Coincidence and Curiosity: A Tale of Discovery in the Old Library at Queens’ College

First published April 2010

Karen Begg, Librarian, Queens’ College

|

A happy coincidence of scholarship and curiosity resulted in the recent discovery of three masterpieces of 14th century Italian manuscript illumination that for many years lay forgotten in a plan chest in the Old Library of Queens’ College. In 2007, when working on another project, Dr Stella Panayotova, Keeper of Printed Books and Manuscripts at the Fitzwilliam Museum, identified the pieces as the work of Pacino di Bonaguida, a prolific and distinguished Florentine artist. Since their identification, the miniatures have travelled the globe in a unique collaboration between the College, the Fitzwilliam and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, to learn more about the artist, his world and his techniques. As College Librarian, I am delighted to recount the Cinderella-like tale of discovery that has enabled a few more pieces of the ‘Pacino jigsaw’ to be fitted together and to report on a future for our miniatures that promises more than a return to the Library’s plan chest. |

||

|

The story begins with Stella’s visit to examine Dutch material for inclusion in the first volume of the Cambridge Illuminations catalogues [1]. Stella kindly agreed to glance at some cuttings that we knew little about, but suspected were of North Italian, early Renaissance origin. Stella excitedly and immediately shared her suspicions that these were lost leaves from a Laudario painted in Pacino’s workshop that she, together with other art historians around the world, had been researching. A laudario is a manuscript comprising lauds, or songs of praise in Italian that were used by lay communities to celebrate religious feasts or Saints’ days. The Queens’ leaves depict the Martyrdoms of St Christopher, St James the Great and St Lucy. The Fitzwilliam had been given two comparable leaves early in the 20th century and, coincidentally, had recently found a third – all from the same Laudario. Stella’s subsequent scholarly article on the Queens’ and Fitzwilliam leaves [2] summarises much of what is known about the artist and this Laudario, Pacino’s most renowned work, which is believed to have been commissioned by wealthy patrons for the Compagnia di Sant’ Agnese in Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence [3]. Stella describes in detail the content and context of each leaf and the art historical relevance of its discovery. |

||

|

During the next year, other specialists, including two experts from the Getty Museum, viewed our leaves and confirmed Stella’s opinion. In early 2009, Queens’ was invited by the Getty to take part in scientific research, the findings of which would feature in an exhibition planned for 2012 entitled “Florentine Painting and Illumination in the Time of Giotto”. This offered a unique opportunity to contribute to a significant and interesting study, and the College’s Governing Body unhesitatingly agreed to allow our manuscripts to travel to the Getty Museum, where non-invasive analysis of pigments and structure could be undertaken. |

||

|

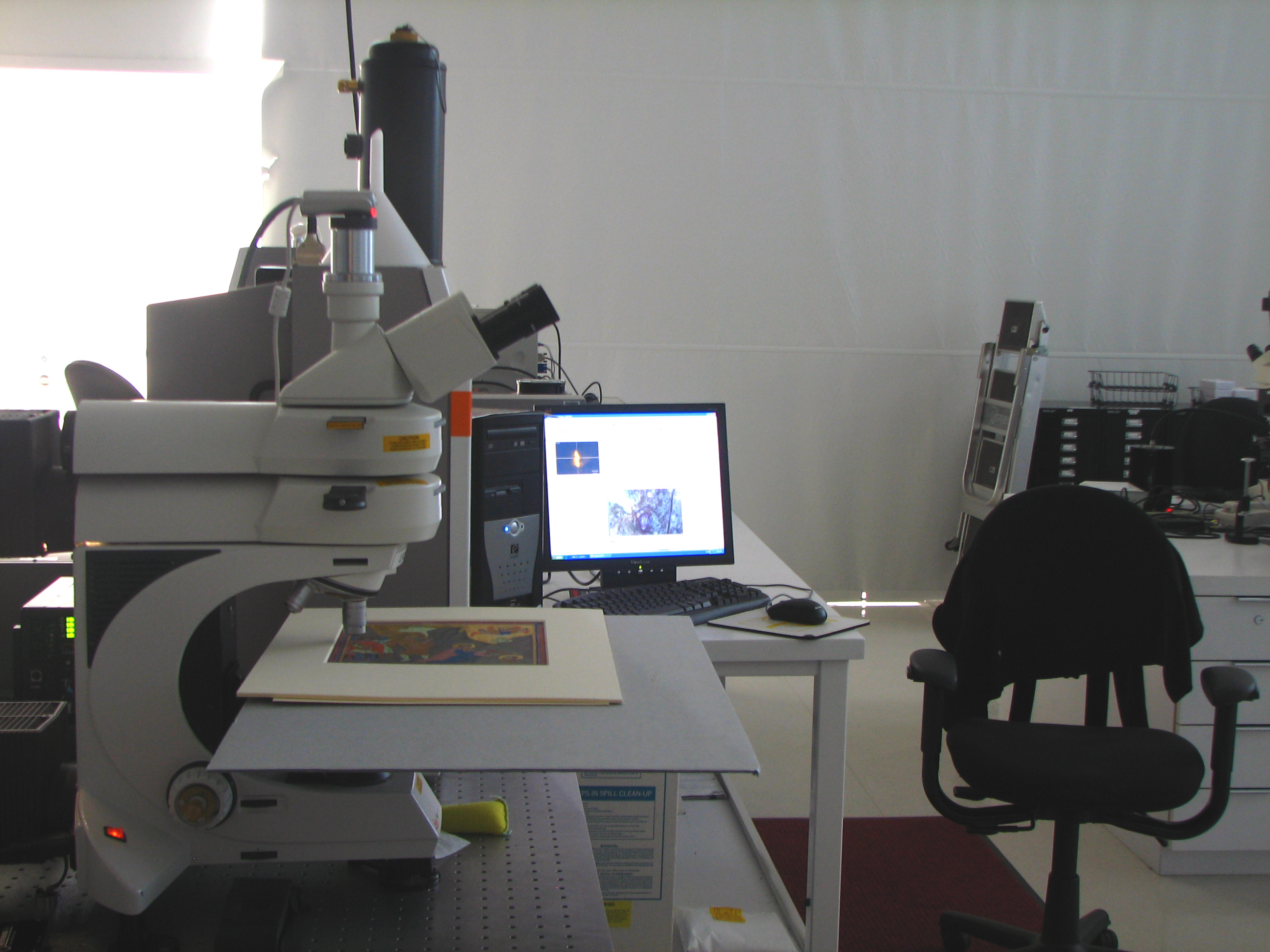

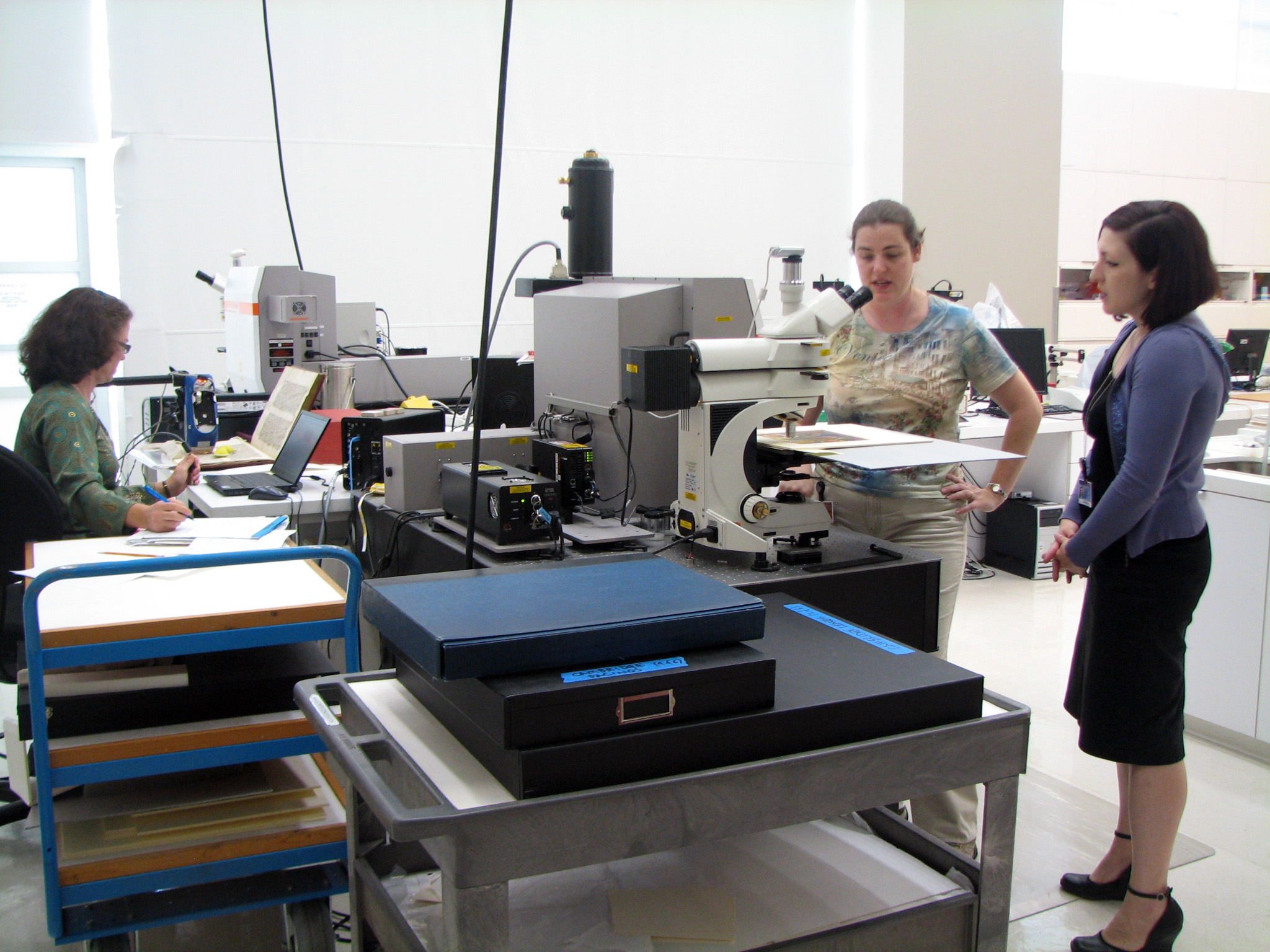

Plans were made for me to accompany the miniatures to Los Angeles in summer 2009 and review the analytical procedures. The arrangements took the College into new realms of legal discussion, as insurance agreements between us and the Getty had to take account of many risks, including the potential for ownership disputes. At this stage, the lack of provenance data for the cuttings’ arrival in Queens’ presented something of a problem, and conjured visions ranging from straightforward theft to claims of Nazi seizure. Fortunately, however, records confirmed their presence in College far enough back to dim this risk. It is worth noting though, that such unattributed acquisitions, perhaps long forgotten gifts, may now be financially as well as historically valuable, and the importance of acquisition records cannot be overemphasized. As planned, in July last year I took the miniatures to the Getty Museum, a stunning hilltop campus of gardens, galleries and terraces that commands panoramic views of Los Angeles and the North Pacific Ocean. I was welcomed by the curators, conservators and scientists of the Getty Museum and Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), who showed me around their conservation studio and laboratories, and demonstrated the state of the art equipment that would be used in the analyses. Their main objective was to “identify, characterize and compare the painting materials and techniques used by Pacino and his workshop” [4], particularly as previous investigation of the three Getty owned leaves had suggested the involvement of more than one artist’s hand, perhaps using a slightly different palette. This new study would widen the range of images studied, allowing direct comparison of nine of the 24 known surviving miniatures, and held the potential to reveal much about workshop practice of the 1340s. X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and Raman microspectroscopy would be used to identify pigments under drawings and techniques, without taking physical samples or touching document surfaces, and digital images would provide a visual record of findings. The Cambridge leaves returned to the UK in September 2009 and the research findings, some of which were presented at a National Gallery symposium last autumn, will soon be published. The techniques used can be seen in the images below, which have been reproduced with kind permission of the GCI. |

||

|

|

||

Figure 5. Image of the Raman setup for laser light excitation; the manuscript under analysis is Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 194. Image reproduced with kind permission of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. This image gives another view of the Raman spectroscopy setup, using 785nm laser light excitation. The manuscript is mounted on an easel, and the light is guided through the microscope and onto the leaf through the black arm. The entire configuration is non-contact. |

||

Figure 7. Another image of the Raman setup for laser light excitation; the manuscript under analysis is, again, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 194. Image reproduced with kind permission of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. This image provides a close-up Raman image of MS 194, showing the laser spot as a yellow dot on the manuscript. Much more is expected to emerge from this collaboration between several quite different institutions. In addition to the publications in preparation, we look forward to taking part in the 2012 exhibition, for which the Cambridge miniatures will once again travel to Los Angeles. Meanwhile, the three Queens’ College Pacinos will soon relinquish their plan chest for a new home in the Founder’s Library at the Fitzwilliam Museum. The generosity of a number of College alumnae has enabled Queens’ to offer them on long term loan to the Museum, where they will be accessible to scholars and available for public display in a way which is not possible in the College Library. The Fitzwilliam will be able to store them with their own Pacino leaves in an environment that celebrates their significance and beauty as early Renaissance works of art. |

||

Notes

[1] Nigel Morgan and Stella Panayotova, A Catalogue of Western Book Illumination in the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Cambridge Colleges. Part 1, Vol.1. Harvey Miller Publishers, London 2009.

[2] Stella Panayotova, ‘New Miniatures by Pacino di Bonaguida in Cambridge’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. CLI, n. 1272, March 2009, pp. 144-147.

[3] R. Offner, A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century, Section 111, vol. VII, New York 1957.

[4] Unpublished Proposal for the Technical Analysis of Queens’ College, Cambridge MSS 77B, 77C, and 77D , submitted to Queens’ College by the J. Paul Getty Museum, March 2009.