How do readers comment and read comments on digital texts? In January, the founders of the website Genius announced their intention to ‘annotate the world’, a project which they have described as ‘a wall of history’ and ‘the internet Talmud’. Previously, the site was solely a forum for the collaborative interpretation of rap lyrics, noted for its ‘hyper-intellectualisation of hip-hop’. For example, annotators explain that Jay Z’s line ‘is Pious pious cause God loves pious?’ is a ‘reference to Plato’s Euthyphro dilemma’ which ‘gets at some of the central questions of morality (sovereignty, omnipotence, freedom of will, morality without God)’.

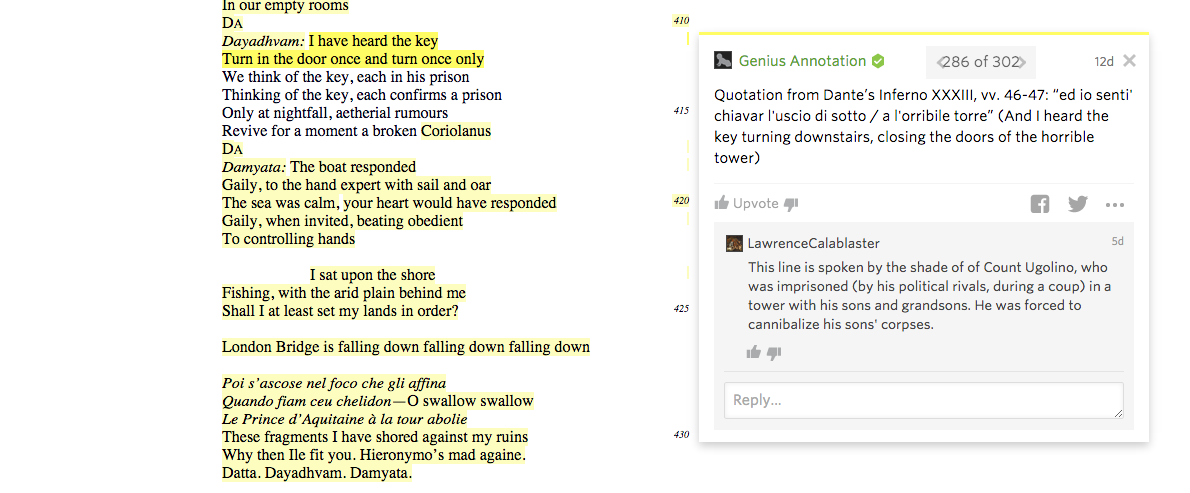

However, the site has recently started to annotate poetry, fiction, historical texts, news stories, legal documents, speeches, drama, podcasts; anything which naturally takes, or can be expressed in, a textual form. The Canterbury Tales, the Magna Carta, Shakespeare’s plays, Wittgenstein’s Propositions, the 2015 Labour Party election manifesto, and many thousands more texts have all received sustained glossing from an expanding community of annotators. Genius.com has now infiltrated the rest of the digital world, and currently allows any webpage on the internet to be annotated. The site explains, ‘whenever you’re confused by or interested in a passage, you can click on it to read an annotation that explains in plain language what you’re reading and why it’s important’.

How can a project like this change our experience of digital reading? Giving readers a means to respond to texts on the web is not new: comment-boxes, and streams of reader comments, have been found at the bottom of webpages for a long time. But the annotation format integrates text and comment within the text space, explaining the text whilst it is being read. If everything is annotatable, what would it mean to encounter blank or unannotated text: a lack of reader interest, an idea too obvious or difficult to be annotated, or a veneration of the text? As texts generate more prose annotations, which can also be commented upon themselves, could digital texts be buried under all this exegesis? And what does this drive to produce and read explanatory text say about our culture of reading? In 1991, Thomas McFarland suggested that textual glossing is part of an attempt to construct connections of meaning in the face of cultural disintegration: ‘footnotes and other annotational apparatus are denials of cultural fragmentation; the greater the actual disintegration of culture, the more in fashion do footnotes become’. Perhaps the internet is where readers encounter texts in their most fragmented and least anchored forms.