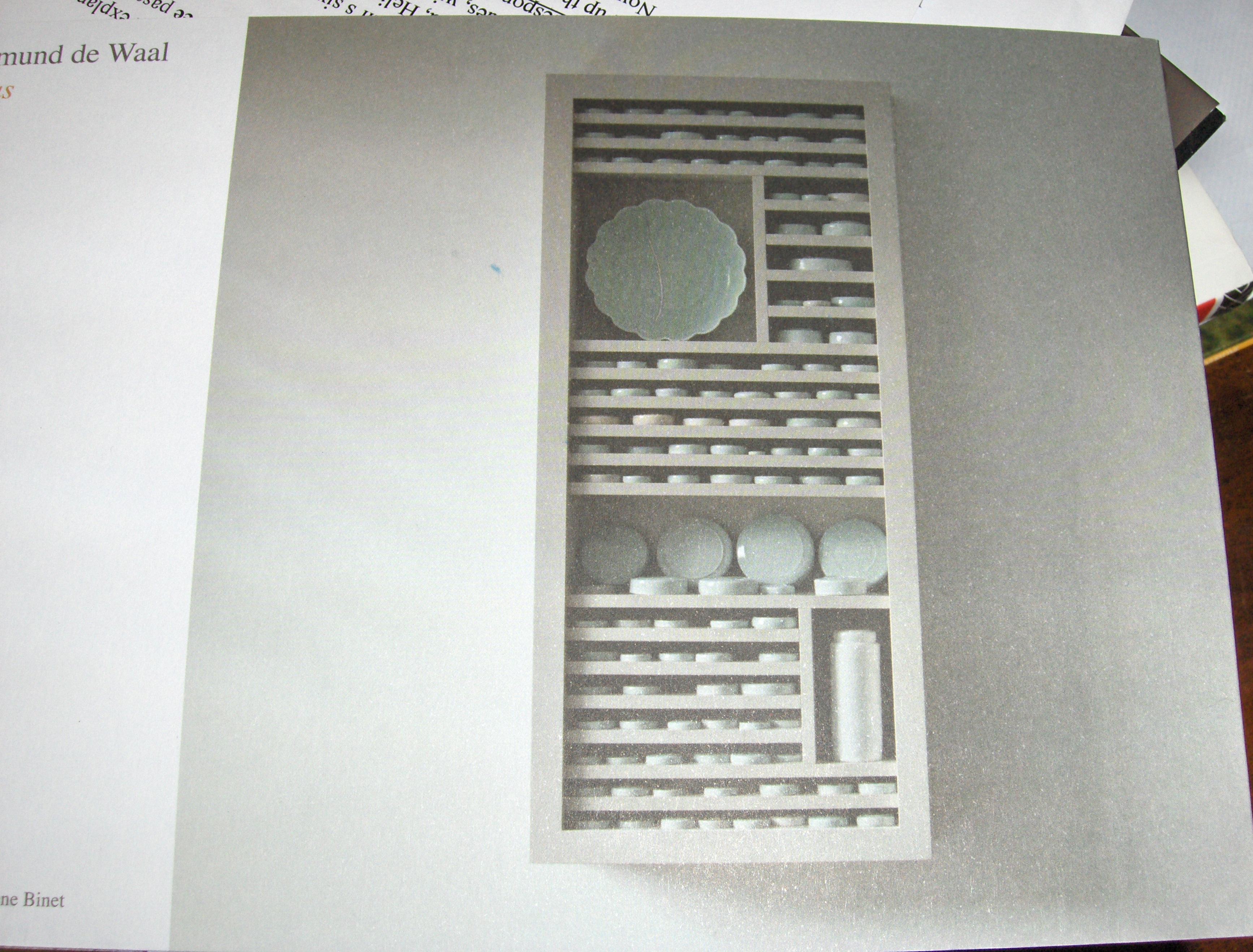

If you have been to the new Alison Richard Building on the Sidgwick Site in Cambridge, you will probably have seen the three vitrines filled with porcelain by the potter Edmund de Waal, which are sunk below the paving just outside the entrance. Inside the building, there is another piece by de Waal: atlas, a wall-mounted vitrine divided into multiple shelves, on which are 120 lids from vessels he has made and broken because they were ‘not quite right’. Yesterday, I picked up a beautifully produced leaflet about these works, in which de Waal writes movingly about his motivations. Of the wall-mounted vitrine (pictured above, in the leaflet), which works so well in the space it occupies, he says:

‘If the structure of the vitrine looks familiar, it is because it is a gentle echo of a manuscript page with texts, footnotes and commentaries in intimate conjunction.’

De Waal intended this and the other vitrines, he reveals, as ‘a kind of archive’, designed for a ‘site full of libraries and archives, and the people who care about libraries and archives’. Located at the threshold to the building, as well as at the heart of the building’s airy atrium, de Waal’s elegant vitrines remind us that our engagement with the materiality of pages, archives, and libraries, while often frustrating and challenging, can also be intensely beautiful.