Poston, Michael, Rebecca Niles, and Eric Johnson, eds. Folger Digital Texts. Folger Shakespeare Library. n.d. <http://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/>.

The tagline of the Folger Digital Texts (FDT)—“Timeless texts, cutting-edge code”—reflects its user-oriented design. Its home page offers those users two options: “Read a Play” or “Download the Code.”

Pursue this binary a bit further, and consider two categories of scholars. The first wants to “Read a Play,” to do and teach close readings of passages in a well-designed and reliable edition. Let’s call him philological-citational: he quotes and analyzes passages from a text that happens to be online. And let’s call the second category digital-holistical: the scholar who wants to “Download the Code,” to extract every speech from all available plays and run them through text-analysis algorithms. She wants statistics on which adjectives Shakespeare uses for gendered nouns (man, woman; knave, wench), to compare them with Dekker’s and Jonson’s.

Yes, it’s a false binary: philologists can be as holistic as any digital humanist, and the algorithmic critic will test her results with close readings of multiple passages. The FDT’s “timeless texts” (edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine) are the outward show of its “cutting-edge code” (encoded by Michael Poston and Rebecca Niles). Outward show and inner worth are intertwined, as every undergraduate knows. The FDT doesn’t quite manifest the relationship between texts and code, but it does an exemplary job of supporting scholars who look first to one or the other.

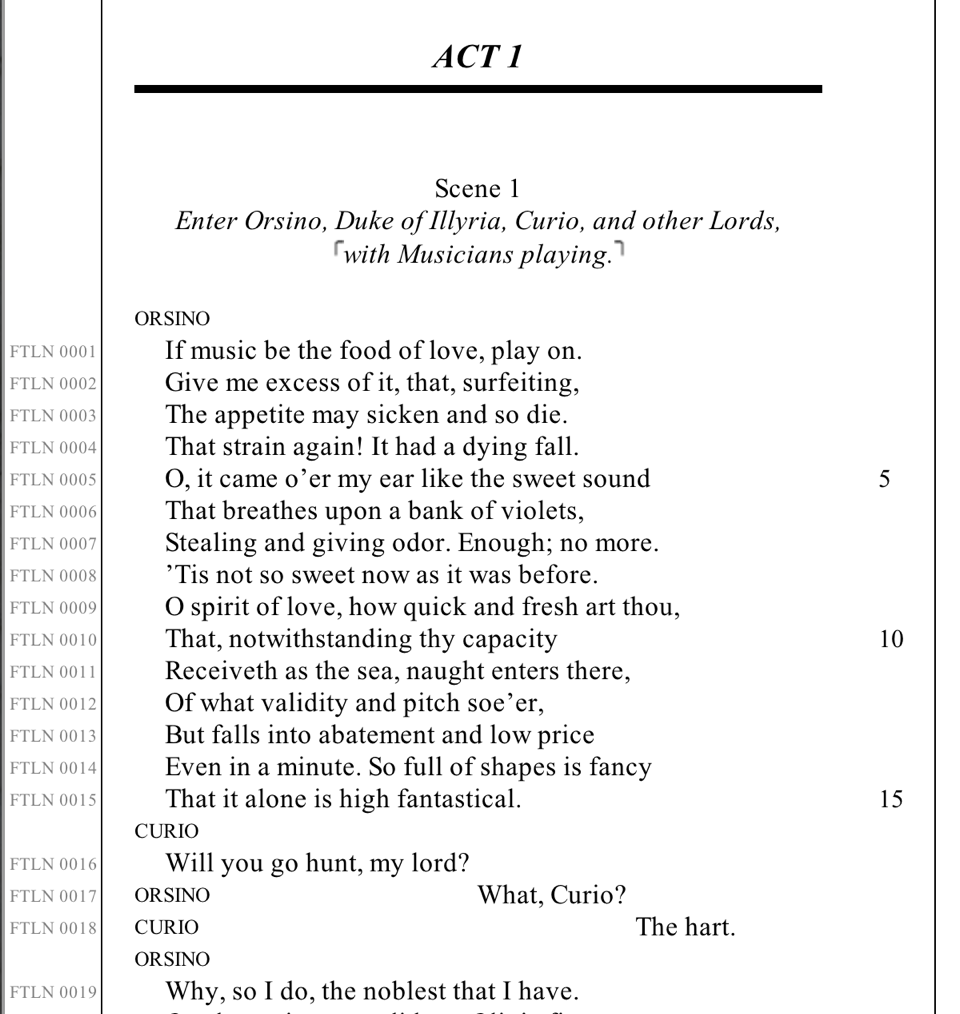

The FDT’s texts themselves are from the Folger Shakespeare Library editions—excluding their illustrations, notes and glosses, and essays. This text is covered by a Creative Commons license for scholarly purposes (specifically, an ”Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License” permitting non-commercial reuse when you cite your source.) Its interface is designed for ease of reading, with texts typeset to mimic their print counterparts. The digital text is divided into pages—or rather, page-length sections—that are paginated to correspond to the pages in the print text. In print, these pages are supplemented by facing-page notes, absent from the FDT. A handy link sends you to an online bookstore to buy your own copy, or to a PDF file of the text alone. I tend to annotate texts in print, so I appreciate these options.

I also appreciate good typesetting and layout, and few online editions are so bookish in their appearance. This is a term of praise, because of its affordances for teaching: it’s easy to imagine projecting the digital edition, searching its contents and navigating through the text of (say) Twelfth Night, while allowing students with the print or digital text to follow along. A “Quick Jump” menu hovers just to the right of the text, allowing readers to move between specific page or line numbers. And every text is prefaced by a linkable table of contents and a synopsis.

The elegant design of the FDT’s interface moves readers between sliding panels, from the home page to the table of contents to the plays. One feature that might break the wall between texts and code would be a “Reveal Code” menu, to pull back the curtain on the text encoding that underlies a digital edition. It might even offer ways for our philologist to work with this code, to extract (say) all of Orsino’s speeches (and his alone), or lists of the stage directions from every comedy, or of all of one play’s speech prefixes divided by scene, or—the mind reels.

Full disclosure: I direct a project to analyze Shakespeare’s rhetorical figures, and have approached the FDT’s developers about how research teams like mine can extract speeches (minus prefixes) from plays, and analyze their clausal syntax. (Knowing that “Featured like him, like him with friends possessed” is two clauses helps identify its anadiplosis.) I understand that the FDT’s editors are working to make this extraction easier, and they know they can’t anticipate every possible extraction and transformation.

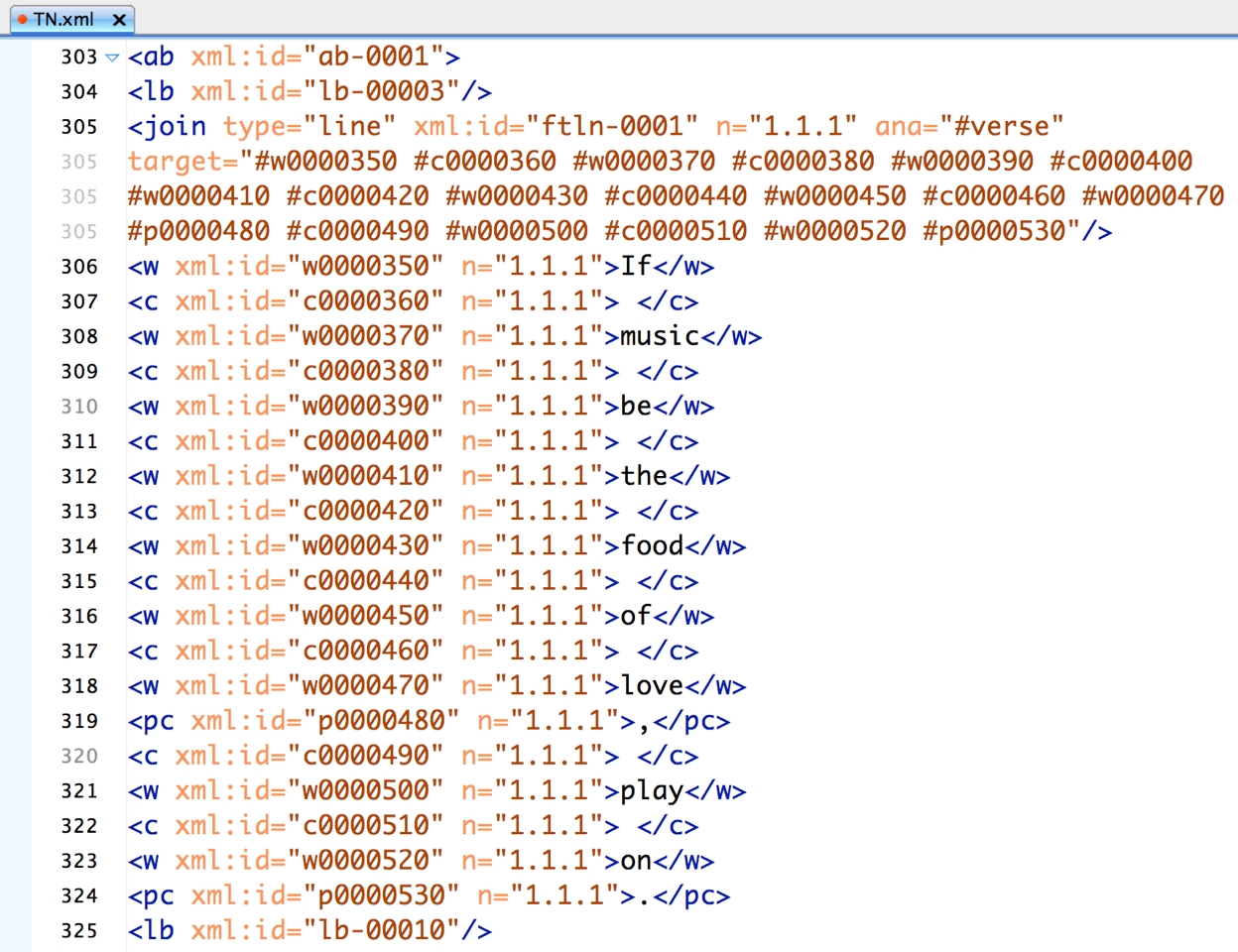

The FDT’s text encoders have made a number of implicit and explicit choices to make this code as open to extraction and transformation as its edited texts are to teaching and reading. For instance, their choice of XML (or eXtensible Markup Language) as their file format leaves the marked-up texts flexible enough to be displayed and manipulated by other programs. In brief, XML is more indifferent to its uses than any other text-encoding file format.

What about the encoding itself? The first principle of text encoding is to do no critical harm—that is, to enable rather than foreclose interpretations. It should be as detailed as necessary but as neutral as possible.

In this respect the FDT’s markup is exemplary. First, a word of explanation. When we say a text is “marked up,” we mean that its features (e.g. words, punctuation) are annotated or encoded with various semantic, descriptive, or other labels. Markup designates the discrete purposes of the words “Act 1,” “Scene 1,” stage directions, and speech prefixes—to say nothing of the words in speeches themselves.

The FDT’s markup applies to matters on which there is little disagreement. Few would argue that Orsino’s opening line is not “If music be the food of love, play on,” but the stage direction “Enter Orsino, Duke of Illyria, Curio, and other Lords.” Everyone agrees, I think, that stage directions are not verbalized. The markup in the FDT’s code divides the text into various segments; for instance, all the stage directions or songs or foreign words are encoded with elements or attributes to make them easily distinguishable. Even within these broad categories, there are further subdivisions: stage directions are split, for instance, between entrances, exits, asides, locations, and other categories.

Markup manifests commonly accepted designations. It can go further, but the FDT’s encoders commendably avoid interpreting the text they are encoding. For example, the encoders decline to lineate the texts, because “Lineation is determined by critical judgments, complicated by accidental features of publication” (TN.xml line 87).[1] Instead, each line is comprised of joined-up words, spaces, and punctuation marks, followed by a line break. The reader sees them as a line, which reflects those critical judgments and accidents—but this display of the encoded line could just as easily ignore the line breaks (turning verse to prose), which would have quite different effects. If a reader wanted to see all the words in red type and the punctuation in contasting green, say, it would be easily done.

So the FDT enables the widest possible range of readings, from humans to machines, close to distant. We and our algorithms can parse neologisms and measure sentence-lengths in one line or in multiple texts, while teaching the next generation of scholars both critical acuity and the computational tools that serve it.

If you’ll permit me one last feature request, it would be the ability to highlight and bookmark snippets of text, and to tag or annotate them. I imagine logging in to the Folger’s site, which is now open to all, to see a virtual bookshelf of the texts I’m teaching in a given course, and granting access to my students—even assigning them the job of assembling their own snippet libraries for a critical essay or class discussion. The students would then learn how to gather, sift, and arrange textual evidence in a critical argument. Yet even with no added features, the FDT is an essential complement to my print editions; its affordances for computational text-analysis are obvious enough, and I will very likely teach one or more of its texts in lieu of print editions.

Michael Ullyot

University of Calgary

[1] Downloadable after registration from http://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/zip/Folger_Digital_Texts_Twelfth_Night.zip.

44.1.7

Comments

Comment deleted 3 years, 1 month ago

Hi. It is very important to hire really qualified specialists to meet all your design needs. From my own experience, I can tell you that they are not easy to find. But I was lucky and found a resource where everyone can <a href="https://limeup.io/blog/ux-design-agency-london/">learn more here</a> about the Top Design Agencies, offering a wide range of choices for business owners.

Link / Reply[url=https://www.english.cam.ac.uk/spenseronline/review/item/44.1.7/#comment-640]learn[/url]

Link / ReplyI have a wealth of experience in the design field, and I'd like to present an interesting proposal. I have a strong inclination for working with vectors, and I believe you might appreciate the use of https://blog.depositphotos.com/summer-photography-ideas.html which can provide a stunning and captivating visual appeal. Many clients have shown a keen liking for this creative approach.

Link / ReplyWith the growth of e-commerce and influencer marketing, affiliate marketing offers significant earning potential. https://instantcasinos.com/

Link / ReplyA handy link sends you to an online bookstore to buy your own copy, or to a PDF file of the text alone. I tend to annotate texts in print, so I appreciate these options.

Link / ReplyYou must log in to comment.