.

.

Albert Charles Hamilton (born Goddard); July 20, 1921- June 14, 2016.

Cappon Professor of English, Queen’s University, Canada

Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada

Author:

The Structure of Allegory in ‘The Faerie Queene.’ Clarendon P, 1964.

The Early Shakespeare. Huntington Library, 1967.

Sir Philip Sidney: A Study of his Life and Works. Cambridge UP, 1977.

Northrop Frye: Anatomy of his Criticism. U of Toronto P, 1990.

and many articles on Renaissance literature.

Editor of

Essential Articles for the Study of Edmund Spenser. Archon Books, 1972.

The Faerie Queene. Longmans Annotated English Poets. Longman, 1977, 1980.

The Faerie Queene. 2nd ed. Text edited by Hiroshi Yamashita and Toshiyuki Suzuki. Longman, 2001.

The Spenser Encyclopedia. Ed. A. C. Hamilton, et al. U of Toronto P, 1990, rpt. 1996.

A. C. Hamilton—known to his Spenser colleagues as “Bert”—was born in Winnipeg and attended the University of Manitoba. His surname was originally Goddard but his father died when he was young and he took his stepfather’s surname. He had local Cree relations by marriage, including an uncle on whose farm he worked, haying and caring for livestock. He was from Winnipeg’s tough north end, which was separated from the rest of the city by the huge CPR train yards, and which consistently elected Communist Party of Canada aldermen. The family was poor—this was the Great Depression—and Bert had to win scholarships if he was to attend university. He did so and excelled in the sciences, taking his degree in chemistry and, incidentally, working in the armaments laboratory on fuses. He would later attend the University of Toronto (M.A.), studying with Northrop Frye, followed by Cambridge University, where he took his doctorate in 1953 under the supervision of E. M. W. Tillyard, master of Jesus College. There, in the Cambridge City Hall, he married his dearly loved wife Mary, who was also from Winnipeg, and as hardy as Bert. He began his teaching career at the University of Washington, in Seattle, moving to Queen’s University, Canada, in 1968, in part because he did not want his sons to be drafted into the US military during the Vietnam War, to which he was opposed on principle.

He had a record of such opposition. In 1944, when he was in his final undergraduate year, the student paper, The Manitoban, published a strongly worded anti-war poem, “Atrocities,” on the occasion of the Prime Minister’s denunciation of the Japanese for torturing Canadian prisoners of war. But the “Atrocities” of the title refer to the actions of the “damnable hypocrites” on the home front, including “all members of the government” and the “Bible-thumpers” prating their “long disbelieved / Christianity.” It would be “a matter / Of rejoicing” if these big politicians and war boosters were to suffer instead: “The fault of war / Is that it kills the wrong people.”[1] It should be said that in its later stages—which I doubt most readers reached—the poem engages in subtler, indeed almost incomprehensible, thinking about war. These were the last unclear sentences Bert ever wrote. But they show a young mind impatient with wartime clichés and struggling alone with great questions.

Unsurprisingly, a scandal ensued and the word “treason” was used. One professor declared in lecture that the author, whoever he is, should be hanged from the tree outside the hall. Anyone who knew Bert will not be surprised he came forward to own up to his words, without any retraction, and to take the consequences. There was general astonishment. He was at the time head of the student union, captain of the debating team, and an all-round academic star. Passions cooled and he was allowed to complete his course of study. But his degree was withheld until he completed his own military service, which he did in the navy, with honor, in the battle of the Atlantic.

At the University of Toronto Bert switched from chemistry to the study of English Literature, “the soft option,” as he later described it. Northrop Frye taught his first graduate seminar, which was on William Blake. There was only one other student, Hugh Kenner, himself destined for greatness as the author of The Pound Era and already something of a legend for brilliance. After that first seminar meeting, English didn’t seem so soft after all. So at least Bert described the episode to me—with, I suspect, pardonable modesty about his own contributions.

This is not the place to describe at length Bert’s books and many articles, which are well known to Spenserians, especially The Structure of Allegory in the Faerie Queene, based on his Cambridge dissertation, and widely regarded as the groundbreaking work for modern scholarship on the poem. His edited collection, Essential Articles for the Study of Spenser, harvests the best that had been thought and said on the poet, mostly in the 1960s, an especially fruitful decade for Spenser criticism. Four and a half decades later, this collection remains the best point of departure for the serious study of Spenser. Bert’s wise and trenchant study of Sir Philip Sidney’s life and works is still regarded as the best all-round study of Sidney’s career as poet, courtier, and literary theorist. It is filled with impregnable literary-critical assertions, such as that Sidney’s Apology of Poetry is the best-written work of literary criticism in English. Less well known is The Early Shakespeare, a neglected gem of a book with, among much else, the most lucid reflections on a subject that is old and obscure but of obvious importance: the influence of Spenser on Shakespeare.

Also less known to Spenserians, at least to those in the United States, is Northrop Frye: Anatomy of his Criticism, published in the year of Frye’s death. This magisterial study, focused on Anatomy of Criticism (1957), takes in Frye’s twenty-four books and more than three hundred articles and reviews, assessing his impact “before structuralism and its aftermath” (xv).[2] Of special interest to Bert was that Anatomy of Criticism began as a methodological introduction to a book on Spenser. By the 1980s, when Bert began to write, Frye was safely out of fashion and so open to consideration from a wider perspective, which was nothing less than the humanist engagement with poetry from its rise in the Renaissance to its apparent decline and fall in our own time. So at least it seemed in 1990, as Bert said, quoting the vatic pronouncement of the late Geoffrey H. Hartman, “we are now nearing the end of this Renaissance humanism.”

Bert argues that Frye’s work, in its strongly left-leaning, socialist inflection (an aspect of Frye largely invisible to American readers) embodies the moral drive of the humanist tradition, insisting that literature show us where we should be going as a society and what we should be moving away from. Literature is our moral and social compass, even as it takes us into different moral worlds, as The Faerie Queene does. Yet with its strong scientific claims, its scorn of impressionistic belles lettres, and its insistence on professionalizing criticism (as bibliography had been professionalized), Anatomy of Criticism hastened the rejection of the values it embodied. Bert went on to write critically but with discerning sympathy on deconstructionism and the new historicism, notably in “The Renaissance of the Study of the English Literary Renaissance.”[3]

Five years after Essential Articles, Bert brought out his great edition of The Faerie Queene in the Longman Annotated English Poets series, with the Oxford text of J. C. Smith. The notes and other apparatus, including beautiful essays on each book of the poem, established Hamilton’s reputation as one of the most important editors of Spenser since the eighteenth century, and as the greatest line-by-line explicator of Spenser ever. Although it is the first entirely professional edition of The Faerie Queene (however much we value the Hopkins Variorum), it never loses sight of the student and the first-time reader. Bert once remarked that the task of editing The Faerie Queene might be guessed at by considering the first line of Book One, with its three substantives and one adjective, each of which has changed its meaning since Spenser’s day: gentle, knight, pricking, plaine. There is not a line in The Faerie Queene—a poem three times as long as Milton’s Paradise Lost—that Bert did not, like the speaker of Frost’s “After Apple Picking,” cherish in hand. But unlike Frost’s speaker, Bert finished the job (twice, for a second updated edition appeared in 2001) and he was never tired.

Despite his own decided views, Bert was generous in incorporating other scholars’ work in the notes to his edition, making it, as one of my appreciative students put it, “an interlineary bibliography.” The fully revised second edition, with its new text edited by Hiroshi Yamashita and Toshiyuki Suzuki, is a testament to the internationalizing of Spenser studies in which Bert played such an important role. I know of no other edition of an English poet that is so welcoming to beginning scholars and so continuingly useful to the experienced.

But yet the end is not. The largest project of Bert’s career was the monumental Spenser Encyclopedia, published in 1990, a giant three-columned tome of which he was not only the editor in chief—a responsibility thrust upon him by the Spenser Society—but also the labor-intensive close reader, corrector, and ghost writer of hundreds of entries. (I disclose here I wrote three entries and received helpful comments on all of them.) The Spenser Encyclopedia is one of the miracles of scholarship at the end of the age of printed reference works. (Patricia Parker’s Shakespeare Encyclopedia, originally destined for print, will appear from Stanford instead as an open-access on-line edition modeled on the great Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.) The Spenser Encyclopedia is virtually an encyclopedia of the literature of the Renaissance and of every ancient author and cultural trend with which Spenser was concerned. But it was also, in its day, boldly up to date in new trends in critical theory and historical scholarship. It remains the indispensable, authoritative work for Spenserians in our time, and for the foreseeable future.

For several years Bert went with his entire family—his four sons and his wife Mary—on summer-long canoe trips in the harsh, tree-less and scarcely traveled landscape of the barren lands of the Canadian far north, following the routes of the original explorers and passing through regions with many different native language groups. Described in several hair-raising books by Farley Mowat, for example, Lost in the Barrens (1956) and Never Cry Wolf (1963), by Eric Morse in Freshwater Saga (1987) (Morse was a personal friend of Bert and Mary’s), and by Sigurd Olson in his classic work, The Lonely Land (1961), this is a region of immense vistas, rugged terrain, polar bears, gigantic rapids, and unspeakable solitude, despite occasional, and, it should be said, always amiable encounters with native groups.[4] In the 1960s, Bert’s was among the very early parties of recreational canoeists to make the epic journey from Great Slave Lake eastwards over the continental divide, crossing what was then the Northwest Territories (now the Inuit-administered Nunavut) and ending at the native settlement of Baker Lake, on Hudson Bay. Bert’s family was also one of the first non-professional groups to paddle the north-flowing Coppermine River to the Arctic Ocean, on the route of the eighteenth-century explorer, Samuel Hearne. (After several failures, Hearne paid woodland Cree to take him down the Coppermine, which they did for some distance before abandoning him. Hearne’s claim to have finished the journey alone is dubious, given his inaccurate description of the lower reaches of the river. But Bert Hamilton’s claim is not.) In Frontenac Park north of Kingston, up into his late seventies, Bert led his sons on hikes that avoided any paths, bushwhacking over ridges in dense forest and crossing any water obstacles encountered by putting clothes and hiking boots in plastic bags and swimming across, to continue on the far side. In a 1982 interview in the Kingston Whig-Standard Bert said his family canoe trips gave “that sense of exactly what Canadians need: of being alone in the wilderness, and we’re alone as a family. And of course as a father I just love it.”[5]

For twenty years after his retirement, Bert spent his days caring for his ailing wife Mary, who was also an author and co-wrote a classic work, “And Some Brought Flowers,” on flora encountered on the canoe routes by Canada’s explorers and voyageurs.[6] In the early morning hours and late at night, when Mary was sleeping, Bert continued to write. He kept up an enormous email correspondence with Spenserians and Renaissance scholars around the world. Unusually for a retiree, he complied with the many requests that scholars of his eminence receive to donate their time to consulting on promotions and appointments. He wrote endless letters of recommendation and advised younger authors on entire book manuscripts. He would respond carefully and in detail to anyone, students included, who wrote to him.

A. C. Hamilton labored mightily to promote Spenser studies in the world and, not incidentally, to raise still higher the profile of Canadian scholarship, especially in Renaissance studies. In a collection of essays dedicated to him, Unfolded Tales: Essays in Renaissance Romance, Northrop Frye wrote the following tribute:

a first rate scholar, simply by being what he is and by what he does, creates and fosters a community around him, a community not of discipleship but of high morale sustained by the awareness that he is there. (xii) [7]

As long as his great edition of The Faerie Queene and the still greater Spenser Encyclopedia last, A. C. Hamilton will indeed be there for Spenserians. I quote again from the 1982 interview for the Kingston Whig-Standard:

[Spenser] was the kind of poet I just liked. If you’re interested in research, you’re waiting around for something to possess you, waiting for some kind of topic that you can latch yourself on to. This is something I learned from Frye: the importance of having a spiritual guru as he calls it, the kind of person you can grow up with and in. Someone you can live with for a long time. I find it hard to formulate why I got onto Spenser because he’s not the kind of person who makes you aware of his personality the way William Blake does… . I guess I looked upon The Faerie Queene as the kind of poem that I would like to spend time in, and was successful. Spenser is not a poet I’ve in any way outgrown.

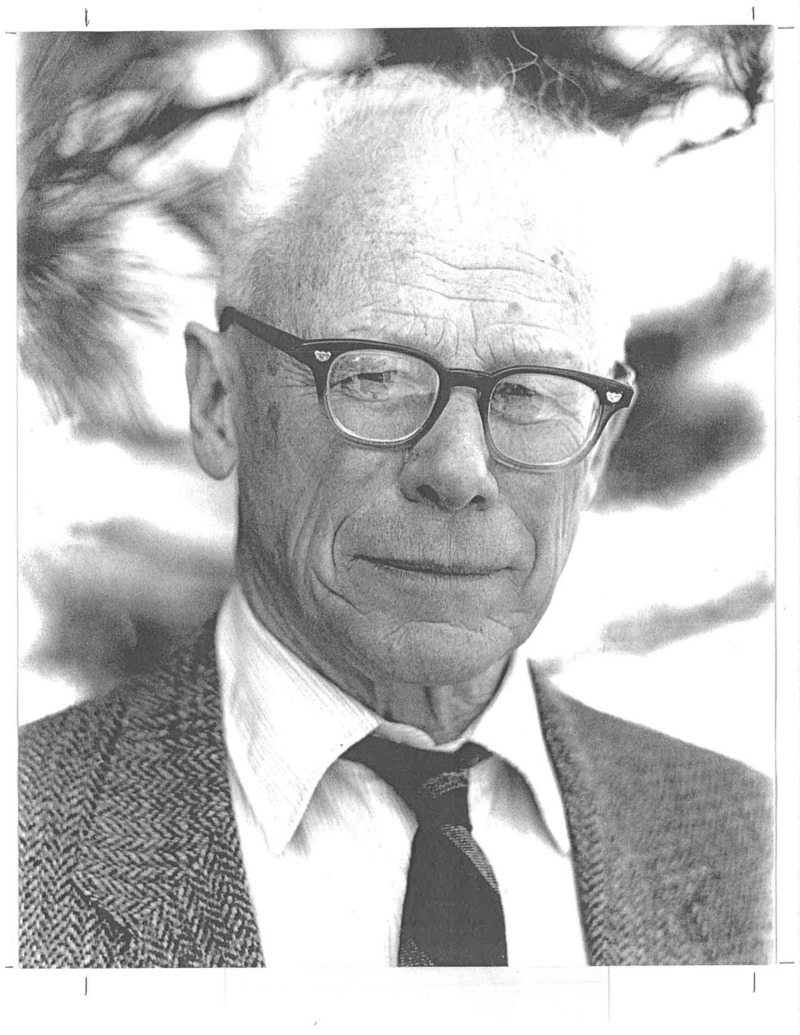

I know of two excellent photographs of A. C. Hamilton. The first, dating from his student days, is of an elegant and principled young man, either at Cambridge or the University of Toronto. It is published with Laurence Wall’s obituary in the Toronto Globe and Mail (August 1, 2016). [8] The second, by Alec Ross, which is shown here, was taken when Bert was a senior scholar, at about age 69, and is published in Unfolded Tales: Essays on Renaissance Romance. It shows the essential kindness behind the formidable austerity. It also shows the toughness of a man who knows long trails, the arctic wind of the barrens, and the business end of a paddle.

Thanks to Ross Hamilton, ACH’s son and also a professor of English; to George M. Logan, ACH’s department chair and colleague at Queen’s University; and to Laurence Wall, CBC journalist and author of the Globe and Mail obituary of ACH.

[1]The Manitoban Literary Supplement, 18 Feb. 1944, p. 3, http://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm:1425318/.

[2] See Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism, Princeton UP, 1957.

[3] English Literary Renaissance, vol. 25, no. 3, September 1995, pp. 372-87.

[4] See Farley Mowat, Lost in the Barrens, Little, Brown, 1956, Never Cry Wolf, Little, Brown, and Company, 1963, Eric Morse, Freshwater Saga, U of Toronto P, 1987, and Sigurd Olson, The Lonely Land, Knopf, 1961.

[5]Peter Miller, “A. C. Hamilton: Spenser Scholar,” The Whig-Standard Magazine, Kingston, Ontario (Canada), October 2nd, 1982, pp. 4-6.

[6]Mary Alice Downie, Mary Hamilton, and E.J. Revell, “And Some Brought Flowers”: Plants in a New World, U of Toronto P, 1983.

[7] Unfolded Tales: Essays on Renaissance Romance, edited by George Logan and Gordon Teskey, Cornell UP, 1989.

[8]Laurence Wall, “Bert Hamilton’s Distinguished Academic Life Began with Controvery,” The Globe and Mail, Philip Crawley, 31 July 2016, http://fw.to/WbSg3ah/.

46.2.2

Comments

Thank you this reflection. Professor Hamilton's edition of Spenser and the Encyclopedia he edited have been wonderful guides to my studies and I'd often wondered about the man behind these texts. Knowing a little now about his career, family and his outdoors travels will make reading his books more meaningful.

Link / ReplyInvestor sentiment, often driven by news, social media, and trends, can significantly impact prices. Positive news can lead to increased buying, while negative news can trigger selling. https://bettingsites.ltd/

Link / ReplyYou must log in to comment.