Back in 2019, I used this blog to raise the possibility that a copy of the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, held in the Free Library of Philadelphia, might bear annotations in the hand of the poet John Milton. The tantalising notes, often taking the form of tiny textual corrections and scratchy brackets in the margins, had just been analysed in detail for the first time by a scholar at Penn State, Claire M. L. Bourne, and her dating and description made it look as if a Miltonic provenance was a distinct possibility. Thanks to digital technology and in particular social media, you can now get instant responses to even the wildest propositions, and within a few hours I made contact with Claire and floated the idea with the wider academic community. I received rapid confirmation that this was more than just a viable idea–it was actually true. Claire and I spent the Covid lockdown giving online talks about the volume, and last year we published an article describing it in detail, in the journal Milton Quarterly.

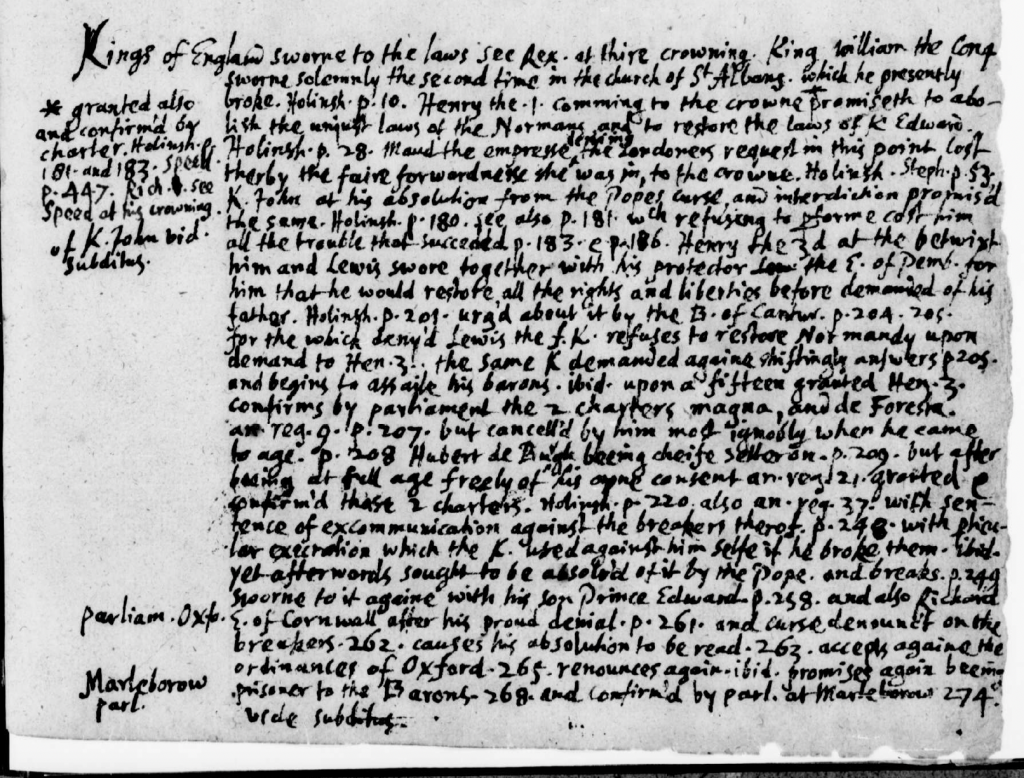

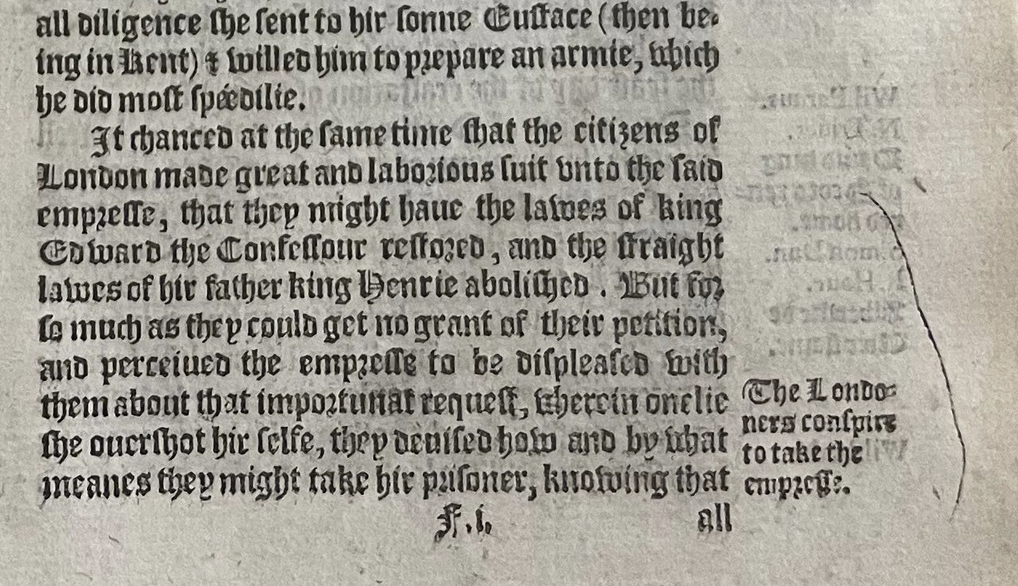

Fast forward to 2024 and another book from Milton’s library has resurfaced, which I’ve not yet had time to discuss here. At the end of March, scholars from Arizona State University hosted a Research Forum at the public library in Phoenix, with the aim of exploring a collection of books bequeathed to the library in 1958 by Alfred Knight, a real estate magnate and philanthropist. Among Knight’s books was a copy of Holinshed’s Chronicles (1587), a gargantuan work that charted the histories of England, Scotland and Ireland from their mythical origins through to the present day. And among the scholars present were Aaron T. Pratt (curator at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin), and the aforementioned Claire M. L. Bourne. Aaron spotted some marginalia that roused his suspicions; Claire took a look and confirmed those suspicions; and then Claire sent me some images to see if I agreed. The identification was relatively easy for us to authenticate, not just because of the handwriting, but also because Milton took detailed notes from his reading of Holinshed in his Commonplace Book (Add. MS 36354), now in the British Library. It was immediately clear that there were strong connections between the marks in the book and the notes. Here, for example, is an excerpt from the Commonplace Book, in which Milton collects evidence that kings of England (unlike American Presidents?) are not above the law. A few lines down he reports that the Empress Maud, failing to revoke the laws of the Norman invaders, lost the support of Londoners and with it her claim to the crown. And beneath that is the section of Holinshed from which he gleans this information, marked with a marginal bracket.

The match is by no means 1:1, but there are so many cases where the Holinshed ties up with the Commonplace Book evidence in this way that there can be no doubt that the annotator is Milton.

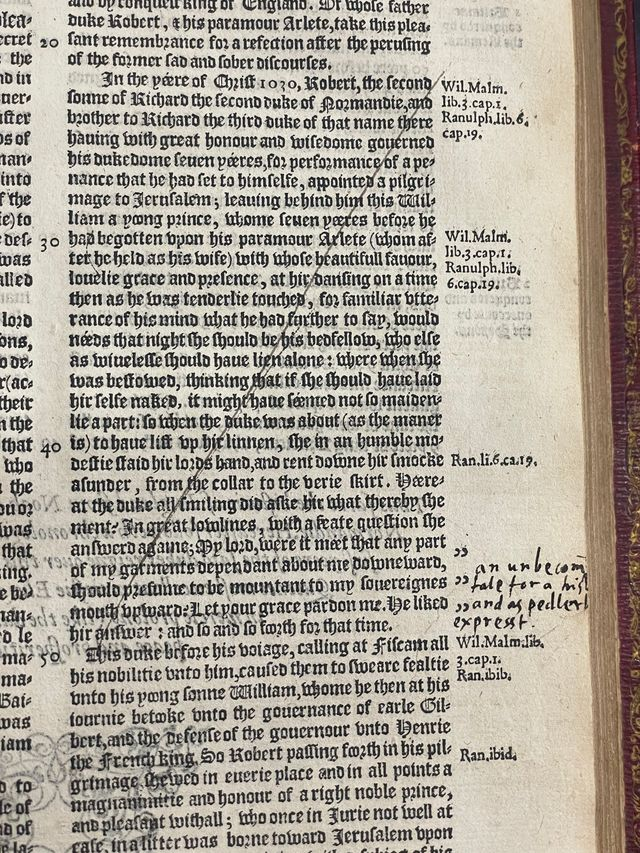

That said, there are so many annotations in this enormous book that it is going to take some time for us to process them and to work out they have to tell us about Milton’s reading practices. We published a preliminary account in the Times Literary Supplement in May; in that piece, the star exhibit was a photograph which shows Milton censoring his Holinshed by running a line across a passage which described how Arlete/Herleva, the mother of William the Conqueror, behaved when she was summoned to the bed of the Duke of Normandy. In the margins, he added a critical note: ‘An unbecoming tale for a history and as pedlerly expresst’ (or something like that–his words were cropped when the book was rebound). ‘John Milton was a prude‘ was how the story was covered in the online Daily Mail, offering news that may not have come as a huge shock to readers of Comus and Paradise Lost. Other images that we used in the article showed Milton citing other texts he had read, including Edmund Spenser’s View of the State of Ireland and ‘the booke of Provenzall poets’, i.e. Jean de Nostredame’s Les vies des plus célèbres et anciens poètes provençaux (1575), a book that was not previously known to be on his shelves.

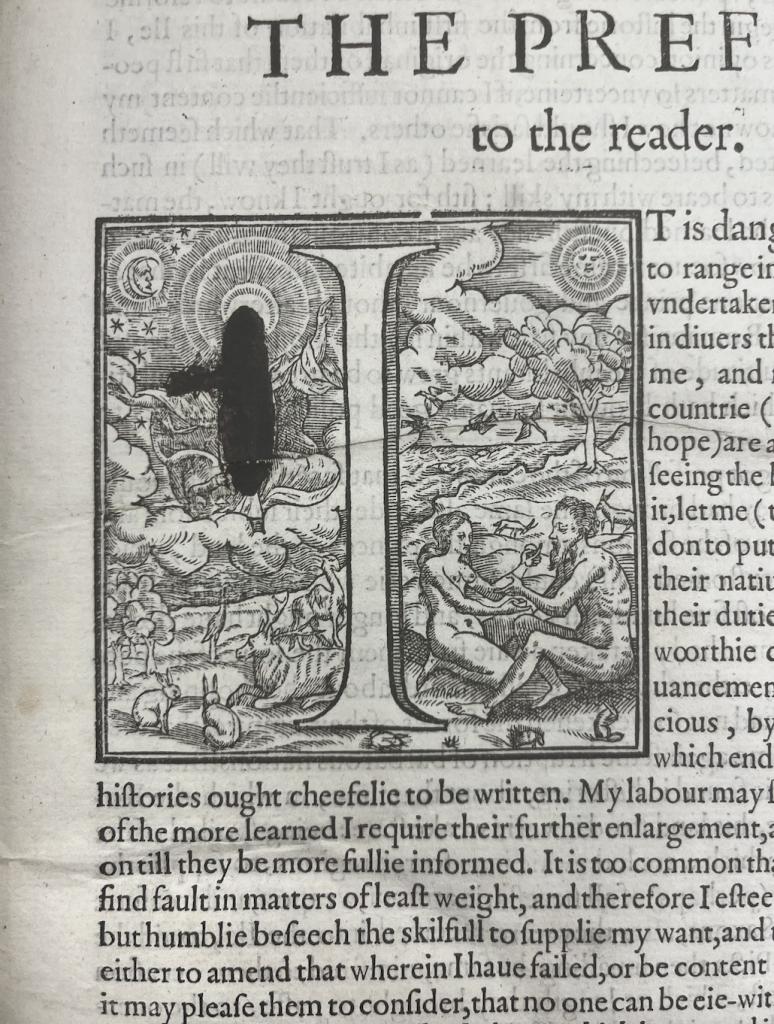

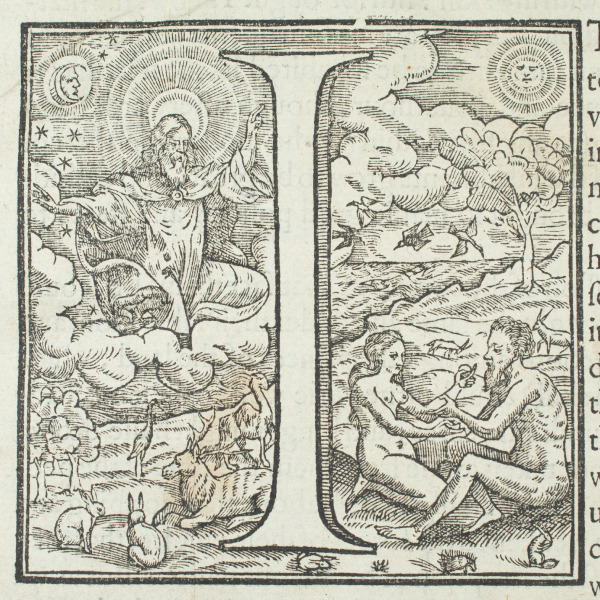

We thought we had found the juiciest images to illustrate our article, but we missed one that might just turn out to be the juiciest of all. This is the woodcut initial ‘I’ that kicks off the Preface to the second bound volume of the Chronicles. As you can see, it depicts Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, with the newly-created world all around them. But what is being covered up by that big black mark up in the sky to the left?

The answer is, of course, that it is God, as you can see by contrasting this version of the same letter, from a copy of the 1587 Chronicles at the Harry Ransom:

So what exactly is that black splodge doing, covering up God? The answer is, almost certainly, that this is another act of censorship. Protestants objected to the visual depiction of God, viewing it as an incitement to idolatry, and from the early sixteenth century (in a process documented by the historian Margaret Aston), pictorial representations were frequently replaced with the tetragrammaton, the four Hebrew letters for the God of Israel: YHWH. Holinshed’s image offended against a widespread prohibition; hence its vigorous correction in this copy.

The next question is: so who did the correcting, and was it Milton? In a recent article entitled ‘Milton among the Iconoclasts’ (in Depledge et al., eds, Making Milton: Print, Authorship, Afterlives [2021]), Antoinina Bevan Zlatar surveys the poet’s lifelong engagement with iconoclasm (at its most conspicuous in his prose work attacking the veneration of the executed Charles I, Eikonoklastes), but suggests that Milton did not adopt the extreme puritan position on the depiction of the deity. In Paradise Lost, Milton permits his God to have the kind of human features that he given in Scripture; this is a God who can be said to sit on a throne, and to have an eye that he can bend down to view his works. That said, Zlatar also reminds us that Milton casts God the Father as invisible, ‘throned inaccessible’ in a blaze of glory, and presents the Son as the visible form of the Father. So perhaps he did have difficulties with too defined and delimited an image of God, as ‘an old man sitting in heaven on a throne with a sceptre in his hand’ (to quote the contemptuous description of the puritan William Perkins). Determining the date and the origins of that smudge of black ink in the Holinshed will be tricky, perhaps requiring non-invasive pigment analysis. At this stage we can only say: it could be Milton.