Recently, I have been taking a closer look at a manuscript I consulted this summer in the Folger Shakespeare Library. The volume (MS V.b.132) contains a long and absorbing set of letters by Francis Bacon, carefully copied in the late 1620s or early 1630s by the scribe Ralph (Raph) Crane (Beal BcF 187). When examining the manuscript’s binding and construction, however, my research took an unexpected detour away from Bacon and Crane, and into the everyday world of early modern shipping.

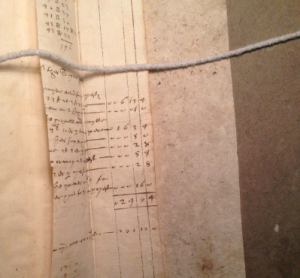

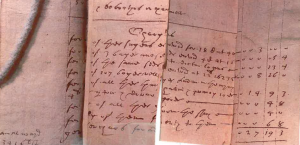

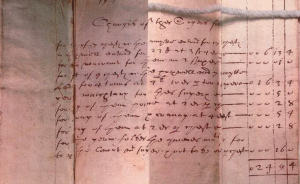

The manuscript’s binding guards are made up of a set of written accounts, covering the recto and verso of a single folio page (pictured). Having photographed the eight exposed page fragments, I reassembled the snippets into two misshapen, but potentially readable, pages (below), to try to date the material. Although the accounts don’t contain any dates themselves, they contain enough references to ships and people to point to a likely time of writing. The pages record the expenses involved in the importation and sale of ‘ambergres’, ‘chests of suger’, and ‘bages’ of ‘anesede’. It is possible to make out the names of two ships – the Hopewell and the Amity – and of some customers or merchants: one ‘collins’, ‘doctor lopus’, and ‘folkes the queenes ma[jes]ti[e’s] […]’.

The manuscript’s binding guards are made up of a set of written accounts, covering the recto and verso of a single folio page (pictured). Having photographed the eight exposed page fragments, I reassembled the snippets into two misshapen, but potentially readable, pages (below), to try to date the material. Although the accounts don’t contain any dates themselves, they contain enough references to ships and people to point to a likely time of writing. The pages record the expenses involved in the importation and sale of ‘ambergres’, ‘chests of suger’, and ‘bages’ of ‘anesede’. It is possible to make out the names of two ships – the Hopewell and the Amity – and of some customers or merchants: one ‘collins’, ‘doctor lopus’, and ‘folkes the queenes ma[jes]ti[e’s] […]’.

From scanning the tables of Elizabethan ships in Kenneth Andrews’ Elizabethan Privateering (1964), and the detailed chronologies of sugar importation in T.S. Willan’s Studies in Elizabethan Foreign Trade (1959), it seems likely that the Hopewell was the ship of that name captained by Abraham Cocke and then William Craston, which carried sugar, ginger, cochineal, pepper and sarsaparilla, and that the Amity may have been the Amity which was employed in the Barbary trade between 1574 and 1594, managed by a syndicate from the Grocers Company. The reference to ‘collins’, to which the account-writer sold ambergris could therefore have been Edward Collins, factor to the brother of John Symcot, who was himself engaged in the sugar trade and also imported on the Amity during 1587-8.

From scanning the tables of Elizabethan ships in Kenneth Andrews’ Elizabethan Privateering (1964), and the detailed chronologies of sugar importation in T.S. Willan’s Studies in Elizabethan Foreign Trade (1959), it seems likely that the Hopewell was the ship of that name captained by Abraham Cocke and then William Craston, which carried sugar, ginger, cochineal, pepper and sarsaparilla, and that the Amity may have been the Amity which was employed in the Barbary trade between 1574 and 1594, managed by a syndicate from the Grocers Company. The reference to ‘collins’, to which the account-writer sold ambergris could therefore have been Edward Collins, factor to the brother of John Symcot, who was himself engaged in the sugar trade and also imported on the Amity during 1587-8.

The accounts also have a celebrity connection: ‘doctor lopus’ is almost certainly the Queen’s notorious physician Roderigo Lopez, who was involved in the importation of aniseed and sumac from 1584 until he was executed in 1594. Lastly, the word ‘grocer’ is likely to complete the line on ‘folkes’: the Royal Grocer Richard Foulkes charged a fixed importation fee on sugar under the royal right of purveyance. This fee was implemented in 1584, and lasted until the abolishment of Foulkes’ post in 1589.

The accounts also have a celebrity connection: ‘doctor lopus’ is almost certainly the Queen’s notorious physician Roderigo Lopez, who was involved in the importation of aniseed and sumac from 1584 until he was executed in 1594. Lastly, the word ‘grocer’ is likely to complete the line on ‘folkes’: the Royal Grocer Richard Foulkes charged a fixed importation fee on sugar under the royal right of purveyance. This fee was implemented in 1584, and lasted until the abolishment of Foulkes’ post in 1589.

With this in mind, it seems probable that the two pages of accounts were written sometime between 1584 and 1589, by an established trader in sugar, ambergris and aniseed. Unfortunately, the Francis Bacon manuscript bound in these accounts was produced much later, and does not touch on Elizabethan spice importation. Although this digression into merchant shipping led to little more than a footnote in my work on the manuscript, the process of reassembling these accounts and tracing their references was a nice reminder of the potential of binding material, and the unexpected nature of manuscript research.