Kasia Boddy will be speaking at a symposium on American Work in Oxford on May 18th.

Author: admin (Page 10 of 10)

Malachi will be the respondent for a discussion on Literature and Nation between Cornel West and Ben Okri on May 9th.

A symposium on Christine Brooke-Rose (with John Calder, Brian Dillon, Natalie Ferris, Tom McCarthy, Rick Poynor and Ali Smith) at the Royal College of Art on April 19th. View post

View post

Rob Macfarlane will be disc ussing his book The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot at WordFest on 13th April.

ussing his book The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot at WordFest on 13th April.

Today Margaret Thatcher died, no doubt prompting numerous new books, films, and sentimental summings up. But I’ve been trying to think what, to date, we might consider the most memorable responses to Thatcherism. Boys From the Blackstuff made a big impression on me back in 1982 (although I haven’t seen it in a while); I wonder if that’ll be shown again in tribute! Never mind – Yosser’s Story is on YouTube: http://youtu.be/0CRXnO9v0sA

Today Margaret Thatcher died, no doubt prompting numerous new books, films, and sentimental summings up. But I’ve been trying to think what, to date, we might consider the most memorable responses to Thatcherism. Boys From the Blackstuff made a big impression on me back in 1982 (although I haven’t seen it in a while); I wonder if that’ll be shown again in tribute! Never mind – Yosser’s Story is on YouTube: http://youtu.be/0CRXnO9v0sA

Or, if you’ve only a minute or two: http://youtu.be/aObZJN9zDtA

Post by Kasia Boddy

The deadline for proposals for the Writing South Africa Now conference is April 8th.

‘Of whom and of what are we contemporaries? What does it mean to be contemporary?’

James Riley introduced Giorgio Agamben’s “What Is the Contemporary?” from What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford University Press, 2009):

Agamben interprets the contemporary as an experience of profound dissonance:

‘Contemporariness is, then, a singular relationship with one’s own time, which adheres to it and, at the same time, keeps a distance from it. More precisely, it is that relationship with time that adheres to it, through a disjunction and an anachronism.’

Such a quote reminds us of the frequent elision that occurs between the conceptualisation of the ‘modern’ and the categorization of the ‘contemporary’. The terms are not synonyms. To be ‘contemporary’ is to experience a state of proximity with one’s temporality. In his discussion, Agamben attempts to articulate the idea that the contemporary is an ahistorical concept; not a label of periodization, but an existential marker. This perspective foregrounds the critical importance of context and re-contextualisation when forming and understanding of ‘contemporary literature’. For Agamben, the mode of thought that this position demands is one that involves an integral epistemological difficulty:

The contemporary is he who firmly holds his gaze on his own time so as to perceive not its light, but rather its darkness. All eras, for those who experience contemporariness, are obscure. The contemporary is precisely the person who knows how to see this obscurity, who is able to write by dipping his pen in the obscurity of the present.

Contemporaneity as the perception of darkness. Agamben’s language is not without its own rhetorical obscurity at this point, but for a dramatization of the perspective he outlines we might look to Heart of Darkness. Historically it is a ‘modern’ novel but in its particular incorporation of narration, proximity and obscurity it encapsulates and also speaks from a point of con / temporal extimacy.

Kasia Boddy introduced ‘The Theory Generation’ by Nicholas Dames, which appeared in n+1 in October 2012 and which begins:

Kasia Boddy introduced ‘The Theory Generation’ by Nicholas Dames, which appeared in n+1 in October 2012 and which begins:

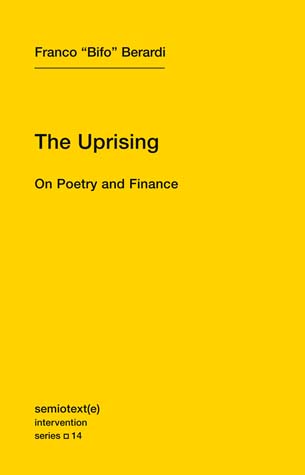

‘If you studied the liberal arts in an American college anytime after 1980, you were likely exposed to what is universally called Theory. Perhaps you still possess some recognizable talismans: that copy of The Foucault Reader, with the master’s bald head and piercing eyes emblematic of pure intellection; A Thousand Plateaus with its Escher-lite line-drawing promising the thrills of disorientation; the stark, sickly-gray spine of Adorno’s Negative Dialectics; a stack of little Semiotext(e) volumes bought over time from the now-defunct video rental place. Maybe they still carry a faint whiff of rebellion or awakening, or (at least) late-adolescent disaffection. Maybe they evoke shame (for having lost touch with them, or having never really read them); maybe they evoke disdain (for their preciousness, or their inability to solve tedious adult dilemmas); maybe they’re mute. But chances are that, of those studies, they are what remain. And you can walk into the homes of friends and experience the recognition, wanly amusing or embarrassing, of finding the very same books. If so, you belong to what might be called the Theory Generation; and it has recently become evident that some of its members have been thinking back on their training.’

Dames goes on to discuss the influence of an education (or cult initiation) in big-T Theory during ‘the long 1980s’ on the likes of Jennifer Egan, Jeffrey Eugenides, Ben Lerner, Sam Lipstye and Lorrie Moore. Their novels, he argues, are ‘peculiar novels of ideas’ in which realism ultimately ‘has its revenge’ on a particulalrly rarified academic education. And yet that education retains some value, he concludes: ‘it habituates you to the anomic, precarious existence you were destined to lead in any case. It was like a drug after all: not hallucinogenic or mind-expanding, but rather pleasantly sedating.’

10 writers from 9 countries are announced as finalists for the 2013 Man Booker International Prize. The country with 2 is, unsurprisingly, the US, but then who could begrudge Lydia Davis or Marilynne Robinson.