Just as I am posting about how literature might make you think differently, an essay by me comes out that deals (in its own way) with this very thing. My essay ‘Thinking in Stanzas: Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece‘ has appeared in a book called The Work of Form: Poetics and Materiality in Early Modern Culture, edited by Elizabeth Scott-Baumann and Ben Burton. You can read about the volume on the Oxford University Press website here. The line-up of authors is really excellent, and I am pleased to be in it with my rather experimental essay.

I try to bring together (i) the stanza forms of Shakespeare’s poems, and the way they make us think about something over here, set against or in dialogue with something over there; (ii) certain rhetorical tropes (simile, parallel, analogy) that exploit this juxtapositional pattern; (iii) evidence that we organise certain kinds of cognition spatially, as in the ‘mental number line’ that means those in left-to-right writing cultures tend to place low numbers on the left, high numbers on the right. My point is that poems open up thoughts about habits of thinking, what we gain and lose from our tendency to set one thing against another, true and false parallels.

The reason it seems relevant now, given recent posts, is that I think poetry really does change the way we think, within its bounds and beyond. Different poetic forms cause our thinking to take certain shapes, offer tangible reorderings of experience. Perhaps this could be subjected to empirical testing. Would prolonged exposure to Spenser’s 9-line stanza (already mentioned in this post) make people more deliberative, or less ready to come to a point? The main point I want to make here, in addition to noting that my essay has been published, is that if we want to understand how literature changes the way we think, we could and should think about form.

The Problem of Evidence

Michael Mack, How Literature Changes the Way We Think (Continuum, 2012)

Not for the first time, I have been reading a book that is so near to, and yet so far from, my interests in this blog. (Another was Aboutness.) In How Literature Changes the Way We Think Michael Mack argues that literature offers special ways for us to solve problems. He has pursued this passionate defence of literature in .

*

In How Literature Changes the Way We Think Mack argues that the arts have ‘innovative force’, they ‘disrupt homogeneity, , or the reproduction of what we are used to’. He writes about how literature’s ‘mental space has the capacity to change our ways of perception and cognition in a uniquely powerful manner precisely by dint of its separation from what we are used to see as presentations or representations of our world’. It ‘transforms our cognition by undermining the way that fictions keep us enthralled’. Indeed, ‘the cognitive upheavals, which literature initiates and impels, could match the changes in age and longevity that are due to advances in biomedicine’. For Mack, literature’s knowledge is aimed at the future, and for humanity facing its future it is, or should be, ‘key to problem solving due to its life renewing and life preserving impetus’.

This is very much an argument for the present day, and for a particular version of the present, where the world and its societies are aging, and the future poses severe challenges to human resilience, attitudes, and ethics. The argument mostly arises in discussions of writings about art, culture, history, and change by Spinoza, Nietzsche, Arendt, Žižek, Heidegger, and others. When fictional works appear – The Road, 1984, Never Let Me Go – they tend to illustrate the problems rather the solutions, I think. So there aren’t a set of tangible instances of literature presenting readers with new ethical strategies, either in the past or present. And so there are not specific proposals as to how we might take particular texts now and find problem-solving inspiration in them.

*

It may be rather prosaic of me to approach a work of cultural criticism in this way. But it’s consistent with my reason for blogging about it. Mack uses the word ‘cognitive’ often, but although he cites Antonio Damasio on a number of occasions (mostly in relation to the mind / body relationship, and Damasio’s approval of Spinoza) his definition of ‘the way we think’ takes hardly any explicit or extended account of cognitive science, its conclusions or methods. Within the humanities it is normal and perhaps reasonable enough to treat thinking as the domain of philosophy. There are indeed some kinds of thinking – consciousness, for example, or deliberation – where scientific experiments really have not got very far. Nonetheless, my inclination now is that assertions about ‘changing the way we think’ lend themselves to, and may require, empirical testing.

Any experiment into whether literature increases adaptive resilience in a changing world would have to work on a reductive scale, in comparison with Mack’s book. It could only define literary experience quite narrowly (a measured period of time spent in close consideration of a text; a threshold for how much time a given person spends reading outside the lab), and it could only represent adaptive resilience narrowly too: questionnaires, scenarios – it’s not exactly Cormac McCarthy. Nonetheless, for me at least, this would be a worthwhile check on Mack’s argument. This seems to me like a typical interdisciplinary tension, and one that’s partly addressed in Mack’s . It doesn’t seem over-ambitious to think that it could be resolved.

Caring for Ophelia

Last week I went to a workshop at the annual Royal College of Psychiatrists conference, organised by Neil Hunt, a consultant in Cambridge. They used Shakespeare’s Ophelia, in Hamlet, as a case study. Part of the focus of the event was on evaluating her mental state, and ascertaining signs of suicide risk, on the basis of the evidence in the text. Part of it, which I found particularly intriguing, was addressed to a coroner, defending the actions taken by the psychiatrist who treated Ophelia.

*

There is, of course, no psychiatrist in the play. However, one was ingeniously excavated from the text. Here is one familiar version of one key scene, taken from the 1623 First Folio edition:

QUEEN

I will not speake with her.

HORATIO

She is importunate, indeed distract,

Her moode will needs be pittied.

QUEEN

What would she haue?

HORATIO

She speakes much of her Father; saies she heares

There’s trickes i’th’world, and , and beats her heart,

Spurnes enuiously at , speakes things in doubt,

That carry but halfe sense: Her speech is nothing,

Yet the vnshaped vse of it doth moue

The hearers to ; they ayme at it,

And botch the words vp fit to their owne thoughts,

Which as her winkes, and nods, and gestures yeeld them,

Indeed would make one thinke there would be thought,

Though nothing sure, yet much vnhappily.

QUEEN

’Twere good she were spoken with,

For she may strew dangerous coniectures

In ill breeding minds. Let her come in.

The queen is troubled by Ophelia, and would rather avoid her. However, she senses that her madness may result from, and could reveal, dark secrets. Horatio, Hamlet’s friend, gives a perplexed but thoughtful description of her incoherent and persistent ramblings. It is likely that this version is revised from the different scene we see in the second quarto (1604):

QUEEN

I will not speake with her.

GENTLEMAN

Shee is importunat,

Indeede distract, her moode will needes be pittied.

QUEEN

What would she haue?

GENTLEMAN

She speakes much of her father, sayes she heares

There’s tricks i’th world, and hems, and beates her hart,

Spurnes enuiously at strawes, speakes things in doubt

That carry but halfe sence, her speech is nothing,

Yet the vnshaped vse of it doth moue

The hearers to collection, they yawne at it,

And botch the words vp fit to theyr owne thoughts,

Which as her wincks, and nods, and gestures yeeld them,

Indeede would make one thinke there might be thought

Though nothing sure, yet much vnhappily.

HORATIO

Twere good she were spoken with, for shee may strew

Dangerous coniectures in ill breeding mindes,

Let her come in.

Here a generic Gentleman reports on his observations of Ophelia, and it is Horatio, not Gertrude, who worries that she might cause suspicious minds to fester. In my Oxford text the editor G.R. Hibbard sees the Folio version as a piece of streamlining. A superfluous role is removed from the play. This seems fair enough, but the differences are consequential. Having Horatio rather than Gertrude fearing loose talk is quite a significant change; and missing out on the Gentleman’s contribution removes the idea that someone – perhaps with expertise – has been given the task of observing Ophelia.

At the conference workshop, a deft change was made: ‘Gentleman’ became ‘Doctor’. This gave the psychiatrists’ workshop a focus for their hypothetical consideration of a professional’s actions and their consequences in a legal framework. This is not entirely unwarranted. In Macbeth there is a palace doctor who witnesses Lady Macbeth’s night-time delusions, and reports upon them to her husband. The Hamlet scene represents a comparable situation, where it seems reasonable to think that the person entrusted with reporting on a sick individual might be qualified to do it.

But this is Elsinore, and this is Tragedy. The psychiatrists found ways of representing both points of view when presenting to the coroner. Ophelia was assessed, but nothing immediate was done: her behaviour wasn’t demonstrably consistent with suicide, and she was in a well-supported environment. On the other hand, the assessment was brief and perhaps inadequate, the patient evidently had disordered and morbid thoughts, and the care plan was too hands-off. Left in an unstable mental state in an impersonal and dysfunctional court, where nobody had shown her sufficient attention or sympathy thus far, it seemed all too predictable that Ophelia had killed herself, or at least put herself in danger.

*

A coroner (or ‘crowner’) is mentioned in Hamlet a little later. The gravediggers sardonically note that the official view is that Ophelia should have Christian burial – she has not committed suicide. They reason, all too plausibly, that her rank and connections must have helped. In the play, as for the psychiatrists, psychological judgments become entwined with legal judgments and social contexts. This might be one reason why considering Shakespeare’s plays seems productive to them. (There must be other reasons of course: the finite evidence, the need or chance to read between the lines, the sense of these narratives being realised and embodied in performance, the quality of psychological insight, the familiarity of the material, its status, its novelty, and so on…)

But the thing I came away thinking about most was care. There is a chilling lack of care for Ophelia. This is not just a judgment on characters, but also on the play itself. So little time is spent on her decline and her crisis. Everything seems to be consumed by Hamlet himself. This is how things are in Tragedy, perhaps, where nurses help you make fatal assignations and doctors cannot do anything to help. It is also the particular situation in which Ophelia finds herself, without anyone to support her.

The doctor-who-isn’t-a-doctor is either very astute or very lax. His main conclusion is that people draw conclusions from Ophelia that suit their own way of thinking. They ‘botch up the words fit to their own thoughts’. This is indeed what happens in Hamlet – to the hero himself when Polonius assumes he is mad for love, but Claudius thinks he is plotting to usurp him. Perhaps it’s a reflection on how difficult it is to interpret other minds on their own terms, even if you are supposed to be an expert. Then again, if we indulge the idea that this Gentleman should have something therapeutic to offer, this may just be a very unproductive medical opinion.

Motivated Forgetting (2)

In my previous post I wrote about evidence of neural activity apparently suppressing the storage and recall of unpleasant memories. This corroborates the idea that a tangible and ‘motivated’ forgetting complements the automatic kinds that are widely recognised: decay over time, interference between memories, and changed physical contexts removing crucial cues. In that post I suggested that literature, in spite of its more obvious role offering things to be remembered, might also involve things to be forgotten.

I offered two endings in Shakespeare’s plays where attention seems to be turned away from things that the characters, or the audience, might prefer to forget. More precisely, I think the plays offer opportunities for us to think about how forgiving might be a context in which motivated forgetting might be rather helpful. In these plays, if we actually cooperate in forgetting something discordant, we can be aware of ourselves doing it, if we want to.

In this post I would like to present one of Shakespeare’s Sonnets as an act of forgetting. These are complex poems in themselves, playing complex roles in a complex sequence. My proposition, in summary, is that (i) Shakespeare’s Sonnets are manifestly, explicitly, concerned with the memory of their main subject and recipient, a beautiful young man, and a lot of time is spent considering the poems themselves as the best form in which to create a memorial; that (ii) they challenge readers by not delivering that aim in a purposeful or consistent manner, fascinating but estranging us with repetitions, redirections, and contradictions; and that (iii) they may experiment with the possibility that the speaker might actually wish to remove this memory.

These posts are meant to be brief and there is so much to say about these poems, and more generally. So, although it probably does not need to be said, I feel the need to stress that I shall only be offering a partial reading of this sonnet:

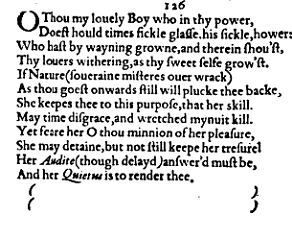

This is the very last of the ‘young man’ sonnets. The sequence seems to restart itself in the next poem, with a turn to the ‘dark lady’. Sonnet 126 argues that nature is protecting the young man and his beauty from time. In the end, in the final ‘audit’, he will be yielded, and Nature will eventually settle up (the point of ‘quietus’) with Time. The poem only has twelve lines, and the parentheses covering lines 13 and 14 have been discussed a lot: they are marks of omission, but we do not know whether they are taken from the manuscript poem, or a printer’s independent suggestion that there might be something missing. Sometimes people have wondered whether the 12th line seems to expect more – render thee what? It is suggestive to think of the blank as the product of the rendering or of a final and inevitable act of forgetting, the young man ending up as an absence in spite of so much effort in the poems. I think this reading is a bit forced, but it gets at the strange way these poems, so productive in some ways, have counter-productive turns.

As with the examples from plays in the previous post, the point might well not be that the poem forgets or makes us forget, but that it may be ‘about‘ motivated forgetting, about the need to shrug the shoulders, move on, restart, get on with life (or more poems).

2007), 331-342.

Motivated Forgetting

Michael C. Anderson and Simon Hanslmayr, ‘Neural Mechanisms of Motivated Forgetting’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18 (2014), 279-92.

It is widely agreed that we forget things because they decay over time, because memories interfere with one another, and because memories can be tied to physical contexts which, when removed, take the memory with them. This article assesses the evidence for more ‘motivated’ forgetting, whereby (for example) our brains work to make it harder for us to remember unpleasant experiences. They present evidence for neural activity (i) disrupting the representation and storage of these experiences in memory, and (ii) inhibiting their later retrieval. The lateral prefrontal cortex is especially associated with this means of ‘shaping the retention of our past’.

*

Literature might seem to be more about memory than forgetting. It stores representations of things, and it enables us to retrieve them under particular circumstances. Its many forms, devices, techniques, and strategies are mnemonic, then, in the ways in which they make both representation and retrieval more dynamic and appealing experiences. Things might slip away, but the effort aims at memory.

However, there may be circumstances in which literature investigates the need to forget, and performs or inculcates a sort of ‘motivated forgetting’. Anderson and Hanslmayr give an interesting list of ‘motives’ for doing this: regulating negative affect, justifying inappropriate behaviour, maintaining beliefs and attitudes, deceiving oneself and others, preserving self-image, forgiving others, maintaining attachment. Any of these might arise as part of, or in tension with, a literary work; it might be helpful, for example, to a scene of mercy, for a certain amount of forgetting to complement the forgiving.

*

I shall offer a couple of examples: first, the end of Measure for Measure. Amongst the various participants in the denouement, perhaps the strangest is the unapologetic criminal Barnardine. We have met him before, in prison, where he was (understandably, but inconveniently) unwilling to provide his own head to convince Angelo that the death sentence had been carried out on Claudio. In the last scene, head still attached, he gets drawn into the merciful mood. The Duke turns to him:

There was a friar told me of this man.

Sirrah, thou art said to have a stubborn soul.

That ,

And squarest thy life according. Thou’rt condemn’d:

But, for those earthly faults, I quit them all;

And pray thee take this mercy to provide

For better times to come. Friar, advise him;

I leave him to your hand.

The other acts of forgiveness in this scene are much more meaningful to an audience, and there are some difficult things to take on. Whereas the Duke says he will ‘quit’ at least the earthly crimes of Barnardine, forgiving him, he and the audience might need instead to forget him. He reminds us of the strange plotting that has only just averted disaster, and he reminds that amnesty saves the bad as well as the good. The friar is interesting: for much of the play the Duke himself has taken on this role in disguise. Perhaps the friar acts like activation in the lateral prefrontal cortex, preventing us having to store or re-address much about Barnardine.

*

And there’s something going on in The Winter’s Tale, which ends like this (with King Leontes, who has just had his wife and daughter restored to him after his earlier fits of destructive jealousy, speaking). If you hover your mouse over the highlighted words you’ll see me try to trace a process through the speech:

O, , Paulina!

Thou shouldst a husband take by my consent,

As I by thine a wife: this is a match,

And made between’s by vows. Thou hast found mine;

But how, is to be question’d; for I saw her,

As I thought, , and have in vain said many

A prayer upon her grave. I’ll not far –

For him, I partly know his mind – to find thee

An honourable husband. Come, Camillo,

And take her by the hand, whose worth and honesty

Is richly noted and here justified

By us, a pair of kings. Let’s from this place.

What! : both your pardons,

That e’er I put between your holy looks

My ill suspicion. This is your son-in-law,

And son unto the king, who, heavens directing,

Is troth-plight to your daughter. Good Paulina,

Lead us from hence, where we may leisurely

Each one to his part

Perform’d in this wide gap of time since first

We were dissever’d: lead away.

If this speech does perform a sort of motivated forgetting, it matters that we can see it happening. Leontes is trying to brush over things, perhaps with the best intentions. We can observe and assess this process as it happens in front of us, and possibly also to us at the same time. It may even be counter-productive: plenty of people remember Mamillius, the dead son of Leontes and Hermione, during these final moments. The King’s ‘haste’ might make us think more slowly. I do have my doubts about some aspects of the motivated forgetting article. Some of the things that my lateral prefrontal cortex is supposed to help with, past embarrassments especially, seem to come into my mind with alarming regularity. Perhaps the mechanism can backfire in reality as well as in fiction.

*

In future posts I hope to come back to this, to look at how motivated forgetting might be seen in other works. I would like to say something about lyric as well as drama; about something other than endings; and a bit more about what literature knows about this.