Wrongdoing in Spain 1800-1936

Read all about it! Wrongdoing is in the eyes of the beholder?

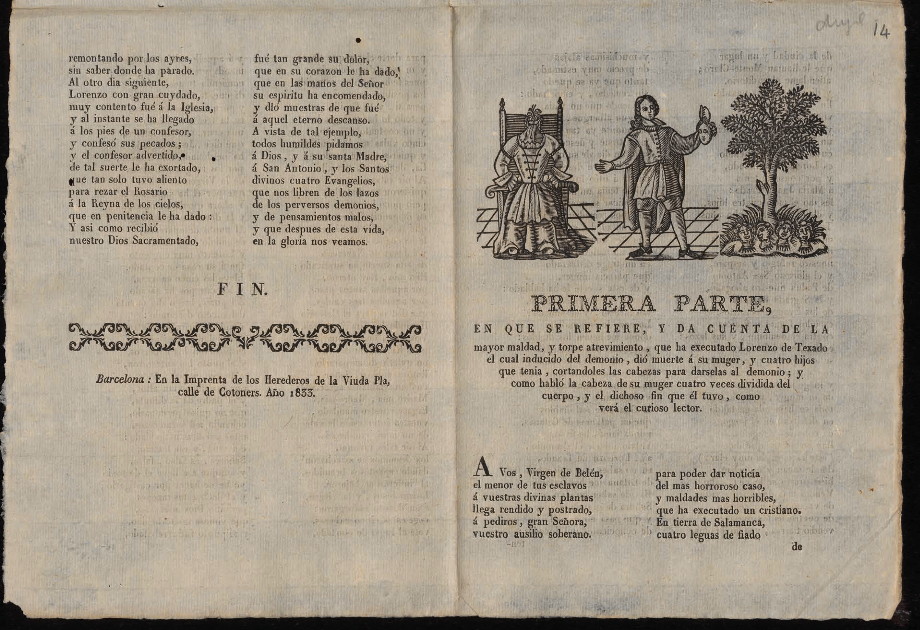

Not quite by accident, but largely because of an interest in ephemeral literature printed in Spain shown by Hispanists here in the early twentieth century, Cambridge University Library has an impressive and rich collection of what a French colleague has termed ‘no-books’. Usually referred to in English as chap-books, and in Spanish as sueltos, or pliegos sueltos (loose leaves or folded loose leaves), these predecessors of the yellow press provide a fascinating bird’s eye view of popular culture from the 18th century onwards. They show us, among other things, versions of how forms of wrongdoing (of different kinds, and of different degrees of severity) were perceived, or were presented to the populace as constructed forms of wrongdoing.

The AHRC-funded project ‘Wrongdoing in Spain 1800-1936: Realities, Representations, Reactions’ is now into its first year. The project is broad in scope, and the research of the PI, the Research Associate and the PhD student will focus on particular aspects of the cultural representation of wrongdoing and its relation (or lack of it) to historical realities at the time of production. The work of digitising the sueltos has a bearing on this, as they represent an important tranche of popular literature, and hence of the popular cultural representation of wrongdoing. The UL has a collection of nearly 2000 sueltos, including nearly 200 poster-sized aleluyas, which typically have 48 illustrations and accompanying text in couplets. The digitisation of this material began in May, and will be followed shortly by a similar digitisation project at the British Library. Eventually between the two collections we will have digitised close to 4500 items. Both here and at the BL, these collections have suffered in the past from a lack of attention from cataloguers, so that at present it is difficult for the researcher to scan the material for themes or characteristics. The consequences of digitising and cataloguing will open the way for a new wave of activity in relation to this material. Not only will digitisation of the sueltos be a significant contribution to the stewardship, conservation and enhanced accessibility of a body of cultural material (under an open license, it will be possible to see and use these fascinating items from all over the world, at any point where internet access is possible), but they will also be catalogued in a way that will make it much easier to work with these sources. An innovation is that the project will do this cataloguing not only for UL items, but for those of the BL also. Held in the Cambridge Digital Library, they will be available through a dedicated website, but also through the general catalogues of both libraries, making the material doubly available.

The AHRC-funded project ‘Wrongdoing in Spain 1800-1936: Realities, Representations, Reactions’ is now into its first year. The project is broad in scope, and the research of the PI, the Research Associate and the PhD student will focus on particular aspects of the cultural representation of wrongdoing and its relation (or lack of it) to historical realities at the time of production. The work of digitising the sueltos has a bearing on this, as they represent an important tranche of popular literature, and hence of the popular cultural representation of wrongdoing. The UL has a collection of nearly 2000 sueltos, including nearly 200 poster-sized aleluyas, which typically have 48 illustrations and accompanying text in couplets. The digitisation of this material began in May, and will be followed shortly by a similar digitisation project at the British Library. Eventually between the two collections we will have digitised close to 4500 items. Both here and at the BL, these collections have suffered in the past from a lack of attention from cataloguers, so that at present it is difficult for the researcher to scan the material for themes or characteristics. The consequences of digitising and cataloguing will open the way for a new wave of activity in relation to this material. Not only will digitisation of the sueltos be a significant contribution to the stewardship, conservation and enhanced accessibility of a body of cultural material (under an open license, it will be possible to see and use these fascinating items from all over the world, at any point where internet access is possible), but they will also be catalogued in a way that will make it much easier to work with these sources. An innovation is that the project will do this cataloguing not only for UL items, but for those of the BL also. Held in the Cambridge Digital Library, they will be available through a dedicated website, but also through the general catalogues of both libraries, making the material doubly available.

The cataloguing itself began shortly after the imaging. A regular rhythm of meetings between Sonia Morcillo, the UL’s expert Hispanic cataloguer, and Professor Alison Sinclair, the PI, has allowed for extensive discussion of how to flag up the subject-matter. More has been learned about the principles of librarianship by the PI than ever anticipated, not to mention being made aware of linguistic gaps through which concepts might fall, and the sheer range of wrongdoing and other related activity that the material covers. The vocabulary of wrongdoing in the two languages is a minefield. First of all, there is no word as such in Spanish for ‘wrongdoing’ (you can have crime, you can have sin, you can have transgression, but nothing like the collective implication of ‘wrongdoing’). The word ‘crimen’ itself usually refers to murder, or at least to violent crime (graphically referred to as a ‘delito de sangre’, or ‘crime of blood’). There are two distinct words for prison. There is no word for ‘elopement’ as such in Spanish, only ‘fuga’, which refers to general flight. And so the list goes on. A further complication is the preference of cataloguers for distinguishing between ‘fiction’ and ‘non-fiction’. In the case of this type of crime-writing, the distinction is far from clear, as popular accounts in sueltos, as in their close cousin, gutter-journalism, amply demonstrate.

The cataloguing itself began shortly after the imaging. A regular rhythm of meetings between Sonia Morcillo, the UL’s expert Hispanic cataloguer, and Professor Alison Sinclair, the PI, has allowed for extensive discussion of how to flag up the subject-matter. More has been learned about the principles of librarianship by the PI than ever anticipated, not to mention being made aware of linguistic gaps through which concepts might fall, and the sheer range of wrongdoing and other related activity that the material covers. The vocabulary of wrongdoing in the two languages is a minefield. First of all, there is no word as such in Spanish for ‘wrongdoing’ (you can have crime, you can have sin, you can have transgression, but nothing like the collective implication of ‘wrongdoing’). The word ‘crimen’ itself usually refers to murder, or at least to violent crime (graphically referred to as a ‘delito de sangre’, or ‘crime of blood’). There are two distinct words for prison. There is no word for ‘elopement’ as such in Spanish, only ‘fuga’, which refers to general flight. And so the list goes on. A further complication is the preference of cataloguers for distinguishing between ‘fiction’ and ‘non-fiction’. In the case of this type of crime-writing, the distinction is far from clear, as popular accounts in sueltos, as in their close cousin, gutter-journalism, amply demonstrate.

The material in itself is fascinating, whether in the portrayal of one killer whose weapon seemed to be a giant pair of scissors, or in the disturbingly recurrent motif of infants being chopped up, fried and offered to unsuspecting adults (shades here of Titus Andronicus….). This last alerts us to a further element: the resonances with classical culture that can be surprisingly present in this most popular of forms.

For further information about this project, please visit Professor Sinclair’s web page at http://www.mml.cam.ac.uk/spanish/staff/as49/