After the death of playwright Harold Pinter on Christmas Eve, 2008, the Guardian published the last interview he had given, earlier that year, with one of the paper’s journalists. Pinter spoke from his London home, mainly about one of the great passions of his life: cricket. Recalling the occasion, Andy Bull describes Pinter’s study as ‘heavy with the clutter of a cricket fan’, with shelves which ‘creaked under his cricket library, including all 145 editions of the Wisden Almanack’. As Bull points out, the appeal of cricket to one who writes plays is palpable, in its ‘endless potential for narrative, the games within a game’. Today the British Library revealed that those weighty Wisdens turned out to play a crucial role in another narrative – that of an important new acquisition of letters written by Pinter between 1948 and 1960. Sent to friends when Pinter was a young man, none of the letters came with a date, presenting a significant problem for the Library’s curators. But Pinter’s love for cricket – what he once described as ‘the greatest thing that God created on earth’ – is manifest throughout them, and his frequent cricketing references became invaluable clues. The curators cunningly matched these up with the details in Wisden volumes to identify dates for the letters, in an enviably neat synthesis of epistolary remains and contemporaneous material texts.

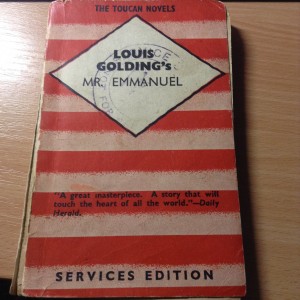

This unusual paperback novel caught my eye recently (and most serendipitously, on a shelf of free books in a railway station waiting room! I’ll leave something in its place when I’m next there…). This copy of Mr Emmanuel is a special ‘Services Edition’, produced for the Services Central Book Depot in London, for distribution to the Allied Forces. Although I’ve found a lot of information about a similar scheme in operation in the USA during the 1940s (the American Armed Services Editions), less has been written about the story of books like this one. There are some avid collectors, and this photograph from Getty Images shows great piles of books in preparation at the Depot, in 1944.

The book is printed on very thin paper, in a size surely intended to fit the pocket of a uniform, and the pages are held together with two sturdy metal staples. Golding’s novel, about a Russian Jewish refugee who travels from England to Germany, was originally published in 1938, and made into a film in 1944, and so this would have been distinctly topical and contemporary reading matter when it was sent out to the Forces in the 1940s. In several ways, then, it’s a markedly ephemeral text, and I wonder how many others like it have survived.

Here’s a holiday snap from northern France: a carved stone panel showing the four evangelists, from the mid sixteenth century. While it’s common to see the writers of the gospels holding books and accompanied by their symbols (from L-R here: Mark with a winged lion, John with an eagle, Luke with a winged bull, and Matthew with an angel), I was struck that this panel depicts all four of them caught in the very act of writing. Matthew (whose gospel was for a long time believed to be the earliest) balances a scroll on his knee, while the angel holds up his ink pot. Luke makes use of a lectern and the other two work with much more compact-looking codices. The carver included scroll flourishes behind each figure – and if the panel was once polychromed, presumably they bore words which could be read.

A few weeks ago I made a pilgrimage to Great Yarmouth – not, as fellow early modernists might suspect, in the footsteps of Thomas Nashe, but on the trail of a temporary exhibition at the town’s Time and Tide Museum. Frayed: Textiles on the Edge brought together a poignant collection of historic and contemporary textiles associated with personal experiences of suffering. These pieces were framed as the work of outsiders – people ‘on the edge’ in some way. But – created by individuals whose circumstances kept them in a workhouse, prison, or hospital, or who were isolated by grief or mental illness – they were also the products of the experience of confinement, of being physically or mentally locked inside.

Several of the exhibits were sorrowful works of memoriam, a reminder that in previous centuries, the death of a child was much more common, and no less painful. Anna Brereton, the maker of a patchwork counterpane and bed hangings in the eighteenth century, must have been in an almost permanent state of recent bereavement, losing four children in their infancy, and her eldest son at the age of fourteen. As some of the other pieces revealed, the reality of death was known from a young age and like adults, children also marked out their grief in stitches. There was a sampler which had been started in 1833 by a little girl called Martha Grant, and finished the following year, probably by her sister, after Martha died at the age of eleven years. Between 1823 and 1829 another young girl, Louise Buchhotz, made three small samplers, each stitched in black thread, to mark the deaths of her parents and uncle. ‘For since she’s dead, for ever gone/ O GOD my soul prepare/ To enter into heavens high gates/ In hope to meet her there’, she stitched in memory of her mother, on a tiny piece of pale linen no bigger than a page of a pocket-sized book.

In an understated way, Frayed challenged typically gendered narratives of stitching in which embroidery is thought of as a solely female occupation. I did not know that after the second world war, manufacturers of embroidery silks set up ‘Needlework for H.M. Forces’ schemes, supplying recuperating soldiers with kits to ‘help relieve the inevitable boredom of idle hours’, and give ‘the satisfaction that arises from the practice of personal skill’. Relief from boredom and satisfaction at creating something beautiful out of the horrors of the past must have in part motivated John Craske, the maker of a large woolwork tapestry depicting the evacuation of Dunkirk. Craske spent long periods recovering from physical and mental illness following military service in the first world war, but poignantly, the piece is unfinished, for he died in hospital in 1943. The contemporary tapestry cushions made by men in prison through the social enterprise Fine Cell Work demonstrated that the therapeutic value of stitching for everyone, but especially those in confined conditions, is still taken seriously today.

The therapeutic value of stitching was painfully evident in another piece, loaned for the exhibition from the V & A. Elizabeth Parker’s sampler was made around the year 1830, by a woman who worked as a nursery maid and endured cruel treatment from her employers. In letters worked in tiny red cross-stitches on linen cloth, she set down a confessional account of ‘that willful design of selfdestruction’ which tormented her. Scripture providentially helped her out of the darkness: ‘the Bible lay upon my shelf I took it down and opened it the first place that I found was the fourth chapter of S. Luke where it tells how our blessed Lord was tempted out of Satan I read it and it seemed to give me some relief for now’. Her own writing stops mid-sentence, however – ‘What will become of my soul’ – leaving nothing else but the remaining blank space of her linen page.

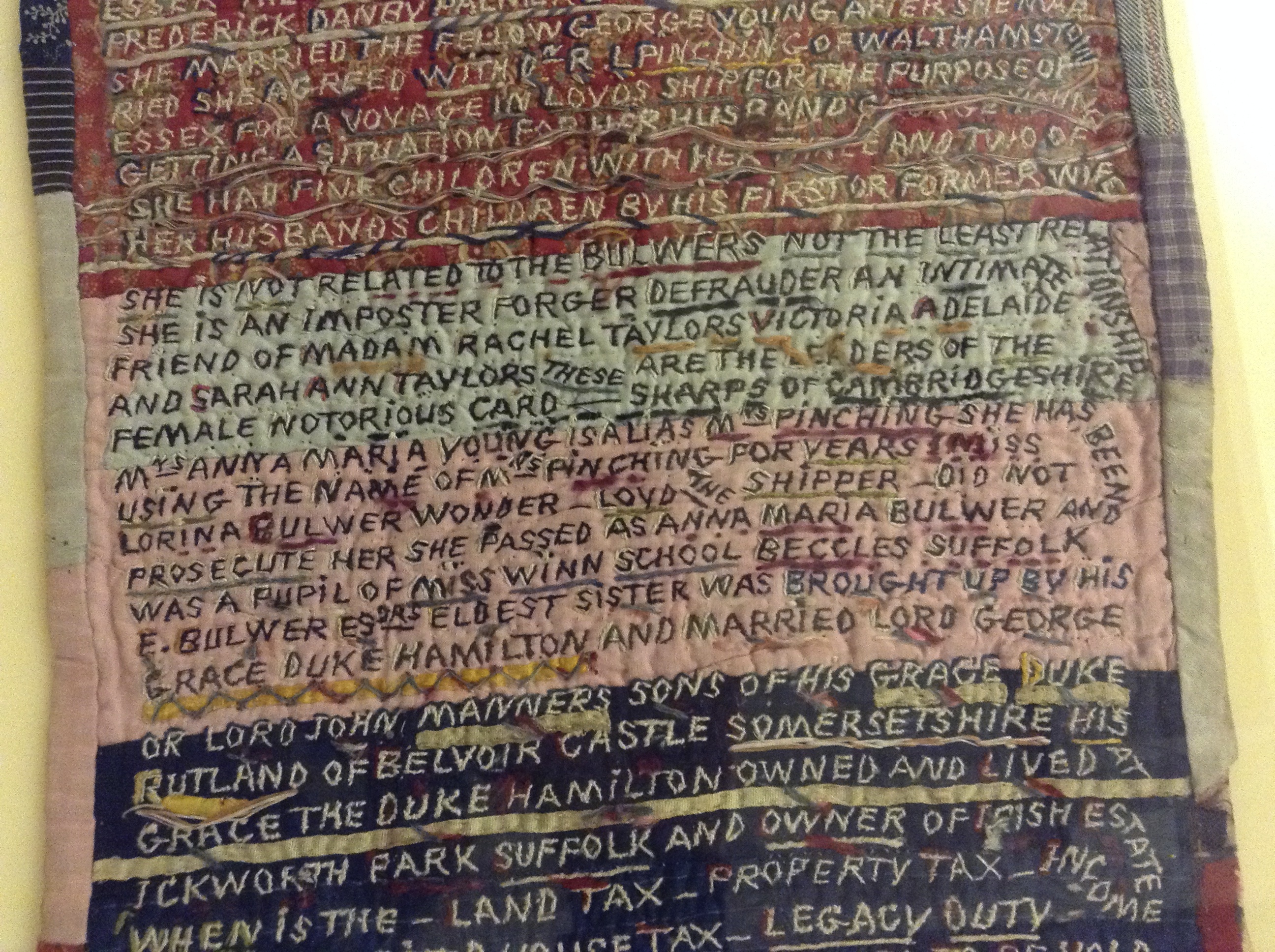

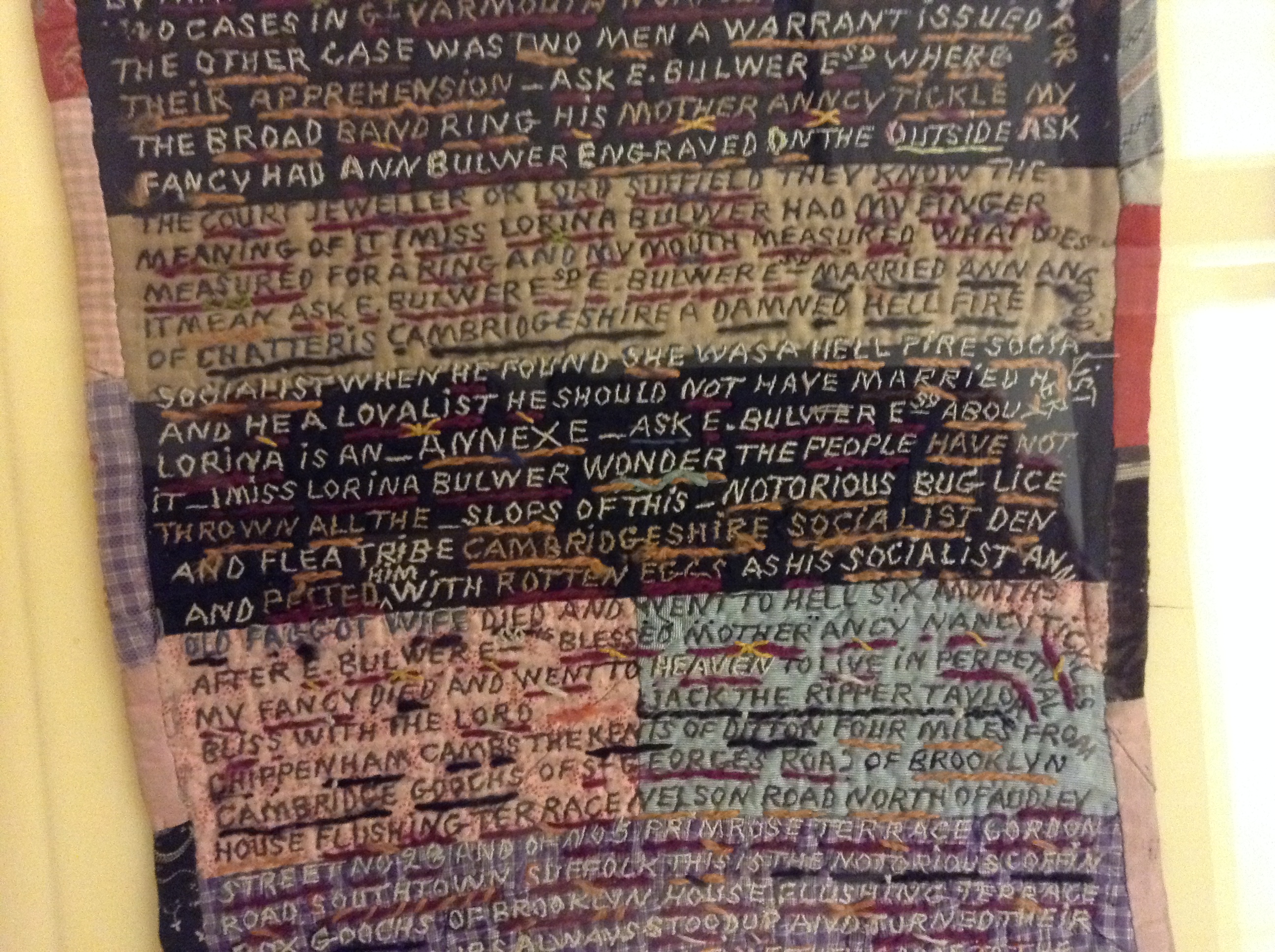

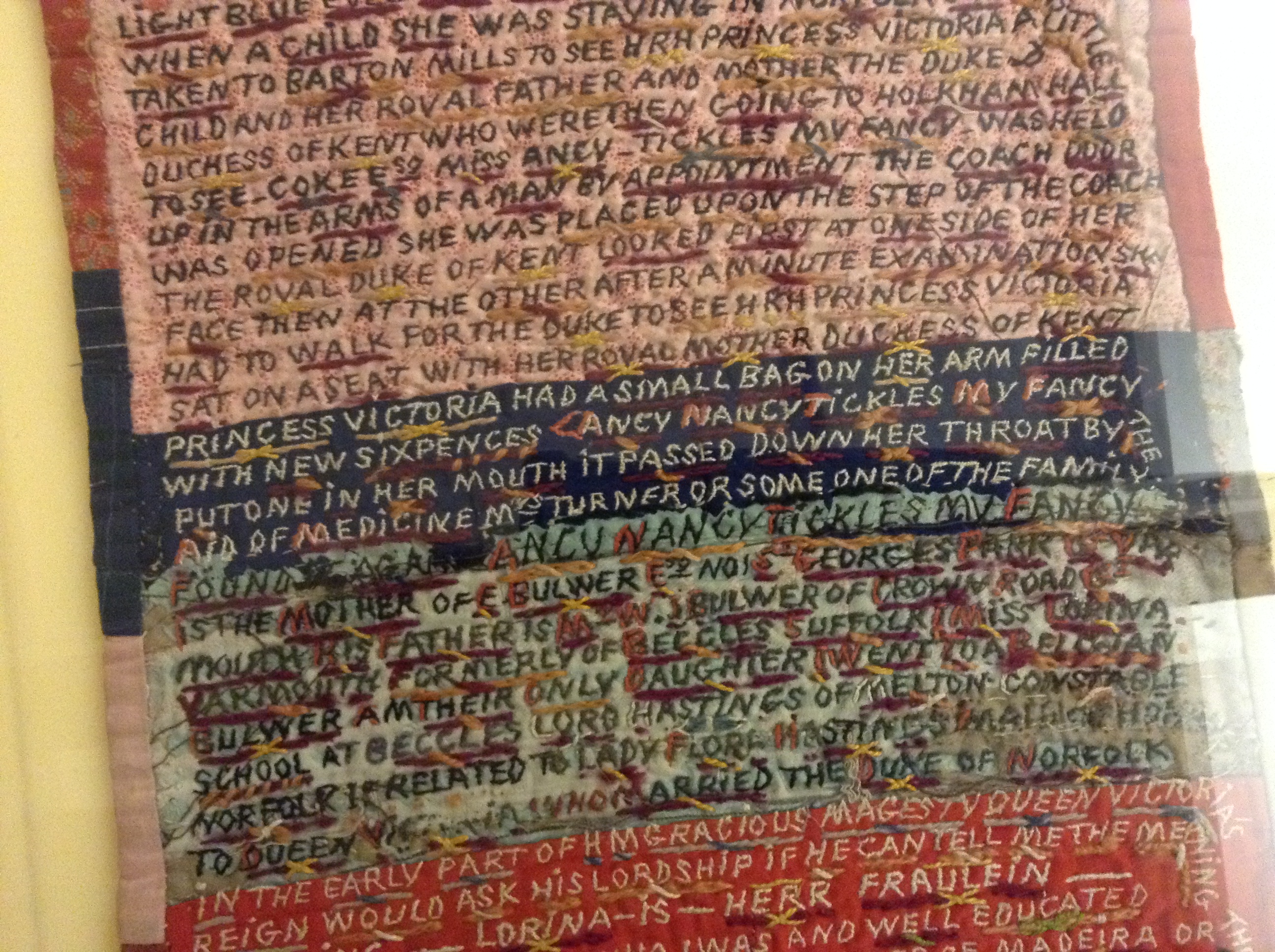

At the centre of the exhibition were two truly extraordinary stitched texts (pictured above and below) by a woman called Lorina Bulwer, who was an inmate in the ‘lunatic wing’ of the Great Yarmouth workhouse for several years at the beginning of the twentieth century. During her time there, Bulwer covered each of these three-metre lengths with densely embroidered text in which she expressed feelings of anger and frustration. Both pieces are made up of brightly coloured cotton fabrics stitched together, with a wadded lining and a backing fabric, like a quilt. Each individual letter is stitched through all of these layers. Writing in the first person, Bulwer offers a torturous working-out of her own identity. She is obsessed by names and places, frequently referring to herself by name, as well as to other people, including her own relations, members of the Royal family (she claims to be ‘Princess Victoria’s daughter’), and various towns and places in the East of England. A disturbing tangle of visceral, furious commentaries on people and situations apparently significant to her, Bulwer’s texts are impossible to summarise, but you can read transcriptions of them here.

The overall effect is one of unsettling, febrile tension between the text and its textile medium. Bulwer’s words are undoubtedly a rant, composed entirely in capital letters and without any punctuation – but their manifestation on the ‘page’ is the result of a slow process, in which each stitch has been individually formed. Writing with a needle is much slower than writing with a pen – another exhibit, Sara Impey’s machine-stitched contemporary quilt, made this point explicitly: ‘THE MOST DEMANDING ASPECT OF STITCHING IS TIME. THE STITCH DICTATES THE PACE’. Time, of course, is the one resource that imprisoned people, like Bulwer, often have most readily to hand. In her work, however, the inherently time-consuming, careful method of material composition contrasts with the angry, breathless quality of her words. It is clear that Bulwer intended her work to be read: she changes the colour of her thread according to the colour of the background so that the text is always clearly defined, and often highlights individual letters in contrasting thread where they cross over two different background colours. She underlines almost every word, and sometimes continues the text at right angles, along the borders. The cheery colours of the threads and background sit uneasily with the apparent bleakness of her experiences, and her implications of abuse. Bulwer’s desire to communicate is very evident, but this exhibition was the first time that both pieces have been displayed together (they are held in two different museum collections) – a sign, perhaps, of a general uncertainty about exactly how to read them.

Frayed: Textiles on the Edge has now ended, but the Time and Tide Museum (shortlisted for the Council of Europe’s Museum of the Year in 2006) is definitely worth a visit.

Wardrobe advice from the Guardian last weekend: ‘text has never been so fashionable’. Speculating that ‘perhaps it’s a spin off from watching subtitled Scandi dramas that these days we feel hip and culturally on-point if we’re looking at words’, the columnist finds herself no longer quite so opposed to jumpers emblazoned with a message, or, ‘a speech bubble in knitwear form’…

In the most recent episode of the BBC’s Call the Midwife (a drama about a community of nursing nuns in the East End in the 1950s, based on the memoirs of Jennifer Worth), we learn that the eccentric Sister Monica Joan, now in her nineties, maintains a small personal library. The amount of time she spends tending to her ‘repository of knowledge’ (including rebinding volumes with leather and paste, and ripping the ‘heretical’ pages of the Apocrypha out of a Bible) is the cause of much frustration for the indomitable Sister Evangelina, who mutters ‘Never been a reader. Always been a doer’. Arranging her books on makeshift shelves, Sister Monica Joan complains that ‘the Dewey Decimal System is altogether too earthbound, and likely to speak loudest to pedantics’ – and instead she puts volumes by Astley Cooper and Rousseau next to each other, so that they can converse, while ‘Plato and Freud can be companions in their ignorance’. All of this playing with books is intended, as is usually the case with Sister Monica Joan’s especially eccentric moments (she is getting dementia) for bittersweet comic effect. However, contrary to Sister Evangelina’s suspicions, ‘reading’ turns out to be ‘doing’, too. In the main storyline, two young brothers are very sick, and the doctor cannot find a diagnosis for their mysterious symptoms. Noone has an answer other than the old-fashioned catch-all of ‘failure to thrive’, until Sister Monica Joan hears about it and runs through the rain in the night to give the doctor a book from ‘the reign of Queen Anne’, from her collection. I’m not sure what this book was, but it leads him to diagnose the two children with cystic fibrosis (in the 1950s, this had only recently been identified as a genetic condition). The elderly nun is vindicated, for she spoke truth in her perceived madness, and as the episode came to a close, it was pleasing to see that she was given a proper bookcase for her precious volumes.

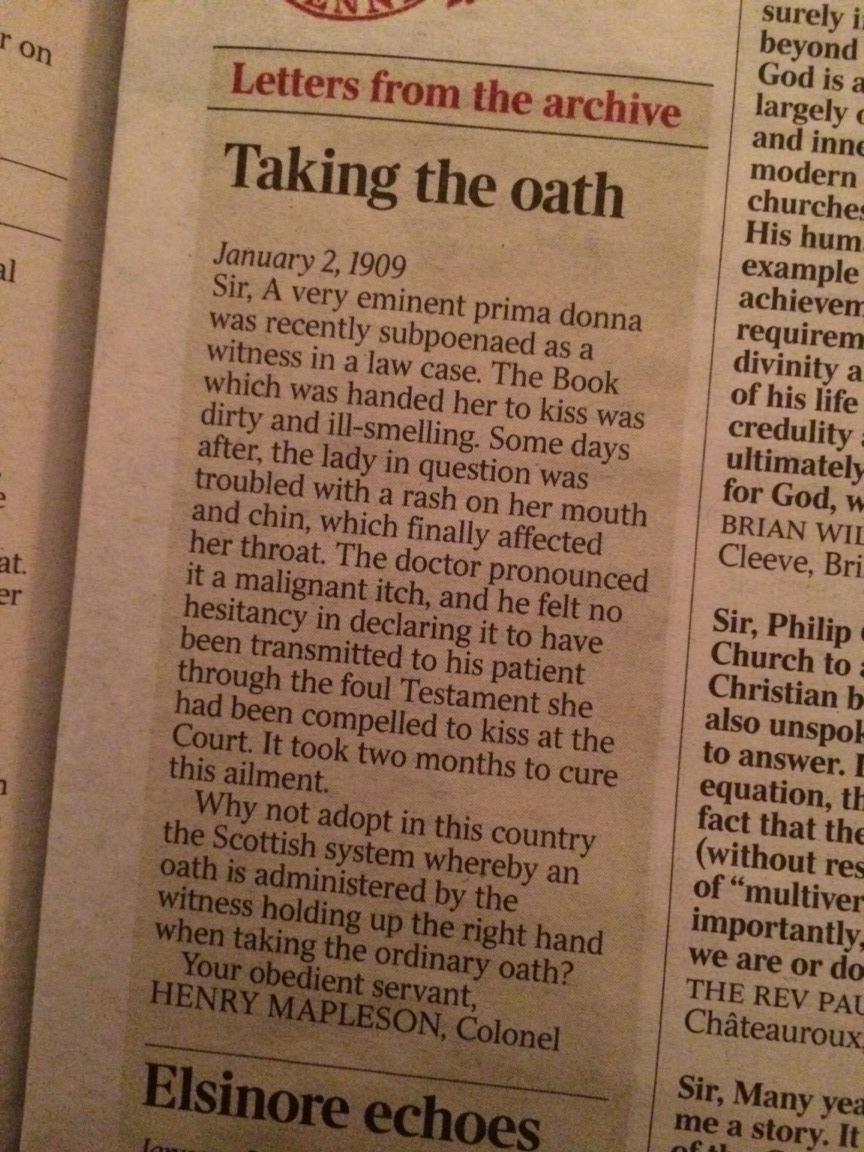

One of the broadsheets found in their archive this sorry story of a witness in a law case and the ‘foul Testament’ from which she contracted a ‘malignant itch’ after kissing it by way of swearing her oath. While a certain ’eminent prima donna’ of our own times has met with other troubles after her recent appearance as a witness in a high-profile trial, she has at least avoided this troublesome complaint. The original correspondent would be pleased to know that kissing the Book is no longer necessary in Court…

One of the broadsheets found in their archive this sorry story of a witness in a law case and the ‘foul Testament’ from which she contracted a ‘malignant itch’ after kissing it by way of swearing her oath. While a certain ’eminent prima donna’ of our own times has met with other troubles after her recent appearance as a witness in a high-profile trial, she has at least avoided this troublesome complaint. The original correspondent would be pleased to know that kissing the Book is no longer necessary in Court…

I learnt a lot from another current exhibition at the Huntington, about the man sometimes called the ‘founding father of California’. ‘Junipero Serra and the Legacies of the California Missions’ coincides with the 300th anniversary of the birth of the Franciscan priest who journeyed in the mid-1700s from the Spanish island of Mallorca to Mexico, and then up to California, where he established a series of missions for the conversion of the native Indians to the Catholic faith.

Curated by Steven Hackel and Catherine Gudis, this tremendous exhibition paints a very complex picture of the relationships between the region’s diverse Indian communities and the Franciscans who ran the missions throughout the eighteenth century and beyond.

Many of the 250+ artefacts (from the Huntington’s collections, and loaned from an impressive number of other places as well) in the exhibition were intriguing material texts – some of the numerous letters Serra wrote to fellow priests in Mexico, and to his family back in Spain; a woodblock supposedly used by Serra to print religious sheets for distribution in the streets; rare surviving written examples of a few of the more than one hundred languages spoken by the Indian communities. One of the really striking things was the bureaucratic efficiency of the Franciscans in charge of the missions, who documented every baptism, marriage, and burial. As the curators are careful to point out, these records would have been for Serra and his colleagues a glorious accounting of souls saved, but they can also be read as a terrible toll of mission life on Californian communities: disease, for example, brought untimely death to thousands of Indians. The surviving records have been collated in the Early California Population Project.

All Californian schoolchildren learn about Junipero Serra today, and this remarkable exhibition attempts to complicate some of the traditional narratives around this figure, emphasising the rich range of responses of the Indians to the missionaries. The curators also stress the ways in which both the Indian and Spanish pasts have been romanticised – through the ‘mission revival’ architectural fashions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the evolution of the missions into tourist attractions, for example. Another material text chosen for the exhibition speaks of this tendency to mythologise California’s complex past: in 1967, Ronald Reagan was sworn into office as Governor of the state with a bible thought (though nobody can be sure) to have been used by Serra.

The exhibition continues until 6th January 2014, and is definitely worth a visit if you’re in the area.

This summer’s exhibition at the Huntington (running until 28th October) reveals more than 40 intriguing examples of extra-illustrated books from the Library’s collection. Ranging from the late 1700s to the early 1900s, these ‘Grangerised’ volumes (named after James Granger, the eighteenth-century biographer and print collector, and a notable extra-illustrator) expose a fashion for customising printed books with the addition of prints, manuscripts, and other paper materials. One of the stars of the exhibition is a part (containing Romans and 1 Corinthians) of the mid-nineteenth-century Kitto Bible, ‘probably the largest Bible in the world’: originating as a very ordinary two-volume Bible, it now consists of an astonishing sixty individual books. Canonical works appear to have been particular favourites for Grangerisers – impressively expanded editions of Shakespeare and Virgil both feature here, too.

The delicate process of extra-illustration involved taking a book apart at the binding, cutting frames within its pages, pasting additional sheets into these frames, and then re-binding the sheets, which helped to reduce the problem of the volume becoming too awkwardly voluminous. The exhibition’s curators have even made a short film demonstration (http://vimeo.com/65673921) – although they reassure viewers that no eighteenth-century prints were harmed in the experiment. This sense of apprehension towards extra-illustration and the cutting and altering it involved comes across very strongly in the exhibition commentaries, which is not surprising, coming as they do from a curator of rare books. The Huntington has more than a thousand extra-illustrated books in its holdings, and while they are often incredibly striking to the casual viewer, they present all kinds of bibliographical and curatorial tangles for those who look after them. How do you catalogue a book that contains material from many different sources, none of which is necessarily contemporaneous with the original printed volume? How do you catalogue an engraving that would normally be found in an art collection, but which has been pasted into a book with lots of other prints, each from a different source? These ‘illuminated palaces’ have a complicated reception history (they were not short of critics in their heyday), and they continue to challenge our definition of ‘the book’ today.

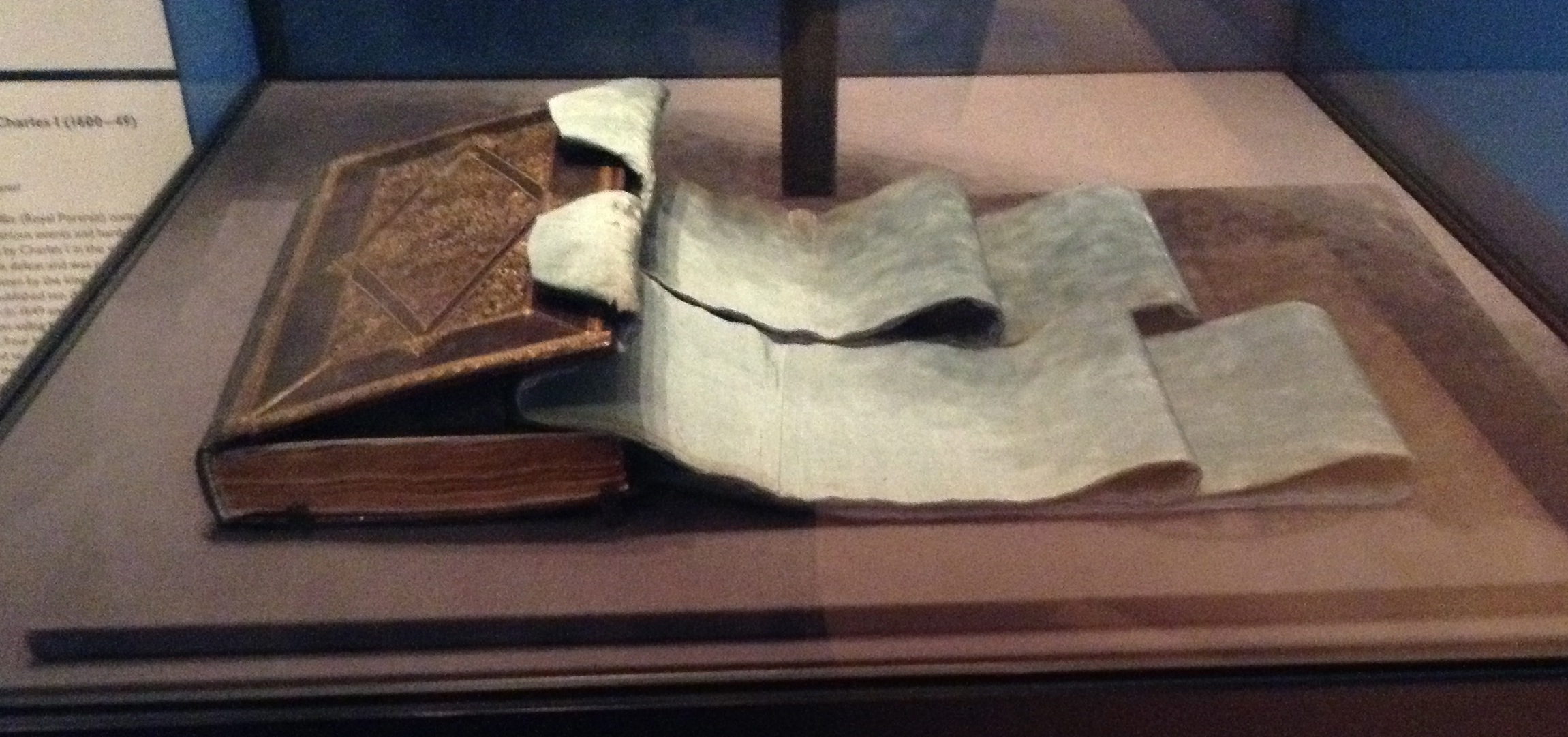

There are lots of wonderful things to see in the latest exhibition from the Royal Collection, In Fine Style, which explores English courtly fashions in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Alongside the sumptuous portraits, suits of armour, and embroidered doublets sits this volume, a copy of the Eikon Basilike with blue silk ribbons attached to its binding:

An inscription inside the book claims that this is the ribbon with which Charles wore his Order of the Garter medal. The Eikon Basilike was one of the most popular seventeenth-century printed works, published very soon after Charles’s death in January 1649 (the Royal Library alone holds around 70 copies). Its content encouraged the belief that Charles was a martyr, and its popularity was matched by a proliferation of relics associated with the executed king. Copies of the Eikon Basilike could often acquire relic status themselves, reportedly being bound with cloth dyed in the king’s blood, or in covers made from his hair. This unique object straddles the categories of book and relic, and you can see more photographs and read about its history in a Royal Collection essay about its conservation, found here on the exhibition website.

In Fine Style continues at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, until 6th October 2013.