Bizarre news the other day on BBC Radio 4’s The World at One (now available as a written feature on the BBC website). Verifiable figures are not available, but French firms – perhaps as many as 50% of them – continue to employ graphologists in recruitment processes. Applicants must submit a sample of their handwriting, which is then submitted to the ‘experts’ for analysis.

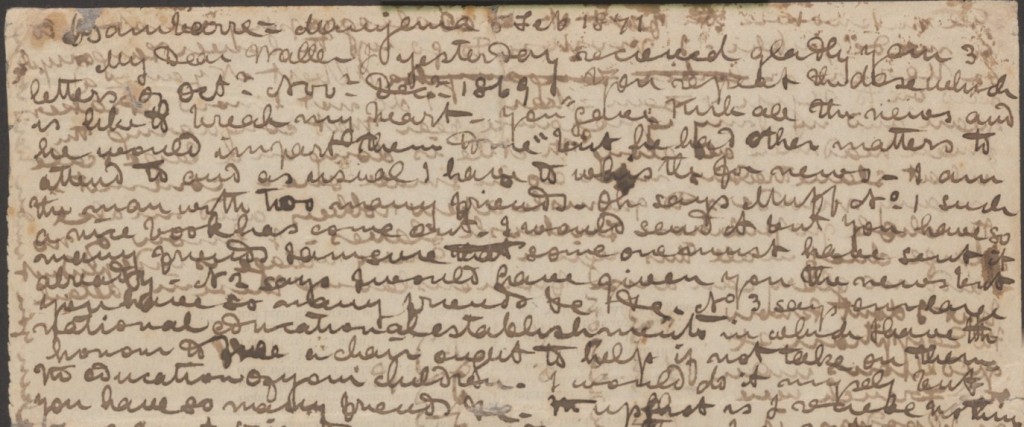

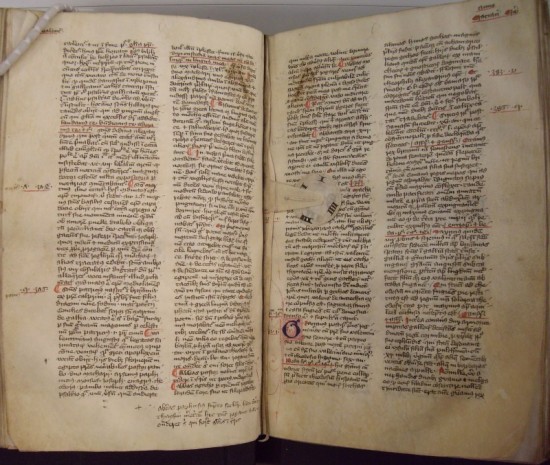

I don’t doubt that handwriting analysis can have specific practical or scholarly applications. I imagine the well-established techniques used by palaeographers to identify archaising scripts (or, conversely, to identify manuscripts copied by the same hand) – attention to the minute idiosyncrasies of letter formation and the duct of the scribes’ handwriting – aren’t too different to those involved in proving a modern forgery. Since such identifications can be the subject of scholarly disagreement, any ambitious claims for modern handwriting analysis need to be viewed with considerable scepticism.

Any attempt to apply graphology in the realms of psychology or medicine, however, just seems like bald charlatanism to me. Even where the stakes are far lower – in this case, occupational recruitment – I’m far from convinced of its usefulness. Like astrologers, chiromancers or psychics, graphologists stick to the vague and avoid the specific, and use evidence already given to them by the person they’re reading: literally, in this case, since graphologists usually study a handwritten personal statement rather than a neutral piece of writing and have spectacularly failed to give accurate descriptions when confronted with a neutral sample of handwriting.

The French attachment to graphology is a cultural one – they invented it, so it’s not surprising they remain attached to it – but it is used elsewhere, in Germany, Switzerland and Israel. Psychometric tests were, in their modern form, an American invention and remain more popular in the Anglophone world, though not to the exclusion of graphology. Indeed, graphology may be catching on on this side of La Manche. A growing number of companies justify its use as an additional screening tool because it is cheap and they claim it offers a fresh perspective on a candidate that CVs do not.

Could this perception that the manuscript word is more ‘personal’ than the printed or digital word – at a time when the future relationship between all three remains unclear – be a reaction against recruitment processes that have been rendered increasingly impersonal by e-mailed CVs and the use of online application systems? A 1990 report by the Law Society Gazette cautioned that – regardless of doubts about graphology’s credibility – European law states that submitted applications are the property of the recruiter. He or she may legally (though perhaps not ethically) send it for analysis without acquiring the applicant’s consent. So, when you’re next asked to provide something in manuscript – caveat scriptor! – you’ve no idea where it might end up.