In the most recent episode of the BBC’s Call the Midwife (a drama about a community of nursing nuns in the East End in the 1950s, based on the memoirs of Jennifer Worth), we learn that the eccentric Sister Monica Joan, now in her nineties, maintains a small personal library. The amount of time she spends tending to her ‘repository of knowledge’ (including rebinding volumes with leather and paste, and ripping the ‘heretical’ pages of the Apocrypha out of a Bible) is the cause of much frustration for the indomitable Sister Evangelina, who mutters ‘Never been a reader. Always been a doer’. Arranging her books on makeshift shelves, Sister Monica Joan complains that ‘the Dewey Decimal System is altogether too earthbound, and likely to speak loudest to pedantics’ – and instead she puts volumes by Astley Cooper and Rousseau next to each other, so that they can converse, while ‘Plato and Freud can be companions in their ignorance’. All of this playing with books is intended, as is usually the case with Sister Monica Joan’s especially eccentric moments (she is getting dementia) for bittersweet comic effect. However, contrary to Sister Evangelina’s suspicions, ‘reading’ turns out to be ‘doing’, too. In the main storyline, two young brothers are very sick, and the doctor cannot find a diagnosis for their mysterious symptoms. Noone has an answer other than the old-fashioned catch-all of ‘failure to thrive’, until Sister Monica Joan hears about it and runs through the rain in the night to give the doctor a book from ‘the reign of Queen Anne’, from her collection. I’m not sure what this book was, but it leads him to diagnose the two children with cystic fibrosis (in the 1950s, this had only recently been identified as a genetic condition). The elderly nun is vindicated, for she spoke truth in her perceived madness, and as the episode came to a close, it was pleasing to see that she was given a proper bookcase for her precious volumes.

A friend’s Facebook post:

‘Uh oh. I just tried to zoom in on a picture – in a book – using the iPad-fingers-moved-apart-manoeuvre. In my defence, the page was shiny.’

I sympathise: I’ve been looking at some illustrated books this week and reflecting on how rarely you can actually see the detail you need to see in a reproduction of a painting. In this sense, digital technology seems like a distinct advance on print. The downside is that we are going to lose any sense of scale–the relationship between the body and the artefact cannot yet be reproduced, nor does anyone seem to care much about it. But the size of a painting, or of a book for that matter, would in the past have been part of the point of it, framing your whole experience.

So I hope my 3-D printer, when it arrives, will allow me to create a LIFE-SIZE reproduction of the Mona Lisa.

Over Christmas I read Memoirs of a Leavisite by David Ellis, Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Kent. It left me no more of a fan of the great F. R. Leavis than I was when I began, but it made me realise how much his theories of literature might still flow beneath the surface of my own reading and teaching–so I read it both with pleasure and with a kind of fascinated horror.

As befits someone brought up in Leavis’s school, Ellis confesses that he has little feel for or interest in books as material objects, though he admits one exception: the works of Roland Barthes in the Éditions du Seuil:

“As he became more famous he was able to publish shorter texts in this format, with bigger print, so that his book on photography (La Chambre Claire), with its wonderful expanses of white around the large lettering, became my model of what a book should look like, especially at a time when English academic publishers were cramming more and more words onto the enlarged pages, and thinner paper, of their books. With my eyesight weakening, I became a propagandist for this model until someone publishing one of my own books rather irritably told me that she was considering offering it to the public with a free white stick (an addition, I ought to have pointed out, that would not help the poorly sighted to read the print better).”

As well as saying a lot about the unending tussle between writers and publishers, and the hidden visual cues that shape our reading, this is also a good example of Ellis’s richly maudlin prose–perfect reading for a dark December day…

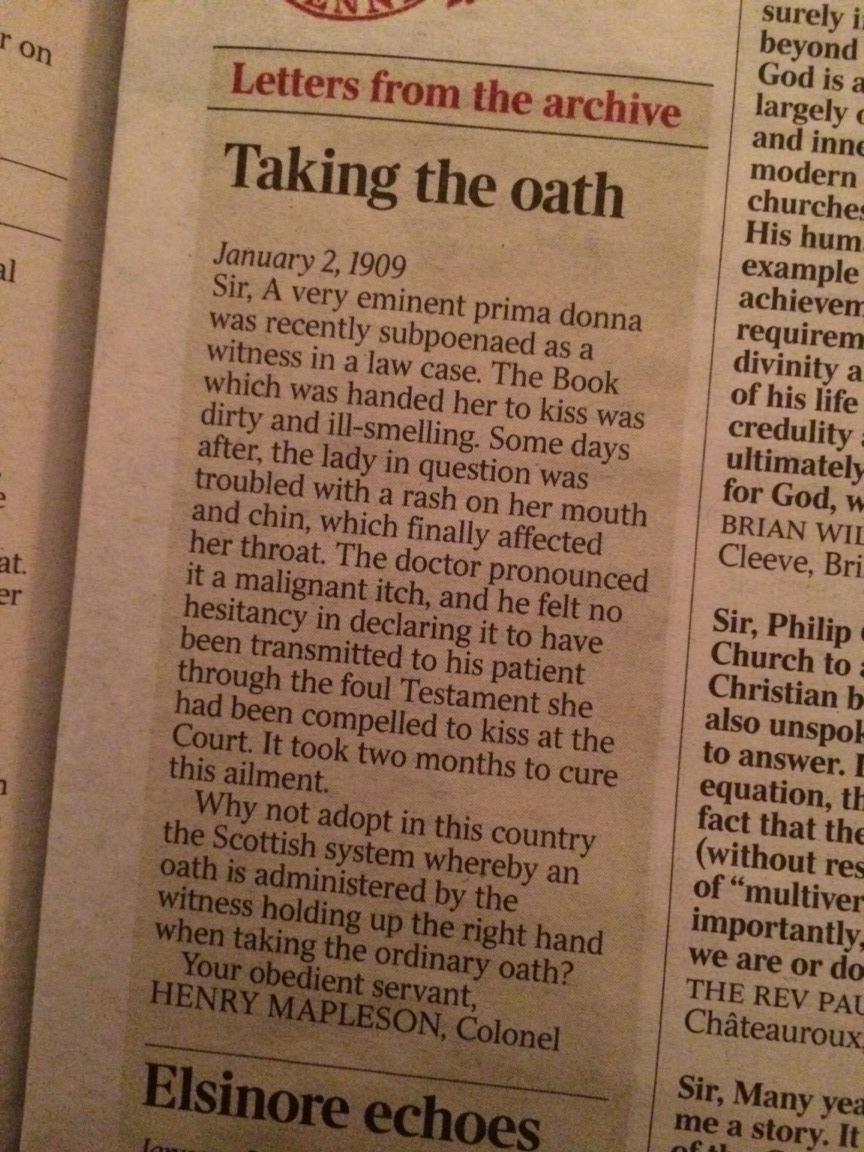

One of the broadsheets found in their archive this sorry story of a witness in a law case and the ‘foul Testament’ from which she contracted a ‘malignant itch’ after kissing it by way of swearing her oath. While a certain ’eminent prima donna’ of our own times has met with other troubles after her recent appearance as a witness in a high-profile trial, she has at least avoided this troublesome complaint. The original correspondent would be pleased to know that kissing the Book is no longer necessary in Court…

One of the broadsheets found in their archive this sorry story of a witness in a law case and the ‘foul Testament’ from which she contracted a ‘malignant itch’ after kissing it by way of swearing her oath. While a certain ’eminent prima donna’ of our own times has met with other troubles after her recent appearance as a witness in a high-profile trial, she has at least avoided this troublesome complaint. The original correspondent would be pleased to know that kissing the Book is no longer necessary in Court…