Goth, Maik. Monsters and the Poetic Imagination in The Faerie Queene: ‘Most ugly shapes, and horrible aspects.’ Manchester UP, 2015. viii + 365 pp. ISBN: 978-0719095719. $105.00 cloth.

Pedersen, Tara. Mermaids and the Production of Knowledge in Early Modern England. Ashgate P, 2015. x + 155 pp. ISBN: 978-1472440013. $100.00 cloth.

Maik Goth’s stated aim is “a comprehensive reading of monsters and monstrous beings” throughout the whole of The Faerie Queene. Parts I and II of this ambitious, innovative contribution to Spenser studies place The Faerie Queene’s monsters in the context of teratological, historical, and literary perspectives on the monstrous, and offer a valuable taxonomic account under six headings: dragons, four-footed beasts, human-animal composites, giants, monstrous humans, and automata. Part III analyzes their relevance to Early Modern discourse on poetic creation and advances Goth’s illuminating theory of Spenser as Prometheus. The volume is rounded off with a brief conclusion (Part IV), substantial bibliographies of primary and secondary sources, and a scholarly index. Tara Pedersen’s monograph brings together four chapters and an afterword, consecutively discussing, in relation to a single type of monster (mermaids), Thomas Dekker and Thomas Middleton’s The Roaring Girl, Margaret Cavendish’s The Convent of Pleasure, The Faerie Queene (chapter 3: “Perfect Pictures: the Mermaid’s Half-theater and the Anti-theatrical Debates in Book II of Spenser’s The Faerie Queene”), Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra, and Hamlet. Literary monsters, central to Goth’s argument, but pushed to the margins of Pedersen’s discussion of The Faerie Queene, which foregrounds “the text itself as mermaid” (82), inform their shared theme. Both identify Spenser as a writer whose reactions to ongoing cultural trends shaped his poetry, and privilege the monstrous as a major key to placing his creative output in relation to Early Modern literary theory, as expressed in George Puttenham’s Arte of English Poesie of 1589 and Philip Sidney’s Defence of Poesy of 1595 (Goth), and Stephen Gosson’s Playes Confuted in Fiue Actions of 1582 and School of Abuse of 1579 (Pedersen).

A great strength of Goth’s study is its multiple appeal. This weighty contribution to literary studies will interest historians of fantasy, horror and the grotesque, of disability and of teratology, as well as specialists in Spenser, the literary debates of his time, or monsters in fiction. Supporting his text with a wealth of notes, identifying many unexpected contributions and references as well as most of the usual suspects, Goth reliably signposts the complex range of English and European monster traditions, myths and texts, raided, paraded, and upgraded by Spenser for his monsters. Chapters 1 and 2 situate The Faerie Queene as “a poem of monsters” and survey the premodern concept of the monster. Chapters 3 and 4 consider major trends in Early Modern monster studies, Spenserian scholarship on monsters, and the gap opening up between them. Arguably, in this section and in the volume as a whole, more attention could have been paid to the strongly emerging field of premodern disability studies,[1] and several categories of Spenserian monster are under-represented. While giants are bigged up,[2] dwarfs (another Arthurian staple) and fairies get short shrift. The four dwarfs who serve noble brides in The Faerie Queene, Florimell’s Dony and the unnamed dwarfs of Una, Paeana and Briana, are hardly noted. Despite the pivotal role of the Wild Man in one of Spenser’s fundamental sources, European chivalric romance, Goth refers only in passing to The Faerie Queene’s Wild Men, and not at all to the potential for upping their number from the four identified by traditional Spenserian scholarship (Arthur’s Salvage Man, Lust, Timias, Artegall) to nearly twenty.[3] Rather than foregrounding generic monstrous types, borrowed with little or no modification from specific cultural or anatomical precedents, Goth’s main focus is on Spenser’s own, uniquely named and assembled monsters.

This approach underlies Part II, whose taxonomic considerations, the core of this book, are complemented by twelve well-chosen reproductions. Chapter 5 provides a general overview; the following two, both on “Monstrous Animals,” respectively focus on dragons (in Eden, that of Orgoglio then Duessa, Geryoneo’s, and in fights),[4] and on the pseudo-hyena conjured up by the witch of III.vii, and The Blatant Beast, this latter treated to a fine and full analysis. Chapter 8, on “Human-animal composites,” brings together the serpentine Errour (yet another dragon of sorts), Spenser’s mermaids and sirens (briefly but deftly discussed here, rather than with the sea monsters of chapter 10), and Duessa. “Giants” (chapter 9) bookends sections on the Albion Giants, Orgoglio, Lust, and the twins Argante and Ollyphant, between an overview of Spenserian giants and a brief tailpiece on The Faerie Queene’s gigantic humans. Chapter 10, “Monstrous humans,” first considers, in the light of the classical monstrous races, Una’s satyrs and Satyrane[5] and the “Amazonian” Radigund (but not Belphoebe), then “Carles and hags,” notably Maleger[6] and Ate. Detailed discussions of various categories and examples of transformed and metamorphosed humans include the tree-man Fradubio, sea monsters, the hog Gryll, Adicia (the evil queen metamorphosed into a tiger during a fit of rage—but not, despite Spenser’s repeated Ovidian references to her, Medusa), the Seven Deadly Sins, and an insightful consideration of satyrs in the Malbecco and Hellenore episode (confusingly unindexed and separated from the chapter’s opening discussion of Satyrane). Finishing with a valiant attempt to pin down the elusive Spenserian phenomenon of “Ephemeral Monstrosity,” this shaggy monster of a chapter contains much of great value. Chapter 11, “Automata,” examines “a triad of singularly important mechanical creatures”: Talus, Disdayne, and at fascinating length, Spenser’s demonically repellent False Florimell. Here as throughout, Goth deploys his thorough familiarity with historical precedents to contextualize individual discussions of Spenser’s monsters to great effect.

Part III focuses on Spenser’s use of monsters as a vehicle for drawing his readers into allegorical interpretation, and comprehensively revisits one of his most complex creations, Alma’s Castle and its tripartite brain turret, with reference to Timothy Bright’s Treatise of Melancholie, Robert Burton’s Anatomie of Melancholie, and other contemporary medical and philosophical discourse relevant to the poetic imagination. The partial, overlapping, and anatomically incoherent taxonomy underlying Part II is largely unavoidable, given that no approach to classifying The Faerie Queene’s monsters, cultural or scientific, can avoid being trumped by Spenser’s slippery, shape-shifting fecundity. In the light of Sidney’s declaration that the poet, “lifted up with the vigour of his own invention, doth grow in effect another nature […] Heroes, Demigods, Cyclops, Chimeras, Furies and such like,” Part III then identifies Spenser’s view of his poetic creativity with the literary creation of new, unnatural, monstrous life-forms. Central to Goth’s thesis is the paradoxical dual nature of literary monsters, as negative, disgusting zoological and hybrid composites which are simultaneously also radical but admirable cultural products of the poetic imagination: nothing less than Spenser’s own Promethean creations (316). Goth here draws on recent scholarship, including detailed responses from several renowned Spenserians to his 2009 article on Spenser as Prometheus, to valuably inform and develop an argument refined over many years.[7]

Pedersen’s book is too short to accommodate Goth’s multiple approach. Written neither for teratologists nor Spenser specialists, it is not an authoritative contribution to mermaid studies, but a case-study based examination of theatrical culture and its shifting status in Early Modern England in the light of some current areas of concern in literary studies. The introductory overview of Early Modern mermaids is necessarily brief and selective. The nine black and white figures, albeit only superficially documented in the captions or text, are a welcome bonus, and the volume’s usefulness might have been further enhanced by a greater reliance on fundamental scholarship (see Goth 2015, 92-3) and primary sources for pre-modern merfolk. My own reading of these suggests that mermaids were hardly less fabulous in the Early Modern period than they are now; and that Early Modern records of sightings are not “numerous” (28), are only exceptionally first hand, and are often received with a healthy dose of skepticism.[8] Two by English explorers are quoted, Henry Hudson’s account of 15 June 1608 from a modern secondary source, and a report of a mermaid sighting here attributed to John Smith in 1614.[9] Perhaps a garbled misinterpretation of Captain Richard Whitbourne’s account of the mermaid-like “strange creature” he saw off the coast of Newfoundland in 1610, the immediate source for the quoted account of Smith’s alleged sighting is not a seventeenth-century historical document, but the unattributed English translation, published in 1849, of a fictional adventure story written in French by Alexandre Dumas.[10] Its introductory anecdote about merfolk includes a verbatim match for Pedersen’s anachronistic unreferenced quote.[11]

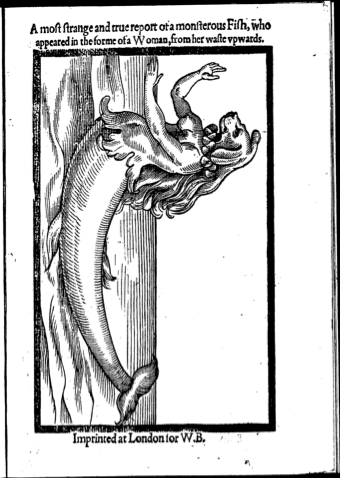

P.G., A most strange and true report of a monsterous fish,

1604, frontispiece

Although not discussed, British sightings, especially those circulated in cheap print, arguably impacted on London theatre culture at least as profoundly as those by overseas explorers, often reported only years after the actual event. Perhaps the most dramatic was the fish-woman witnessed by over a dozen Welshmen off the Carmarthen coast at Pendine in 1603. Their detailed report was quickly published in an eight-page pamphlet.[12]Mentioning neither mermaids nor syrens, it depicts this “monsterous Fish, that appeared in the forme of a Woman, from her wast vpwardes” as a seal-like creature with an impressively full head of hair, and human breasts, arms and hands (see plate), in effect an amiable, domesticated version of the terrifying Sea Devil depicted by Ulisse Aldrovandi (reproduced: Goth 148, fig.12). Pedersen’s mermaid metaphor is at best fragile. Why privilege mermaids as opposed to centaurs, Wild Women, hermaphrodites, satyrs or harpies? And should we accept that the Early Modern mermaid’s identity is profoundly incoherent (8)? Or factor in the views of those, such as John Locke, who suggest otherwise?[13]

Proposing Book II of The Faerie Queene as “one of the most sustained and unexpected meditations on the relationship between stage and page within the early modern period […] an unusual defense of hybrid, mermaid-like, genres of art and the breaking down of social distinctions” (83), Pedersen’s third chapter promotes the startling view that mermaids are “deeply embedded in one of the most heated artistic debates of the period.” This anti-theatrical debate provides her chosen context for examining Spenser’s poetry. Comprehensive reference to these debates informs her discussion of Spenser’s account of Guyon’s Odyssean voyage to the Bower of Bliss, which prominently features mermaids, (II.xii.17 and 30), and of the Bower episode itself. The stanzas describing the naked “damzelles” sporting in the Bower’s lake, whose “snowy limbes, as through a vele / So through the Christall waues appeared plaine,” yield insubstantial support for Pedersen’s confident linking of these two “wanton Maidens” with mermaids (II.xii.63-68). And how relevant to the centrality of the mermaid is a passage in which Gosson warns against the theatre’s ability to corrupt youth, by its “mixture of good and eull […] mingle ma[n]gle of fish & flesh, good & bad”?[14] Could Gosson here primarily be evoking not the monstrous, anatomically hybrid conjoinment of merfolk, but a possibility unacknowledged by Pedersen, namely the religious, culinary opposition of serious, fasting Lent and foolish, feasting Carnival? On the other hand, might not her argument have gained by reference to the third of Sidney’s “most important imputations laid to the poore Poets […] that it is the nurse of abuse, infecting vs with many pestilent desires, with a Sirens sweetnesse, drawing the minde to the Serpents taile of sinfull fansies”?[15] Or to Spenser’s siren-like serpent-woman Errour, or Florimell, covered with fish scales after her assault by a fisherman, both discussed in satisfying detail by Goth (168)? Inspiring sirens or red herrings? Whatever your take on Pedersen’s mermaids, she is to be congratulated for her insightful, even controversial, analysis of key texts in the light of Early Modern discourses on anti-theatricality, gender and identity. Her imaginative book offers richly stimulating discussion points for specialists and students of The Faerie Queene and the drama of its time.

These two books, each based on a doctoral thesis, exemplify the increasingly significant incompatibilities opening up between expectations for the outcomes of leading postgraduate literary researches in Germany and the US. Authored by one of the final cohort of early modernists guided to publication at Ashgate Press by the gentle genius of Erika Gaffney, Pedersen’s fresh, provocative monograph is engagingly on trend and of the moment. Goth’s substantial contribution to Julian Lethbridge’s prestigious series, The Manchester Spenser, represents a solidly crafted resource for all serious Spenserians, the authoritative text in its field for years to come.

M A Katritzky

The Open University

[1] Notably, in the context of Spenserian scholarship: Allison P. Hobgood and David Houston Wood, eds., Recovering Disability in Early Modern England, Ohio State UP, 2013, two of whose ten chapters focus on Spenser: chapter 1, Sara van den Berg, “Dwarf Aesthetics in Spenser’s Faerie Queene and the Early Modern Court,” pp. 22-53, and chapter 5, Rachel E. Hile, “Disabling Allegories in Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene,” pp. 88-104.

[2] See also Susanne Lindgren Wofford, “Spenser’s Giants,” in Critical Essays on Edmund Spenser, ed. Mihoko Suzuki, G.K. Hall, 1996, pp. 199-220.

[3] Benjamin Myers, “‘Such is the face of falshood’: Spenserian Theodicy in Ireland,” Studies in Philology, vol. 103, no. 4, 2006, pp. 383-416.

[4] See also Kenneth Hodges, “Reformed Dragons: Bevis of Hampton, Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur, and Spenser’s Faerie Queene,” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 54, no. 1, 2012, pp. 110-131.

[5] See also Kathryn Walls, God’s Only Daughter: Spenser’s Una as the Invisible Church, Manchester UP, 2013.

[6] See also Judith H. Anderson, “Body of Death: The Pauline Inheritance in Donne’s Sermons, Spenser’s Maleger, and Milton’s Sin and Death,” in Rhetorics of Bodily Disease and Health in Medieval and Early Modern England, edited by Jennifer C. Vaught, Ashgate, 2010, pp. 171-192.

[7] Maik Goth, “Spenser as Prometheus: The Monstrous and the Idea of Poetic Creation,” Connotations, vol. 18, no. 1-3, 2008/2009, pp. 183-207, Andrew Hadfield, “Spenser as Prometheus: A Response to Maik Goth,” Connotations, vol. 20, no. 2-3, 2010/2011, pp. 189-200, John Watkins, “Spenser’s Monsters: A Response to Maik Goth,” Connotations, vol. 20, no. 2-3, 2010/2011, pp. 201-209, Matthew Woodcock, “Elf-Fashioning Revisited: A Response to Maik Goth,” Connotations, vol. 20, no. 2-3, 2010/2011, pp. 210-220, Maurice Hunt, “Spenser’s Monsters: A Response to Maik Goth and to John Watkins,” Connotations, vol. 21, no. 1, 2011/2012, pp. 1-7.

[8] Antonio de Torquemada, The Spanish Mandeuile of Miracles (1600), sig.33v: “there is indeede much talke of the Mermaydes, whom they say from the middle vpward to haue the shape of women, and of a fish from thence downeward… . but to say the truth, I haue neuer seen any Author worthy of credit, that maketh mention hereof. … And though it may be that there is in the Sea such a kind of fish, yet I account … them to be a meer fable.”

[9] See Samuel Purchas, Purchas His Pilgrimes in Five Bookes, Henrie Fetherstone, 1625, vol. III, Chapter 15: “A second voyage or employment of Master Henry Hvdson, for finding a passage to the East Indies by the North-East: written by himselfe,” p. 575; and vol. IV, Chapter 8: “Captain Richard Whitbovrnes Voyages to New-found-land, and obseruations there, and thereof, taken out of his Printed Books,” pp. 1887-1888.

[10] See Vaughn Scribner, “Fabricating History: The Curious Case of John Smith, a Green-Haired Mermaid, and Alexandre Dumas,” 16 June 2015, online, accessed 2 Feb. 2016, earlyamericanists.com/2015/06/16/guest-post-from-vaughn-scribner-fabricating-history-the-curious-case-of-john-smith-a-green-haired-mermaid-and-alexandre-dumas/ and “Fabricating History PART TWO: The Curious Case Continues,” 2 July 2015, online, accessed 2 Feb. 2016, earlyamericanists.com/2015/07/02/fabricating-history-part-two-the-curious-case-continues/.

[11] Alexandre Dumas, “Nuptials of Father Polypus,” The Gazette of the Union, vol. 11, no. 13, 1849, Crampton and Clarke, p. 200: “Captain John Smith, an Englishman, saw in 1611, off an island in the West Indies, a syren, with the upper part of the body perfectly resembling a woman. She was swimming about with all possible grace, when he descried her near the shore. Her large eyes, rather too round, her finely shaped nose, somewhat short, it is true, her well-formed ears, rather too long however, made her a very agreeable person, and her long green hair imparted to her an original character by no means unattractive.”

[12] P.G., A most strange and true report of a monsterous fish, who appeared in the forme of a woman from her waste vpwards, seene in the Sea by divers men of good reputation on the 17 of February 1603 (W.B., [1604?]).

[13] John Locke, An essay concerning humane understanding, 1690, p. 196: “And though there neither were, nor had been in Nature such a Beast as an Unicorn, nor such a Fish as a Mermaid; yet supposing those Names to stand for complex abstract Ideas, that contained no inconsistency in them; the Essence of a Mermaid is as intelligible, as that of a Man; and the Idea of an Unicorn, as certain, steady, and permanent, as that of an Horse.”

[14] Stephen Gosson, Playes confuted in fiue actions, Thomas Gosson, 1582, sig.C7r.

[15] Phillip Sidney, The defence of poesie, William Ponsonby, 1595, sig.F4v.

46.1.6

Comments

Maik Goth's declared goal is to provide "a comprehensive reading of monsters and monstrous beings" throughout The Faerie Queene. Parts I and II of this ambitious, new contribution to Spenser studies examine the monsters of The Faerie Queene in the context of teratological, historical, and literary perspectives on the monstrous.

Link / ReplyBoth emphasize the monstrous as a significant factor in situating Spenser's creative production in relation to Early Modern literary theory and identify him as a writer whose responses to contemporary cultural changes impacted his poetry.

Link / ReplyGoth effectively uses his in-depth knowledge of historical precedents to contextualize specific debates of Spenser's creatures.

Link / ReplyA fascinating dialog is value remark. I feel that it is best to compose more on this matter, it may not be an unthinkable theme however generally people are insufficient to chat on such subjects. To the following.

Link / Replysimply couldn’t depart your site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the usual info a person provide for your guests?Is gonna be back incessantly to check up on new posts

Link / Replysimply couldn’t depart your site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the usual info a person provide for your guests?Is gonna be back incessantly to check up on new posts

Link / Replyarger businesses can manage and host internal events like all-hands and sales summits or external events like user conferences and consumer events and Zoom's biggest focus has always been large enterprises.

Link / ReplySurrounded by worries and stress? Your relief mantra is here! Crazy For Study brings optimum solutions to ease your academic burden. It’s cost effective, accredited and recommended by best brains worldwide! Bring wealth of knowledge at your home today, and get promising results!

Link / Replyhowdy there, i suppose your website can be having internet browser compatibility issues. Every time i test your blog in safari, it appears exceptional however, while opening in net explorer, it has some overlapping troubles. I virtually wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Aside from that, high-quality website! Spot on with this write-up, i definitely experience this website desires lots extra attention

Link / Replysimply couldn’t depart your site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the usual info a person provide for your guests?Is gonna be back incessantly to check up on new posts

Link / Replysimply couldn’t depart your site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the usual info a person provide for your guests?Is gonna be back incessantly to check up on new posts

Link / ReplyReally decent post. I just discovered your weblog and needed to say that I have truly delighted in searching your blog entries. After all I'll be subscribing to your food and I trust you compose again soon! This article was written by a real thinking writer. I agree many of the with the solid points made by the writer. I’ll be back.

Link / Replyhowdy there, i suppose your website can be having internet browser compatibility issues. Every time i test your blog in safari, it appears exceptional however, while opening in net explorer, it has some overlapping troubles. I virtually wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Aside from that, high-quality website! Spot on with this write-up, i definitely experience this website desires lots extra attention

Link / ReplyMay I just say what a comfort to discover someone who actually knows what they are talking about online. You definitely realize how to bring an issue to light and make it important. More people should look at this and understand this side of your story. I was surprised you’re not more popular because you certainly possess the gift.|

Link / ReplyReally decent post. I just discovered your weblog and needed to say that I have truly delighted in searching your blog entries. After all I'll be subscribing to your food and I trust you compose again soon! This article was written by a real thinking writer. I agree many of the with the solid points made by the writer. I’ll be back.

Link / ReplyNice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon every day. It will always be useful to read through articles from other authors and use a little something from other web sites. This site was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve found something that helped me. Appreciate it! After looking into a few of the blog posts on your website, I honestly like your technique of blogging

Link / ReplyNice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon every day. It will always be useful to read th

Link / ReplyNice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon every day. It will always be useful to read th

Link / Replywhat i do not comprehended is in all fact the manner you aren't simply considerably more very plenty desired than you may be at this moment. You're insightful. You notice alongside those strains basically regarding the matter of this situation, added me as i would love to assume trust it is whatever but a first-rate deal of fluctuated elements

Link / ReplyReally decent post. I just discovered your weblog and needed to say that I have truly delighted in searching your blog entries. After all I'll be subscribing to your food and I trust you compose again soon! This article was written by a real thinking writer. I agree many of the with the solid points made by the writer. I’ll be back.

Link / Replywhat i do not comprehended is in all fact the manner you aren't simply considerably more very plenty desired than you may be at this moment. You're insightful. You notice alongside those strains

Link / Replysimply couldn’t depart your site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the usual info a person provide for your guests?Is gonna be back incessantly to check up on new posts

Link / ReplyNice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon every day. It will always be useful to

Link / Replyarger businesses can manage and host internal events like all-hands and sales summits or external events like user conferences and consumer events and Zoom's biggest focus has always been large enterprises.

Link / ReplyThis is my first time visit to your blog and I am very interested in the articles that you serve. Provide enough knowledge for me. Thank you for sharing useful and don't forget, keep

Link / Replyhowdy there, i suppose your website can be having internet browser compatibility issues. Every time i test your blog in safari, it appears exceptional however, while opening in net explorer, it has some overlapping troubles. I virtually wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Aside from that, high-quality website! Spot on with this write-up, i definitely experience this website desires lots extra attention

Link / ReplyThanks for every other excellent post. The place else may just anybody get that kind of information in such an ideal method of writing?I have a presentation next week, and I’m at the search for such info

Link / ReplyI really appreciate for your efforts you to put in this article, this is very informative and helpful. I really enjoyed reading this blog.So grab

Link / ReplyBrilliant post! Your incorporation of practical tips and real-life examples adds substantial weight to your ideas. Your evident commitment

Link / ReplyBrilliant post! Your incorporation of practical tips and real-life examples adds substantial weight to your ideas. Your evident commitment

Link / Replysimply couldn’t depart your site prior to suggesting that I really enjoyed the usual info a person provide for your guests?Is gonna be back incessantly to check up on new posts

Link / ReplyI really appreciate for your efforts you to put in this article, this is very informative and helpful. I really enjoyed reading this blog.So grab a

Link / ReplyGreat article you shared here. Thanks for sharing this valuable article. If you are interested in learning how bathroom mirrors decorate your space Great site! I'm glad that I found U!

Link / ReplyThis is my first time visit to your blog and I am very interested in the articles that you serve. Provide enough knowledge for me. Thank you for sharing useful and don't forget, keep sharing useful infoSo grab a drink, roll the dice, and let’s get began! With an LLC, you will have to file paperwork with the Secretary of State (or different company) to type the organization.

Link / Replyit is extremely important and large to pick out to your goods from an extensive sort of holograms reachable in the market these days. Hologram stickers are one of the exceptional strategies, and it is going to be a useful technique to your business. I should search web sites with applicable facts on given subject matter and provide them to instructor our opinion and the object.

Link / ReplyMay I just say what a comfort to discover someone who actually knows what they are talking about online. You definitely realize how to bring an issue to light and make it important. More people should look at this and understand this side of your story. I was surprised you’re not more popular because you certainly possess the gift.|

Link / ReplyNice post. I was checking continuously this blog and I am impressed! Extremely useful info particularly the last part :) I care for such information much. I was seeking this particular info for a long time. Thank you and good luck. This is my first time i visit here. I found so many entertaining stuff in your blog, especially its discussion. From the tons of comments on your articles, I guess I am not the only one having all the leisure here! Keep up the good work.

Link / ReplyYou truly make it look so normal with your presentation anyway I find this have an effect to be truly something which I figure I would never comprehend. It has all the earmarks of being unreasonably obfuscated and unbelievably wide for me. I'm l

Link / Replyhigh-quality beat ! I would love to apprentice whilst you amend your internet web page, how can i subscribe for a blog website? The account aided me a appropriate deal. I had been tiny bit acquainted of this your broadcast furnished shiny clean concept. I discovered your weblog the usage of msn. This is an exceptionally properly written article. I’ll make certain to bookmark it and come returned to study extra of your beneficial information. Thanks for the submit.

Link / ReplyI am really impressed with your writing skills well with the layout for your weblog. Is that this a paid subject matter or did you modify it your self? Anyway stay up the nice high quality writing, it is rare to see a nice weblog like this one these days

Link / ReplyHello! I know this is sort of off-topic but I had to ask. Does operating a well-established blog like yours require a large amount of work? I am completely new to writing a blog however I do write in my diary on a daily basis

Link / ReplyWow, What a Excellent post. I really found this to much informatics. It is what i was searching for.I would like to suggest you that please keep sharing such type of info.So grab a drink, roll the dice, and let’s get began! With an LLC, you will have to file paperwork with the Secretary of State (or different company) to type the organization.Thanks

Link / ReplyTook me time to read all the comments, but I really enjoyed the article. It proved to be Very helpful to me and I am sure to all the commenters here! It’s always nice when you can not only be informed, but also entertained

Link / Replyhttps://www.google.com <a href="https://www.google.com">href</a> [url=www.google.com]BB code[/url] google

Link / Reply<a href="https://www.google.com">href</a> [url=www.google.com]BB code[/url] google

Link / ReplyAs a seasoned Dietician with over 7 years of dedicated experience, I am passionate about cultivating the well-being of both mothers and children. In the realm of nutrition, I firmly believe that what we feed our bodies today shapes the resilient future of our families. Through my extensive journey, I have witnessed the transformative power of nutrition, and I am committed to sharing this wisdom with you.Navigating through the diverse pages of my website at Success Stories, you'll discover inspiring tales of individuals who have embraced a healthier lifestyle under my guidance. These stories serve as testaments to the impactful changes that proper nutrition can bring to one's life.

Link / ReplyHey there! I was fascinated by Maik Goth's exploration of monsters and the poetic imagination in The Faerie Queene, as well as Tara Pedersen's intriguing take on mermaids and the production of knowledge in early modern England. The depth of analysis in these works resonates with the precision and expertise that Advocate Prateek Singhania brings to the legal field through Legal Cloud.

Link / ReplyLegal Cloud, under the esteemed leadership of Advocate Prateek Singhania, is a testament to trust and professionalism in the legal domain. With over 8 years of rich legacy, Advocate Singhania brings profound insights into the intricacies of the law. Legal Cloud specializes in providing top-notch legal consultant services, ensuring clients receive comprehensive support and guidance.

If you're considering company incorporation, I highly recommend checking out Legal Cloud's expertise in this area. Their commitment to excellence and a thorough understanding of legal intricacies make them a reliable partner in navigating the complexities of company registration. You can explore more about their services and the process of company incorporation on their company registration page.

In a legal landscape where precision and attention to detail are paramount, Legal Cloud stands out as a beacon of reliability. Advocate Singhania's leadership and the team's dedication make Legal Cloud a go-to destination for all your legal needs.

Hi, I'm Arogyam Nutrition Dietician, and I must express my admiration for the insightful content on your website, which resonates with my passion for holistic well-being. As a seasoned nutrition professional dedicated to transforming lives through personalized dietetics, I find your comprehensive array of nutrition services truly commendable.Since 2009, Arogyam Nutrition has been committed to guiding individuals toward healthier lives. In my journey as a Dietician, I've discovered the significance of a balanced and specialized diet in promoting overall well-being. Your exploration of Monsters and the Poetic Imagination in The Faerie Queene by Maik Goth, and Mermaids and the Production of Knowledge in Early Modern England by Tara Pedersen, draws intriguing parallels to the diverse and tailored nutrition plans we provide.For those seeking tailored dietary solutions, our Healthy Heart Program stands as a beacon, offering specialized diet food for heart patients. Our commitment goes beyond the conventional, echoing the depth and insight found in your scholarly discussions.

Link / Reply

Link / ReplyStep into the enchanting world of festmarket your go-to e-commerce haven! Uncover a diverse array of treasures, from exquisite jewelries to essential medicines and nutrients. Dive into the spellbinding journey inspired by Maik Goth's Monsters and Tara Pedersen's mermaids.Among the marvels, don't miss the Dhootapapeshwar Kaklarakshak Yog Tablet 30 tab – a wellness elixir. FestMarket isn't just a marketplace; it's a portal to a poetic shopping experience. Discover the extraordinary in every click at FestMarket!

Hey there! Loved your insights on monsters and mermaids. Speaking of unique finds, check out BigValueShop for a diverse range of products - sports gear, medicines, nutrients, and more. Don't miss our star product, the ToyTales Snooby Dog – buy it online in India here: buy ToyTales Snooby Dog online in India. It's not just shopping; it's an experience. Happy exploring!

Link / ReplyIn the realm of literary exploration, Maik Goth delves into the profound depths of imagination within Edmund Spenser's "The Faerie Queene," unraveling the intricate tapestry of monsters and the poetic imagination. In parallel, Tara Pedersen navigates the seas of knowledge production in Early Modern England, focusing on the enigmatic realm of mermaids. These scholars illuminate the creative landscapes that captivated the minds of their respective eras, weaving fantastical narratives that transcend time. Similarly, in the tech support realm, we, at https://www.technical-help-support.com/router-keeps-dropping-internet/, draw parallels by embarking on a journey to tame the modern-day monsters that plague digital landscapes. Just as Spenser's knights faced formidable creatures, users today grapple with persistent internet disruptions. Our dedicated team, equipped with the prowess akin to the poetic imagination, tackles the intricacies of router issues, ensuring a seamless online experience. Much like the mermaids' elusive knowledge in Pedersen's narrative, our technicians skillfully navigate the depths of router intricacies, offering not only solutions but also a wealth of understanding. At the intersection of literature and technology, we embody a modern-day chivalry, guarding against the monsters that disrupt your digital quests. With each resolved issue, we contribute to the ongoing saga of conquering challenges, both in the realms of imagination and the virtual world.

Link / Reply

Link / ReplyIn the enchanting realms of literature, the exploration of fantastical creatures like those depicted by Maik Goth in "Monsters and the Poetic Imagination in The Faerie Queene" intertwines seamlessly with the pursuit of knowledge portrayed by Tara Pedersen in "Mermaids and the Production of Knowledge in Early Modern England." Just as these scholars delve into the mysterious and mythical, we, at technical-help-support, embark on a journey of our own, offering technical support services to troubleshoot the modern-day conundrums faced by laptop users struggling with internet connectivity. In the vast tapestry of technology, we are the guiding thread, weaving solutions to ensure a seamless online experience for our clients.

Maik Goth's exploration of monsters and the poetic imagination in The Faerie Queene resonates with the challenges individuals face when their computer can't connect to WiFi. In the realm of tech support services, our mission aligns with Tara Pedersen's insights on mermaids and the production of knowledge in Early Modern England. Just as Pedersen delves into the mysteries of mermaids, our team at [help-n-support] navigates the complexities of resolving issues like "computer can't connect to WiFi." Through our expertise and commitment, we aim to unveil the secrets of seamless connectivity, offering solutions that transcend the mythical barriers encountered in the digital landscape. Visit [help-n-support] for transformative tech support, ensuring your devices sail smoothly through the virtual seas.

Link / ReplyIn the realm of literary exploration, Maik Goth's examination of Monsters and the Poetic Imagination in The Faerie Queene and Tara Pedersen's insightful research on Mermaids and the Production of Knowledge in Early Modern England unveil the profound interplay between folklore and the human psyche. Similarly, in the tech support domain, where intricate challenges demand a nuanced approach, we at Call Voice Support thrive in unraveling complexities akin to the intricate narratives spun by these scholars. Navigating through the digital landscape can sometimes feel as perplexing as encountering mythical creatures. If you find yourself in a maze akin to Spenser's allegorical tapestry or grappling with the enigma of mermaid lore, our experts, specializing in troubleshooting issues like 'cannot receive emails' as addressed on callvoicesupport, stand ready to guide you through the maze of technical intricacies with a commitment to clarity and resolution.

Link / ReplyIn exploring the captivating realms of Maik Goth's Monsters and the Poetic Imagination in The Faerie Queene and Tara Pedersen's insightful study on Mermaids and the Production of Knowledge in Early Modern England, one is reminded of the intricate narratives that shape our understanding of mythical creatures. Much like the intricate tales spun by these literary scholars, our tech support services at callcontactsupport provide a modern-day narrative, addressing the challenges faced by users unable to receive emails. In a world where information flows like the currents around mermaids, we navigate the digital seas, offering assistance as seamlessly as the poetic imagination weaves its tales. Our commitment echoes the diligence found in scholarly pursuits, ensuring a smooth and uninterrupted communication experience for our users.

Link / ReplyExploring the enchanting realms of literature, Maik Goth delves into the poetic imagination in "The Faerie Queene," unraveling the tapestry of monsters and mythical creatures. Just as the narrative weaves a fantastical world, our tech support services at call-contact-support strive to untangle the mysteries of digital landscapes. Much like Tara Pedersen's examination of mermaids shaping knowledge in Early Modern England, we navigate the currents of information to ensure emails flow seamlessly.

Link / ReplyIn the intricate tapestry of early modern literature, scholars like Maik Goth delve into the realms of monsters and poetic imagination within Edmund Spenser's "The Faerie Queene." Goth's exploration reveals the rich interplay between fantasy and reality, mirroring the delicate dance of mermaids in Tara Pedersen's scholarship on the production of knowledge in Early Modern England. As a tech support service provider, we understand the importance of seamlessly navigating through virtual landscapes, much like the symbolic landscapes painted by these literary scholars. If you find yourself lost in the digital wilderness, struggling with Gmail issues such as emails not coming through, our dedicated team at contactsupportgroup is here to guide you back to the shores of a smooth online experience.

Link / Reply

Link / ReplyIn exploring the intersection of literature and folklore, Maik Goth's analysis of Monsters and the Poetic Imagination in The Faerie Queene and Tara Pedersen's examination of Mermaids and the Production of Knowledge in Early Modern England present captivating insights into the fantastical realms of storytelling. Just as these scholars delve into the imaginative landscapes of the past, our tech support services at printersupportnumber.com embark on a journey to simplify the present-day challenge of Installing a Printer. Navigating the complexities of technology, our dedicated team ensures a seamless experience, much like the poetic tapestry spun by Goth and Pedersen in unraveling the mysteries of mythical creatures.

Thank you for sharing this extensive summary of Maik Goth's and Tara Pedersen's works on monsters in Early Modern literature, particularly in relation to Edmund Spenser's "The Faerie Queene." Both authors seem to offer valuable insights into the representation and significance of monsters in Spenser's work, albeit with different emphases and approaches.

Link / ReplyIf you're as intrigued as I am about technical solutions, I highly recommend checking out my latest blog post

"Roku Not Working": This headline suggests that users are facing issues with their Roku device's functionality beyond connectivity problems. It could include issues like freezing, crashing apps, or the device not responding to commands. Troubleshooting steps may involve restarting the device, updating software, or performing a factory reset.

Goth's study appears comprehensive and ambitious, aiming to provide a thorough examination of monsters throughout "The Faerie Queene" and placing them within various contexts such as teratology, history, and literature. By categorizing monsters under different types and analyzing their relevance to Early Modern discourse on poetic creation, Goth offers a nuanced understanding of Spenser's portrayal of the monstrous.

Link / ReplyIf you're as intrigued as I am about technical solutions, I highly recommend checking out my latest blog post.

"Samsung Printer Support": This headline suggests that users are seeking assistance or troubleshooting help related to their Samsung printer. Users may encounter issues such as printer not connecting to the computer, paper jams, print quality problems, or error messages. They may be looking for support resources provided by Samsung, such as online guides, driver downloads, customer service helplines, or community forums, to resolve their printer-related issues effectively.

On the other hand, Pedersen's focus on mermaids offers a more specific lens through which to examine monsters in Early Modern literature, particularly in relation to cultural and literary trends of the time. While her work may not delve as deeply into "The Faerie Queene" as Goth's does, it still sheds light on Spenser's engagement with monstrous themes and how they intersect with broader cultural debates.

Link / ReplyIf you're as intrigued as I am about technical solutions, I highly recommend checking out my latest blog post

"Cisco Router Login Issue": This headline indicates that users are experiencing difficulties accessing the administrative interface or settings page of their Cisco router. Users typically need to log in to their router to configure settings such as Wi-Fi networks, security options, and firmware updates. Common issues preventing login could include forgotten passwords, incorrect login credentials, or technical glitches with the router's interface. Troubleshooting steps might involve resetting the router to default settings, attempting alternative login methods, or seeking assistance from Cisco support resources such as online guides, customer service helplines, or community forums.

these works contribute significantly to our understanding of monsters in Early Modern literature and enrich our appreciation of Spenser's poetic imagination and engagement with cultural and literary debates of his time.

Link / ReplyIf you're as intrigued as I am about technical solutions, I highly recommend checking out my latest blog post.

"Acer Support": This headline suggests that users are seeking assistance or troubleshooting help related to products manufactured by Acer, a prominent computer and electronics company. Users may encounter issues such as hardware malfunctions, software problems, driver updates, or warranty inquiries with their Acer laptops, desktops, monitors, tablets, or other devices. They may be looking for support resources provided by Acer, such as online guides, customer service assistance, or technical support forums, to troubleshoot and resolve their Acer product-related issues effectively.

Both Maik Goth's exploration of monsters in The Faerie Queene and Tara Pedersen's examination of mermaids in early modern England provide fascinating insights into how these mythical creatures shape and reflect the cultural imagination of their time. Their works beautifully merge literary analysis with historical context, offering a deep understanding of how these figures contribute to the production of knowledge and poetic creativity.

Link / Reply<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-dmt-crystals-online/' title='Order DMT Crystals Online' target='_blank'>Order DMT Crystals Online</a>

Link / Reply<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-burmese-cubensis-shrooms/' title='Order Burmese Cubensis Shrooms' target='_blank'>Order Burmese Cubensis Shrooms</a>

<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/about-us/' title='Buying Cocaine Online' target='_blank'>Buying Cocaine Online</a>

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/about-us/ />https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/contact/

Link / Replyhttps://trustednacorticsvendor.com/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/how-to-order-amphetamine-dark-web/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/shipping-and-returns-where-can-i-buy-cocaine/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-crack-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-colombian-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/bolivian-cocaine-online/ />https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-8-ball-cocaine-online/

Link / Replyhttps://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-pink-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-peruvian-cocaine-online-cocaine-8-ball/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lavada-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-fl%d0%b0k%d0%b5-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-fish-scale-cocaine/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-white-china-heroin-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-brown-heroin-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-black-tar-heroin-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-oxycodone-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-fentanyl-citrate-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-adderall-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-abstral-sublingual-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-fentanyl-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-crystal-meth-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-ab-pinaca-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-ab-chminaca-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-a-pvp-crystals-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-4-cmc-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-4-aco-dmt-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-3-meo-pcp-online/ />https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-3-fpm-crystalline-powder-online/

Link / Replyhttps://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-25i-nbome-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-2-nmc-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-fluoromethamphetamine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-scopolamine-powder-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-codeine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-methoxetamine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-mephedrone-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-mdma-powder-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/krokodil-desomorphine/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-ketamine-injection-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-ketamine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-flakka-online-2/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lsd-tab-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lsd-sheet-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-lsd-powder-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lsd-edible-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lsd-blotter-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lsd-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-dmt-powder-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-dmt-crystals-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-burmese-cubensis-shrooms/

https://web.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=122098815758441352&set=a.122098293476441352

https://t.me/Peruviancocainee />https://web.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61563240572171

Link / Replyhttps://web.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61563931824512

https://web.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61563272777571

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/cjZEZsPcFu9B6ikr/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/z9sR4PUrEJyibHoB/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/dtJqxNGCutRcxySt/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/wcPpiXJxJLBQrTRc/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/W8Fu4frdx1qbijuX/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/uK63q6mduMdA35HJ/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/9TKeSnXpoMrVMB9F/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/B8RiZ7FLgGwW49h8/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/62kaFr8CAAoP7oZk/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/RZbFCovTffCmQ9AJ/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/52J18yAyCaJWgmPp/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/V1FWFMJAnZnQjfAF/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/VwB4m65GdsCrGmc5/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/Us1sddi1JxufBUN3/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/1w6KUAywjHSwndf9/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/xQBFuwD5kJzjeGzk/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/YdfwcxMeQ23Vhjdr/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/NTMnZBn3fMFuiRqH/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/LNqYuNZgrgoB3MCs/

https://web.facebook.com/share/uVWvtwPTy6YGG36A/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/RtSkzmNc9r4egNrG/

https://web.facebook.com/share/sN1yneiaZvyyUFYC/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/about-us/ />https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/contact/

Link / Replyhttps://trustednacorticsvendor.com/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/how-to-order-amphetamine-dark-web/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/shipping-and-returns-where-can-i-buy-cocaine/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-crack-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-colombian-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/bolivian-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-8-ball-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-pink-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-peruvian-cocaine-online-cocaine-8-ball/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lavada-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-fl%d0%b0k%d0%b5-cocaine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-fish-scale-cocaine/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-white-china-heroin-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-brown-heroin-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-black-tar-heroin-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-oxycodone-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-fentanyl-citrate-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-adderall-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-abstral-sublingual-online/ />https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-fentanyl-online/

Link / Replyhttps://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-crystal-meth-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-ab-pinaca-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-ab-chminaca-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-a-pvp-crystals-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-4-cmc-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-4-aco-dmt-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-3-meo-pcp-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-3-fpm-crystalline-powder-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-25i-nbome-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-2-nmc-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-fluoromethamphetamine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-scopolamine-powder-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-codeine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-methoxetamine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-mephedrone-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-mdma-powder-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/krokodil-desomorphine/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-ketamine-injection-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-ketamine-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-flakka-online-2/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lsd-tab-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lsd-sheet-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-lsd-powder-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lsd-edible-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lsd-blotter-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-lsd-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/buy-dmt-powder-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-dmt-crystals-online/

https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-burmese-cubensis-shrooms

https://web.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=122098815758441352&set=a.122098293476441352 />https://t.me/Peruviancocainee

Link / Replyhttps://web.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61563240572171

https://web.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61563931824512

https://web.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61563272777571

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/cjZEZsPcFu9B6ikr/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/z9sR4PUrEJyibHoB/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/dtJqxNGCutRcxySt/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/wcPpiXJxJLBQrTRc/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/W8Fu4frdx1qbijuX/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/uK63q6mduMdA35HJ/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/9TKeSnXpoMrVMB9F/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/B8RiZ7FLgGwW49h8/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/62kaFr8CAAoP7oZk/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/RZbFCovTffCmQ9AJ/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/52J18yAyCaJWgmPp/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/V1FWFMJAnZnQjfAF/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/VwB4m65GdsCrGmc5/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/Us1sddi1JxufBUN3/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/1w6KUAywjHSwndf9/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/xQBFuwD5kJzjeGzk/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/YdfwcxMeQ23Vhjdr/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/NTMnZBn3fMFuiRqH/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/LNqYuNZgrgoB3MCs/

https://web.facebook.com/share/uVWvtwPTy6YGG36A/

https://web.facebook.com/share/p/RtSkzmNc9r4egNrG/

https://web.facebook.com/share/sN1yneiaZvyyUFYC/

<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-dmt-crystals-online/' title='Order DMT Crystals Online' target='_blank'>Order DMT Crystals Online</a>

Link / Reply<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-burmese-cubensis-shrooms/' title='Order Burmese Cubensis Shrooms' target='_blank'>Order Burmese Cubensis Shrooms</a>

<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/about-us/' title='Buying Cocaine Online' target='_blank'>Buying Cocaine Online</a>

<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/contact/' title='Cocaine For Sale' target='_blank'>Cocaine For Sale</a>

<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/' title='Where To Buy Cocaine' target='_blank'>Where To Buy Cocaine</a>

<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/how-to-order-amphetamine-dark-web/' title='amphetamine dark web' target='_blank'>amphetamine dark web</a>

<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/shipping-and-returns-where-can-i-buy-cocaine/' title='Where Can I Buy Cocaine' target='_blank'>Where Can I Buy Cocaine</a>

<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-crack-cocaine-online/' title='8 Ball Of Cocaine' target='_blank'>8 Ball Of Cocaine</a>

<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/order-colombian-cocaine-online/' title='fish scale cocaine' target='_blank'>fish scale cocaine</a>

<a href='https://trustednacorticsvendor.com/product/bolivian-cocaine-online/' title='Order Bolivian cocaine online' target='_blank'>Order Bolivian cocaine online</a>

This post was really helpful. I learned a lot of new information from it. I will visit often!

Link / Replyhttps://gamenara.net

Interesting topic. It was explained really well and easy to understand. Looking forward to the next post!

Link / Reply<a href="https://totolas.com/">totolas</a>

Thanks for the great info. It was especially helpful to learn more about [specific information]. Please update often!

Link / Reply[url=https://totolas.com/]totolas[/url]

[totolas](https://totolas.com/)

Link / ReplyThis post was really helpful. Thank you for the information. I will be visiting often!

Fascinating analysis of mythical creatures in literature! Both works explore how monsters shaped cultural narratives. Reminds me of Friday Night Funkin's creative take on modern monster mythology with characters like Lemon Demon. The mermaid angle particularly interests me - it's cool how these medieval/Renaissance perspectives on supernatural beings still influence today's pop culture and games. https://fridaynightfunkingame.io />

Link / ReplyLooking to enhance your brand’s reputation? Buying Trustpilot reviews can help you stand out! Get authentic feedback that drives trust and attracts customers. Contact us today at +918302803616 to learn more and start transforming your online presence!

Link / ReplyIt really highlights how mythology shapes our perspectives. Speaking of creative escapes, if anyone is looking for a fun way to engage the imagination, I recommend checking out the Slope Unblocked game. It’s a thrilling way to spark creativity while enjoying gameplay! https://slopeunblockedd.github.io />

Link / ReplyAvkalan.ai's Generative AI services empower businesses with advanced AI-driven content creation, automation, and decision-making. We leverage cutting-edge models for text, image, and data generation, enabling innovation, efficiency, and personalized user experiences across industries.https://avkalan.ai/services/generative-ai/

Link / ReplySportzfy is an Android application for live sports streaming

Link / ReplyBloxstrap is an open-source, feature-packed alternative bootstrapper for Roblox. It lets you customize your Roblox experience with mods, flags, themes, ...

Link / ReplyYou must log in to comment.