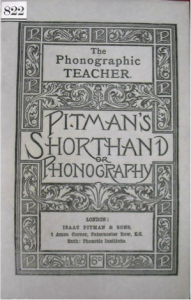

Isaac Pitman’s phonographic shorthand or ‘sound-hand’ was invented in 1837 and remains the mostly widely used system of shorthand in the world, now more commonly known as ‘Pitman Shorthand.’

Isaac Pitman’s phonographic shorthand or ‘sound-hand’ was invented in 1837 and remains the mostly widely used system of shorthand in the world, now more commonly known as ‘Pitman Shorthand.’

Shorthand – otherwise known as stenography, brachygraphy, or tachygraphy – is a system of written signs designed to enable their user to write words down at the rate at which they are spoken. The earliest known form of shorthand is found in the ‘Tironian Notes’, developed by Marcus Tullius Tiro in order to quickly and accurately transcribe Cicero’s speeches. Later English-language systems include: Timothy Bright’s Characterie: An Arte of Shorte, Swifte and Secrete Writing by Character (1588), Thomas Shelton’s Short Writing (1626) (used by Samuel Pepys in his diaries), and Samuel Taylor’s 1786 system. Taylor’s system was widely used throughout the English-speaking world and the young Isaac Pitman mastered it before developing his own system.

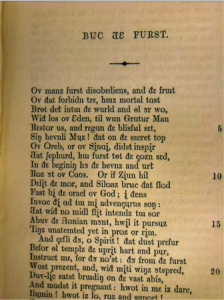

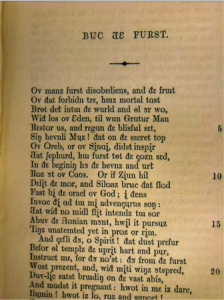

These shorthand systems were primarily orthographic, using particular marks to indicate common clusters of letters – prefixes, suffixes, common endings, and everyday words – although they also often included marks representing vowel-sounds. Pitman’s innovation was to invent a shorthand system with a strictly phonetic basis. Phonographic shorthand transcribed sound rather than abbreviated spelling: it bypassed conventional orthography in order to give written form to the accents and inflections of pronunciation. As Pitman himself put it, phonographic shorthand was a system of writing in which the ‘very sound of every word is made VISIBLE.’

Pitman’s specific concern was to develop a system of shorthand in which audible speech – rather than just its linguistic meaning – could be perfectly reproduced from written signs. His interest in the relationship between texts and pronunciation began at a young age: coming across unknown words in Paradise Lost, he discovered that he could reconstruct their correct stress and intonation from Milton’s prosody. This interest remained with him, prompting the development and endless refinement of phonographic shorthand, and eventually leading him to establish his Phonetic Institution which was to become the headquarters of the Spelling Reform movement and the centre for its many publishing and pedagogical activities.

Pitman’s specific concern was to develop a system of shorthand in which audible speech – rather than just its linguistic meaning – could be perfectly reproduced from written signs. His interest in the relationship between texts and pronunciation began at a young age: coming across unknown words in Paradise Lost, he discovered that he could reconstruct their correct stress and intonation from Milton’s prosody. This interest remained with him, prompting the development and endless refinement of phonographic shorthand, and eventually leading him to establish his Phonetic Institution which was to become the headquarters of the Spelling Reform movement and the centre for its many publishing and pedagogical activities.

While there is sometimes a mismatch between Pitman’s pedagogical ambition for the system and its actual success, the development of his long-distance learning programme indicates the level of popular engagement with phonographic shorthand. Every Phonetic Institute publication advertised that ‘Any Person may receive lessons from the Author by post gratuitously. Each lesson must be enclosed in a paid letter. The pupil can write about a dozen verses from the Bible, leaving spaces between the lines for corrections.’ By 1845, Pitman was receiving 10,000 phonographic letters a year. Similarly, while the ‘Phonetic Sunday Schools’ that Pitman imagined would be central to the education of children in phonetic literacy seem never to have been established, phonographic shorthand was nevertheless used on the mission field to produce the first written records of un-transcribed languages, including Bengalee, Tongan, and Malagasy. There were also reports that the system was used to take notes in the Chinese Parliament

The extent of popular engagement with phonographic shorthand is indicated here, as is its global reach, and some of the ways it influenced literacy, engagement with educational activities, and understandings of language. Despite this, there has been very little investigation into the use of the system or its significance for how we think about writing and language more broadly in the nineteenth-century. The Rare Books Department at Cambridge University Library has an extensive collection of Phonetic Institution publications, including teaching materials, exercise books, phonotypic publications, and phonetic periodicals. Much of this material has never been studied, and many of the books still have their pages uncut. There is, I think, some very interesting work to be done here.

Pitman’s endeavour also reflects the proliferation of phonographic experiments and the growing concerns about language in the nineteenth-century. Attempts to inscribe sound in such a way t hat it could be reproduced took many different forms. Alexander Melville Bell, a professor of physiological phonetics at Edinburgh, developed a system of ‘Visible Speech’ in which grammalogues depicting the shapes of sound in the human mouth were used to teach the profoundly deaf correct pronunciation. His son, Alexander Graham Bell, was such an accomplished reader of ‘Visible Speech’ that his party-trick was to use ‘Visible Speech’ transcriptions to read out loud foreign texts in languages he couldn’t speak (includng Sanskrit and Gaelic) to the satisfaction of native speakers. A. G. Bell subsequently developed the telephone (patented 1875-77). Thomas Edison invented the phonograph (the precursor to the gramophone) in 1877 which made re-playable voice-recordings by tracing a vibrating needle over wax cylinders. Turning from technological experiments to linguistic research, concerns with accurately recording the sound of speech were central to nineteenth-century investigations into philology, etymology, and regional accent. They also play out in the dialect poetry of Dorset poet William Barnes, and can, I argue, be traced in Thomas Hardy’s preoccupation with disembodied voices and forms of inscription (see ‘‘How you call to me, call to me’: Hardy’s Self-Remembering Syntax’, Victorian Poetry, Spring 2016).

hat it could be reproduced took many different forms. Alexander Melville Bell, a professor of physiological phonetics at Edinburgh, developed a system of ‘Visible Speech’ in which grammalogues depicting the shapes of sound in the human mouth were used to teach the profoundly deaf correct pronunciation. His son, Alexander Graham Bell, was such an accomplished reader of ‘Visible Speech’ that his party-trick was to use ‘Visible Speech’ transcriptions to read out loud foreign texts in languages he couldn’t speak (includng Sanskrit and Gaelic) to the satisfaction of native speakers. A. G. Bell subsequently developed the telephone (patented 1875-77). Thomas Edison invented the phonograph (the precursor to the gramophone) in 1877 which made re-playable voice-recordings by tracing a vibrating needle over wax cylinders. Turning from technological experiments to linguistic research, concerns with accurately recording the sound of speech were central to nineteenth-century investigations into philology, etymology, and regional accent. They also play out in the dialect poetry of Dorset poet William Barnes, and can, I argue, be traced in Thomas Hardy’s preoccupation with disembodied voices and forms of inscription (see ‘‘How you call to me, call to me’: Hardy’s Self-Remembering Syntax’, Victorian Poetry, Spring 2016).

As such, Pitman’s phonographic shorthand also offers an insight into a particular historical moment in which these questions about the relation between texts and sounds were at the forefront of technological and linguistic research. Establishing the relationship between text and sound was not only a practical problem. It also pressed philosophical questions about the nature of meaning – about the relationship between linguistic sense and sensuous form, about what writing is for and how it relates to speech, and about the kinds of sound, experience, and meaning that become available when we read.

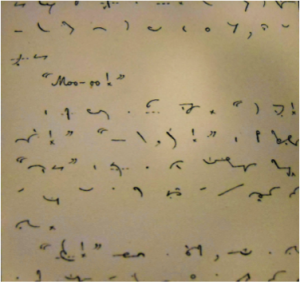

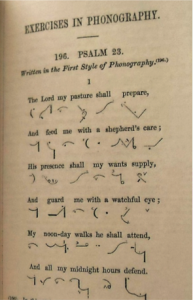

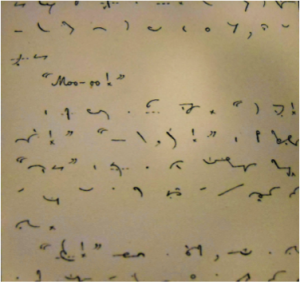

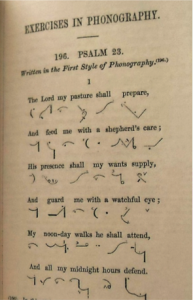

Some of the philosophical thinking about language that attended Pitman’s innovations can be seen in his phonographic books. They show an anxiety that we might not be able to hear the difference between different categories of sound and language when all noise is inscribed as the same kind of phonographic text: in the phonographic edition of Thankful Blossom: A Romance of the Jerseys, 1779, by Bret Harte (1889), Pitman – bizarrely – leaves the cow’s moo-ing untranscribed; similarly, in Plutarch’s Lives of Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar (1887), Pitman leaves all Latin names untranslated. In the ‘Exercises in Phonography’ appended to A Manual of Phonography (1845), Pitman seems to take particular delight in demonstrating how his phonographic system makes the end-rhymes of the metrical psalm visible as a sequence of paired symbols.

But these questions about the relation between text and voice also raise philosophical questions about the nature of human identity: the relationship between voice and presence, between being and knowing, between embodied life and the traces of human experience and knowledge we leave behind. Edison, with a mixture of pride and sadness, acknowledged the extent to which these phonographic experiments raise questions that intrude on and threaten the self-reflexive knowing that constitutes the sense of self: ‘The phonograph, in one sense, knows more than we do ourselves. For it will retain a perfect mechanical memory of many things which we may forget, even though we have said them’.

But these questions about the relation between text and voice also raise philosophical questions about the nature of human identity: the relationship between voice and presence, between being and knowing, between embodied life and the traces of human experience and knowledge we leave behind. Edison, with a mixture of pride and sadness, acknowledged the extent to which these phonographic experiments raise questions that intrude on and threaten the self-reflexive knowing that constitutes the sense of self: ‘The phonograph, in one sense, knows more than we do ourselves. For it will retain a perfect mechanical memory of many things which we may forget, even though we have said them’.

Anna Nickerson

An exhibition of Pitman-related materials is currently on display on the first floor lobby of the Faculty of English, 9 West Rd.

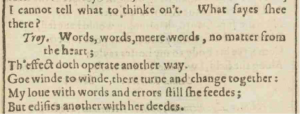

There are a few moments in Shakespeare that capture these aspects of paper. Amid the utter bleakness of the ending of Troilus and Cressida, Troilus receives a letter from Cressida. We never find out what it says; Troilus dismisses the contents as ‘words, words, mere words, no matter from the heart’, before tearing it up. ‘Goe wind to wind, there turn and change together’. The fluttering of the paper becomes a visual metaphor for what Troilus perceives to be his beloved’s faithlessness.

There are a few moments in Shakespeare that capture these aspects of paper. Amid the utter bleakness of the ending of Troilus and Cressida, Troilus receives a letter from Cressida. We never find out what it says; Troilus dismisses the contents as ‘words, words, mere words, no matter from the heart’, before tearing it up. ‘Goe wind to wind, there turn and change together’. The fluttering of the paper becomes a visual metaphor for what Troilus perceives to be his beloved’s faithlessness. Isaac Pitman’s phonographic shorthand or ‘sound-hand’ was invented in 1837 and remains the mostly widely used system of shorthand in the world, now more commonly known as ‘Pitman Shorthand.’

Isaac Pitman’s phonographic shorthand or ‘sound-hand’ was invented in 1837 and remains the mostly widely used system of shorthand in the world, now more commonly known as ‘Pitman Shorthand.’ Pitman’s specific concern was to develop a system of shorthand in which audible speech – rather than just its linguistic meaning – could be perfectly reproduced from written signs. His interest in the relationship between texts and pronunciation began at a young age: coming across unknown words in Paradise Lost, he discovered that he could reconstruct their correct stress and intonation from Milton’s prosody. This interest remained with him, prompting the development and endless refinement of phonographic shorthand, and eventually leading him to establish his Phonetic Institution which was to become the headquarters of the Spelling Reform movement and the centre for its many publishing and pedagogical activities.

Pitman’s specific concern was to develop a system of shorthand in which audible speech – rather than just its linguistic meaning – could be perfectly reproduced from written signs. His interest in the relationship between texts and pronunciation began at a young age: coming across unknown words in Paradise Lost, he discovered that he could reconstruct their correct stress and intonation from Milton’s prosody. This interest remained with him, prompting the development and endless refinement of phonographic shorthand, and eventually leading him to establish his Phonetic Institution which was to become the headquarters of the Spelling Reform movement and the centre for its many publishing and pedagogical activities. hat it could be reproduced took many different forms. Alexander Melville Bell, a professor of physiological phonetics at Edinburgh, developed a system of ‘Visible Speech’ in which grammalogues depicting the shapes of sound in the human mouth were used to teach the profoundly deaf correct pronunciation. His son, Alexander Graham Bell, was such an accomplished reader of ‘Visible Speech’ that his party-trick was to use ‘Visible Speech’ transcriptions to read out loud foreign texts in languages he couldn’t speak (includng Sanskrit and Gaelic) to the satisfaction of native speakers. A. G. Bell subsequently developed the telephone (patented 1875-77). Thomas Edison invented the phonograph (the precursor to the gramophone) in 1877 which made re-playable voice-recordings by tracing a vibrating needle over wax cylinders. Turning from technological experiments to linguistic research, concerns with accurately recording the sound of speech were central to nineteenth-century investigations into philology, etymology, and regional accent. They also play out in the dialect poetry of Dorset poet William Barnes, and can, I argue, be traced in Thomas Hardy’s preoccupation with disembodied voices and forms of inscription (see ‘‘How you call to me, call to me’: Hardy’s Self-Remembering Syntax’, Victorian Poetry, Spring 2016).

hat it could be reproduced took many different forms. Alexander Melville Bell, a professor of physiological phonetics at Edinburgh, developed a system of ‘Visible Speech’ in which grammalogues depicting the shapes of sound in the human mouth were used to teach the profoundly deaf correct pronunciation. His son, Alexander Graham Bell, was such an accomplished reader of ‘Visible Speech’ that his party-trick was to use ‘Visible Speech’ transcriptions to read out loud foreign texts in languages he couldn’t speak (includng Sanskrit and Gaelic) to the satisfaction of native speakers. A. G. Bell subsequently developed the telephone (patented 1875-77). Thomas Edison invented the phonograph (the precursor to the gramophone) in 1877 which made re-playable voice-recordings by tracing a vibrating needle over wax cylinders. Turning from technological experiments to linguistic research, concerns with accurately recording the sound of speech were central to nineteenth-century investigations into philology, etymology, and regional accent. They also play out in the dialect poetry of Dorset poet William Barnes, and can, I argue, be traced in Thomas Hardy’s preoccupation with disembodied voices and forms of inscription (see ‘‘How you call to me, call to me’: Hardy’s Self-Remembering Syntax’, Victorian Poetry, Spring 2016). But these questions about the relation between text and voice also raise philosophical questions about the nature of human identity: the relationship between voice and presence, between being and knowing, between embodied life and the traces of human experience and knowledge we leave behind. Edison, with a mixture of pride and sadness, acknowledged the extent to which these phonographic experiments raise questions that intrude on and threaten the self-reflexive knowing that constitutes the sense of self: ‘The phonograph, in one sense, knows more than we do ourselves. For it will retain a perfect mechanical memory of many things which we may forget, even though we have said them’.

But these questions about the relation between text and voice also raise philosophical questions about the nature of human identity: the relationship between voice and presence, between being and knowing, between embodied life and the traces of human experience and knowledge we leave behind. Edison, with a mixture of pride and sadness, acknowledged the extent to which these phonographic experiments raise questions that intrude on and threaten the self-reflexive knowing that constitutes the sense of self: ‘The phonograph, in one sense, knows more than we do ourselves. For it will retain a perfect mechanical memory of many things which we may forget, even though we have said them’.