A post by Lara Harris, PhD student in the Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic

Cambridge, a city brimming with history and with manuscripts, is currently hosting two exhibitions that offer glimpses into the fascinating world of medieval medicine. At the University Library, the Wellcome Trust-funded project ‘Curious Cures’ displays an array of Middle English medical manuscripts (ca. 1200-1500), providing visitors with a holistic overview of medicine in late medieval England, from classical humoral theory to astrology, uroscopy, and surgery, along with numerous charms and magical remedies.

Perhaps medieval astro-physicians would have been able to foresee how the stars would align, such that another exhibition, nestling a short walk away within the English Faculty Library, would be on display at the same time. ‘Garden of Healing’, which I curated, offers an exploration of medieval medical manuscripts from almost exactly the same period (ca. 1290-1550). The main differences are that mine is focused on medieval Scandinavia, and that it solely addresses gynaecological texts.

I had the opportunity of handling, transcribing and translating a few of the manuscripts on display in ‘Curious Cures’ in a week-long summer workshop in 2023. Even back then, I was struck by the similarities between the remedies I had seen in my Scandinavian codices and those in the Middle English ones. I had not been able to trace many of these medical recipes, but the fact that they (or at least, versions of them) existed meant that I was not simply dealing with local Scandinavian knowledge, but rather a much more complex picture, where channels of communication were hazy but undeniable.

Visiting the ‘Curious Cures’ exhibition gave me the opportunity to deepen my understanding of my own medieval medical project by placing my Scandinavian remedies in a wider European context. Simultaneously, accessing the much larger Middle English corpus introduced me to an array of remedies that I had never come across in the Scandinavian material– such as a treatment for pregnancy cravings, an ailment absent in all extant Scandinavian manuscripts. But what makes this kind of research so exciting is that there are elements from the Scandinavian framework that can also clarify and put into context some of the Middle English medical texts.

Phantom Women

I was very pleased to see that ‘Curious Cures’ had dedicated a corner of the exhibition to the recognition of women in medicine as well as of texts addressed to the female body. The exhibit label explains that there are very few records that serve as evidence for women’s involvement in the practice of medicine, and that very few women owned medical books. The text goes on to explain that female medical authors are very rare, as women were banned from accessing university education, and instead they learned on the job. This is also the case in the Scandinavian realm. Out of the 36 extant medical manuscripts hailing from Scandinavia (clearly, a much thinner corpus), none can definitively be attributed to women. However, nine of them are (in)directly connected to women; and photographs from seven of these are displayed in my exhibition at the English Faculty.

Noblewomen

Two of the Scandinavian manuscripts from the turn of the sixteenth century—X 23 4to (Royal Library of Sweden) and Saml. 1a 4to (also known as Codex Grensholmensis, Linköping City Library) — belonged to Swedish noblewomen: Christina Månsdotter of the noble house Natt och Dag, and Maetta Ryningsdotter of Grensholm Castle, respectively. Both of their names are written down in the manuscripts, and in the case of Maetta, her birth date and place are added too, along with those of her children – and their star signs! It is probable that Christina’s manuscript was written specially for her, whereas Mætta’s was purchased by her family and then expanded at Grensholm. Both cases point to the fact that women (at least those of a certain status) studied and likely practiced medicine. In Mætta’s case, her interest may have been directed towards healing her immediate family and caring for her children. As for Christina, too little is known of her life to ascertain whether her pursuit of medical knowledge was simply a personal calling or whether she acted as a local or family healer.

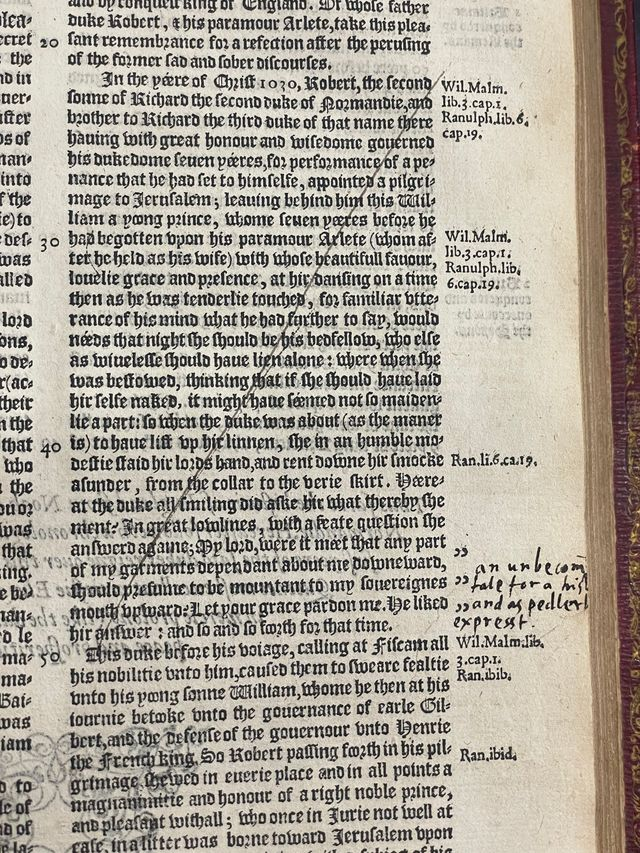

Royal Library of Sweden X 23 4to, p. 223, an image from the famous Danske Urtebog (‘Danish Herbal’), naming Ligustrum as a remedy for menstruation, which is called orenlik thing nidhan (‘unclean thing down below’).

The Bridgettines

Three of the manuscripts on display hail from different Bridgettine institutions across Scandinavia. The Bridgettine Order, established by St Bridget of Sweden (1303-73), was unique in that, while they were run by an abbess, its cloisters housed both monks and nuns. With royal backing and funding, each abbey was wealthy and powerful, possessing infirmaries, botanical gardens, and scriptoria.

It has generally been believed that, although the manuscripts in these cloisters were written by the monks, many were written for and/or used by the nuns; and given the long sections on gynaecology and obstetrics, it is likely that women used those manuscripts to treat themselves and pilgrims seeking medical care.

Women Authorities

The most striking example sits inside the last case of the exhibition. It consists of an unassuming manuscript with no shelfmark entitled Huskurer och Signerier på Danska (“House Cures and Charms in Danish”), dating from the second quarter of the sixteenth century. This manuscript is slightly younger than those in the ‘Curious Cures’ exhibition, which ends in 1500. However, it still falls within what is considered the Scandinavian Late Middle Ages, which is often extended to around 1550. This manuscript offers the only piece of medical text that ascribes two remedies for cancer to two distinct women: an old woman based in Halland (modern-day Sweden), and another with breast cancer in Augsburg, Germany.

Concluding Thoughts

The ‘Curious Cures’ exhibition at the University Library offers a comprehensive glimpse into late medieval English medical practices. My ‘Garden of Healing’, smaller in scale (and displaying reproductions rather than original manuscripts) focuses specifically on remedies for gynaecology and the question of female healers in medieval Scandinavia. Together, these exhibitions contribute to a deeper understanding of medieval medicine and show that women played an active part in healthcare, even if they undertook their duties in silence.

An image from Upps D 600, with a crossed-out albeit still legible passage on contraception.