Eating Words: Text, Image, Food

September 30th, 2012

The main event hosted by the Centre this year was a one-day colloquium entitled ‘Eating Words: Text, Image, Food’, which took place in Gonville and Caius College on 13 September 2011. The colloquium, organized by Melissa Calaresu and Jason Scott-Warren, set out from the observation that the text that can be eaten, or that accompanies eating, might be thought to represent writing at an extreme of materiality. Nonetheless, we readily use words and images associated with eating to describe processes of reading and writing. The colloquium brought together an international line-up of literary scholars and historians of food with the aim of understanding the peculiar confluence of metaphor and materiality that flavours so many of our dealings with the word—whether written or spoken, swallowed or angrily spat out.

The main event hosted by the Centre this year was a one-day colloquium entitled ‘Eating Words: Text, Image, Food’, which took place in Gonville and Caius College on 13 September 2011. The colloquium, organized by Melissa Calaresu and Jason Scott-Warren, set out from the observation that the text that can be eaten, or that accompanies eating, might be thought to represent writing at an extreme of materiality. Nonetheless, we readily use words and images associated with eating to describe processes of reading and writing. The colloquium brought together an international line-up of literary scholars and historians of food with the aim of understanding the peculiar confluence of metaphor and materiality that flavours so many of our dealings with the word—whether written or spoken, swallowed or angrily spat out.

The conference opened with a session on ‘Culinary Technologies’. Helen Smith (York) brought a rich blend of intellectual influences (Wendy Wall on kitchen literacies, Michel de Certeau on the ancient tricks at work in the scientific laboratory, Bruno Latour on hybrid man-machine organisms) to bear on the accounts of printing in Joseph Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises (1683). Examining his references to the use of foodstuffs such as salad oil in the printing house, she suggested that the domestic and typographic arts were close kin. Emma Spary (Cambridge) followed this up with an exploration of the mysteriously eleborate preface to a rather commonplace cookery book entitled Les Dons de Comus ou les Délices de la Table (1739). This fine sauce to vile meat was suspected by many to have been penned by Voltaire, and sparked a controversy about the proper language for the dissemination of culinary knowledge. Was cookery a ‘scientific’ subject, or some species of fine art? Or were such notions made to be ridiculed? Spary ended with a call for food historians to be more attentive to the satirical and parodic motives lurking in apparently straight-faced works.

The second morning slot was divided between two parallel sessions. The first, ‘Cookbooks and Method’, got stuck into the difficulties of thinking about cookery books as a genre. The two papers were sharply contrasted. Divya Narayanan (Virginia) surveyed a variety of Indo-Persian manuscripts, many of which survive in several richly-illuminated exemplars, and the texts of which defy dating. Highly diverse in terms of their documenting of ingredients, their interest in matters of health and deportment, and their representation of patrons and connoisseurs, these manuscripts offer an insight into past culinary cultures whilst posing many insoluble questions of origin, transmission and audience. Nathalie Parys (Brussels) set out the methodology of her doctoral project on nineteenth- and twentieth-century Belgian and Dutch cookery books, defined very firmly as books that dealt only with food. Parys’s database will offer a longitudinal survey of what people thought they ought to be cooking and eating, and will survey changing trends in the categorization and naming of recipes.

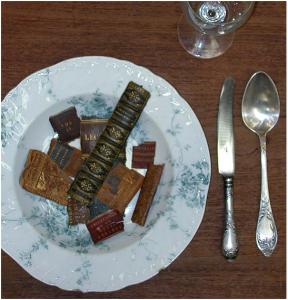

In the concurrent session, entitled ‘Studies in Bibliophagy’, the speakers discussed brilliant but strange artworks that take the book-eating metaphor literally. Tammy Ho Lai-Ming (KCL) talked about Tom Phillips’s A Humument, a book (and now an app) that ingests or cannibalizes a Victorian novel, by painting over and otherwise manipulating its text in order to discover a new, fragmentary narrative within it. This, she proposed, provides a model for a class of neo-Victorian novels that consume their precursors as they come into being. Gill Partington (Birkbeck) described the conceptual artist John Latham’s experiments in book eating (and book-burning) in the 1960s. One of these resulted in the reduction of a printed book to a semi-digested pulp; a dispute with a library; and the artist’s dismissal from his job.

In the concurrent session, entitled ‘Studies in Bibliophagy’, the speakers discussed brilliant but strange artworks that take the book-eating metaphor literally. Tammy Ho Lai-Ming (KCL) talked about Tom Phillips’s A Humument, a book (and now an app) that ingests or cannibalizes a Victorian novel, by painting over and otherwise manipulating its text in order to discover a new, fragmentary narrative within it. This, she proposed, provides a model for a class of neo-Victorian novels that consume their precursors as they come into being. Gill Partington (Birkbeck) described the conceptual artist John Latham’s experiments in book eating (and book-burning) in the 1960s. One of these resulted in the reduction of a printed book to a semi-digested pulp; a dispute with a library; and the artist’s dismissal from his job.

The morning ended with the first of the day’s plenary speakers, Deborah Krohn (Bard Graduate Center). Krohn is currently completing a monograph on the first illustrated cookery book, Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera dell’arte del cucinare (printed in numerous editions between 1570 and 1643). This was a work that first caught her eye as a historian of art, but this paper was absorbed with the question of book use, and with making sense of one particularly densely-annotated copy of the Opera. The reader of this copy customized the index and added numerous marginalia, including cross-references to recipes that employed similar ingredients or that led to similar results (the reader had an evident fondness for polpette, or meatballs!). In sum, he thoroughly masters (or digests?) Scappi’s text. Drawing attention to the division of labour between stewards and cooks in Italian elite households, Krohn suggested that the reader of this volume belonged to the former group. The book would never have been present in the kitchen, but was part of the broader management of the household.

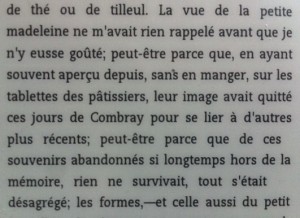

One of the two afternoon sessions, entitled ‘Mealtimes’, ranged widely across time and space in search of ingredients. Tessa Webber (Cambridge) explored the practice of reading during meals in monasteries—a practice established, according to one monastic commentator, to prevent the idle chatter and dissension that inevitably arises when people come together to eat. Another spur came from the practical demands of the annual cycle of reading, which could not be completed in the time afforded by the Mass and the Night Office (Matins), and so spilled over into the refectory. The practical demands of juggling saints’ lives, patristic commentaries and gospel homilies, sections of which were read at different times in different parts of the monastery, were considerable, as is evidenced in the margins of the weighty volumes that survive. Sara Thornton (UCL) then shifted the focus from reading to writing, looking at the use of foodstuffs (and in particular jam and pickles) in novels and short stories by Henry James. James on one occasion distinguished directly between those fictions that the public swallowed down like children wolfing jam and those (like his own) that were deemed harder to swallow. In her subtly nuanced account, Thornton argued that James’s dealings with food were frequently characterized by greater or lesser degrees of abstraction, and that jam and pickles figured for their ancillary, supplementary quality, their ability to play (like the writer) teasingly around the edges of food’s materiality. Supplementation was also at issue in the final paper of the session, as Ruth Cruickshank (Royal Holloway) took us into the entanglement of two phenomena often thought of as quintessentially French—cooking and literary theory. After an introduction surveying the significance of the residual, the undigestible and the ‘leftover’ in theory, her paper focused on Barthes and Lévi-Strauss. Cruickshank showed how their celebrated analyses of eating have their own leftovers or blind-spots resulting from the repressed traumas of twentieth-century French history.

One of the two afternoon sessions, entitled ‘Mealtimes’, ranged widely across time and space in search of ingredients. Tessa Webber (Cambridge) explored the practice of reading during meals in monasteries—a practice established, according to one monastic commentator, to prevent the idle chatter and dissension that inevitably arises when people come together to eat. Another spur came from the practical demands of the annual cycle of reading, which could not be completed in the time afforded by the Mass and the Night Office (Matins), and so spilled over into the refectory. The practical demands of juggling saints’ lives, patristic commentaries and gospel homilies, sections of which were read at different times in different parts of the monastery, were considerable, as is evidenced in the margins of the weighty volumes that survive. Sara Thornton (UCL) then shifted the focus from reading to writing, looking at the use of foodstuffs (and in particular jam and pickles) in novels and short stories by Henry James. James on one occasion distinguished directly between those fictions that the public swallowed down like children wolfing jam and those (like his own) that were deemed harder to swallow. In her subtly nuanced account, Thornton argued that James’s dealings with food were frequently characterized by greater or lesser degrees of abstraction, and that jam and pickles figured for their ancillary, supplementary quality, their ability to play (like the writer) teasingly around the edges of food’s materiality. Supplementation was also at issue in the final paper of the session, as Ruth Cruickshank (Royal Holloway) took us into the entanglement of two phenomena often thought of as quintessentially French—cooking and literary theory. After an introduction surveying the significance of the residual, the undigestible and the ‘leftover’ in theory, her paper focused on Barthes and Lévi-Strauss. Cruickshank showed how their celebrated analyses of eating have their own leftovers or blind-spots resulting from the repressed traumas of twentieth-century French history.

The parallel session, ‘Banquets of Words’, kicked off with Raphael Lyne (Cambridge) on the tendency of classical and early modern literary texts to describe themselves as foodstuffs. Macaronic poetry, mixing lines of Latin and vernacular languages, was named after macaroni; the pastiche was named after the pasticcio, a mixed rustic dish; even the satire seems to take its name from a stew. Speculating that the metaphorics of eating words were an example of what George Lakoff calls ’embodied metaphor’, which explains a comparatively distant and complex phenomenon (reading) in terms of the more comprehensible and close-to-home (eating), Lyne proposed that these literary foodstuffs owed their existence to their perceived indigestibility, illustrating his case with reference to Thomas Nashe (supposed author of An Almond for a Parrat [1590]) and Thomas Coryate (writer of Coryates Crudities: Hastily Gobbled up in Five Moneths Travells [1611]). His paper was followed by Erin Weinberg (Queen’s, Canada) on the numerous stomach-turning foodstuffs of Shakespeare’s play Titus Andronicus (printed 1594), from the sizzling human entrails of Act One to the cannibalistic meat-pie of Act Five. Weinberg was particularly interesting on the way in which eating might function metaphorically within the play, as more and more of its characters are consumed by the desire for revenge. Finally we heard Elizabeth Swann (York) on the notion of taste embedded in the commonplace early modern image of the good reader as a bee who sucks honey from the garden of literature. Her paper included a fascinating discussion of the imagined relationships between the composition of ink (made, in part, from the ‘galls’ that grow on oak-trees) and the humours (including the ‘gall’ produced by the gall bladder) that determined the physiology of the human body.

In the concluding plenary, Sara Pennell (Roehampton) considered how the pre-modern English kitchen might have furnished a stage-set for ‘lived religion’-the practice of piety in everyday life. Her exploration of probate inventories suggested that the kitchen was a significant locale for the keeping of Bibles and other devotional manuals; meanwhile, puritan life-writings suggested how readily providential interpretations could be attached to humble domestic accidents (when a chopping board fell from a high shelf without hurting anyone, God’s hand was visible in the world). Religion was powerfully instantiated in the numerous interlocking cycles of feast and fast, and it was rendered visible in a host of images on wall-tiles and firebacks, pan-handles and prints. Even the salt had apotropaic qualities. Drawing on fragmentary, often recalcitrant evidence, Pennell painted a compelling picture of the kitchen as a sphere inscribed with religious significance.

In the concluding plenary, Sara Pennell (Roehampton) considered how the pre-modern English kitchen might have furnished a stage-set for ‘lived religion’-the practice of piety in everyday life. Her exploration of probate inventories suggested that the kitchen was a significant locale for the keeping of Bibles and other devotional manuals; meanwhile, puritan life-writings suggested how readily providential interpretations could be attached to humble domestic accidents (when a chopping board fell from a high shelf without hurting anyone, God’s hand was visible in the world). Religion was powerfully instantiated in the numerous interlocking cycles of feast and fast, and it was rendered visible in a host of images on wall-tiles and firebacks, pan-handles and prints. Even the salt had apotropaic qualities. Drawing on fragmentary, often recalcitrant evidence, Pennell painted a compelling picture of the kitchen as a sphere inscribed with religious significance.

This intellectual feast was preceded on the evening of 12 September by an experiment in book-eating at Plurabelle Books, courtesy of Michael Cahn (visual evidence at http://plurabellebooks.blogspot.com/2011/09/eat-that-book.html). The day was rounded off by a dinner which began with alphabet soup and continued in the same vein through to dessert—thanks to the efforts of the Caius chef and Lucy Razzall, who also provided numerous highly literate sweet treats (including fortune cookies and cakes topped with love-hearts) throughout the day. Thanks also to Harriet Phillips for her help with administration.