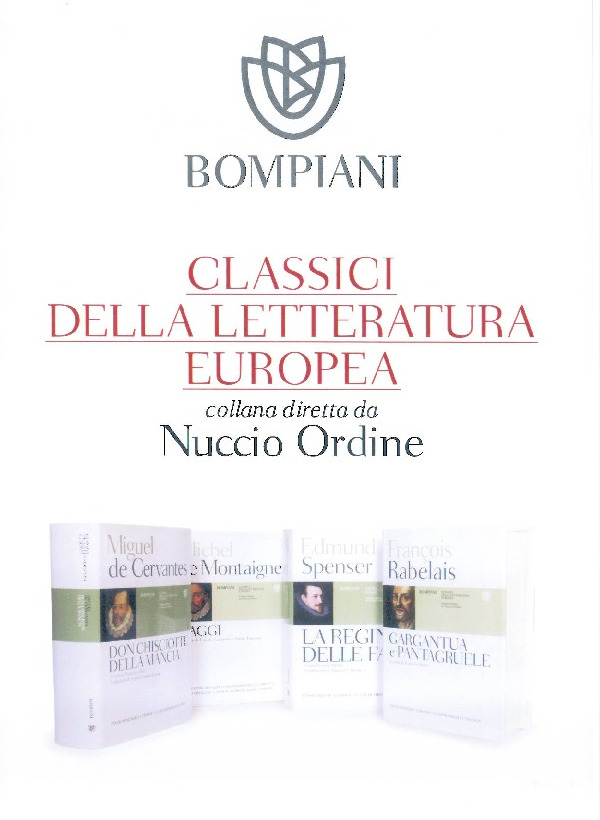

When I was asked by Nuccio Ordine for a contribution to “Classici della letteratura europea,” a new collection devised by himself, it seemed to us both that the poem by Edmund Spenser, which had never been completely translated into Italian, would, considering the very strong bond between Spenser and our country and literature, fill a gap in Italian culture.

With his Faerie Queene, Spenser meant to give England the epic (or heroic) poem that it still lacked. His aim was the celebration of the Tudor dynasty, in particular of Elizabeth I, idealized and glorified through the figures of Gloriana (the Fairy Queen, indeed), powerful and righteous, and Belphoebe, the wonderful and virtuous maiden; the celebration of English nationalism, which had been growing increasingly stronger since the Hundred Years’ War, as Shakespeare reminds us in his Henry V; and the celebration, as well, of the Church of England, which was one of the main expressions of this new sense of nation. Let us not forget, though, that this celebrational purpose is combined with a supreme poetic and mythopoeic sense that goes beyond mere courtly homage.

In composing his poem, Spenser was certainly inspired by the models of Homer and Virgil; but in England, by the sixteenth century, coeval Italian writers—Ariosto and Tasso above all—were also included in the concept of “classic.” Just think of these dates: in 1580/1581 Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata was published; the first three books of the Faerie Queene were published in 1590. Only ten years between the two poems, with Spenser already able to adjust his own garden of Acrasia to Tasso’s garden of the sorceress Armida; while the song heard by Sir Guyon and the Palmer is a rendering of the song of the parrot heard by Carlo and Ubaldo.

Moreover, Spenser named his sorceress Acrasia, while Gian Giorgio Trissino put a sorceress named Acratia in his poem L’Italia liberata da’ Goti (which unfortunately people here in Italy no longer read much). Beside Orestes and Pylades, Spenser included in a list of famous pairs of friends Titus and Gisippus, a pair celebrated by Boccaccio in his Decameron; and he gave readers of that time not a word of explanation, relying on their ability to place Titus and Gisippus in their natural context. Many lyrical inserts in the poem are also patterned after Petrarch’s Canzoniere. The sixth book of The Faerie Queene, devoted to courtesy, starts by mentioning the “civill conversation,” which is La civil conversazione by Stefano Guazzo, one of the three major codifiers of behavior, together with Baldassarre Castiglione and Giovanni Della Casa. As regards mythology. Spenser drew heavily not only on classical sources such as Ovid’s Metamorphoses but also on Boccaccio’s Genealogie Deorum Gentilium.

Poetic form was influenced by Italian style, too. Starting from Italian ottava rima, Spenser, led by emulation and defiance, deliberately added a ninth line, inventing this way a verse form that would go down in history as the Spenserian stanza. It is worth saying, now, something about the translation into prose that Italian readers can now enjoy. At the beginning, a rendering in poetry was a tempting choice, and the first attempts were in fact made in that vein. One of the main difficulties consists in the frequent recurrence of monosyllables and disyllables in the English language, which lets an English poet make use of up to ten words for an iambic pentameter—something impossible for an Italian hendecasyllable. Translating the one into the other would involve the loss of at least a third of the text, which I do not consider an acceptable solution for a dense poem such as Spenser’s, where every word has its own value that treasures up and reverberates on the rest of the text. So I picked prose as my choice, and I tried to make it as fluid as possible by giving it a poetic tendency consistent with the morphosyntactic complexity of Spenser’s style; and I gave the Italian text what I like to call a “hint of antiquity,” all the more so because Spenser’s language was perceived as archaic even by his contemporaries.

In conclusion, let me recall a word that I particularly loved, which has accompanied me throughout this whole long effort: I want to isolate it from the flood of words comprising the poem: it’s chevisaunce, which means “chivalry,” but also the whole ensemble of chivalric acts and virtues; Spenser made it rhyme with chauce, a variation of “chance,” fortune; this rhyme connects the two words and subordinates the strict chivalric code to chance, so that the term chevisaunce is both deprived and enriched at the same time.

In 2005 I presented Spenser’s Petrarchan sonnet sequence, Amoretti, to Italian readers: but nobody noticed. I hope that this translation of his poem will help give Spenser the place that he deserves in Italian culture.

Luca Manini

Note sulla traduzione italiana della Faerie Queene di Spenser

Quando Nuccio Ordine mi contattò per offrirmi di collaborare alla nuova collana da lui ideata dei “Classici della letteratura europea”, a entrambi parve che la proposta del poema di Edmund Spenser, mai tradotto integralmente in italiano, venisse a colmare un vuoto nella cultura dell’Italia, in considerazione degli strettissimi legami che legano Spenser al nostro paese e alla sua letteratura.

Con la Faerie Queene Spenser intese dare all’Inghilterra il poema epico (o eroico) che ancora le mancava. Suo scopo era quello di celebrare la dinastia Tudor, in particolare Elisabetta I, idealizzata e glorificata nelle figure di Gloriana (la Regina delle Fate, appunto), potente e giusta, e di Belfebe, fanciulla bellissima e virtuosissima; di celebrare il nazionalismo inglese, che si era andato rafforzando nel corso della guerra dei cent’anni, come Shakespeare ben ci ricorda nell’Enrico V; e celebrare, infine, la chiesa anglicana, che di questo nuovo senso di nazione era una delle principali espressioni. Occorre però ricordare che lo scopo celebrativo s’accompagna a un altissimo senso poetico e mitopoietico che supera il semplice omaggio cortigiano.

I modelli che Spenser aveva presenti nel comporre un poema erano, ovviamente, Omero e Virgilio; ma nel Cinquecento inglese il concetto di ‘classico’ s’ampliava ad accogliere anche i coevi autori italiani, Ariosto e Tasso in primis. Basti pensare a queste date: nel 1580/1581 esce la Gerusalemme liberata di Tasso; i primi tre libri della Faerie Queene escono nel 1590; dieci anni soltanto separano i due poemi, e già Spenser poté modulare il proprio giardino di Acrasia sul giardino della maga Armida di Tasso; e il canto che Sir Guyon e il Palmiere odono è una resa del canto del pappagallo udito da Carlo e Ubaldo.

Ancora, la maga di Spenser si chiama Acrasia, e Gian Giorgio Trissino, nel poema L’Italia liberata da’ Goti (un poema che purtroppo noi italiano abbiamo perso l’abitudine di leggere) aveva creato una maga dal nome Acratia … In un catalogo di famose coppie di amici, Spenser inserisce, accanto a Oreste e Pilade, Tito e Gisippo, ossia una coppia d’amici celebrata da Boccaccio nel Decameron; e lo fa senza dare spiegazione alcuna, fidando che i lettori del tempo sarebbero stato in gradi di collocare Tito e Gisippo nel loro contesto naturale. Molti inserti lirici del poema sono poi modellati su versi del Canzoniere di Petrarca. Il sesto libro della FQ, dedicato alla cortesia, si apre nominando la ‘civill conversatio’, ovvero La civil conversazione del nostro Stefano Guazzo, uno dei tre grandi codificatori del comportamento, assieme a Castiglione e Della Casa. E anche per la mitologia, oltre che a fonti classiche come l’Ovidio delle Metamorfosi, Spenser attinse a piene mani dalla Genealogie Deorum Gentilium di Boccaccio …

Anche la forma poetica è debitrice all’Italia. La base è l’ottava italiana, cui Spenser, per un senso di emulazione e sfida, volle aggiungere un nono verso, creando quella che è passata alla storia come la spenserian stanza. E a questo punto occorre dire qualcosa sulla traduzione in prosa che troverà dinanzi a sé il lettore italiano. Forte è stata, all’inizio, la tentazione di una resa poetica, e le prime prove sono state fatte in questo senso. Una delle maggiori difficoltà è costituita dall’alta frequenza che l’inglese ha di parole mono e bisillabiche, il che permette a un poeta inglese di inserire fino a dieci parole in un pentametro giambico, cosa impossibile per un endecasillabo italiano; il farlo comporta la perdita di almeno un terzo del testo, il che non mi è parsa una soluzione accettabile per un poema denso com’è quello di Spenser, dove ogni parola ha la sua valenza da conservare e da riverberare sul retso del testo. la scelta è così caduta sulla prosa, che ho cercato di rendere il più scorrevole possibile, dandole un andamento poetico che fosse fedele alla complessità morfo-sintattica dello stile di Spenser; e ho dato al testo italiano quella che mi piace chiamare una ‘patina d’antico’, tanto più che il linguaggio spenseriano era sentito come arcaico già dai suoi contemporanei …

Permettete che concluda ricordando una parola che ho particolarmente amato, e che mi ha accompagnato durante tutto questo lungo lavoro, una sola parole che mi piace isolare nel fiume di parole che il poema è: chevisaunce, ossia, cavalleria, ma anche l’insieme delle azioni cavalleresche, dei valori cavallereschi; è una parola che Spenser fa rimare con chauce, variante di ‘chance’, il caso, la fortuna: la rima unisce le due parole e sottomette il rigido codice cavalleresco al caso, nel contempo svuotando e arricchendo il lemma chevisauce …

Nel 2005 presentai al pubblico italiano il canzoniere petrarchesco di Spenser, Amoretti, ma nessuno se ne accorse; spero che questa traduzione del suo poema contribuisca a dare a Spenser il posto che gli spetta nella cultura italiana.

Luca Manini

43.1.2