Beneath the magnificent barrel-vaulted ceiling of the Playfair Library in Old College, Edinburgh, over two hundred people gathered on a mid-July weekend for the third Material Cultures conference organised by the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for the History of the Book.

A glance through the elegantly produced programme reveals the diversity of the disciplines and backgrounds represented. Over the three days, discussions of (to give an incomplete list) the buying, selling, publishing, giving, sharing, collecting, saving, printing, editing, listing, archiving, translating, illustrating, annotating, dedicating, digitising, indexing, and binding of material texts reached far beyond the traditional scopes of ‘bibliography’ and ‘book history’. Some of the panels focussed on particular people and places; in light of our location there were panels dedicated to the John Murray Archive in the National Library of Scotland, to the history of Shakespeare scholarship in Edinburgh, and to some specific manuscript anthologies in Renaissance Scotland. Other panels used broader themes such as ‘Printers Across Borders’, and ‘The Business of Books’ to bring together material texts usually separated by geographical and chronological distance. The titles of quite a few other panels and the papers within them were mystifyingly vague, and as we were not supplied with abstracts of papers this meant a certain amount of advance guessing was necessary. This in itself was a reminder of the sweeping consequences of ‘material culture’ and the challenges we face in talking meaningfully about texts as ‘material’ in inter- and intra-disciplinary ways.

Indeed, such was the scale and breadth of the conference that it sometimes felt that several conferences were happening simultaneously. Most noticeably, it was certainly possible to fill three days listening to papers about the digital: digital archives, digital texts, digital editions, screen media, virtual museums, digital bindings, Kindles, hypertexts, and e-books all featured, demonstrating the importance of this rapidly developing field of technology, research, and practice. It was equally possible, however, to experience a conference relatively free from the d-word, although in the final plenary session Jerome McGann warned us not to underestimate the ever-increasing complexity of the relationship between scholars, libraries, and digitisation.

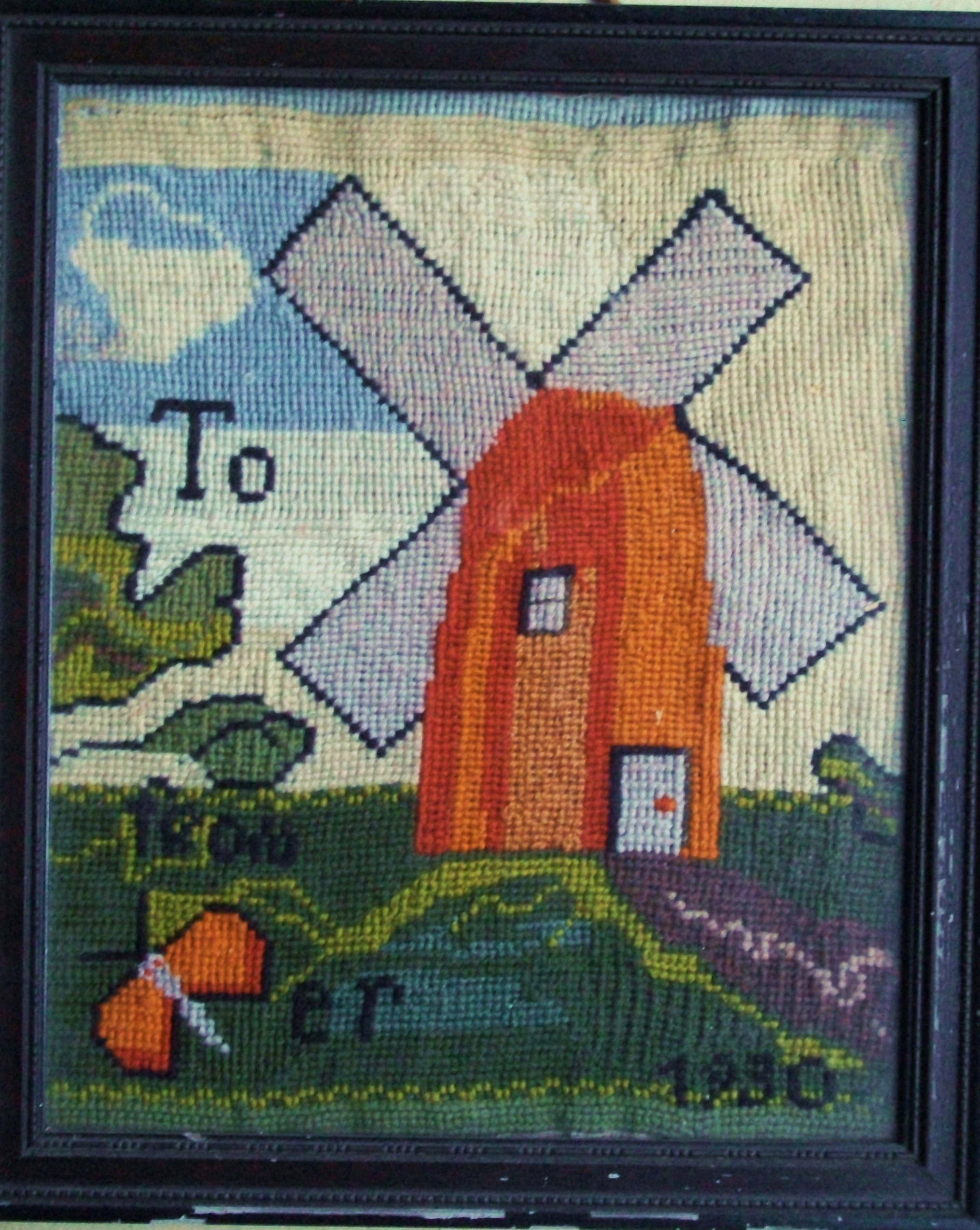

In the opening plenary session, Roger Chartier asked some searching questions about the history of attitudes towards authorial manuscripts, suggesting the need to appreciate the function of the library or archive as the site of preservation not only of material texts, but also of particular sets of historically specific ideas and conventions about authorship. Later that day the second plenary session starred Peter Stallybrass, whose presentation developed some of the ideas he introduced at the inaugural CMT conference earlier this year. Pointing out the limitations of the traditional division we set up between ‘print’ and ‘manuscript’, he urged us to consider print as a medium which incites manuscript: ‘printing for manuscript’. In his lavishly illustrated talk, Stallybrass demonstrated how we can look again at everyday printed ‘blank’ documents which require completion with handwritten details. Immigration landing cards, cheques, birth certificates and field service postcards, for example, were juxtaposed with seventeenth-century funeral tickets. By viewing print as a medium which crucially creates space for manuscript, Stallybrass argued, we might consider afresh the presence of handwriting in early printed books, and think further about how we differentiate between ‘print’ and ‘manuscript’.

Such questions of terminology, definition, and categorization underpinned many of the discussions at this conference. The ‘material text’ crosses many disciplinary boundaries, and as scholars, librarians, and readers, our task is to continue to explore the terms and language with which we may most fruitfully talk about the ‘text’ as something ‘material’.