The second Memory Club meeting took place on Thursday 3 April 2025. It explored memories of dreams, and popular myths about memory.

?

Photograph © Anna Spencer.

In the first half of the session, project team members Raphael Lyne and Charles Fernyhough discussed reality monitoring and literary representations of vivid memories. Reality monitoring refers to the cognitive processes the brain employs to distinguish between things that happen in the external world, and things that are internally generated, like thoughts or fantasies.

Raphael talked about dreams in Shakespeare. Continuing an established literary tradition, Shakespeare vested dreams with meaning and narrative coherence. Through characters’ accounts of dreams or dreamlike experiences, he explored how we reconstruct and make sense of strange mental impressions, and form judgements about what is and isn’t real.

?

Father Ted, season 1, episode 1. Courtesy of Channel 4.

In Richard III, the Duke of Clarence is imprisoned in the Tower of London and passes a ‘miserable night’ dreaming about drowning and going to Hell. He recounts his dream the next morning to a jailer (tower lieutenant Robert Brackenbury, or an unnamed keeper, depending on the version). The jailer interjects twice. First he questions Clarence’s elaborate descriptions of the wrecks and skulls he saw while drowning: ‘Had you such leisure in the time of death / To gaze upon the secrets of the deep?’ He then wonders how Clarence managed to stay asleep after dying: ‘Awaked you not with this sore agony?’ Stage and film versions often omit these interjections, letting the audience get swept up Clarence’s morbid reverie. Shakespeare’s original version prods and pokes at the dream, confronting the literary tradition of contrived dream narratives with the messy realities of perception and cognition.

?

Richard III (1995), dir. Richard Loncraine.

Clarence’s dream performed by Nigel Hawthorne. A heavily abridged version that omits the jailer’s interjections, but captures Clarence’s sense of foreboding.

Charles spoke about psychological research on dreams and reality monitoring. In a 1984 study, researchers asked participants to report on their own dreams, dreams they had read about, and dreams they had experienced. When they later tested how well participants recalled these reports, they found that people more quickly remembered dreams they had read or made up than dreams they had actually experienced.

The study suggested that memory traces of cognitive operations (in this case, the mental work of reading or imagining) help us to identify when something was internally generated. The cognitive work of dreaming is unconscious, making it harder to distinguish dreams from things we perceive in the external world. Clarence’s jailer was offering a kind of reality monitoring, pointing Clarence back towards the cognitive processes underpinning his dreaming. Clarence, however, remained burdened by the sense that his dream was more than a mere mental fabrication. It did, in the end, prove prophetic: Clarence died by drowning, albeit in a barrel of wine rather than the glittering ocean depths.

?

British Library, MS Cotton Nero A X/2, f. 42r. Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

Miniature from the Pearl Manuscript (c. 1400), illustrating a dream vision.

A more recent paper stresses how dreams mix fragments from multiple memories. The dreaming brain is hyperassociative – that is, it links together weakly related memory elements. But memory functions in fundamentally similar ways whether we are awake or asleep: the brain constructs narratives out of particular episodes from our lives.

Some cultures draw stark divisions between dreams and memories of waking experiences. Medieval thinkers conjectured that dreams were divinely inspired, or caused by the soul wandering free of the body at night. Poets, monks, theologians and mystics recorded didactic dreams about journeys to the afterlife, ascribing spiritual profundity to the dreaming brain’s otherworldly narratives. But memories are divorced from reality in similar ways to dreams. Perhaps if we stopped expecting them to look like logical, orderly and accurate representations of real experience, the subjective experience of remembering would begin to more closely resemble that of dreaming.

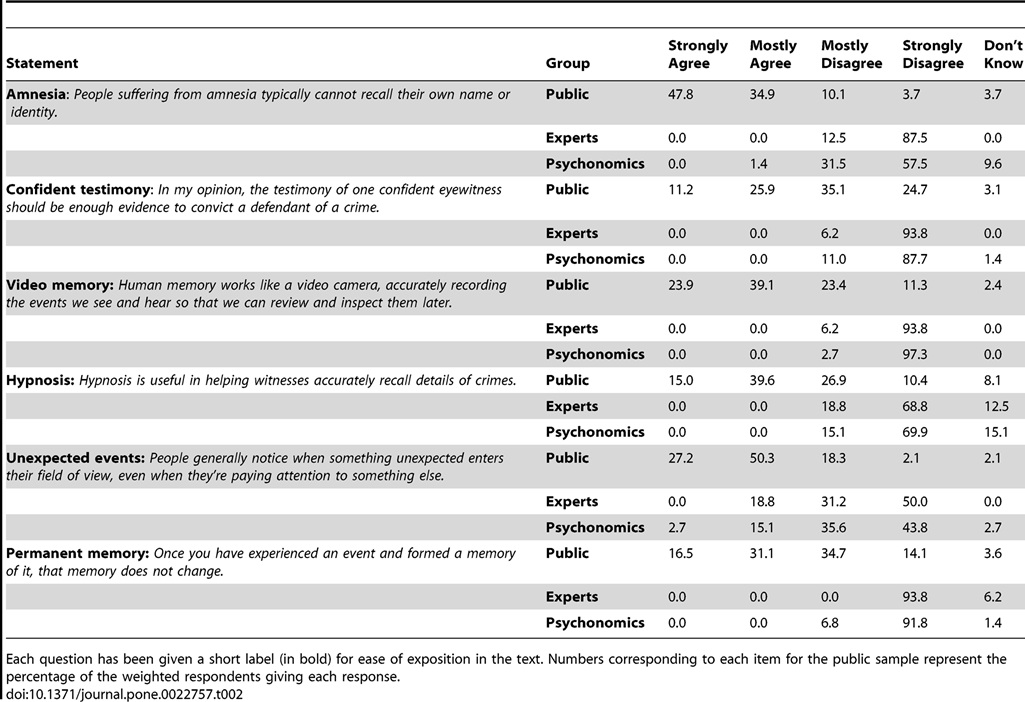

The second half of the session considered Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris’ 2011 survey about memory myths. Simons and Chabris questioned 1500 people on their beliefs about memory, and found that popular ideas of memories differed sharply from expert understandings. John Sutton, director of Stirling’s Centre for the Sciences of Place and Memory, and project team member Martha McGill reflected on the survey from a historical perspective, with a particular focus on early modern Britain.

?

Daniel J. Simons and Christopher F. Chabris, ‘What People Believe about How Memory Works: A Representative Survey of the U.S. Population’, PLoS One 6(8) (2011), e22757, Table 2. Creative Commons.

The questions posed by Simons and Chabris, and answers from members of the public, memory experts and members of the Psychonomic Society.

John emphasised the diversity of early modern understandings of memory. ‘Experts’ might span poets, judges, philosophers, physicians, theologians and philosophers of mind, all of whom had differing perspectives. The ‘public’ was no more unified a category. Even single individuals might hold seemingly contradictory notions of memory.

Consider the statement in the Simons and Chabris survey that ‘human memory works like a video camera, accurately recording the events we see and hear so that we can review and inspect them later’. Early modern culture had various parallels to the video camera analogy: memories were metaphorically encased in libraries, gardens, cabinets or aviaries. But it does not follow that early modern culture had a simplistic notion of memories as passively stored, exhaustive and necessarily accurate. Early modern people theorised that memories could be impacted by evil spirits, bodily disorders, or mere inattention.

Surveys can be a problematic tool for getting at people’s understandings of memory, because there is often a distinction between what people say and what they do. Early modern culture had rich practices of memorialisation. Research on cognitive ecologies has shown how place memory could be deeply social and dynamic. To find memories coming alive in the early modern period, it might be necessary to look beyond writing about memory and explore other contexts in which people remembered in multisensory, affective, embodied, perspectival and permeable ways.

?

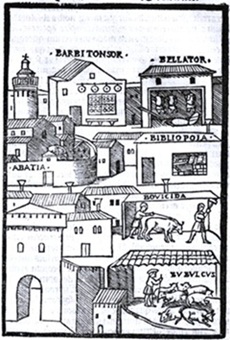

Johannes Romberch, Congestorium artificiose memorie (Venice, 1520), bk. 2, ch. 8. Google Books, Public Domain.

The technique of memory mapping advocated mentally arranging memories in structures like palaces. This illustration is from a book on memory by the German monk Johannes Romberch, who recommended organising memories in an imagined city.

Finally, Martha offered some examples from research on Protestant life-writing. Memory was a crucial tool for godly writers: it was by remembering their past sins and God’s goodness to them that Christians advanced in faith. The London-born diarist Sarah Cowper explained in 1703 that ‘it is memory alone that enriches the mind which doth supply the soul with those Divine Excellencies whereby it is prepared for a glorious im[m]ortality’.

Spiritual writers typically trusted that God would ensure the accuracy of their memories, at least when it came to matters of importance. Jane Turner published her memoirs in 1653. She explained that she was nervous she would forget or misrepresent circumstances, but got assurance from the Lord that he would ‘bring things to [her] remembrance’. But without God’s guidance, memories were subject to all kinds of deficiencies, reflecting the frailty and corruption of postlapsarian humankind. Remembering and forgetting was imbued with emotional resonances and described in languages that would be unfamiliar to most people today.

The diversity of ideas about memory that Simons and Chabris highlighted could be framed more broadly: not only are modern-day experts at odds with the public, but humans across time have understood memory in very variable ways. Does this reflect fundamental differences in the subjective experience of remembering, or only in the conceptual frameworks used to explain memory’s operations? This question will guide our future research.