Julia M. H. Smith is giving the Birkbeck lectures at Trinity this year, dates and titles as below. Julia is currently planning on holding an open seminar on the day after the final lecture, particularly for interested graduate and early career researchers, to pick up on the topics arising from her talks, details of which will follow closer to the time.

Julia Smith (Chichele Professor of Medieval History, University of Oxford) on ‘Christianity in Fragments: the Formation of the Cult of Relics, c. 300-800.’

5 February: ‘Refashioning the Holy Land’

12 February: ‘Material Blessings’

19 February: ‘Protecting Body and Soul’

26 February: ‘Martyrs, Bones and Bodies’

All lectures take place in the Winstanley Lecture Theatre at 5.00 pm

History of Material Texts Seminar, Lent Term 2018

January 21st, 2018Seminar Series; Jason Scott-Warren

Thursday 8 February, 5 pm, Board Room, Faculty of English

Stewart J. Brookes (Cambridge), ‘Archetype: A Digital Humanities Approach to Medieval Script and Iconography’

Thursday 22 February, 5 pm, Board Room, Faculty of English

Tiffany Stern (Shakespeare Institute), ‘Playing Songs and Singing Plays: Ballads and Plays in the Time of Shakespeare’

Thursday 8 March, 5 pm, Board Room, Faculty of English

Anne Toner (Cambridge), ‘Jane Austen’s Chapters’

All welcome

A snap from the second of David Pearson’s masterclasses on early modern bookbindings, held last week in the Cambridge University Library. The classes were a reminder that a rare books library is an extraordinary collection of dead animal skins, a mausoleum for the thousands of pigs, sheep, cows and goats that gave their lives in part to make words on paper more durable. The sessions were also an encounter with the mystery of design, as they traced the changing decorative fashions that allow a trained eye to date a binding quite precisely to a particular period.

Somewhere inside me I still have a logocentric self that thinks bindings don’t matter–they are just there to serve the words. Perhaps that is reinforced by the fact that the vast majority of bindings are distinctly plain and functional, turning the book into something sturdy and everyday. But to face up to the scale of the premodern binding trade, and of the extraordinary price-differentiation of the products that it produced, is to realise that books were once choice objects, things to flash around as evidence of wealth, taste and social status. Our thanks to David for making this sometimes arcane world accessible once more.

I’ve just written a blog-post for the Cambridge University Library rare books site, on an extraordinary seventeenth-century book that was the library’s first purchase from ebay. You can read it here:

https://specialcollections.blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=15246

author.net: A cross-divisional conference on distributed authorship

October 11th, 2017Calls for Papers, News; Jason Scott-WarrenUCLA, October 5th-6th 2018

Organizers:

Sean Gurd, Professor of Classics, University of Missouri

Francesca Martelli, Assistant Professor of Classics, UCLA

DEADLINE FOR ABSTRACTS: January 15, 2018

Distributed authorship is a familiar concept in many fields of cultural production. Long associated with pre-modern cultures, it still serves as a mainstay for the study of Classical antiquity, which takes ‘Homer’ as its foundational point of orientation, and which, like many other disciplines in the humanities, has extended its insights into the open-endedness of oral and performance traditions into its study of textual dynamics as well. The rise of genetic criticism within textual studies bears witness to this urge to fray perceptions of the hermetic closure of the written, and to expose the multiple strands of collaboration and revision that a text may contain. And the increasingly widespread use of the multitext in literary editions of authors from Homer to Joyce offers a material manifestation of this impulse to display the multiple different levels and modes of distribution at work in the authorial process. In many areas of the humanities that rely on traditional textual media, then, the distributed author is alive and well, and remains a current object of study.

In recent years, however, the dynamic possibilities of distributed authorship have accelerated most rapidly in media associated with the virtual domain, where modes of communication have rendered artistic creation increasingly collaborative, multi-local and open-ended. These developments have prompted important questions on the part of scholars who study these new media about the ontological status of the artistic, musical and literary objects that such modes of distribution (re)create. In musicology, for example, musical modes such as jazz improvisation and digital experimentation are shown to exploit the complex relay of creativity within and between the ever-expanding networks of artists and audiences involved in their production and reception, and construct themselves in ways that invite others to continue the process of their ongoing distribution. The impact of such artistic developments on the identity of ‘the author’ may be measured by developments in copyright law, such as the emergence of the Creative Commons, an organization that enables artists and authors to waive copyright restrictions on co-creators in order to facilitate their collaborative participation. And this mode of distribution has in turn prompted important questions about the orientation of knowledge and power in the collectives and publics that it creates.

This conference seeks to deepen and expand the theorising of authorial distribution in the virtual domain, and to explore the insights that its operations in this sphere might lend into the mechanisms of authorial distribution at work in older (and, indeed, ancient) media. To this end, it will bring together scholars working in the fields of communication and information technology with scholars working across the humanities, in order to explore what kind of dialogue we might generate on the question of distributed authorship across these disciplinary (and other) divisions. Ultimately, our aim is to develop and refine a set of conceptual tools that will bring distributed authorship into a wider remit of familiarity; and to explore whether these tools are, in fact, unique to the new media that have inspired their most recent discursive formulation, or whether they have a range of application that extends beyond the virtual domain.

We invite contributions from those who are engaged directly with the processes and media that are pushing and complicating ideas of distributed authorship in the world today, and also from those who are actively drawing on insights derived from these contemporary developments in their interpretation of the textual and artistic processes of the past, on the following topics (among others):

- The distinctive features of the new artistic genres and objects generated by modes of authorial distribution, from musical mashups to literary centones.

- The impact that authorial distribution has on the temporality of its objects, as the multiple agents that form part of the distribution of those objects spread the processes of their decomposition/re-composition over time.

- The re-orienting of power relations that arises from the distribution of authorship among networks of senders and receivers, as also from the collapsing of ‘sender’ and ‘receiver’ functions into one another.

- The modes of ‘self’-regulation that authorial collectives develop in order to sustain their identity.

- Fandom and participatory culture, in both virtual and traditional textual media.

- The operational dynamics of ‘multitexts’ and ‘text networks’, and their influence by and on virtual networks.

Paper proposals will be selected for their potential to open up questions that transcend the idiom of any single medium and/or discipline. Please send a proposal of approximately 500 words to gurds@missouri.edu by January 15, 2018.

Confirmed participants include:

Mario Biagioli, Distinguished Professor of Law and Science and Technology Studies, and director of the Centre for Science and Innovation Studies, UC Davis (author of Galileo Courtier, Chicago 1993; and editor, with Peter Galison, of Scientific Authorship, Routledge 2003).

Georgina Born, Professor of Music and Anthropology, Oxford University (director of Music, Digitisation, Mediation: Towards Interdisciplinary Music Studies, or MusDig: http://musdig.music.ox.ac.uk).

Christopher Kelty, Professor of Anthropology, Information Studies, and at the Institute for Society and Genetics, UCLA (author of Two Bits: the Cultural Significance of Free Software, Duke 2008).

Scott McGill, Professor of Classics, Rice University (author of Virgil Recomposed: the Mythological and Secular Centos in Antiquity, Oxford 2005; and Plagiarism in Latin Literature, Cambridge 2012)

Daniel Selden, Professor of Literature, UC Santa Cruz (author of numerous articles, and a forthcoming book, on the phenomenon of ‘text networks’ in the long Hellenistic period)

Fascinating article by Huang Yuan in the latest London Review of Books about the tightening of censorship regimes in China. ‘The Economist often receives phone calls from Chinese subscribers to the print edition complaining about missing issues (especially when the cover shows a panicky Xi Jinping astride a stumbling dragon). And it’s not uncommon for pages with critical reports about China to be torn from the magazine before subscribers get it (we have no shortage of manpower for this labour-intensive task). The New York Review of Books–always critical of China, and sharing many contributors with the New York Times–has so far dodged the censor, most likely because the number of subscribers is too low for the censors to condescend to’.

History of Material Texts seminars, Michaelmas 2017

October 3rd, 2017Seminar Series; Jason Scott-Warren

Thursday 26 October, 5 pm, Board Room, Faculty of English

Orietta da Rold (Cambridge), ‘A paper on (premodern) paper’

Thursday 16 November, 5 pm, Board Room, Faculty of English

John Gagné (Sydney), ‘Paper, Time, and Oblivion in Premodern Europe’

Thursday 23 November, 5 pm, Board Room, Faculty of English

Dennis Duncan (Munby Fellow, CUL), ‘Nitpickers vs Windbags: Weaponising the Book Index, 1698-1730’

Monday 27 November, 11.30 am-1 pm & Tuesday 28 November, 11.30 am-1 pm

Milstein Seminar Room, CUL

David Pearson (London), ‘Telling the sheep from the goat: a brief guide to historic bookbindings (1450-1800) for humanities researchers’

(please email jes1003@cam.ac.uk to prebook for these masterclasses)

It’s over a week now since our CMT/Southampton conference ‘Newes from No Place’, on the life and works of John Taylor, the Water-Poet (1578-1653). Held at Gonville and Caius College on 14-15 September, it featured thirteen speakers who offered many different perspectives on Taylor’s gargantuan oeuvre. We came together in the belief that Taylor, a self-professed amphibian who was at once a boatman on the river Thames (the equivalent of the London cab driver of today) and a hugely prolific writer, was an extraordinary figure in extraordinary times. Our aim was to set this incessant traveller in motion again, to see what he had to say to literary critics and cultural historians in the twenty-first century.

It’s over a week now since our CMT/Southampton conference ‘Newes from No Place’, on the life and works of John Taylor, the Water-Poet (1578-1653). Held at Gonville and Caius College on 14-15 September, it featured thirteen speakers who offered many different perspectives on Taylor’s gargantuan oeuvre. We came together in the belief that Taylor, a self-professed amphibian who was at once a boatman on the river Thames (the equivalent of the London cab driver of today) and a hugely prolific writer, was an extraordinary figure in extraordinary times. Our aim was to set this incessant traveller in motion again, to see what he had to say to literary critics and cultural historians in the twenty-first century.

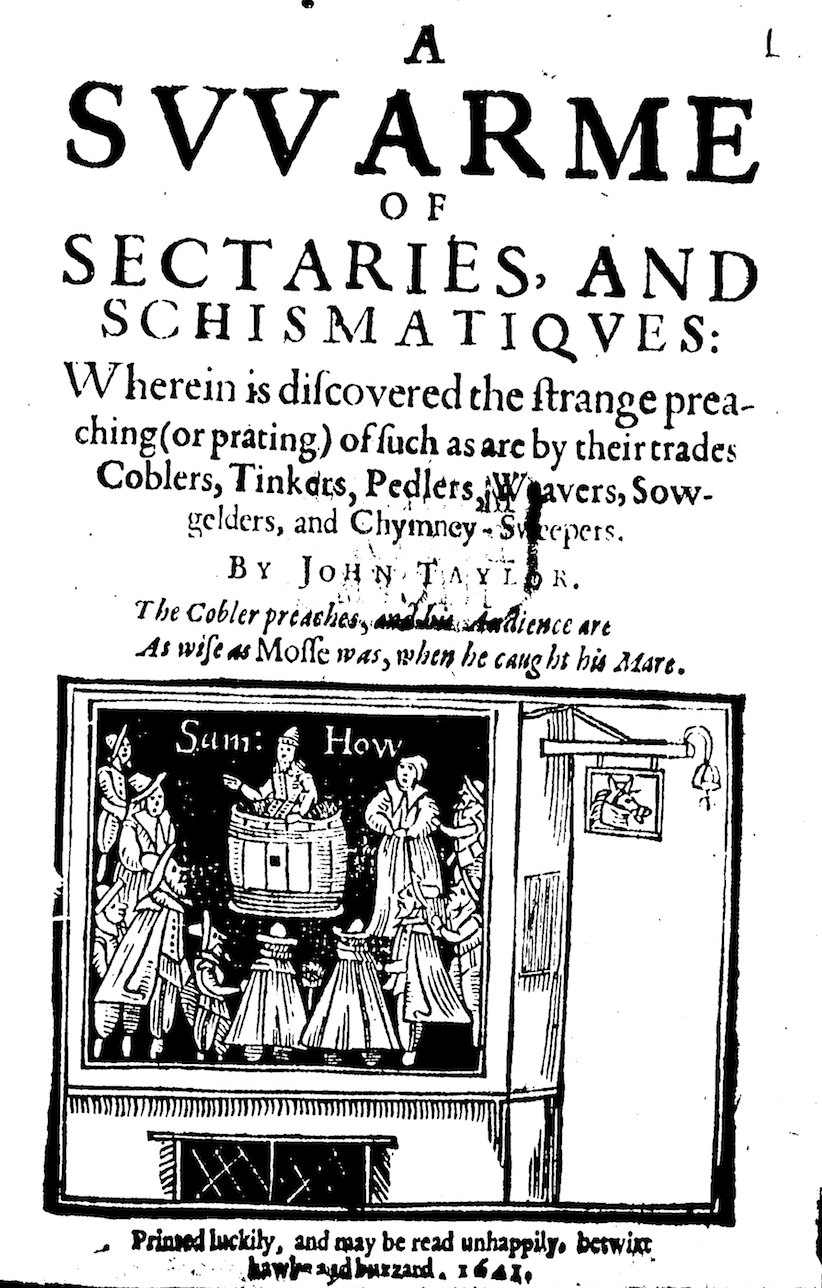

Proceedings were initiated by Bernard Capp, author of a magisterial survey of Taylor’s career, who reconsidered Taylor’s output during the Civil War years of the 1640s. Driven out of London for his Royalist sympathies, by 1643 Taylor found himself in Oxford, defending the King’s cause in pamphlets so numerous that the printing presses were unable to keep up with them. Analysing those pamphlets afresh, Capp concluded that they were not the kind of thing that might convince an adversary, but were intended to boost Royalist morale, at the same time as they settled scores with individual adversaries. One particularly resonant concern of Taylor’s was ‘fake news’; some of his pamphlets peddled their own spoof stories, while others attempted to set the record straight through first-hand reportage. After Capp had offered this wide-angle view, Abigail Shinn homed in on one pamphlet, The Conversion, Confession, Contrition, Coming to Himselfe, & Advice, of a Mis-led, Ill-bred, Rebellious Roundhead (1643). Drawing on Andrew McRae’s argument about the financial productivity of Taylor’s journeying, Shinn read this satire on a convert to puritanism as an attack on unproductive travel—spinning in circles around a ‘round head’. Parodying the puritan practice of ‘sermon-gadding’ to hear particular preachers, a staple element in spiritual life-writing of the period, Taylor’s Roundhead displays an inordinate movement linked with madness and vagrancy. Shinn showed us how that movement registers in Taylor’s style, which starts gadding wildly in imitation of its subject.

Ros King’s paper celebrated Taylor’s mobility, as a counterweight to any received picture of the early modern period as a time of stasis and social conservatism. In travelling, Taylor was finding out what it meant to be English (or British) in his day, but at the same time he was remaking social relations and experimenting with the more horizontal ties that could be created by urban life and the marketplace of print. His ability to celebrate the everyday and to overturn hierarchies (as when he got a pair of schoolboys, rather than aristocrats or men of letters, to supply the commendation for a book) points to a new vision of the social order. Challenging us to think counterfactually, King asked whether a more Taylorian Britain might not have had to endure the revolution of the 1640s.  She was followed by Ariel Hessayon, who began by announcing that he was not going to give the paper he had intended to give, because he no longer believed that the work he had planned to discuss was written by Taylor. He went on to demonstrate that numerous works of the 1640s and 1650s have been ascribed to Taylor on the flimsiest foundations (by whom is not yet clear). Taylor’s authorship has been inferred from the most tenuous evidence: a reused woodblock, some promising-looking initials (‘J.T.’ or ‘T.J.’) on the title-page, or the presence of Taylorian tricks of style that could have been borrowed by any able satirist. Invoking the spectre of the Ranter debates of the 1980s, in which historians speculated that a well-known Civil War splinter group was no more than the ‘fake news’ whipped up by the conservatives of the day, Hessayon asked whether we would prefer a maximal Taylor, who encompasses everything that has been pinned on him, however dubiously, or a minimal Taylor, who might have written none of ‘his’ works? Finding the golden mean between these extremes is going to take some time.

She was followed by Ariel Hessayon, who began by announcing that he was not going to give the paper he had intended to give, because he no longer believed that the work he had planned to discuss was written by Taylor. He went on to demonstrate that numerous works of the 1640s and 1650s have been ascribed to Taylor on the flimsiest foundations (by whom is not yet clear). Taylor’s authorship has been inferred from the most tenuous evidence: a reused woodblock, some promising-looking initials (‘J.T.’ or ‘T.J.’) on the title-page, or the presence of Taylorian tricks of style that could have been borrowed by any able satirist. Invoking the spectre of the Ranter debates of the 1980s, in which historians speculated that a well-known Civil War splinter group was no more than the ‘fake news’ whipped up by the conservatives of the day, Hessayon asked whether we would prefer a maximal Taylor, who encompasses everything that has been pinned on him, however dubiously, or a minimal Taylor, who might have written none of ‘his’ works? Finding the golden mean between these extremes is going to take some time.

The first day was rounded off by three papers, the first by Anthony Ossa-Richardson on Taylor’s learning. Drawing on Taylor’s early poetic credo in The Nipping and Snipping of Abuses (1614), Ossa-Richardson noted his opposition to mimicry; Taylor thought that the poet should be a creator-figure who produces something from nothing, and not a mere copyist or translator. He went on to analyse Taylor’s nonsense, showing how one batch of nonsense (in the 1651 Nonsence Upon Sence) creates its nonsensicality by cutting and pasting lines from an earlier, less nonsensical collection (the Mad verse, sad verse, glad verse and bad verse cut out, and slenderly sticht together of 1644). Taylor’s habits of plagiarism and self-plagiarism thus raise important questions about his aesthetic. Adam Smyth took up the baton with a consideration of Taylor and error, noting his playful way with errata lists and linking it with his wider ‘print-shop presence’, his determination to be there (‘an unsilenceable voice’) in every aspect of his books. The idea of error is also linked with wandering, and with Taylor’s identity as a traveller whose whole oeuvre is constitutively erroneous; Smyth drew attention to the strange miscellaneity of the 1630 folio All the Workes, its resistance to order or organization, and the sense that its binding together of so many miscellaneous pamphlets is also a form of scattering and dispersal. Finally in this session, Jason Scott-Warren proposed an ‘Exuvial Taylor’, drawing on the works of the anthropologist Alfred Gell to consider the writer in terms of the metaphorical ‘skins’ that he shed or re-inhabited during his lifetime. This led to a view of Taylor as a writer devoted to blazing or blazoning—the trumpeting of his own reputation and that of a range of bizarre things (geese, clean linen, twelve-pence, hemp-seed). But, Scott-Warren suggested, Taylor’s blazings are always ironic, and are thus symptomatic of a print marketplace that can put a celebrity author’s name into everyone’s mouth, but cannot ensure that they pay for his wares.

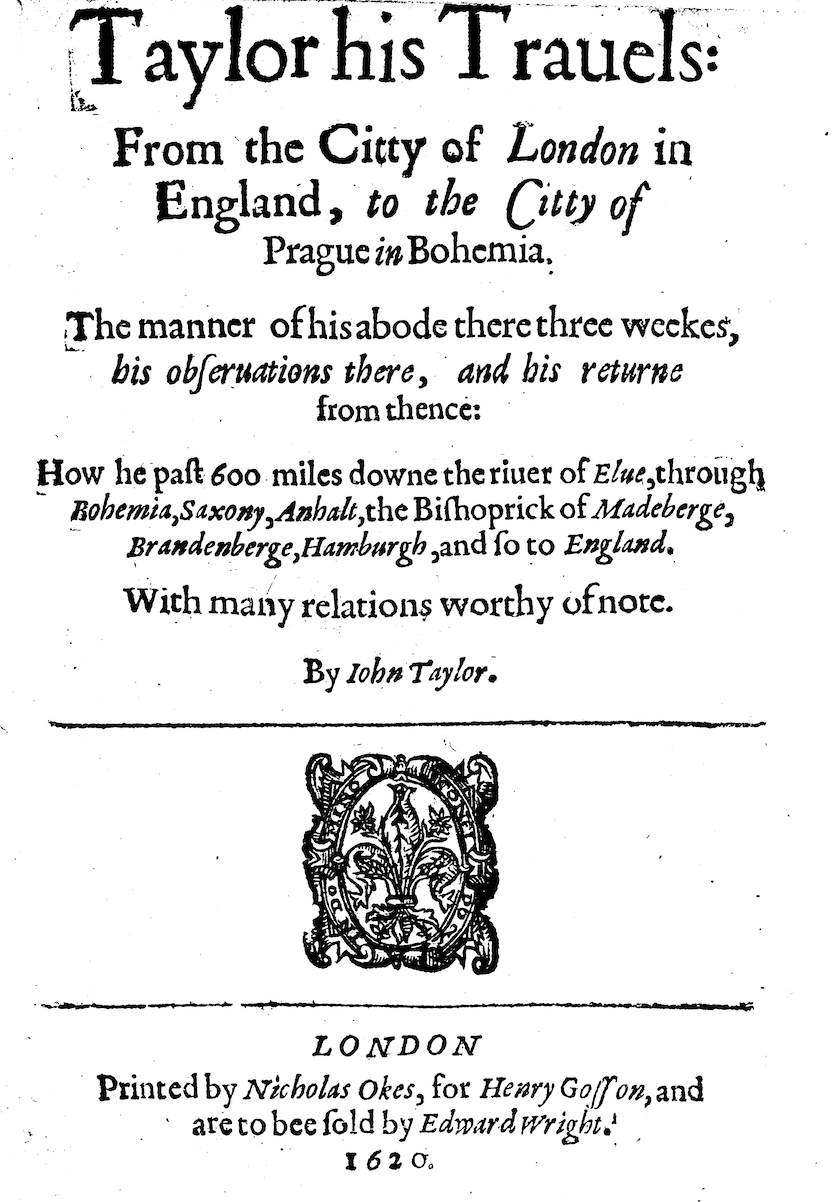

Day 2 struck out across Europe with Kirsty Rolfe’s paper on Taylor’s imagined geographies, setting his 1620 journey to Prague in the context of the news culture of the Thirty Years’ War. At this sticky political moment, when the appetite for news was at its height, James I issued a proclamation against the excess of licentious speech in matters of state—a classic case of an act of censorship that could not bring itself to say exactly what it wanted to censor. Unpicking Taylor’s satire on 1620s news culture, Rolfe suggested his sharp awareness of the intricacies of the circulation of information, and his disingenousness in claiming to stand outside it. Jemima Matthews brought us back to London and to Taylor’s Thames, including his involvement in the production of mayoral pageants, in which the river was converted into a fantastical space of performance. Such entertainments had a long tradition of broaching serious matters in the guise of theatre, and Taylor’s contribution to the genre, the 1634 Triumphs of Fame and Honour, was no exception, reminding the Mayor of his responsibilities to the river. Matthews set the pageant in relation to a variety of monopolistic schemes to exploit the river, showing how Taylor’s pamphlet contributed to the representation of the Thames as a space of financial opportunity.

Day 2 struck out across Europe with Kirsty Rolfe’s paper on Taylor’s imagined geographies, setting his 1620 journey to Prague in the context of the news culture of the Thirty Years’ War. At this sticky political moment, when the appetite for news was at its height, James I issued a proclamation against the excess of licentious speech in matters of state—a classic case of an act of censorship that could not bring itself to say exactly what it wanted to censor. Unpicking Taylor’s satire on 1620s news culture, Rolfe suggested his sharp awareness of the intricacies of the circulation of information, and his disingenousness in claiming to stand outside it. Jemima Matthews brought us back to London and to Taylor’s Thames, including his involvement in the production of mayoral pageants, in which the river was converted into a fantastical space of performance. Such entertainments had a long tradition of broaching serious matters in the guise of theatre, and Taylor’s contribution to the genre, the 1634 Triumphs of Fame and Honour, was no exception, reminding the Mayor of his responsibilities to the river. Matthews set the pageant in relation to a variety of monopolistic schemes to exploit the river, showing how Taylor’s pamphlet contributed to the representation of the Thames as a space of financial opportunity.

Andrew McRae and Alice Hunt presented papers that took us to opposite ends of Taylor’s career. McRae took on the early works (meaning the 30-odd pamphlets that he published between 1612 and 1621), showing us how Taylor became the Water-Poet, a writer who rather than effacing his origins and his occupation chose to flaunt them. Taylor began as a surprisingly well-connected writer, but in his print wars with Fenner and Coryate came increasingly to define himself by his exclusion from elite literary circles. He was also relentlessly experimental, trying out numerous genres until he began to find his metier around 1620—at which time he also learnt to equate poetry with labour, in verse that represented a reinvention of georgic. Alice Hunt explored the Taylor of the 1650s, who was (after his ejection from London) no longer a Water-Poet, but a land-traveller undertaking a kind of existential journeying in search of the identity of the new, kingless Britain. Hunt noted the weariness of the late pamphlets, Taylor ‘limping through the English countryside on a knackered nag’. But he had not lost his eye for the evocative detail, and his writing was subtle in its probing of political allegiances. Exploring Taylor’s evocation of the headless kingdom allows us to see that his royalism was not, and perhaps never had been, particularly reverend.

Will May’s paper addressed itself to Taylor’s place in the history of whimsy, via a long-term history of nonsense. Drawing on Michael Dobson’s suggestion that the history of English nonsense might be the history of works that use the word ‘Basingstoke’ for comic effect, May led us into a history of whimsy as a kind of fever of the brain—a fever that might be brought on by trying to trace the origins of the word ‘whimsy’ itself. Finally May set Taylor in a tradition of  performative, public writer-eccentrics, including Thomas Hood and Marianne Moore. Altogether less whimsical was Johann Gregory’s paper, reporting back on his recent project to live-tweet John Taylor’s travels around Wales in 1652 (#WaterPoet2017). This digital journeying was an innovative form of research that allowed Gregory to see where Taylor had elided aspects of his travels, raising questions about the faithfulness of seemingly spontaneous eyewitness accounts. But it was principally a form of public engagement that echoed Taylor’s own projects, and suggested their ongoing vibrancy in the present day. Taylor has, we suspect, many travels left in him.

performative, public writer-eccentrics, including Thomas Hood and Marianne Moore. Altogether less whimsical was Johann Gregory’s paper, reporting back on his recent project to live-tweet John Taylor’s travels around Wales in 1652 (#WaterPoet2017). This digital journeying was an innovative form of research that allowed Gregory to see where Taylor had elided aspects of his travels, raising questions about the faithfulness of seemingly spontaneous eyewitness accounts. But it was principally a form of public engagement that echoed Taylor’s own projects, and suggested their ongoing vibrancy in the present day. Taylor has, we suspect, many travels left in him.

Two stories side-by-side in yesterday’s Guardian, on the waning of print institutions.

On the left, ‘End of the line for Yellow Pages in print’ notes that, from January 2019, the distinctive bright-yellow, large-format paperback that has circulated UK business telephone numbers for more than fifty years is to cease publication. The practice of printing directories on yellow paper apparently dates back to 1883, when a printer in Cheyenne, Wyoming ran out of white paper and turned to a stock of yellow instead. (But why did he have so much yellow paper to hand?) The English version has been going since 1966, but its content will now be transferred to the online platform, yell.com, which went live in 1996. The article evokes a certain nostalgia for the old days by reproducing a still from the 1980s advertising campaign, in which an aging author by the name of J. R. Hartley used the Yellow Pages to locate a copy of his own book on fly-fishing.

To the right, ‘Cyclopaedia succumbs to digital era’. The Pears’ Cyclopaedia, “A Mass of Curious and Useful Information about Things that everyone Ought to know in Commerce, History, Science, Religion, Literature and other topics of Ordinary Conversation”, is being discontinued. The decision by the publishers, Penguin, is partly down to the retirement of its editor, Dr Chris Cook, but it tells of a slump in the market for reference books; Pears’ sold 25,000 copies in 2001-2 but only 3,000 last year. Perhaps this is a sign of liberation from somewhat oppressive strictures—we no longer think that there are things that ‘everyone Ought to know’—but more likely it tells of the speed with which we have delegated information to the Internet. The human brain declines to waste its energy remembering facts that are easily found online.

To the right, ‘Cyclopaedia succumbs to digital era’. The Pears’ Cyclopaedia, “A Mass of Curious and Useful Information about Things that everyone Ought to know in Commerce, History, Science, Religion, Literature and other topics of Ordinary Conversation”, is being discontinued. The decision by the publishers, Penguin, is partly down to the retirement of its editor, Dr Chris Cook, but it tells of a slump in the market for reference books; Pears’ sold 25,000 copies in 2001-2 but only 3,000 last year. Perhaps this is a sign of liberation from somewhat oppressive strictures—we no longer think that there are things that ‘everyone Ought to know’—but more likely it tells of the speed with which we have delegated information to the Internet. The human brain declines to waste its energy remembering facts that are easily found online.

The juxtaposition of the two articles made me feel a little melancholy, in part because they seemed to presage the demise of the very object that was relaying them to me. The Guardian is getting thinner and more expensive with every passing year; it is about to move from its rather elegant ‘Berliner’ format to a tabloid format, and this may prove to be just another staging-post on the route to its physical disappearance. Perhaps it doesn’t really matter. But my inner J.R. Hartley is a little sad to say goodbye to the bad old days when there were limits on what you could know, which created the hunger to get round them.