University of Vienna, 23-25 April 2014

Keynote Speakers: Thomas Wallnig (University of Vienna) and Howard Hotson (University of Oxford)

CALL FOR PAPERS

Paper and panel proposals are invited for Scientiae 2014, the third annual conference on the emergent knowledge practices of the early modern period (ca. 1450-1750). The conference will take place on the 23-25 April 2014 at the University of Vienna in Austria, building upon the success of Scientiae 2012(Simon Fraser University) and Scientiae 2013 (Warwick), each of which brought together more than 100 scholars from around the world.

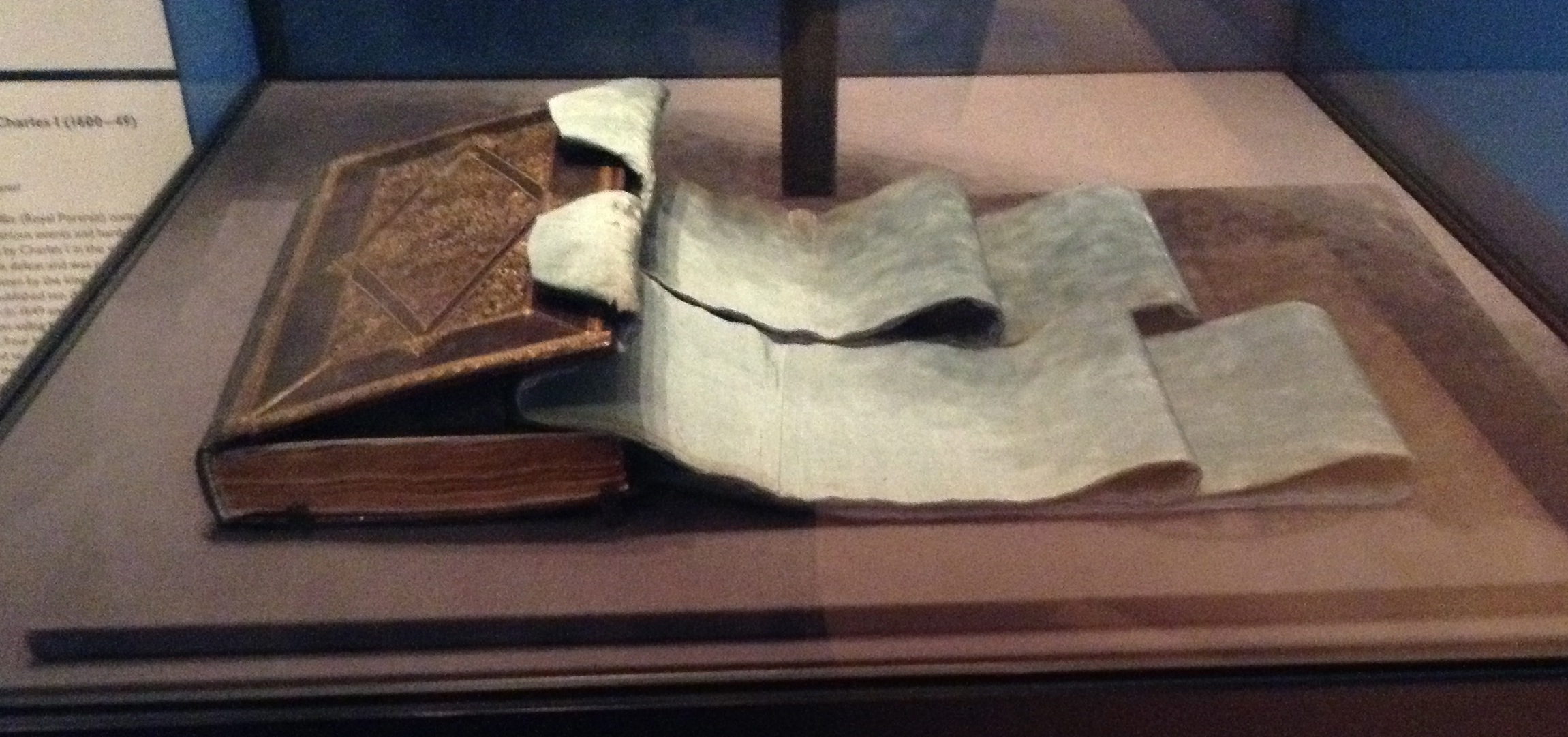

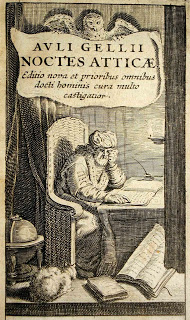

The premise of this conference is that knowledge during the period of the Scientific Revolution was inherently interdisciplinary, involving complex mixtures of practices and objects which had yet to be separated into their modern “scientific” hierarchies. Our approach, subsequently, needs to be equally wide-ranging, involving Biblical exegesis, art theory, logic, and literary humanism; as well as natural philosophy, alchemy, occult practices, and trade knowledge. Attention is also given to mapping intellectual geographies through the tools of the digital humanities. Scientiae is intended for scholars working in any area of early-modern intellectual culture, but is centred around the emergence of modern natural science. The conference offers a forum for the dissemination of research, acts as a catalyst for new investigations, and is open to scholars of all levels.

Topics may include, but are not limited to:

- Intellectual geography: networks, intellectual history, and the digital humanities.

- Theological origins and implications of the new sciences.

- Interpretations of nature and the scriptures.

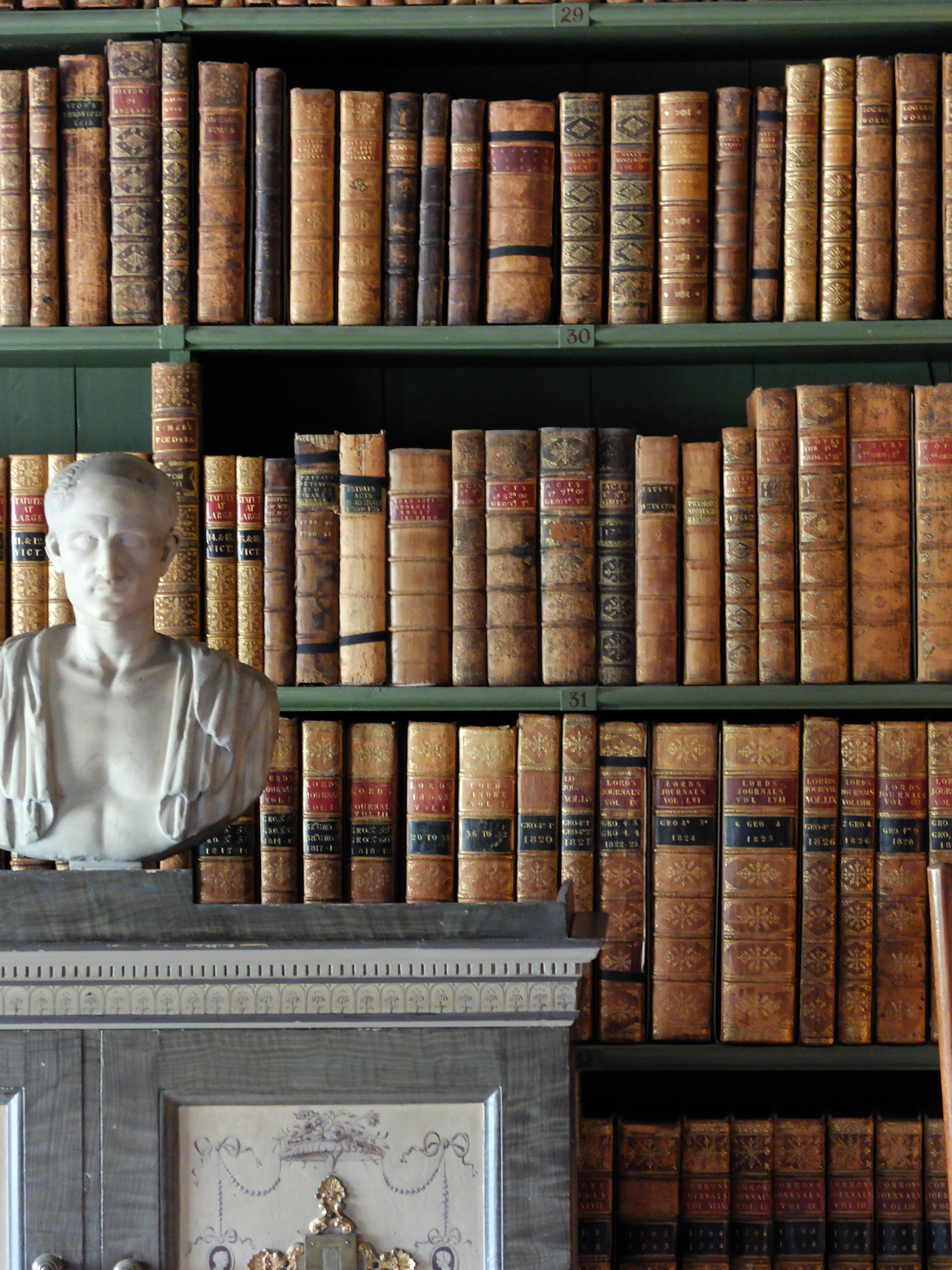

- Antiquarianism and the emergence of modern science.

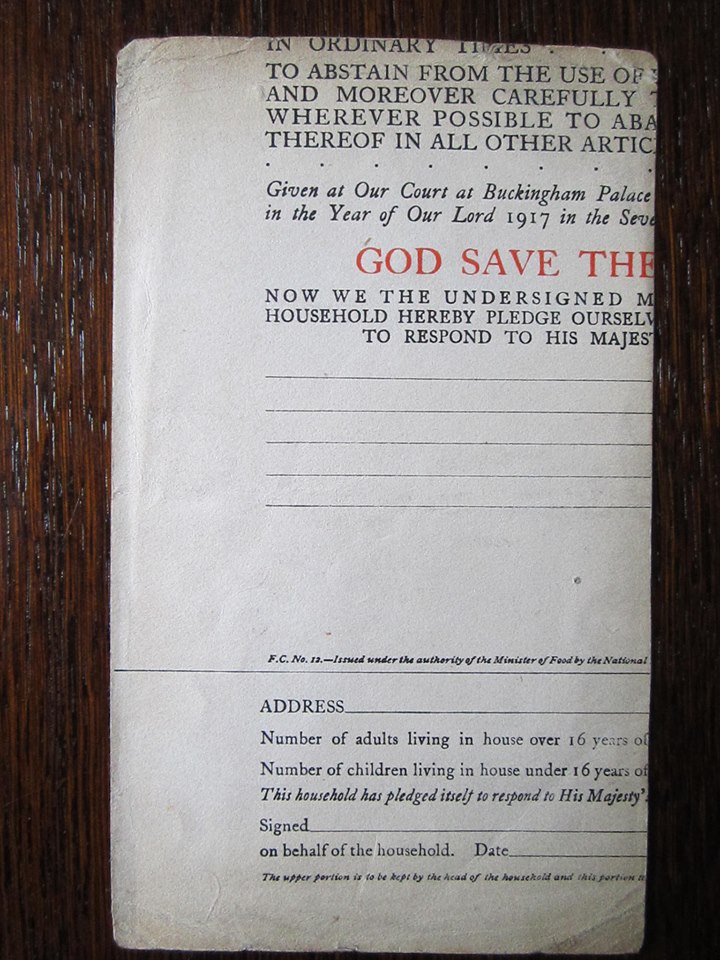

- The impact of images on the formation of early modern knowledge.

- Genealogies of “reason”, “utility”, and “knowledge”.

- Humanism and the Scientific Revolution.

- Paracelsianism, Neoplatonism, and alchemy more generally.

- Interactions between the new sciences, magic and demonology.

- The history of health and medicine.

- Morality and the character of the natural world.

- Early modern conceptions of, and practices surrounding, intellectual property.

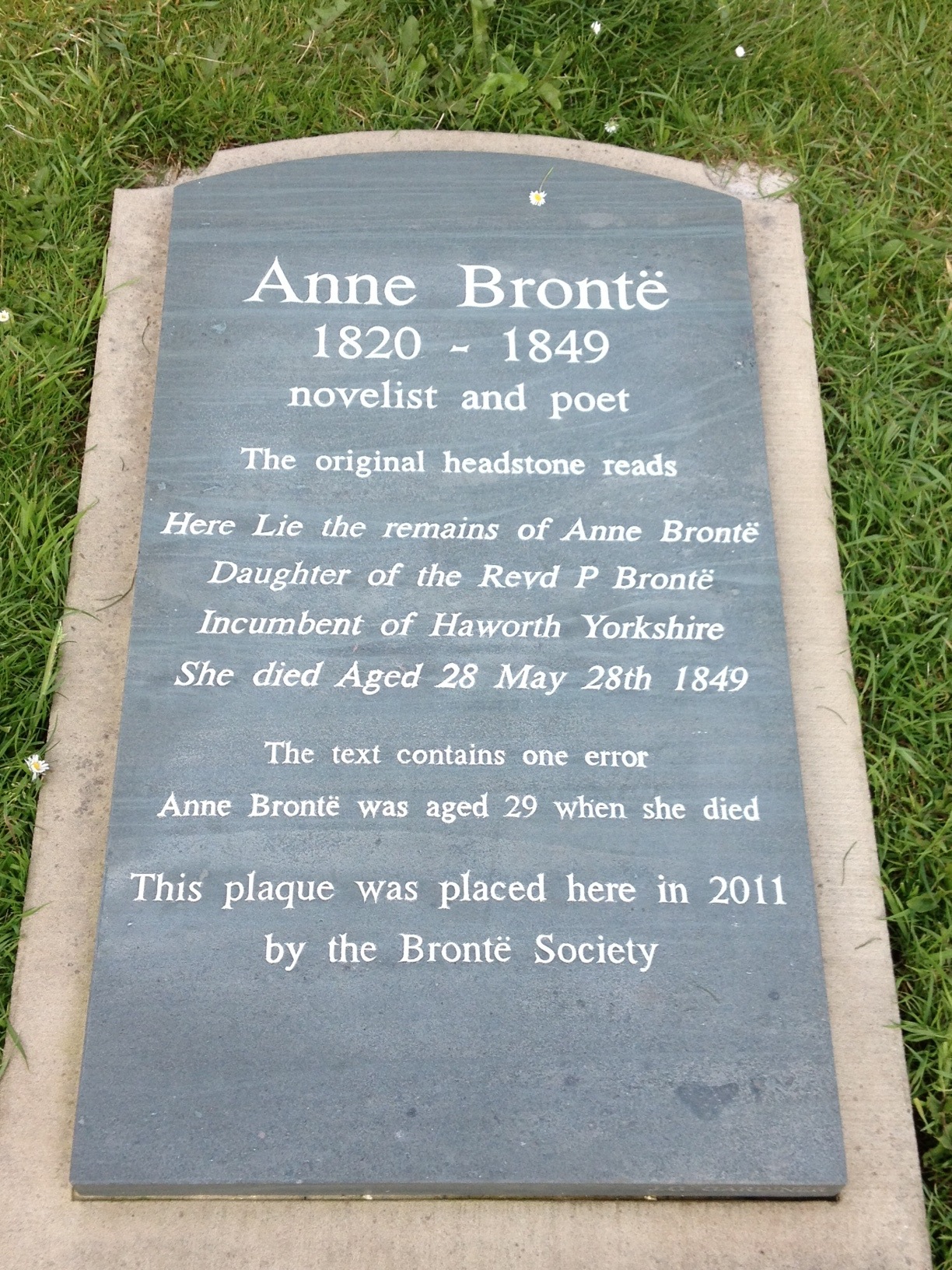

- Poetry and the natural sciences.

- The development of novel approaches to cosmology and anthropology.

- Botany: between natural history, art, and antiquarianism.

- Music: between mathematics, religion, and medicine.

- The relationship between early modern literature and knowledge.

- Advances or reversals of logic and/or dialectic.

Abstracts for individual papers of 25 minutes should be between 250 and 350 words in length. For panel sessions of 1 hour and 45 minutes, a list of speakers (with affiliations), as well as a 500-word abstract, is required. Roundtable discussions or other formats may be accepted at the discretion of the organizing committee. All applicants are also required to submit a brief biography of 150 words of less. Abstracts must be submitted through our online submission form by 15 October 2013. If you have any questions, please contact the conference convenor, Vittoria Feola (vittoria.feola@meduniwien.ac.at).

The 2014 conference will be held in the Juridicum at the University of Vienna, a modern conference building which is part of the ancient University of Vienna, founded in 1365. The conference will take place in the historic city centre of one of Europe’s most beautiful capitals, easy to reach by plane and train.