Early Modern Print: Text Mining Early Printed English. Joseph Loewenstein, Anupam Basu, Doug Knox, and Stephen Pentecost, http://earlyprint.wustl.edu.

The Stanford Literary Lab recently released an eleventh pamphlet that asks, “have the digital skies revealed anything that changes our knowledge of literature?”[1] This is the fundamental question needing answers in most digital humanities projects focusing on large corpora. One of the reasons that answers have been in short supply is that most researchers and teachers do not have ready access to the tools needed to answer their scholarly questions.

Early Modern Print (hereafter referred to as Early Print) has the potential to change that. Early Print offers two web-based tools to assist scholars with text mining in early printed English. Using the Early English Books Online and the Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership (EEBO-TCP) corpus, readers wanting more specific insight into EEBO-TCP can refer to a concise and helpful overview provided by Joseph Loewenstein or to the official EEBO site. This information helps to place the corpus in context and address the limitations of the tools. However, Early Print show tremendous promise as a suite of open-access tools to assist researchers hoping to gain new knowledge about literature.

Early Print started as a way to solve some of the analytic problems associated with an online edition of the forthcoming Collected Works of Edmund Spenser for Oxford University Press. The project is housed at Washington University in St. Louis under the direction of Joseph Loewenstein. As explained on the site, Loewenstein “hoped to confer greater precision on the long-standing general assessment of the archaism of Spenser’s language,” and wondered “how we might measure the orthographic and lexical temporality, the conservatism and innovation of any given work or corpus against the larger tendencies of the print record.”

Anupum Basu, Weil Fellow in Digital Humanities at Washington University in St. Louis, set out to answer these concerns from a technical perspective, and he is the programming mind behind the tools. One of the most useful aspects of the tools is their ability to bypass the oddities of early modern print. In other words, Basu was able to write a program that overcomes the irregularities of the both the language use (e.g., spellings, thorns, etc.) and the print process. The result is a pair of tools that are highly useful and practical for the Early Modern researcher and teacher.

While Early Print does not provide an interface to the full texts, the technical capabilities of the tools allow researchers to the see the “aggregate view of the corpus that enables us to probe English lexical and orthographic history that usefully complement the search capabilities of EEBO-TCP.” In other words, the tools provided supplement other means of research and analysis that early modern scholars are already using. This added layer, however, not only enriches our understanding of book history of the era, it can provide important insights into shifting and changing ideas through historical tracing of words and phrases and, more importantly, words and phrases in context.

Overview of the Tools

N-gram Browser

An n-gram is a common text mining technique where the “N” represents a number of words or phrases larger than zero that will be used in the analysis. In the simplest terms, an n-gram browser lets you trace the popularity of words or phrases over a period of time. What was once only in the purview of computer scientists and computational linguistics, Google Books brought n-grams to the wider public. Early Print’s n-gram browser functions in much the same way as Google Books. You simply insert the word or phrase you would like to track, select the years, and voila! N-grams are complex computational schemes and the Early Print tool allows advanced users to select between uni-, bi-, and even tri-grams, which will increase the possibilities of how the results can provide insights into the both the works and the culture of the time. Below is the n-gram for my selected term of “healthe.”

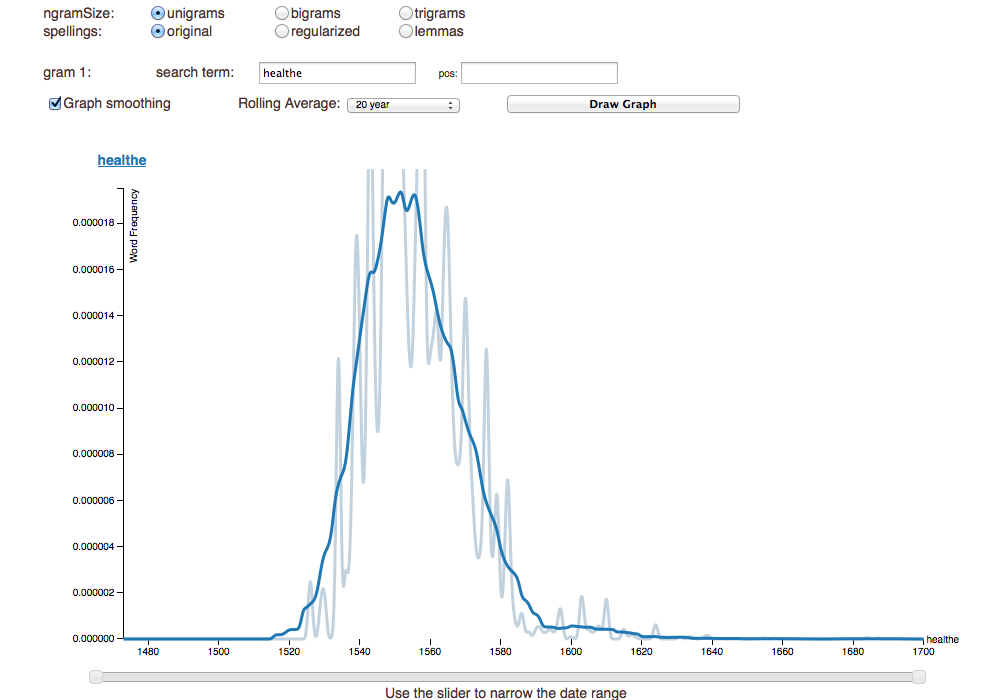

Figure 1: Results of the n-gram browser tool.

For a researcher or teacher who works in the Early Modern era, the n-gram shows the spike of “healthe” during the time that I would most expect it, which is in the early days of vernacular print when large numbers of books were printed for everyday people. Users with knowledge of the era can glean information from the n-gram results that previously was not possible without extensive and intensive manual coding of texts. For example, while the results for my query were not surprising, I now have a more precise point of popularity and decline, which adds an additional layer of credibility to my arguments around health and medicine. Basu provides detailed instructions for the tool that allow new users to start within a few minutes and understand what the results actually mean.

Key words in context allows you to search by

- single term: a single word

- wildcard: use of an asterisk to represent characters or a ? for one character. E.g, s*nesses will provide all results of the varying spellings for sicknesses as well as sweetnesses, sharpenesses and others.

- “fuzzy,”: word or phrase followed by a tilde and a number to find words that are similar to your term or phrase

- multi-word: place words in quotation marks to find the complete phraseproximity serarchespro

- prommmrProximity: words or phrases in quotation marks followed by a tilde and a number will produce your selected words in context within the distance you specified. E.g., “for headache”~2 will find all instances of “for and “headache” within two words of one another.

You can also limit the year range and search by author or title. The results list will provide a link to the EEBO-TCP, the year of publication, the author, book title, and then the sentence in which your search term appears. By clicking on the link to the EEBO-TCP, you can see the publication information and have the option of viewing the full text. (You can also access the text and metadata directly through EEBO.) An additional important feature of this tool is the ability to choose from three different types of spelling choice (regularized, original, and lemmatized, which is grouping words by variant forms).

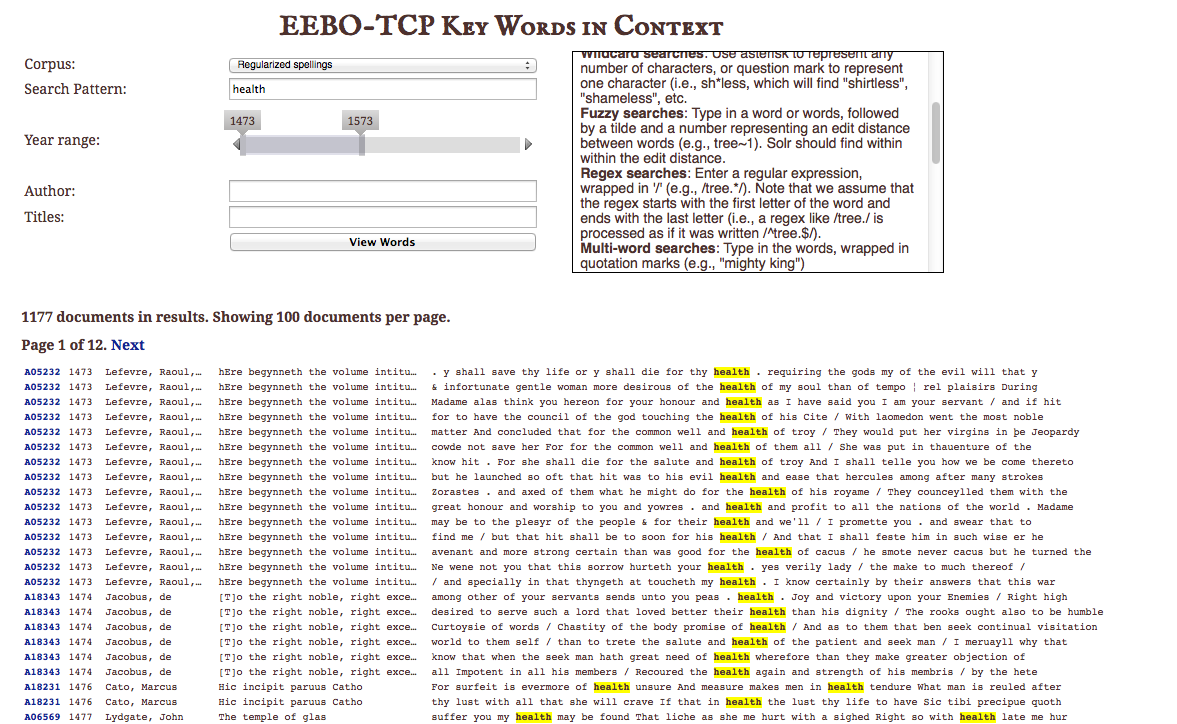

Figure 2: Results of the word in content tool

Here is the perfect time for me to fully disclose. While I am an Early Modernist, I am not a literary scholar. My primary fields are rhetoric and technical communication, and as someone who teaches people how to create and improve tools like this one, I have to say the interface is intuitive and when you need help, the site provides useful information on how to manage the tools, which increases their value for a larger audience of researchers and teachers.

How can researchers and teachers use this tool?

While information on the Early Print page suggests that the “tool most likely to claim an afternoon’s attention is the n-gram browser,” I would counter that the most powerful tool developed is the key words in context tool.

Being able to find words and phrases in text and then see them in context helps to offset some of the criticisms of “big data” and the early criticisms of tools such as n-gram viewers. Seeing the word in context is highly important when doing research on somewhat common subjects, and yet, you still need to track its use over time. For example, one word important to my own research is “health.” However, I am not at all concerned about “health” in any other context than directly related to the physical state of a person. Thus, references to “health” that are metaphorical or referencing the state are not useful for my project. Further, the way the context tool displays information makes determining the context super simple, and if it’s a reference for which you need to read more than the snippet provided, it displays the link to go to the full text. This particular aspect of Early Print has saved me hours of research.

One can use the n-gram viewer to generate large scale views of a particular term and then narrow that down with the context tool. These results can then be added to other forms of analysis, and going back to the original question that started this review, the answer would be, yes: the “digital skies” have shown us more about literature than we knew before. In my case, I was able more accurately to see changes in and standardizations of health and medical terms with the n-gram browser. Being able to limit the years and see the results is useful. For example, “headache” is a much more common term over time than is “migraine.” However, one must know what an n-gram is and how or why it could be used effectively for a research question for this tool to be of benefit.

In teaching practices, there is much to be gained from using Early Modern Print as a supplement to a wide variety of courses (think Book History, History of Media, Research Methods, and topics and surveys of research in the early modern period). The next time I teach a research methods course I will definitely be using the site. Considering corpus-scale analysis as another way to uncover trends in texts offers opportunities for students to not only learn about the Early Modern era but also to engage other scholarly questions currently facing Early Modernists, digital humanists, book historians, and others. For example, the tools provide an accessible way to discuss complex topics about the reliability of big data, the limits and affordances of digital tools, general concepts about research study design and limitations of such design, and most importantly, using multiple methods and approaches to answer your question.

Moreover, Early Print provides a different meta-history of the books in the corpora, and more importantly, these tools shed light on the texts we choose to study. For example, the small, octavo vernacular medical texts I study have been studied, but they are usually used as a means to explore Early Modern literature and to gain a better cultural understanding of the pervasiveness of medical terminology, analogy, and metaphor in the texts of the era. Few scholars have actually studied them in their own right. It could be that their scholarly exploration has been limited because of access, but with large-scale digitization projects and tools such as these, scholars now have the opportunity to not only study less known works, but to explore them in new ways.

Early Print’s suite of tools affords scholars of the Early Modern era—no matter what your disciplinary home might be—the ability to examine large-scale digital humanities projects without needing digital humanities equipment and specialized knowledge. This is a great gift for cash-strapped faculty working at smaller institutions that may not have the technologies available to do this type of work on their own. Moreover, it enables time-strapped faculty the ability to do serious, scholarly criticism without having to learn a whole host of new programs or skills. Please note I am an advocate of learning new tools and technologies and believe that learning some of the “back-end” of how these technologies work is good. I teach courses that could lead people to building the exact types of tools created. However, even someone with my level of technical expertise desperately needed these tools. Why? Because I would still have to track down the technologies on campus, arrange days and times (on someone else’s schedule most likely), and then do refresher courses to remind myself how to do things. On the other hand, I took the keyword in context tool, plugged in my word, and voila! In less than a minute, I had the data in front of me that would have taken me hours if not days to produce on my own. There is an educational and research power in that and one that leads to new discoveries of the “big skies” at faster rates.

Finally, as Loewenstein points out, the same caveats and limitations that apply to corpus of EEBO and EECO-TCP remain. In addition, as the Stanford group affirms, there is an inherent bias in any archive which needs to be accounted for when doing the final analysis and explanation of the data.

Looking to the Future

The text on the homepage states the site and its tools are more of a provocation to encourage scholars to envision their own questions and projects in new ways. I like this idea of provocation, and I would take up Early Print’s challenge and simultaneously offer one of my own.

In taking up Early Print’s challenge, I have managed to see my own project in new ways. For example, I have gathered a number of key recipes from manuscripts and have traced them through the later medieval era until the early seventeenth century. The Early Print tools have allowed me to see some of the key terms and phrases differently by how often they have appeared and in what context. The continuation of certain recipes, such as those for the migra(y)ine (modern version = migraine), without major changes in close to two hundred years raises the types of questions scholars need to be raising about knowledge creation and circulation. I do not have answers as of yet, but some of my questions would not have been possible without the Early Print tools.

Additionally, one of the major problems with many of the digital humanities projects is that they are not scalable. In other words, they do a fine job at the project and task at hand, but they lack the ability to move forward, backward or sideways. I wonder if Early Print’s technical framework could be scaled and ported so that other corpora from this era could be included and analyzed the same way. For example, there is a growing corpus of digital letters and manuscripts around the world. Could these corpora take care to do some preliminary OCR work (making the text readable for the software) so that the Early Print technical framework could be used? It is this type of collaboration between digital projects and initiatives that is missing in much of the digital humanities work being done, but it is collaboration that will ultimately answer the big questions about literature in the “digital skies.”

Lisa Meloncon

University of Cincinnati

[1]Mark Algee-Hewitt, et al., “Canon/Archive.Large-Scale Dynamics in the Literary Field,” LitLab, Stanford University, 2016, vol. 11, pp. 1-14, http://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet11.pdf.

46.1.16

Comments

Early Modern Print refers to the period between the invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century and the end of the 18th century. Text Mining Early Printed English involves using computational techniques to analyze large collections of texts from this period, such as those available through https://www.google.com/ Books. This allows researchers to study patterns and trends in language use, as well as explore how certain topics were discussed and represented in the past. Such analyses can provide valuable insights into historical and cultural contexts and help us better understand the evolution of language and society.

Link / ReplyHowever, Early Print show tremendous promise as a suite of open-access tools to assist researchers hoping to gain new knowledge about literature.

Link / ReplyGreetings! It is often incredible to observe how technology can turn sour perspectives to historical texts into pro-vantageous ones, letting us see nuances and patterns that were hidden because of an enormous pile of material or limitations of traditional methods. Personally, in the process of historical documents and literary works, I found working with and organizing digital copies extremely difficult. That's where I came upon https://pdfguru.com/ , a resource that has been really useful in my study was. Whether it is OCR of digital documents to text, or annotating texts, PDF Guru has simplified the whole thing to the extent that everything is now smooth and short-lived.

Link / ReplyThank you for this information. It is quite tough to succeed in all subjects in university, especially when you are working in parallel. As a result, I discovered https://99papers.com/ . It suits me because everyone here is an expert in their industry. They know how to write well. The essential point is that they accomplish it swiftly and cheaply.

Link / ReplyEncouraging users to create and share content related to a brand can increase engagement and authenticity. UGC campaigns, such as social media challenges and reviews, can be highly effective in building a community around a brand. https://nongamstopcasinos.ltd/

Link / ReplyOne of the reasons that answers have been in short supply is that most researchers and teachers do not have ready access to the tools needed to answer their scholarly questions.

Link / ReplyYou must log in to comment.