This week sees the broadcasting on BBC Radio 4 of the second part of ‘A History of the World in 100 Objects’, a collaboration between the BBC and the British Museum. Over the next eight weeks Neil MacGregor, the British Museum’s Director, will cover 1800 years of history from 300 BC to 1500 AD, as he explores another group of objects from the Museum’s collection.

The online presence of the project is key to the accessibility of the objects. There are short videos about some of the objects, and the 100 radio broadcasts can be downloaded as podcasts. The high quality photographs in the online gallery allow close inspection of each object. Furthermore, other institutions and individuals can participate with their own objects. Already over 350 museums across the UK have registered with 100 objects from their collections, and members of the public can also record details of their own objects online.

I have been thinking about the handful of objects from the 100 chosen from the British Museum’s huge collection which present us with ‘text’. The surfaces of some of the objects are decorated with pictorial representations; the illustrations on the mysterious Standard of Ur, for example, give us scenes of war in Mesopotamia over 4000 years ago. Hieroglyphs on an ivory sandal label found in the tomb of the Egyptian King Den (c. 2985 BC) celebrate the wearer’s military conquests. There are wall painting fragments, masks, sculptures, carved reliefs, and statues, all of which present us with anthropomorphic representations. Not so many of the objects actually feature writing, however.

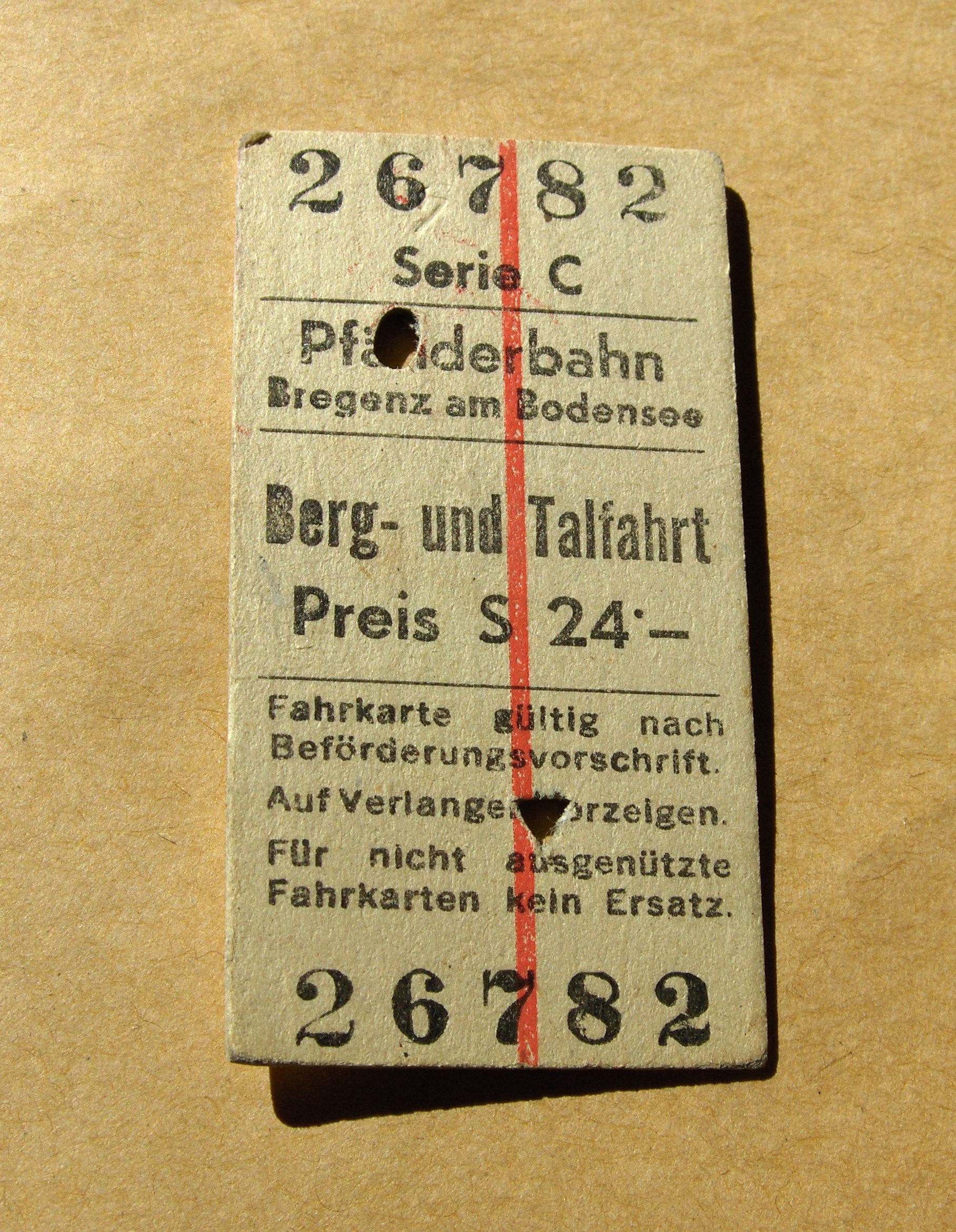

The objects which do display text include a famous cuneiform tablet from Assyria (700-600 BC) telling the story of a great flood, which was sensationally compared with the Biblical flood when it was first translated in 1872; an Indus seal bearing some of the oldest writing from South Asia, as yet undeciphered; an early writing tablet from Mesopotamia; and an Egyptian mathematical papyrus. There is writing which plays with the aesthetic potential of ink on paper, as in the Tughra of Süleyman the Magnificent, and there are mathematical and scientific instruments which combine words and numbers. Text can be found on several maps, on Dürer’s woodcut print of an Indian rhinoceros, and on a broadsheet marking the centenary of the Reformation in Germany. Forms of money emerge as significant textual objects across thousands of years: there are five coins including a coin with the head of Alexander and a penny defaced by Suffragettes, a Ming banknote, and the newest of the 100 objects, a credit card.

In these objects, writing is found on flat surfaces and three-dimensional forms. It is found on the inside and outside of objects. It is carved, engraved, embossed, handwritten, stamped, and printed, and tells us about changing technologies of the word. Many different languages, ages, and civilisations are represented, and the writing on these objects serves many different rhetorical functions too. The 100 British Museum objects, as well as all of the other objects registered on the website, can be sorted and compared by themes, including ‘Food’, ‘Travel’, ‘Protest’, ‘Body’, ‘Clothing’, and ‘War’. I would like to suggest another theme: ‘Text’. What could we learn by comparing all of the objects which feature writing in some form? In each example, how does the writing relate to the object? How do the specific materialities of these objects shape and inform their function as texts? Should we think about these objects differently from the objects without any text?

PS: The 100th object is still a mystery: its identity will be revealed in the Autumn. Any guesses?