Six Degrees of Francis Bacon. Christopher Warren, Daniel Shore, and Jessica Otis, Co-Principal Investigators. http://sixdegreesoffrancisbacon.com

Christopher Marlowe, in his Tamburlaine, Part I, alludes in detail to eastern locales and eastern circumstances of his own day, leading Michael Murrin to conclude: “All these details lead to a crucial inference. Marlowe could not have got his information from any persons other than the employees of the Muscovy Company.”[1] Or, in other words, Marlowe drew on his social network for the materials he used in his creative reconstruction of the life of Timur. Six Degrees of Francis Bacon (hereafter SDFB), according to its about page, is “a digital reconstruction of the early modern social network,” but while the goals and the materials of SDFB overlap considerably with traditional forms of literary sleuthing, the procedures involved could hardly be more different.

Murrin’s method may be described as the conversion of narrative into data: wide reading, filtered through the trained intuition of a master practitioner of literary history, leads to an insightful inference of fact. SDFB, on the other hand, starts with data, lots of it, and automatically produces narratives about the social connections recorded in those data. These narratives are neither textual nor sequential—they are called “visualizations”—but each one nevertheless tells a story about a particular set of persons, groups, and the relationships among them. The particular virtue of these visualizations is that a great deal of information can be displayed at once, allowing the user to acquire an intuitive grasp of a set of relationships that would be impossible (or at least quite tedious) when considering only one relationship at a time.

The analysis of social networks has long been familiar to social scientists, and for that matter is hardly new elsewhere. Marketers have always wanted to know whom their customers know in order to market more effectively, and in law enforcement, investigators have always tracked wanted criminals via the criminals’ known associates. What is still relatively new outside the sciences and certain business applications is the creation of large sets of data containing information about social connections, and the intensive application of statistical methods and computer visualization tools to study that information. Now, however, almost anything that can be thought of as a social network is being studied in this fashion, including the fictional networks found in such places as the Star Wars movies or Shakespeare’s tragedies.[2]

SDFB pursues a form of social network analysis very similar to that used by sociologists, which is to say a network of relationships among real human actors, but it starts with a notable handicap: we cannot get the people of early modern England to fill out survey forms, nor can we monitor their social behaviors or electronic interactions. Instead we must infer connections from the surviving written record, and SDFB jump starts this process by drawing its initial data set almost exclusively from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. There are currently just shy of 14,000 people and one hundred groups in the database, connected by some 200,000 relationships.

The benefits of starting from such an established and authoritative source as the ODNB are clear: the multiple years and millions of dollars not spent by starting from scratch. The choice does, however, bring some biases. The SDFB team are well aware of the drawbacks and are working hard to mitigate them, primarily by soliciting community input and providing multiple avenues for users to submit additional data and correct existing data. Perhaps the most glaringly skewed aspect of the network, as Scott Weingart and Jessica Otis eloquently explain in a recent entry on the project blog, arises from the gender bias in the written record, a bias that has been amplified by the gender bias in most periods of historical research, and finally amplified even further by the data mining methods used to identify relationships.[3] The good news is that the formation of a working group to address gender bias in the data set will not only make palpable reductions in this bias, it will also provide an exemplary model for other community efforts to correct, supplement, and curate the data.[4]

One problem may arise as the data grow organically from user submissions: whatever imperfections the ODNB data bring with them, they at least have a degree of consistency, while more subtle and less tractable biases may emerge as different parts of the data grow and are refined by different hands at different times. But this is to say nothing more than that SDFB is likely to be successful enough to create new intellectual challenges for itself, challenges that may be unfamiliar to many humanists but that its multi-disciplinary team—which includes specialists in data curation and mathematics as well as literature and history—appears well-equipped to handle.

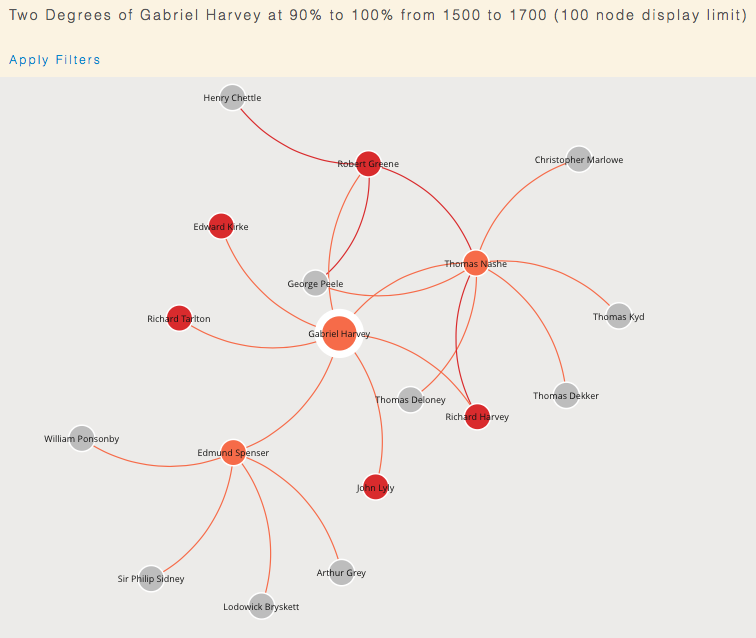

While the data underlying SDFB are a work in progress and expected to remain so indefinitely, the user interface is extremely polished and user friendly despite the prominent claim that the software is still in beta. The balance of rich features and simple presentation is especially well done; each screen or view provides a manageable set of features and options; those features and options not immediately relevant are hidden from view but readily called up via expandable choice bars and a few carefully chosen menu options. The most basic feature is searching for the social connections of a particular individual, and the result of such a search is shown in Figure 1, which displays the first- and second-degree connections of Gabriel Harvey.

Figure 1.

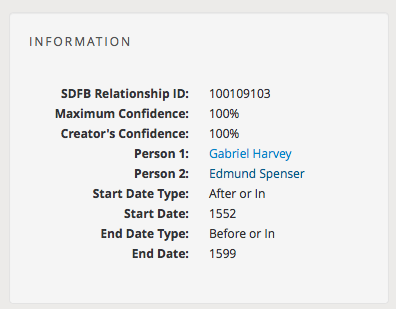

The colored circles in the network graph represent direct connections, and the gray circles represent second-degree connections. Moreover, the graph is interactive: it may be panned and zoomed; hovering over any line causes the names of the persons it connects to appear as a tooltip; and finally, clicking on a line allows us to drill down to more detailed information about the relationship the line represents. For example, if we click on the line joining Gabriel Harvey to Edmund Spenser and then click again on the “More Information” button that then appears in the left bar of the screen, we’ll be shown in textual form the data behind that line in the graph, shown here in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

The confidence level is, according to one of the site’s frequently-asked questions, “the likelihood, based on our statistical models, that a particular relationship existed.”[5] A confidence of 100% seems completely warranted in the case of Gabriel Harvey’s acquaintaince with Edmund Spenser given the well-known surviving records, including published letters, that indicate without a doubt that Spenser and Harvey knew each other. There is little guidance, however, on the meaning of lower confidence rankings other than that a lower number means less confident, and there is insufficient information available to independently reproduce the confidence calculations.

It should also be noted that the confidence level does not apply to the dates of acquaintance, which instead represent—at least in the case of Harvey and Spenser—outer boundaries rather than known years of association. Obviously it is much more likely they became acquainted when Spenser matriculated at Cambridge in 1569 than that they knew each other as infants in 1552, but such specialist knowledge is not the stuff SDFB is made of, and the project could not realistically provide it and still offer 200,000 relationships upon initial public release. In many cases such details will not be missed in the high altitude views provided by SDFB’s network maps, but it is important to recognize what the site cannot do as well as what it can. For example, anyone who hoped to track Harvey’s shifting connections with friends and enemies from, say, the 1570s to the 1580s will be disappointed; while the basic model of SDFB could, in principle, represent those shifts, the data presently available are simply not that detailed.

We run into another gap in the data if we try to reproduce the association of Christopher Marlowe with the Muscovy Company mentioned earlier; a group search on the Muscovy Company reveals no one in Marlowe’s network and turns up only two members of the Company, a result so incomplete that opportunity knocks. A supervised undergraduate or educated member of the general public could, with careful use of reliable secondary sources, make a significant contribution that fills in this gap.

Further exploration of Marlowe’s network reveals some sins of commission as well as of omission. SDFB until recently listed the “Lord Admiral’s Men,” of which Marlowe was a member, as a “theatrical company established by Henry Carey, Baron Hunsdon,” with a start date of 1594. This description and start date obviously belong not to the Admiral’s Men but to Shakespeare’s company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men.[6] It must be said that, with the theaters closed for plague in 1593, almost any Elizabethan company of players could be said to have re-started in 1594, but nevertheless there is a gremlin in these data. Christopher Marlowe’s membership in the Lord Admiral’s Men is, in the “more information” view, shown to start in 1594 (the year after he died) and, in the search view, the scarcely more probable 1564, the year of his birth. A bit more study of this and other groups reveals numerous cases where the “Membership Start Date” is the year of a member’s birth in search results, even if the member was born well before the group started, and in Marlowe’s case, the error in the founding year of the Lord Admiral’s Men makes it appear that he joined the group the year after he left it via death.

The error is rare but not unique. For example, a group called the Cabal, started in 1667, lists as a member one Oliver Cromwell, who died in 1658. One need not hold an endowed chair in seventeenth-century political history to realize that the dates are not the only problem here. The five members of Charles II’s inner circle of advisers (whose names spell out C-A-B-A-L), would surely not have welcomed Cromwell into their company, though they would have known who he was and perhaps been in a sense part of his social network. It is easy to infer what likely happened. An automated or semi-automated process to deduce group memberships from ODNB entries surely found many mentions of Cromwell’s name in the biographies of influential persons in the Restoration monarchy and extrapolated from a web of connections to group membership. Or, it could have been a good old-fashioned data entry error. Either way, the project would do well to develop automated testing procedures that can flush out similar impossibilities.

Such a deep dive into the data shows the lure of SDFB as well as its pitfalls. Humanists who are not accustomed to working with data may be tempted to rely exclusively on the visually stunning network graphs, but they would do well to take advantage of the various materials provided for deepening their understanding of what the site is, how it can be used, and opportunities to improve and extend it. Data (at least some of them) are available under an open access license.[7] There are tutorials (both video and text), teaching guides, a blog with several usage examples, and a help page consisting of some two dozen frequently asked questions and their answers. There is also a Twitter feed (@6Bacon) with over a thousand followers. Start networking.

Craig A. Berry

Independent Scholar

[1] Michael Murrin, Trade and Romance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014) 201.

[2] See Evelina Gabasova, “The Star Wars Social Network,” <http://evelinag.com/blog/2015/12-15-star-wars-social-network/index.html#.Vpq3JjYshdQ>, and Martin Grandjean, “Network Visualization: Mapping Shakespeare’s Tragedies,” <http://www.martingrandjean.ch/network-visualization-shakespeare/>.

[3] Scott Weingart and Jessica Otis, “Gender Inclusivity in Six Degrees,” <http://6dfb.tumblr.com/post/136678327006/gender-inclusivity-in-six-degrees>.

[4] “Networking Women,” <http://networkingwomen.sixdegreesoffrancisbacon.com>.

[6] I discovered and reported the error on December 20, 2015. As of January 16, 2016, the patronage of the group has been corrected to “Charles Howard, Baron Howard of Effingham,” but the start year is still recorded as 1594.

[7] The structure of the database is documented at <http://sixdegreesoffrancisbacon.com/assets/SDFB_ERD_12-10-15-93d1455d51a644883c29c9a17d45e56d3d4196701035d6ff779b4b316e8d664b.pdf>, but that diagram contains many elements that are not present in the simplified data sets downloadable via the site’s View Records links. Also, the software behind the SDFB data mining, statistical model, and web site is not open source in the current beta version.

45.3.18

Comments

May I enquire why this potentially useful resource is named after Francis Bacon?

Link / ReplyYou may indeed! If you Google the phrase "six degrees of Kevin Bacon," I believe you will have your answer.

Link / ReplyI have done as you suggested and am duly enlightened, with thanks. I remember when I was working on the claim that Shakespeare was the author of *A Funerall Elegye for William Peter* 1612 (in fact written by John Ford), and one of its advocates had tried to show that Shakespeare was indirectly related to the deceased's family, a historian colleague said "if you go on long enough in early modern England you can show that everyone is related".

Link / ReplyMy salutations to Craig Berry, a hero of mine for his achievement in programming the wonderful Chicago Homer, one of the best interactive scholarly reources on the web. See http://homer.library.northwestern.edu/

Link / ReplyGreetings to you as well, Brian, and thanks for your kind words about the Chicago Homer.

Link / ReplyIn addition to the Kevin Bacon reference, I suspect Francis Bacon was chosen because he knew lots of people and offers as good a place to start as any for exploring the early modern social network.

The analysis of social networks has long been familiar to social scientists, and for that matter is hardly new elsewhere.

Link / ReplyAll you need do is schedule when you’d like us to drop by.

Link / ReplyYou must log in to comment.