Barr, Helen. Transporting Chaucer. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2014. ix + 276 pp. ISBN: 978-0719001490. $105.00

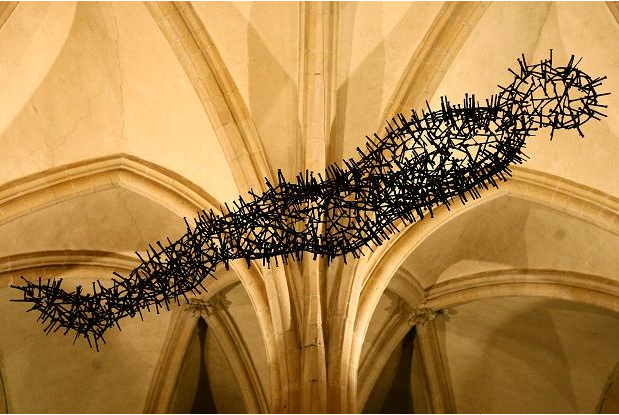

Helen Barr’s new book is about how Chaucer crosses temporal and material boundaries. Spenser does not feature in her account, yet her analysis of the ways that characters, names, and figures move across what we’ve considered to be insuperable literary borders is useful for thinking about The Faerie Queene.[1] Barr takes her project’s galvanizing idea from Transport, Antony Gormley’s 2010 sculpture on display in Canterbury Cathedral when Barr visited:

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/arts/visualarts/article2893672.ece, accessed September 13, 2015

A figure of nails hanging in space, in Barr’s analysis this sculpture conflates bodies—Becket’s and Christ’s—and shows how material, figural, and temporal fixities subside through an unsettling encounter with Chaucerian corpora. For Barr, Chaucer moves through space and time in a way that upends narrative linearity and temporal chronology.

Though she addresses texts from 1340-1700, there is no periodization in Barr’s study because, as she shows, Chaucer’s corpus defies those traditional scholarly partitions. Similarly, Barr is not interested in sorting out an authoritative Chaucerian canon: works that are by Chaucer intermingle with those that are inspired by Chaucer, and those that Chaucer went on to influence. Narrative admixture is abetted by textual commingling: by attending to the manuscript environs of Chaucerian texts, Barr urges a reconsideration of the ways that we understand literary associations. Alison’s role in the Canterbury Tales, for instance, is reshaped by her appearance in the fifteenth-century fragment called The Canterbury Interlude (12-16; 58-60). This story is set in Canterbury despite the fact that it is set in the middle of the manuscript (which means that it occurs halfway through the pilgrimage to Becket’s shrine). As bodies blur, Barr argues, Chaucer becomes a transport for cultural ideas about sanctity, sexuality, and gender. From Lydgate to Shakespeare, and from Davenant to Dryden, Barr unfolds a series of nuanced close readings that show how Chaucer—his persona and his characters—upends authorized versions of literary time and place.

The primary methodology in Transporting Chaucer is close reading. This process is hardly simplistic, since it takes a reader as subtle and determined as Barr to tease out the multiple, tangled, and interspersed connections between Chaucerian bodies. Chapter One is organized by Canterbury Cathedral itself: with analysis of the Canterbury Interlude (also known as the Prologue of the Tale of Beryn), which is set at Thomas Becket’s shrine despite the fact that this addition is positioned halfway through the Canterbury Tales (i.e., before the pilgrims arrive at the Cathedral), Barr reads the narrative’s representations of pilgrim activity through the fragments of Becket’s body. The pilgrims look for healing from Becket’s shrine, but they also show the partial status of the martyr’s sanctity. By focusing on the tale’s pardoner as he resonates with Chaucer’s pilgrim in the Canterbury Tales, and with the pardoners as they are drawn in The House of Fame, Barr uncovers the scandal of bodily continuity that martyr and narrative similarly reveal and evade.

Chapter Two continues its exploration of works by the Beryn-poet, but here Barr analyzes the ways that names lose distinction across Chaucerian corpora. As she suggests, “[T]he characters in the Interlude that share a name with characters in the Canterbury Tales are beside themselves” (57). This contiguity is not just figural, or allusive. She continues, “In MS Northumberland 455 they are beside themselves materially even as the teleology of the Canterbury sequence is upset” (57). Across script and print, no stability can be guaranteed, because these Chaucerian bodies are intermingled by design. The Beryn-poet is a savvy reader of Chaucer, Barr explains, so much so that he borrows the name Gioffrey from the Anglo-Norman romance, Berinus, in a rendering that simultaneously prefigures and remembers Chaucer’s hapless poet-persona.

Literary fragmentation—or the ways that storial bodies and their parts move back and forth across customary boundaries of time and place—is a process that Barr continues to pursue in Chapter Three. In thinking about how hands provide transport in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Barr connects medieval ideas about hands as sources of good, sin, and action. This cultural context leads into her analysis of The Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale and The Summoner’s Tale, both of which show “that the hand is an instrument not of the soul but of transgressive bodies” (94). The hand’s emblematic status in the Middle Ages allows Barr to include manuscript representations of Chaucer’s pilgrims in her considerations. As she notes, there are six pilgrims in the General Prologue whose hands are described, but, when the pilgrims are depicted on horseback in manuscripts, of “all of them display hands that supplement the already discursively wayward hands that are narrated through words” (98). By working through a sample of pilgrims in Ellesmere and Cambridge University Library MS Gg.4.27 (her appendix gives an exhaustive account of hands in illustrated manuscripts), Barr shows how different manuscripts envision pilgrims as wayward bodies.

The most important hand, finally, is Chaucer’s. The final part of the chapter takes up “the discursive unruliness of Chaucer’s ‘own’ hand” (107). Chaucer’s hand points to empty space; it is placed next to the Melibee, even though it is not the first tale he tells. These details lead Barr to the conclusion that Chaucer’s hand is for critics a manicule that seeks to settle the poet’s reputation for serious matter. With a final look at Chaucer’s hands in manuscript copies of Hoccleve’s Regiment of Princes, Barr attends to the ways that these texts seek to establish Chaucer’s posthumous authority.

Chapter Four confronts the tangled temporalities of Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale, Shakespeare’s Two Noble Kinsmen, and Midsummer Night’s Dream. As Barr explains, these texts “are intratemporal; they contain each other’s stories” (142). Principally through an investigation of Emily’s and Arcite’s roles, Barr argues for a “cosynchrous” understanding that erases, elides, or contains desire. Emily, in particular, is a threat to the patriarchal designs of powerful men, namely the Knight and Theseus. Yet despite an attempt to erase her and her chaste will in the marital imperative of Midsummer Knight’s Dream, her Amazonian power “keeps turning up and back” (145). In Two Noble Kinsmen this repression becomes the subject of drama, which means that Emilia’s marital transfer from Arcite to Palamon exposes the violence that subtends patrilineal marriage.

Arcite, too, is a threat to dynastic marriage: “In The Knight’s Tale, and Two Noble Kinsmen, Arcite is the odd lover out—and he dies. Which is why he must be prevented in Dream” (150). Barr argues that Arcite is present in Midsummer, that Theseus’s Master of the Revels—Philostrate—does more than import a name from Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale. This is the identity that Arcite assumes to disguise himself, and, for Barr, that forgotten link is a transport between Chaucerian bodies without respect for linear chronology. As she concludes, “This chapter imagines the parts of Emily and Arcite in A Midsummer Night’s Dream without fixing three texts in the sequence of their historical composition; that is, without setting them in hierarchically bounded time” (156). In concluding her analysis by charting the tangled chronology of these three texts—Two Noble Kinsmen is the “earliest” text for the characters, and the events of The Knight’s Tale happen later than those in either of Shakespeare’s dramas—Barr debunks the idea that traditional source study is a tenable model for thinking through the linkages between well-known literary narratives.

In Chapter Five Barr continues to think about what happens to Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale in later centuries. To consider retellings of this story, however, she suggests that familiarity with the Miller’s challenge to the Knight’s authority is necessary: “[Two Noble Kinsmen] mingles the matter of Thebes and Athens with the licentious holiday world of England” (167). When William Davenant revises Two Noble Kinsmen for the Restoration stage as The Rivals (1664; printed 1668), he imports names from John Lydgate’s fifteenth-century Siege of Thebes. By so doing, Barr suggests, Davenant further erodes the Knight’s authority. To prevent “a restaging of noble annihilation” (168), Davenant alters the ending of The Knight’s Tale; yet, despite its restorative revision, The Rivals remains threatening to noble interests. Lydgate’s narrative is one of fateful destruction, which features unlawful acts of illegitimate offspring. Since Lydgate’s poem was included in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century editions of Chaucer, The Siege of Thebes overtakes The Knight’s Tale, and disrupts the restorative work of The Rivals. With a brief turn to John Dryden, the chapter concludes by emphasizing the “free-for-all that zigzags back and forth in between temporalities, lineages, social rank and generic decorum” (189).

Chapter Six considers Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida alongside Chaucer’s House of Fame to think about sound as a poetic inheritance. Though Barr does not insist that Shakespeare knew Chaucer’s poem, their sonic similarities show the importance of Chaucerian interventions that can no longer be traced. Voices, aurality, and noise: the soundscape of both works “dissolves discrimination between fame and honour, and ignomy and oblivion” (198). Southwark’s noise, which both Chaucer and Shakespeare use to deflate classical Trojan eloquence, becomes the sound of ruin. Vaunting praise sounds like so much street gossip. Voices are not the only mode of shared cacophony: Barr attends to the jarring noise of trumpetry in both texts, noting that Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida contains more trumpet references than any other; these references, she goes on to argue, are associated with the staged futility of reputation. As it is in Chaucer’s House of Fame, glory is a jumble of noise. You can’t hear yourself in these poems, which means that heroic attributes are lost to the whirl of sound that makes up everyday life. The contrasting silences conjured by both Chaucer and Shakespeare “reveal the abysmal oblivion into which the legend of Troy is destined to be evermore spoken” (225).

Though “source study” has long been unfashionable, Barr’s argument calls us to rethink the linear ways in which we seek to connect texts across boundaries of time and place. Chaucer pops up in unexpected literary locales, in unanticipated poetic moments; moreover, his influence is felt in ways that later authors likely never intended. But literary association, Barr demonstrates, does not adhere to the imposed bounds of intentionality. Chaucer’s presence can be constructed by manuscript, or construed by aurality. Chaucer’s corpus is dispersed and regathered by the myriad ways he is engaged and deployed. Barr shows Chaucer’s unusual presence, but that presence, as she concludes in her brief coda, “outface[s] teleology and refuse[s] taxonomy” (246). Chaucer’s embeddedness in later texts is not presented as a feature unique to his literary position, either. Rather, Barr challenges us to see that medieval and early modern texts, especially those that are involved in building a national identity through literature, are enmeshed—materially, temporally, and spatially—in ways that we can acknowledge with a continuous, unclosed process of close reading.

[1] For an apt demonstration of this usefulness, see Dorothy Stephens, “Interpenetration and the Politics of Topology in Spenser and Marvell” in this issue. —Ed.

45.2.36

Comments

This process is hardly simplistic, since it takes a reader as subtle and determined as Barr to tease out the multiple, tangled, and interspersed connections between Chaucerian bodies.

Link / ReplyIf you are tired of low-quality sites for playing online slots in Bangladesh, then I recommend you this site, because on this site you will find a great collection of the best slot machines that you can play freely, because this site is of high quality and has an official licence, which makes it very reliable.

Link / Replygood post here

Link / ReplyThanks so much for such an informative post! In fact, I also love to bet on sports because it really has a positive effect on my mood. Therefore, I would like to recommend using the link to this site https://vasarhely24.com/ where you can definitely find out more information about betting. Just open the link and see how useful it is!

Link / Reply[url=https://kissasian.com.mx/]Kissasian[/url]

Link / ReplyYou must log in to comment.