Possession: Ideas for Further Reading

Monday, September 14th, 2009Possession is an unusual novel, weaving past and present together, and thinking hard about its own and other literary writing. Two of the Cambridge Authors team - Raphael Lyne and graduate editor Sylvia Karastathi - felt it might be worth making suggestions about a range of novels that someone might read next, depending on what really caught your imagination in Possession. If you have your own ideas, you can add them at the end.

Below you'll find descriptions of novels from two contributors. We've avoided one obvious area: Byatt's own work. However, some of the things you might have found interesting in Possession are revisited in her other novels. For example, The Biographer's Tale (2001) features the writing of a biography about a biographer. The Children's Book (2009) is also about a writer who writes special stories for her own children. Byatt is clearly a writer for whom the fictional worlds within fictional worlds matter a great deal, but she is not alone in this.

Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire (1962)

(Raphael Lyne)

Vladimir Nabokov's novel is, like Possession, centred on the life and work of a poet. There are two central characters. One, the poet John Shade, has died, and part of the book is taken up with the text of his final poem, Pale Fire. The other, Charles Kinbote, a friend and colleague of the poet at a fictional university, provides a foreword and a long commentary on the poem. As the novel unfolds, the reader begins to realise that this commentary is rather strange. It keeps discovering idiosyncratic things in the poem, especially references to the exile of the King of Zembla. Gradually it becomes apparent that the commentator Kinbote thinks he is, or may actually be, the King himself; and that he believes that an assassin sent to kill him has ended up killing Shade. He maintains that the poem records all of this as a result of conversations between the two friends. The book plays a brilliant game with what is true and what isn't, and what the interpreter brings to a poem (or a novel). As well as being wonderfully ingenious and witty, Pale Fire is also full of powerful and poignant moments relating to Shade's life, his friendship with the eccentric Kinbote, and even the strange story of the Zemblan King.

When I read this novel I was already a Nabokov fan, having read Lolita (which I sought out for its controversy, but I enjoyed for its astonishing wit) and Pnin (which was lighter, but still razor-sharp). Pale Fire made me feel newly enthusiastic about the prospect of studying literature: I was amazed that something so clever, ingenious, and intensively designed, could still be moving and emotionally acute. In retrospect I think it might have been quite an important realisation - that being artificial and being affecting need not be at all contradictory. The way it weaves together poetry and fiction is very different from Possession, but in both cases it's fascinating to think about how the poetry is made to fit into the narrative, and also how sometimes it isn't.

John Irving, The World According to Garp (1978)

(Raphael Lyne)

When I was a student I remember being recommended Irving's novel A Prayer for Owen Meany (1989 - it had just come out in paperback), which I loved. As a result I followed up Irving's other novels. I liked The Cider House Rules, which shared with Owen Meany a quirky, richly interconnected set of characters and stories. I also ended up admiring The World According to Garp, the early novel which propelled Irving to public acclaim, but I can remember a particular reaction to it. I thought in some ways it seemed like a particularly adult novel. It is a typical Irving story, in that it is strange, but grand, taking in a whole life, shattering events, and many people's stories. It features some of his characteristic obsessions (e.g. wrestling). It also told of problems in marriages, disappointments in life, infidelity, recovering from trauma, and the fear of loss and death - things of which I was lucky enough not to have much experience at the time. So it seemed a heavier read, though not necessarily a better one, than the other Irvings I had enjoyed. The reason why it might be a thought-provoking comparison for Possession is that it is about a writer's life, work, and career. There are inset passages of his fiction, which itself weaves in and out of the themes of his life, and other characters are readers. So it too is involved in a multi-faceted way with the relationship of lives and novels, and it too has to find a character's literary voice. There is a film of The World According to Garp starring Robin Williams: I think it's pretty good.

Anne Michaels, Fugitive Pieces (1996)

(Raphael Lyne)

Telling the story of the Nazi Holocaust is extraordinarily difficult. Many novelists, film-makers, and other artists, have tried out ways of using their form's limitations and possibilities to capture something of its magnitude and significance. In Martin Amis's novel Time's Arrow things happen backwards, so events of the concentration camp at Auschwitz are turned the wrong way round. I think Time's Arrow is an outstanding novel, but it caused controversy at the time for what seemed to some like a gimmick. Fugitive Pieces finds its perspective on the Holocaust in two connected stories and voices. One is that of the poet Jakob: as a child in Poland, he narrowly escapes being killed by Nazi soldiers. He runs into an archaeologist who takes him away to safety on the Greek island of Zakynthos. The first part of the novel tells the story of his growing up, his life as a poet, his relationships, and the burden of the past. The second part is written from the perspective of Ben, a Canadian academic who admires Jakob's poetry. He is the son of Holocaust survivors, and also feels the burden of his family's suffering. The novel is written by a poet and is highly poetic in style - beautifully but not over-densely written. The place of the poet's work within the novel links with its persistent interests in memory, language, and how one can express and reconcile oneself to the past. Like all the novels I have recommended, it is very different from Possession in many ways. However, like them, it makes a writer into a character, and puts a literary response to events at the heart of the novel.

Margaret Forster, Lady's Maid (1990)

(Sylvia Karastathi)

I was introduced to Margaret Forster's work through a novel that recounts the after-life of a painting by British artist Gwen John. I was struck by her innovative blending of biography and fiction and subsequently found out about her curious first person autobiography of William Makepeace Thackeray, and her more traditional, yet acclaimed, biographies of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Daphne du Maurier.

It is often presumed that the correspondence between Randolph Ash and Christabel La Motte in Possession echoes that of Victorian poets Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning during their courtship and marriage. Their 573 extant letters, the most self-contained correspondence in English literary history, feature musings on art, the readings of the poets, together with practical plans for their escape to Italy. In Lady's Maid she fictionalises the well-documented affair between Barrett and Browning through the perspective of Barrett's real-life maid Elizabeth Wilson. It's a novel that stands on the threshold between biography and fiction, combining elements of the detailed research of the biographer with the imaginative work of the novelist.

It is a trend of 1990s fiction to re-write history through the perspective of marginalised voices - especially those of working class women - whose experience has been overlooked in the official archives. Wilson gets mentioned in the correspondence as indispensable for Barrett's convenience: 'very amiable, easily satisfied, & would not add to the expenses or diminish from the economies' (Barrett's letter of July 1846). Byatt's own concerns in Possession with what kind of 'truth' can escape the archive have been previously articulated in pioneering works of feminist research such as The Diaries of Hannah Cullwick: Victorian Maidservant by Liz Stanley (1984). Forster's novel nods to such textual sources as well as to the jocular tone of Virginia Woolf's Flush, the famous biographical experiment that recounts the life of Barrett's spaniel.

Reading Lady's Maid opens for the reader an alternative world of Victorian life, featuring 16-hour working days, when a lady could barely get out of bed without her maid's help. It also exposes the hidden domestic work that enabled lives of the mind such as Barrett's. As an antidote to Byatt's novels of the mind, that are in constant anxiety about the pressures of domesticity for women, Forster's Wilson reminds us of the hard material circumstances that deprived working people of intellectual pursuits. Using the genre of the epistolary novel Forster gives voice to a historically anonymous character, who, in any other genre, could not have been central to her own life-story.

Lynne Truss, Tennyson's Gift (1996)

(Sylvia Karastathi)

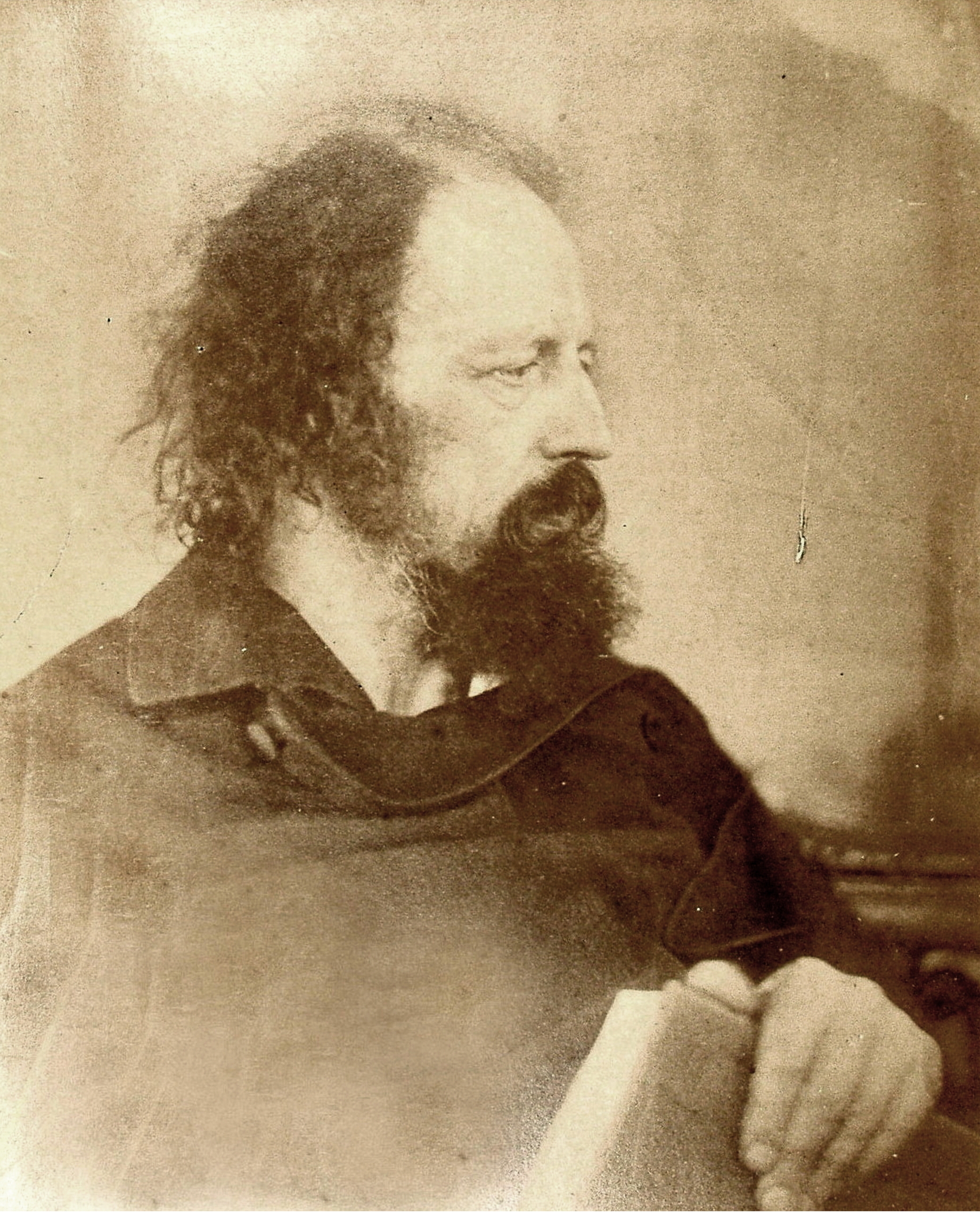

A literary farce about Victorian high-brows? Lynne Truss, author of the famous punctuation book Eats, Shoots and Leaves, which made commas fashionable, writes with humour on the domestic lives and familial relationships of Victorian Literati. On a summer's day on the Isle of Wight Alfred Tennyson, Poet Laureate, is waiting to hear what people think about his latest poem Enoch Arden. His wife is hiding unfavourable reviews as well as letters from unwanted admirers, such as Charles Dodgson (a.k.a. Lewis Carroll). In the house next door the famous photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, Virginia Woolf's great aunt, is making the servants paint the garden roses white for yet another exhausting pre-Raphaelite shoot. Observing the un-literary, mundane, but ultimately human side of famous Victorian artists, Truss's tongue-in-cheek narrative dares to take on the perspective of their closest relations and cast literary legends in a 'domestic' light. One of my favourite moments in the novel occurs at the Tennysons' breakfast table between the laureate and his wife Emily: surprised to find a parody of In Memoriam in the magazine Punch, she eats the page in panic. When her husband asks why, she 'thought quickly. "Perhaps my anaemia craves the mineral in the ink!"'.

Penelope Fitzgerald, The Blue Flower (1995)

(Sylvia Karastathi)

In the debates surrounding the search for the best of the Booker prize winners in the summer of 2008 The Blue Flower was declared the best book that ought to have won the prize but didn't (The Guardian, September 2008). It's the kind of novel about which people sometimes say: 'I've always wanted to read it'. After her death in 2000, Fitzgerald's reputation has soared, with scholars still discovering unpublished stories and letters, but The Blue Flower is seen as her masterpiece. It narrates the early life of Fritz von Hardenberg (1772-1801), student of law, philosophy and history, who later, under the pseudonym Novalis, became a key figure of German Romanticism.

Set in provincial Saxony at the end of the 18th century it provides an excellent introduction to the sensibility of the Romantic Era in 55 short, fleeting chapters. The book's epigraph from Novalis - 'Novels arise out of the shortcomings of history' - befits Byatt's attitude towards the historical novel, and the gaps that it is apt to fill. Fritz's inexplicable love for pre-adolescent Sophie, mundane and ordinary, is at the centre of the novel. I was struck by the elliptical sketches with which Fitzgerald draws her world, in a reticent and restrained manner that is at the same time attentive to the significant details of domestic life. Byatt has many times expressed her admiration for Fitzgerald's novel. Like her own works it is a novel of the mind; recondite and challenging, but alive and entertaining in ways that writing about writers seldom is.

John Fowles, The French Lieutenant's Woman (1969)

(Sylvia Karastathi)

I cannot remember a single other novel that shaped my undergraduate experience of reading English more than Fowles' retrospectively narrated historical novel. Innocent, at the time, to the playfulness and conceits of post-modern fiction, I was taken in (and away) by the over-omniscient narrator, who would offer me alternative endings to the novel, and in a conversational manner would comment on the characters' decisions. I felt almost mocked about my naïve willingness to suspend disbelief and immerse myself in a pseudo-Victorian world, which constantly foregrounded its own artifice. This is not the world of nineteenth century Victorian England, I was constantly reminded, but I was irrevocably gripped.

Taking an 1860s plot and telling it from an 1960s point of view, Fowles's narrator follows the love story of Sarah Woodruff, who lives in Lyme Regis as a disgraced woman, with Victorian nobleman, Charles Smithson. Fowles' novel has often been compared to Byatt's on the basis of the common narrative thread of clandestine love and adultery in Victorian England, as well as the retrospective attitude to a particular historical moment. Fowles, however, is a lot more openly and self-consciously critical of the sexual mores of Victorian society and the hypocrisy surrounding issues like prostitution. Although not a novel about writers, Fowles's novel is affectionately parodying the genres and styles of much Victorian writing. Thomas Hardy and Wilkie Collins resonate in the plot, and the carefully selected epigraphs (from Marx, Darwin, Alfred Tennyson and Mathew Arnold among others) gesture to fictional and non-fictional works that shaped Victorian thought.