Last week I went to a workshop at the annual Royal College of Psychiatrists conference, organised by Neil Hunt, a consultant in Cambridge. They used Shakespeare’s Ophelia, in Hamlet, as a case study. Part of the focus of the event was on evaluating her mental state, and ascertaining signs of suicide risk, on the basis of the evidence in the text. Part of it, which I found particularly intriguing, was addressed to a coroner, defending the actions taken by the psychiatrist who treated Ophelia.

*

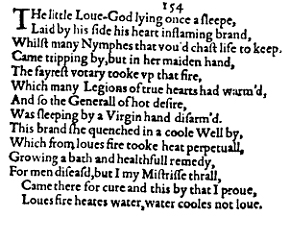

There is, of course, no psychiatrist in the play. However, one was ingeniously excavated from the text. Here is one familiar version of one key scene, taken from the 1623 First Folio edition:

QUEEN

I will not speake with her.

HORATIO

She is importunate, indeed distract,

Her moode will needs be pittied.

QUEEN

What would she haue?

HORATIO

She speakes much of her Father; saies she heares

There’s trickes i’th’world, and , and beats her heart,

Spurnes enuiously at , speakes things in doubt,

That carry but halfe sense: Her speech is nothing,

Yet the vnshaped vse of it doth moue

The hearers to ; they ayme at it,

And botch the words vp fit to their owne thoughts,

Which as her winkes, and nods, and gestures yeeld them,

Indeed would make one thinke there would be thought,

Though nothing sure, yet much vnhappily.

QUEEN

’Twere good she were spoken with,

For she may strew dangerous coniectures

In ill breeding minds. Let her come in.

The queen is troubled by Ophelia, and would rather avoid her. However, she senses that her madness may result from, and could reveal, dark secrets. Horatio, Hamlet’s friend, gives a perplexed but thoughtful description of her incoherent and persistent ramblings. It is likely that this version is revised from the different scene we see in the second quarto (1604):

QUEEN

I will not speake with her.

GENTLEMAN

Shee is importunat,

Indeede distract, her moode will needes be pittied.

QUEEN

What would she haue?

GENTLEMAN

She speakes much of her father, sayes she heares

There’s tricks i’th world, and hems, and beates her hart,

Spurnes enuiously at strawes, speakes things in doubt

That carry but halfe sence, her speech is nothing,

Yet the vnshaped vse of it doth moue

The hearers to collection, they yawne at it,

And botch the words vp fit to theyr owne thoughts,

Which as her wincks, and nods, and gestures yeeld them,

Indeede would make one thinke there might be thought

Though nothing sure, yet much vnhappily.

HORATIO

Twere good she were spoken with, for shee may strew

Dangerous coniectures in ill breeding mindes,

Let her come in.

Here a generic Gentleman reports on his observations of Ophelia, and it is Horatio, not Gertrude, who worries that she might cause suspicious minds to fester. In my Oxford text the editor G.R. Hibbard sees the Folio version as a piece of streamlining. A superfluous role is removed from the play. This seems fair enough, but the differences are consequential. Having Horatio rather than Gertrude fearing loose talk is quite a significant change; and missing out on the Gentleman’s contribution removes the idea that someone – perhaps with expertise – has been given the task of observing Ophelia.

At the conference workshop, a deft change was made: ‘Gentleman’ became ‘Doctor’. This gave the psychiatrists’ workshop a focus for their hypothetical consideration of a professional’s actions and their consequences in a legal framework. This is not entirely unwarranted. In Macbeth there is a palace doctor who witnesses Lady Macbeth’s night-time delusions, and reports upon them to her husband. The Hamlet scene represents a comparable situation, where it seems reasonable to think that the person entrusted with reporting on a sick individual might be qualified to do it.

But this is Elsinore, and this is Tragedy. The psychiatrists found ways of representing both points of view when presenting to the coroner. Ophelia was assessed, but nothing immediate was done: her behaviour wasn’t demonstrably consistent with suicide, and she was in a well-supported environment. On the other hand, the assessment was brief and perhaps inadequate, the patient evidently had disordered and morbid thoughts, and the care plan was too hands-off. Left in an unstable mental state in an impersonal and dysfunctional court, where nobody had shown her sufficient attention or sympathy thus far, it seemed all too predictable that Ophelia had killed herself, or at least put herself in danger.

*

A coroner (or ‘crowner’) is mentioned in Hamlet a little later. The gravediggers sardonically note that the official view is that Ophelia should have Christian burial – she has not committed suicide. They reason, all too plausibly, that her rank and connections must have helped. In the play, as for the psychiatrists, psychological judgments become entwined with legal judgments and social contexts. This might be one reason why considering Shakespeare’s plays seems productive to them. (There must be other reasons of course: the finite evidence, the need or chance to read between the lines, the sense of these narratives being realised and embodied in performance, the quality of psychological insight, the familiarity of the material, its status, its novelty, and so on…)

But the thing I came away thinking about most was care. There is a chilling lack of care for Ophelia. This is not just a judgment on characters, but also on the play itself. So little time is spent on her decline and her crisis. Everything seems to be consumed by Hamlet himself. This is how things are in Tragedy, perhaps, where nurses help you make fatal assignations and doctors cannot do anything to help. It is also the particular situation in which Ophelia finds herself, without anyone to support her.

The doctor-who-isn’t-a-doctor is either very astute or very lax. His main conclusion is that people draw conclusions from Ophelia that suit their own way of thinking. They ‘botch up the words fit to their own thoughts’. This is indeed what happens in Hamlet – to the hero himself when Polonius assumes he is mad for love, but Claudius thinks he is plotting to usurp him. Perhaps it’s a reflection on how difficult it is to interpret other minds on their own terms, even if you are supposed to be an expert. Then again, if we indulge the idea that this Gentleman should have something therapeutic to offer, this may just be a very unproductive medical opinion.

That is, she mutters. This is onomatopoeic, as we might say ‘she hummed and haahed’.

Insignificant things. She gets very worked up about things that don’t matter.

Conclusions.

E-mail me at rtrl100[at]cam.ac.uk