On 1 May 2015, the Centre for Material Texts sponsored a colloquium on the subject of visual marginalia—the annotation of books with pictures rather than (or as well as) words. In the Middle Ages, scribes often decorated the margins of their texts with images, which sometimes bore an ironic or subversive relationship to the words they accompanied. Our colloquium, organized by Dr Alexander Marr from the Department of History of Art, focused on a later period (the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries), and on images added by later readers rather than by the initial producers of texts.

On 1 May 2015, the Centre for Material Texts sponsored a colloquium on the subject of visual marginalia—the annotation of books with pictures rather than (or as well as) words. In the Middle Ages, scribes often decorated the margins of their texts with images, which sometimes bore an ironic or subversive relationship to the words they accompanied. Our colloquium, organized by Dr Alexander Marr from the Department of History of Art, focused on a later period (the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries), and on images added by later readers rather than by the initial producers of texts.

The images that renaissance readers left in their books took many forms. One of the most common was the pointing hand, or manicule, that served to direct attention to a particular passage. Some scholars used astrological symbols to make the themes of a book visible—Mars for war, Venus for love, Mercury for wit and so on. Others added illustrations marking references to particular places, individuals and events. Once a whole volume had been ‘digested’ in this way, the margins would function as a kind of running contents list that made information retrieval easy and pleasurable. Then there are a few prestige books, such as the copy of Erasmus’s Praise of Folly that was illustrated by Hans Holbein, which can be considered works of art in their own right.

Julian Luxford (History of Art, St Andrews) opened the colloquium by drawing attention to the sheer variety of kinds of visual marginalia, and the difficulty of locating, describing and understanding them. Showing a range of examples, from pictures that seemed to be executed by trainee artists to sexual images perhaps added by bored schoolboys, Luxford suggested that it was time to stop thinking of these marginalia as ‘doodles’ or ‘pen-trials’. However amateurish they may seem, we should take them seriously as evidence for the visual culture of the period. He also wondered whether we should be talking about ‘margins’–a term with a lot of ideological baggage–or should think instead of ‘borders’, a term which forces us to think about what lay beyond the boundaries of the page.

The study of visual marginalia is sometimes challenging by design, as when early modern readers created esoteric pictorial schemes that elude our best efforts to make sense of them. In their contribution to the colloquium, Alex Marr and Kate Isard (Visiting Scholar, Cambridge) discussed the copy of Vincenzo Cartari’s Imagini (1581) now in the Houghton Library at Harvard. This book has been annotated extensively in Dutch, Latin and French, and has been illustrated with a series of astrological, alchemical, mock-heraldic and downright lewd images that are at once wonderfully bizarre and exceptionally difficult to decode. The volume presents an ongoing puzzle and a provocation to further research.

The study of visual marginalia is sometimes challenging by design, as when early modern readers created esoteric pictorial schemes that elude our best efforts to make sense of them. In their contribution to the colloquium, Alex Marr and Kate Isard (Visiting Scholar, Cambridge) discussed the copy of Vincenzo Cartari’s Imagini (1581) now in the Houghton Library at Harvard. This book has been annotated extensively in Dutch, Latin and French, and has been illustrated with a series of astrological, alchemical, mock-heraldic and downright lewd images that are at once wonderfully bizarre and exceptionally difficult to decode. The volume presents an ongoing puzzle and a provocation to further research.

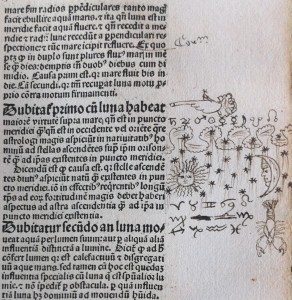

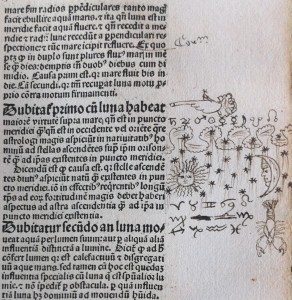

Other kinds of visual marginalia were technical and professional. In his talk, Richard Oosterhoff (Cambridge) explored the schoolbooks of the German humanist Beatus Rhenanus, in which we can see him ‘thinking through diagrams’ about the relationship between mathematics and the nature of reality. Francesco Benelli (Columbia) turned our attention to a tiny diagram–less than one inch square–that the Renaissance architect Antonio da Sangallo the Younger added in the margins of his copy of Vitruvius’s treatise on architecture, marking his misunderstanding of the text in ways that went on to influence the buildings he created. These papers suggested the fecundity and the difficulty of the process of translating words into images, which is manifested when readers start to draw in the margins.

In the wake of the colloquium, the CMT has assembled a small exhibition, currently on display in the University Library entrance hall, of books with images on the edge. The four books shown here were all discovered by Kate Isard and Liam Sims in a recent search of the Cambridge rare book stacks. For those who can’t make it to the UL to see them, here they are:

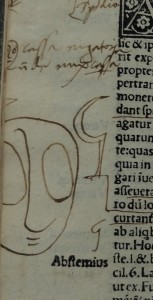

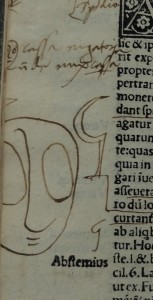

Adv.c.25.1: faces in the margins

This is a copy of a treatise on poetry and poetics by the Italian humanist Giovanni Francesco Conti (1484-1557), published in Venice in 1519. An unknown early reader engaged closely with the text, adding dense underlining and numerous verbal annotations. More unusually, the reader added roughly-drawn faces of different sizes, along with marks that could perhaps be interpreted as scythes. These symbols may be intended merely to flag up passages of interest, but it is possible that they serve some more specific purpose. They are certainly not part of the standard repertory of reader annotation, and they give the book—which has unfortunately been heavily cropped during rebinding—a very distinctive appearance.

This is a copy of a treatise on poetry and poetics by the Italian humanist Giovanni Francesco Conti (1484-1557), published in Venice in 1519. An unknown early reader engaged closely with the text, adding dense underlining and numerous verbal annotations. More unusually, the reader added roughly-drawn faces of different sizes, along with marks that could perhaps be interpreted as scythes. These symbols may be intended merely to flag up passages of interest, but it is possible that they serve some more specific purpose. They are certainly not part of the standard repertory of reader annotation, and they give the book—which has unfortunately been heavily cropped during rebinding—a very distinctive appearance.

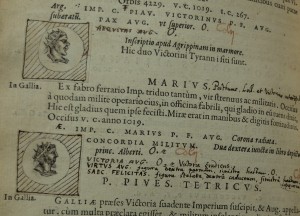

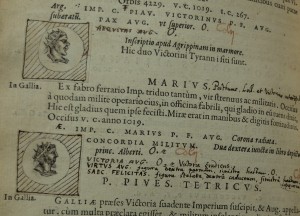

Adv.d.3.22: picturing the past

This catalogue of Roman imperial coins was compiled by the German numismatist Adolf Occo (1524-1606), and was printed in Antwerp by Christopher Plantin. It was published at the author’s expense, and perhaps to save money it had no illustrations. This copy was bought in Antwerp by James Cole in August 1588. Cole was a London silk merchant, a member of a Huguenot immigrant family and a nephew of the celebrated mapmaker Abraham Ortelius. He was a dedicated collector of rarities, including plants, fossils, coins and medals. Cole interleaved his copy of Occo’s book with numerous blank pages which he used to supplement the information provided in the printed text. He also pasted in illustrative portraits of each emperor, conspicuously improving on the original book. This sort of customization was not unusual in a period when books were sold unbound in sheets, to be put together by their purchasers. The detail and precision of Cole’s interventions reveal his intense curiosity about the classical past.

This catalogue of Roman imperial coins was compiled by the German numismatist Adolf Occo (1524-1606), and was printed in Antwerp by Christopher Plantin. It was published at the author’s expense, and perhaps to save money it had no illustrations. This copy was bought in Antwerp by James Cole in August 1588. Cole was a London silk merchant, a member of a Huguenot immigrant family and a nephew of the celebrated mapmaker Abraham Ortelius. He was a dedicated collector of rarities, including plants, fossils, coins and medals. Cole interleaved his copy of Occo’s book with numerous blank pages which he used to supplement the information provided in the printed text. He also pasted in illustrative portraits of each emperor, conspicuously improving on the original book. This sort of customization was not unusual in a period when books were sold unbound in sheets, to be put together by their purchasers. The detail and precision of Cole’s interventions reveal his intense curiosity about the classical past.

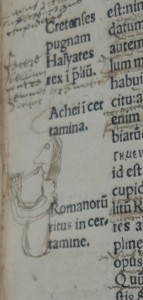

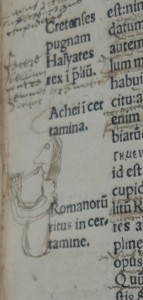

Td.54.32: an absurd image?

The second-century Latin author Aulus Gellius is known for a single work, the Noctes Atticae or Attic Nights, a compilation of miscellaneous information which preserves many excerpts from classical works that are now lost. This edition was published in Paris in around 1512. An early reader has added notes in Latin not just in the margins, but also in between the closely-packed lines of print. The style of the annotations suggests that they may have been penned by a student recording a teacher’s glosses upon the text. There are also scattered drawings in the margins, including this picture of a piper or flautist. The drawing accompanies Gellius’ description of a king who sent his armies into battle along with orchestras of pipe- and lyre-players ‘and even female flute-players, such as are the delight of wanton banqueters’. Perhaps it was the strangeness of this notion that prompted a visual response.

The second-century Latin author Aulus Gellius is known for a single work, the Noctes Atticae or Attic Nights, a compilation of miscellaneous information which preserves many excerpts from classical works that are now lost. This edition was published in Paris in around 1512. An early reader has added notes in Latin not just in the margins, but also in between the closely-packed lines of print. The style of the annotations suggests that they may have been penned by a student recording a teacher’s glosses upon the text. There are also scattered drawings in the margins, including this picture of a piper or flautist. The drawing accompanies Gellius’ description of a king who sent his armies into battle along with orchestras of pipe- and lyre-players ‘and even female flute-players, such as are the delight of wanton banqueters’. Perhaps it was the strangeness of this notion that prompted a visual response.

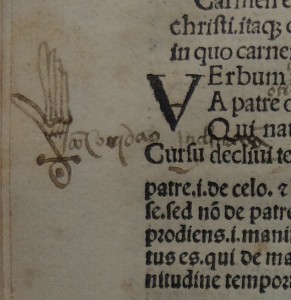

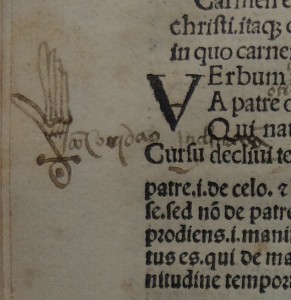

Td.56.2: some handy hymns

Antonio de Nebrija (1441-1522) was a Spanish Renaissance scholar who became a widely-published author; among his works was a Castilian grammar that was the first printed grammar of a vernacular language. This book, a commentary on liturgical hymns, went through numerous editions (our example was printed at Logroño in northern Spain). An early reader made copious linguistic notes on the text of the hymns, finding Spanish equivalents for Latin words and phrases. They also added manicules (pointing hands) to note particular passages, and on this page they drew a number of hands with the fingers pointing upwards. Since these appear at the beginnings of the three hymns discussed here, their purpose was presumably to make the structure of the printed book more evident to its reader.

Antonio de Nebrija (1441-1522) was a Spanish Renaissance scholar who became a widely-published author; among his works was a Castilian grammar that was the first printed grammar of a vernacular language. This book, a commentary on liturgical hymns, went through numerous editions (our example was printed at Logroño in northern Spain). An early reader made copious linguistic notes on the text of the hymns, finding Spanish equivalents for Latin words and phrases. They also added manicules (pointing hands) to note particular passages, and on this page they drew a number of hands with the fingers pointing upwards. Since these appear at the beginnings of the three hymns discussed here, their purpose was presumably to make the structure of the printed book more evident to its reader.

Yesterday we learnt that Philip Larkin is to be given a memorial in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner. The stone will be unveiled on 2 December 2016, the 31st anniversary of his death.

Yesterday we learnt that Philip Larkin is to be given a memorial in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner. The stone will be unveiled on 2 December 2016, the 31st anniversary of his death.

The study of visual marginalia is sometimes challenging by design, as when early modern readers created esoteric pictorial schemes that elude our best efforts to make sense of them. In their contribution to the colloquium, Alex Marr and Kate Isard (Visiting Scholar, Cambridge) discussed the copy of Vincenzo Cartari’s Imagini (1581) now in the Houghton Library at Harvard. This book has been annotated extensively in Dutch, Latin and French, and has been illustrated with a series of astrological, alchemical, mock-heraldic and downright lewd images that are at once wonderfully bizarre and exceptionally difficult to decode. The volume presents an ongoing puzzle and a provocation to further research.

The study of visual marginalia is sometimes challenging by design, as when early modern readers created esoteric pictorial schemes that elude our best efforts to make sense of them. In their contribution to the colloquium, Alex Marr and Kate Isard (Visiting Scholar, Cambridge) discussed the copy of Vincenzo Cartari’s Imagini (1581) now in the Houghton Library at Harvard. This book has been annotated extensively in Dutch, Latin and French, and has been illustrated with a series of astrological, alchemical, mock-heraldic and downright lewd images that are at once wonderfully bizarre and exceptionally difficult to decode. The volume presents an ongoing puzzle and a provocation to further research.

This catalogue of Roman imperial coins was compiled by the German numismatist Adolf Occo (1524-1606), and was printed in Antwerp by Christopher Plantin. It was published at the author’s expense, and perhaps to save money it had no illustrations. This copy was bought in Antwerp by James Cole in August 1588. Cole was a London silk merchant, a member of a Huguenot immigrant family and a nephew of the celebrated mapmaker Abraham Ortelius. He was a dedicated collector of rarities, including plants, fossils, coins and medals. Cole interleaved his copy of Occo’s book with numerous blank pages which he used to supplement the information provided in the printed text. He also pasted in illustrative portraits of each emperor, conspicuously improving on the original book. This sort of customization was not unusual in a period when books were sold unbound in sheets, to be put together by their purchasers. The detail and precision of Cole’s interventions reveal his intense curiosity about the classical past.

This catalogue of Roman imperial coins was compiled by the German numismatist Adolf Occo (1524-1606), and was printed in Antwerp by Christopher Plantin. It was published at the author’s expense, and perhaps to save money it had no illustrations. This copy was bought in Antwerp by James Cole in August 1588. Cole was a London silk merchant, a member of a Huguenot immigrant family and a nephew of the celebrated mapmaker Abraham Ortelius. He was a dedicated collector of rarities, including plants, fossils, coins and medals. Cole interleaved his copy of Occo’s book with numerous blank pages which he used to supplement the information provided in the printed text. He also pasted in illustrative portraits of each emperor, conspicuously improving on the original book. This sort of customization was not unusual in a period when books were sold unbound in sheets, to be put together by their purchasers. The detail and precision of Cole’s interventions reveal his intense curiosity about the classical past.