Generally speaking, these days, when someone says she has been on a wild goose chase, she’s been out trying to accomplish something she has come to recognize as fruitless and zany. When we use this phrase, our emphasis is on the goal, some object we have been seeking, the quarry, which has eluded us. This is strange because the clear emphasis in the phrase itself is on the process of the movement – the chase – and not on the quarry. It’s the more odd because the phrase originally did refer to the course and not to any sort of goal; the goose was not to be caught, but its erratic and unpredictable flight imitated. Geese come into it because when wild geese migrate, those following the leader will imitate and pursue its every move, no matter how erratic or unpredictable. Thus a “wild goose chase” described a country sport in which a follower was required to reproduce the exact movements of a leader, or a horse race in which the second rider had to direct his horse in just those motions and gestures set, as a pattern, by the first. Over time, its true purpose having been forgotten, the phrase was taken to refer to a course without a purpose, “a foolish, fruitless, or hopeless quest” (OED, “wild goose chase”, n. 2); the phrase’s focus on the course at the expense of the goal was taken to be a flaw, rather than the point of the experience.

I was on a wild goose chase this afternoon, in the Cambridge University Library. Due to space limitations, in places the classification system no longer corresponds to the physical organization of the books on the shelf, and by a series of imperfectly visible notices you may be led from a truncated series on one shelf, to another part of the library, from there to a window, from the window to a far corner, from the corner to a rebate behind an elevator shaft, and so on until at last you discover that the object of your increasingly abject desire – and the desire has of course been growing exponentially in proportion to your frustration – is somewhere in use, by someone else. This is a wild goose chase in both senses: an absurd and erratic dance, orchestrated by the librarian who, discarding notices in his wake, has preceded you; and a fruitless and zany quest for a fugitive end.

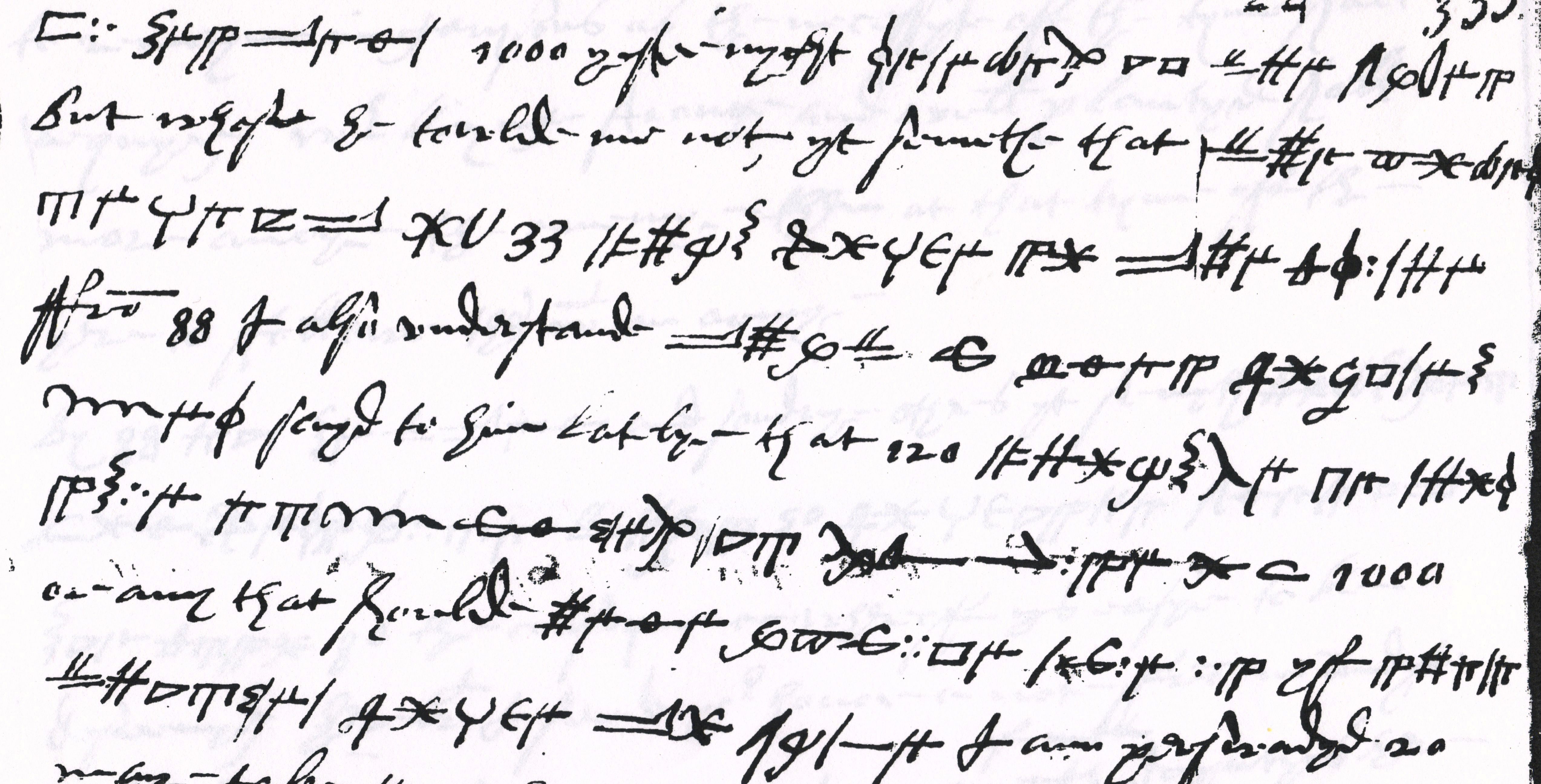

It so happens that the book I was looking for contains an essay on early modern codes and ciphers, and their use in the manuscript letters of the period. In particular, it deals with the the almost inexplicable fact that most of these codes are remarkably, even incredibly, straightforward. Even a wild goose wouldn’t be fooled. A simple alphanumeric substitution, especially one that proceeds linearly from a=1 to z=26, was unlikely to detain Sir Thomas Phelippes for very long. So why bother? It may be, say some, that the goal was not to deceive or confuse prying eyes, but to lead the reader on a satisfyingly sociable wild goose chase; that is, if I use a cipher, you must get out your key and decipher it, following every step I take, in a way that brings us together. We may look like a couple of dumb birds, but we look like a couple of dumb birds. Share the key with a small community of like-minded friends, co-religionists, or conspirators, and you have a gaggle, or what scholars call an epistolary community.

This kind of socially constructive practice turns on the materiality of the things that pass between people – the material letter with its material marks, the physical book in its lovingly prepared oubliette. I have no doubt that the scholars on South Front 4 this afternoon had watched a succession of agitated, swearing colleagues bustle from notice to notice around the University Library stacks, and in some sense we were brought closer together by the experience. Quite apart from the book that I ought now to be reading (reader: I found it somewhere else), these professional and educational rituals have an interest in their own right, for they are the ceremonies that we perform around the sacred or devotional objects at the centre of our intellectual pursuits. By contrast, the fragmentation of scholarly communities through the deprecation of material texts, and the gradual transformation of libraries into internet workstations, deprives us of our wild goose chases, and of the ritually enacted performances that construct us as a social group, and create bonds of affection, trust, and communication between us. The instant gratification characteristic of online databases – those that hold citations, journal articles, scanned books, and copies of rare printed and manuscript material – collapses the race and the chase into a single step. Everything is so much faster and less frustrating, it’s true; but all the same, everything is so much faster, and so less frustrating. It needs no Michel come from Montaigne to tell us that difficulty increases desire, nor to tell us this:

C’est, au demeurant, une très utile science que la science de l’entregent. Elle est, comme la grace et la beauté, conciliatrice des premiers abords de la societé et familiarité; et par consequent nous ouvre la porte à nous instruire par les exemples d’autruy, et à exploiter et produire nostre exemple; s’il a quelque chose d’instruisant et communicable. [The knowledge of entertainment is otherwise a profitable knowledge. It is, as grace and beautie are, the reconciler of the first accoastings of society and familiarity: and by consequence, it openeth the entrance to instruct us by the example of others, and to exploit and produce our example, if it have any instructing or communicable thing in it.] (Montaigne, “Ceremonie de l’entreveuë des Roys”, Essais, 1.13)

Now for my book.