Earlier this month I heard a seminar paper about centaurs, which ranged across the history of thinking about these hybrid horse-people from ancient Athens to sixteenth-century England. Along the way the speaker, Micha Lazarus, referred to Lucretius, who dismissed the possibility of centaurs on the grounds that the life-cycles of horse and human were so different (‘a horse reaches its vigorous prime in about three years, a boy far from it’).

The discussion reminded me of a twelve-line poem by William Empson called ‘Invitation to Juno’, which begins:

Lucretius could not credit centaurs;

Such bicycle he deemed asynchronous.

‘Man superannuates the horse;

Horse pulses will not gear with ours.’

These lines, first published in 1928 when Empson was a student in Cambridge, refer to the myth of Ixion, a mortal king who attempted to have an affair with Juno, wife of Jupiter, but was foiled by her husband who sent a cloud in place of his wife. Ixion’s union with the cloud led to the creation of the race of centaurs, whose nature conjoins two cycles–‘such bicycle’, as Empson puts it. (As punishment for trying to father a demigod, a ‘two-wheeler’, Jupiter fastened Ixion to a single burning wheel).

Like many of Empson’s poems, ‘Invitation to Juno’ reads like a cryptic crossword. It’s bizarrely compressed and requires elaborate decoding. The poem alludes not just to Lucretius, but also to Darwin, Dr Johnson, and the growth of embryonic heart tissue; it’s not surprising that it requires three and a half pages of notes in the latest scholarly edition by John Haffenden. But were Empson’s sources all abstrusely learned? Yesterday I nearly fell off my own bike when I passed this ‘ghost sign‘ on King St in Cambridge.

It turns out that a company called Centaur Cycles, based in Coventry, made bikes from 1876 to 1915 (they were taken over by Humber in 1910, and production moved to Stoke). There are some lovely examples of their advertisements here; the testimonials report that a Centaur is ‘a wonderful machine’ which ‘mounts hills splendidly’–‘a great luxury after a cheap and nasty mount’. Empson was later known for devotion to a clapped-out bike; a student at Sheffield in the 1950s recalls his riding a ‘very old, preposterously rusty sit-up-and-beg bicycle, wobbling stoically amid the smog and tramlines of Western Bank’. Was it, I wonder, the last of the Centaurs, asynchronous as ever? Or did Empson just see this sign (or signs like it), and start thinking about the intricate relationship between man and mount, ravelling up the tangle of allusions in the poem?

as the neutral holder and transmitter of its materials–could be busted once and for all. This might mean finding ways in which archivists, librarians and curators could be fully credited for their intellectual contributions, so that they would cease to be viewed merely gatekeepers and custodians of the past. There are formidable obstacles to this, mainly to do with the funding pressures that dog the majority of collections. But the conversation seemed to offer a glimpse into a brighter future.

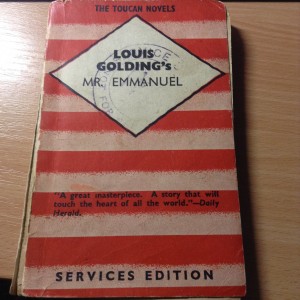

as the neutral holder and transmitter of its materials–could be busted once and for all. This might mean finding ways in which archivists, librarians and curators could be fully credited for their intellectual contributions, so that they would cease to be viewed merely gatekeepers and custodians of the past. There are formidable obstacles to this, mainly to do with the funding pressures that dog the majority of collections. But the conversation seemed to offer a glimpse into a brighter future. So we’re invited to imagine Venetian bookbuyers weighing the cost of a Bible against the cost of six chickens or five geese; to witness the future Queen Katherine Parr giving her uncle a prayer book, and asking him to remember his ‘louuynge nys’ when he looks on it; to admire a doctor’s drawing of a foetus in the womb in the margins of a medical book. A student at the University of Padua spills ink on his Livy, and writes fastidiously around it, in Latin: This blot … I stupidly made on the first of December 1482′. The books are often marvels in themselves, but they really come to life in the hands of their owners.

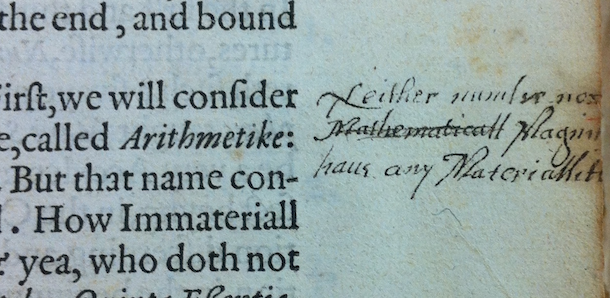

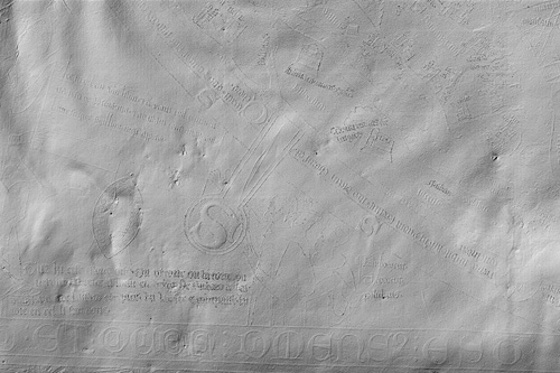

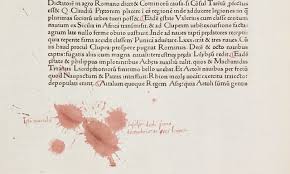

So we’re invited to imagine Venetian bookbuyers weighing the cost of a Bible against the cost of six chickens or five geese; to witness the future Queen Katherine Parr giving her uncle a prayer book, and asking him to remember his ‘louuynge nys’ when he looks on it; to admire a doctor’s drawing of a foetus in the womb in the margins of a medical book. A student at the University of Padua spills ink on his Livy, and writes fastidiously around it, in Latin: This blot … I stupidly made on the first of December 1482′. The books are often marvels in themselves, but they really come to life in the hands of their owners.