempt – in an admittedly oblique way – by Harry Berger’s account of “textual critique” in “Wring Out the Old: Squeezing the Text, 1951-2001,” in David Lee Miller and Harry Berger, Resisting Allegory: Interpretative Delirium in Spenser’s Faerie Queene (Fordham University Press, 2020) 143-69. Berger’s analysis of “specular tautology” also informs my poetic translations, particularly the last one.

52.3.5

Comments

To perform, especially in the English of the sixteenth century, suggests carrying a process through to an endpoint, not just playing back something already fixed, but reaching it, or reaching toward it, across time.

Link / ReplyThe first thing that occurred to us was again to solicit passages of Spenser, now to be read by the volunteers who chose them instead of passed to actors to play them.

Link / ReplyThese examples should make it obvious that participants agreed a variety of topics, including rhetoric, sound, affect, and geography, may all be diagrammed, in addition to the type of diagram used.

Link / ReplyMost obviously, none of the participants in 2022 were actors, even if as teachers we are also performers.

Link / ReplyThis is where I recorded the video that I played as I read the poems and from which I took the pictures that are scattered throughout.

Link / ReplyTo perform, especially in the English of the sixteenth century, suggests carrying a process through to an endpoint, not just playing back something already fixed, but reaching it, or reaching toward it, across time.

Link / ReplyThe fun began at a little after noon with a spin on the wheel of fortune à la Spenser@Random.

Link / ReplyMost obviously, none of the participants in 2022 were actors, even if as teachers we are also performers

Link / ReplyIt was the second day of May, the rose buds were just beginning to appear, and some mourners, impatient in their love, had bought cut roses in full bloom, burying them in the ground amongst the immature bushes

Link / ReplySo cool. I find this so informative. Keep us updated!

Link / ReplyThese intervening poems are translations getting ever more unmoored from their source, but they are also my attempt to creep up on Spenser’s ‘some one’ from behind.

Link / ReplyThe first thing that occurred to us was again to solicit passages of Spenser, now to be read by the volunteers who chose them instead of passed to actors to play them.

Link / ReplyWhat other forms of performance might be imagined for Spenser’s writing?

Link / ReplyWhat a nice post. I enjoy reading this one!

Link / ReplyIt is an example as well as a representation of poetry acting.

Link / ReplyThank you for keeping us here posted with great content.

Link / ReplyIt's worth the long read. Great work!

Link / ReplyGlad to check this informative site. Thanks for the share.

Link / ReplySuch an awesome post. Thanks for sharing this one!

Link / ReplyThanks for the content you shared!

Link / ReplyThis is a great post. Thanks for taking the time in sharing this here.

Link / ReplySpenser and Performance, Encore: the MacLean Lecture" offers a captivating exploration of Edmund Spenser's work through the lens of performance. By examining how Spenser's poetry interacts with the performative aspects of language, this lecture promises to shed new light on the dynamics between text and enactment in Renaissance literature. With its innovative approach, it invites audiences to reimagine Spenser's works as vibrant, living pieces that transcend the confines of the written page.

Link / ReplyHow then, though, to perform Spenser thus?

Link / ReplyI enjoy reading your post. Thanks for sharing!

Link / ReplyYou must log in to comment.