Memory Club aims to bring together scholars from diverse disciplines to reflect on themes related to vivid remembering. The first meeting took place at the University of Cambridge on 27 February 2025, with a discussion focused on ways of understanding and portraying vividness.

?

Photograph © Anna Spencer.

Kicking off proceedings was art historian Christina Faraday, who gave a presentation on liveliness in Tudor art based on her recent book. Christina introduced the ancient rhetorical concept of enargeia, or vividness. The Roman rhetorician Quintilian (c. 35–c. 100 AD) highlighted three crucial components of vivid speech or writing: detail, multisensory appeal and dynamic narration (that is, events unfolding in real time for the listener). Tudor artworks similarly endeavoured to draw viewers in by telling rich stories.

However, it’s hard to come up with a model of vividness that accounts for variations in how listeners might perceive or process things. For example, some people might find hyper-realistic images or highly detailed accounts especially vivid. Others might be more engaged by accounts that leave blanks they can fill in imaginatively. One of the primary challenges for the ‘When Memories Come Alive’ project will be to develop a model of vividness that is relevant across disciplines, and reflects individual cognitive differences.

?

National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Memorial portrait of Sir Henry Unton, painted c. 1596. The portrait seeks to tell the story of Unton’s life.

The next talk was by Will Duckett, a PhD student in Psychology. His research offers insight into the visual qualities of memories. Humans imagine and remember in different ways. Some people can easily conjure up images in their mind’s eye. But something in the region of 2-6% of people seem to be aphantasic, meaning that they cannot formulate mental imagery. (To find out where you lie on this spectrum, try the Vividness in Visual Imagery Questionnaire.)

?

Bafuncius, mental phantasia representation, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

A simple aphantasia test. If you try to visualise a red triangle, what do you see?

People who can visualise imagery vividly tend to think they have good memories; people with lower vividness scores are more likely to assess their memories negatively. Interestingly, though, they’re not necessarily right. There is no correlation between higher vividness scores and better performance on memory tests. We need more academic exploration of the role of the senses in remembering, again with attention to individual difference.

The rest of the Memory Club session focused on how memories are portrayed in video games. Key to understanding memory is appreciating that it is reconstructive, not reproductive. That is, our memories do not function like video reels our brains can play back on demand. Instead we actively recreate memories every time we revisit them. Video games often give a misleading perspective here, presenting memories as views of the past that always replay accurately and identically regardless of what’s going on in the present.

Project member Charles Fernyhough has worked with the team behind the game Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice. Charles offered guidance on strategies for portraying subjective experience, particularly with reference to voice hearing. The game was widely praised for its sensitive and immersive journey into the mind of a young woman with psychosis. The teams behind Hellblade and its sequel, Senua’s Saga: Hellblade II, are also interested in exploring fresh ways of portraying memory within games.

?

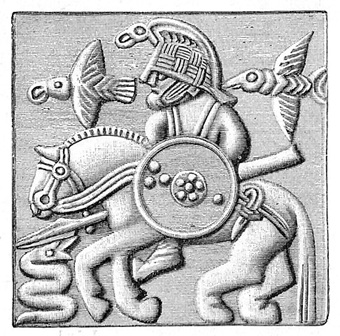

Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

A plate from a Vendel era helmet thought to show the Norse god Odin, flanked by his ravens Huginn and Muninn. Huginn is an externalisation of Odin’s thoughts, and Muninn of his memory and will.

Elizabeth Ashman Rowe, who works on Scandinavian studies and was also an advisor for Hellblade, highlighted how the games explore different cultural understandings of memory. In Norse society, memories could be externally maintained. Communal memories might be perpetuated through oral tradition, engraved on landscapes or encased within the rigid structures of skaldic poetry. This was represented in the first Hellblade game by lorestones, objects scattered throughout the game that told fragments of stories remembered by the protagonist. The second game substituted Lorestangir, totems featuring scraps of skaldic verse.

Within Norse culture, then, vivid memories might be those that were especially well-rehearsed or prominently displayed within communities. This raises further questions: to what extent are memories the product of individual brains, and to what extent are they collective cultural constructs? Does this vary significantly over time and between societies?

Next we heard from another Hellblade advisor, the psychiatrist and neuroscientist Paul Fletcher. Paul highlighted the importance of understanding the brain as a dynamic system seeking to regulate another dynamic system – the world around it. Memory is an adaptive, fluid and constantly updating process geared towards optimising interactions in the present. A realistic portrayal of memory in games should give a sense of past and present colliding, with memories bleeding into perceptions and constructions of the world in the present.

In closing comments, Hellblade II writer Lara Derham similarly considered the value of moving away from the idea that memory is fixed and plays out in cutscenes, towards a model where past memories are alterable (even if the past itself is not). Reflecting on the reconstructive nature of memory will be important as the project team works to refine the concept of ‘vividness’. Perhaps more vivid memories have more obvious threads between past and present, or perhaps vividness depends in part on state of mind in the present.

In between the presentations there was time for discussion within groups, and many more questions arose, including about appropriate methodologies for running experiments on memory and the links between memory and imagination. There is significant variation both in the questions that different disciplines ask about memory, and in how they go about formulating answers. We are grateful to all of the Memory Club participants for helping us to navigate this terrain. We will be relying on their expertise and insights as the project unfolds, and look forward to sharing more of our findings in return.