The Gospel Book of St. Cuthbert is arguably one of the most important surviving medieval manuscripts, and it is a cause for celebration that it has been secured by the British Library in a purchase from the collection of Stonyhurst College in Lancashire. The procurement was funded by a number of major grants of public money as well as many smaller donations from the public at large. It is appropriate, then, that the book has been digitised in full and made available free-of-charge to all on the British Library’s website, as part of a project to inform and educate a broader audience about the book’s importance.

The Gospel Book of St. Cuthbert is arguably one of the most important surviving medieval manuscripts, and it is a cause for celebration that it has been secured by the British Library in a purchase from the collection of Stonyhurst College in Lancashire. The procurement was funded by a number of major grants of public money as well as many smaller donations from the public at large. It is appropriate, then, that the book has been digitised in full and made available free-of-charge to all on the British Library’s website, as part of a project to inform and educate a broader audience about the book’s importance.

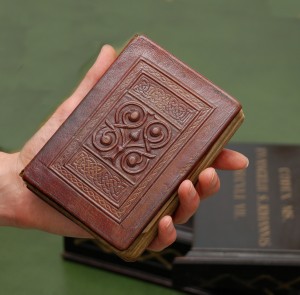

In a world where even relatively recent artworks command multi-million pound auction prices (a version of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, up for sale in New York, is expected to fetch around £50 million), the purchase of the Gospels for £9 million seems like quite the bargain. It is an outwardly modest thing – encased in a plain binding of red leather, and measuring at only 14 x 9 cm it is small enough to fit comfortably in one’s hand – yet it stands at the centre of a 1300-year-old story of the life and legend of a northern saint.

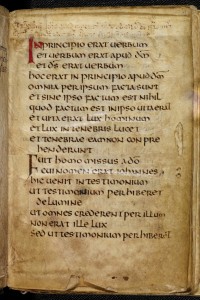

Cuthbert was born c.635, and lived his adult life as a monk in various foundations in the north of England, becoming most closely associated with Lindisfarne (where he was prior and later bishop) and Inner Farne (where he spent most of his later life as a hermit until his death on 20th March 687). The Gospel Book that takes his name is of obvious codicological importance: it dates from the late seventh century and is the earliest intact European book in existence, ‘the only surviving high-status manuscript from this crucial period in British history to retain its original appearance, both inside and out’, with the original binding enclosing the text of St. John’s Gospel, likewise unaltered since it was produced.

Yet also, just as in the medieval period, it is the association with St. Cuthbert that lends this book its particular fascination. It was placed in Cuthbert’s tomb at Lindisfarne when it was first opened in 698, and remained alongside the body of the saint until the tomb was opened again at Durham Cathedral Priory in 1104, an event witnessed by the chronicler Symeon of Durham. The book was found, according to a thirteenth-century inscription in the book, ‘near the head of our blessed father Cuthbert lying in his tomb’.

The tomb had been moved out of Lindisfarne in the eighth century, and the body and book together were carried by the community of monks around northern England, then to Chester-le-Street and eventually to Durham. The wanderings of the Gospel Book continued after the destruction of the tomb in the sixteenth century: it was donated to the English Jesuit community at Liège in the eighteenth century, was briefly misplaced while on loan to the Society of Antiquaries in the early nineteenth century, and has eventually come to rest at the British Library (where its new classmark – Add. MS 89000 – scarcely hints at the book’s importance).

When Cuthbert’s tomb was first opened in 698, it was found that ‘the skin had not decayed nor grown old, nor the sinews become dry…but the limbs lay at rest with all the appearance of life’. The incorruptability of a body was crucial evidence in the canonization process, and (whether accurate or not) such accounts are repeated over and again in medieval hagiographies. Holy books, too, were imbued with similar properties of indestructability: according to Symeon, the Lindisfarne Gospels (also at the British Library) were washed overboard during a voyage across the Irish Sea but were found miraculously unharmed on the shore. Few librarians nowadays would be willing to trust the safety of their collections to the intervention of a guardian saint!

It is the vulnerability of manuscripts to damage or destruction that makes the survival of the Gospel Book of St. Cuthbert in such excellent condition so remarkable – dare we say, even miraculous? The historical significance of the book would be no less diminished if it were damaged – but the smoothness of its bindings, the cleanness of its pages and the crispness of its written text cannot but mark it out as exceptional, even though its survival in this state is the outcome of historical chance. To what degree are aesthetic appreciation and scholarly study complementary? Is the Gospel Book of St. Cuthbert powerful as a physical (if not religious) relic of the past because of its unblemished state? In tracing the provenance of a manuscript – like the provenance of a medieval relic – are we seeking more than simple identification and verification? Perhaps a tangible physical connection with the past? Or the privilege of seeing and touching something that is now just as it was more than a millenium ago?