Ben Jonson’s 1624 masque Neptune’s Triumph for the Return of Albion opens with ‘The Poet, entering on the stage to disperse the argument’. The Spanish Tragedy shows Hieronymo presenting the King with a ‘Copie of the Play’ and an ‘Argument of that they show’ before the performance of Solyman and Perseda. Nowadays we might refer to such synopses or summaries distributed to the audience as ‘programmes’. As they are today, programmes would have been useful during performances for their explanation of the masques’ action and symbolism, and as records or tokens of the performance.

Manuscript summaries of speeches and devices were already being distributed in the late sixteenth century at Elizabethan tilts. Philip Gawdy wrote to his father on 24 November 1587, enclosing ‘ij small books for a token, the one of them was given me that day that they ran at tilt’. Roy Strong draws attention to a Revels account payment ‘for the fair writing of all the devices on the 17 day of November … in two copies for the Queen’.

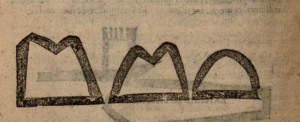

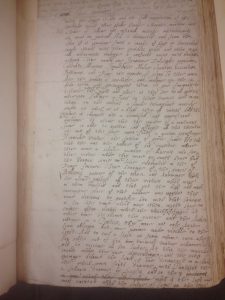

Synopsis of Ben Jonson’s The Masque of Queenes, in BL Harley MS 6947, fol. 143r. By permission of the British Library.

Do any programmes survive from masque performances? Some extant manuscript summaries of masques may have their roots in these elusive books. For example, the summary of Carew’s Coelum Britannicum (1634) now found in BL Harley MS 4931 goes to greater lengths than the printed edition to clarify the masque’s symbolism. It would be easy, however, to confuse these ‘programmes’ with summaries produced for other reasons, such as post-performance accounts, or pre-performance plot proposals for the Court. The summary of Jonson’s Masque of Queenes (1609) now in BL Harley MS 6947, for example, which contains different names for two of the characters, is more likely to have been written for the Court’s inspection before the performance, than copied from a masque programme.

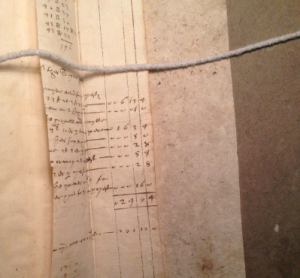

The book which most fits the bill is an undated printed quarto attributed to Aurelian Townshend called The Ante-Masques which, as Karen Britland has recently demonstrated using the evidence of broken type, was printed by Felix Kingston for an entertainment at Oatlands House in August 1635. This quarto summarises the entertainment, including verses from the anti-masques and a ‘Subiect of the Masque’, which explains the masque’s proceedings.

Masques have long been understood as multimedia experiences, incorporating music, gesture, language, stage design and dance. These references to performance programmes reveal that the printed or written page could have also been a part of this experience, and may have been consulted for further information, clarification, or as a record of an ephemeral performance. Unfortunately, these programmes appear to have also lived ephemeral lives themselves.