Few medieval manuscripts have retained their original binding; fewer still have retained such interesting features as the one visible below. Originally stitched into the spine, this simple leather strip is a material witness to fifteenth-century reading processes. It marks the page and, courtesy of the little numbered rotating paper disc, also reminds the reader to which column of text he should return upon reopening the book.

The manuscript in question – Oxford, Bodleian Library, Hatton MS 14 – is a fine fifteenth-century copy of Ranulph Higden’s Polychronicon, and it once belonged to the community of Carthusian monks at Sheen, on the banks of the Thames. It is the only Polychronicon manuscript I have seen so far with a contemporary bookmark. That these manuscripts usually come with scholarly apparatus designed to aid skim reading and ready reference – alphabetical indices, running book and chapter numbers, and marginal chronologies – suggests that this bookmark cannot have been unique among copies of Higden’s universal chronicle. It is a rare illustration of the union of material and textual book design, and the response of bespoke medieval book producers to the common intellectual needs of their customers.

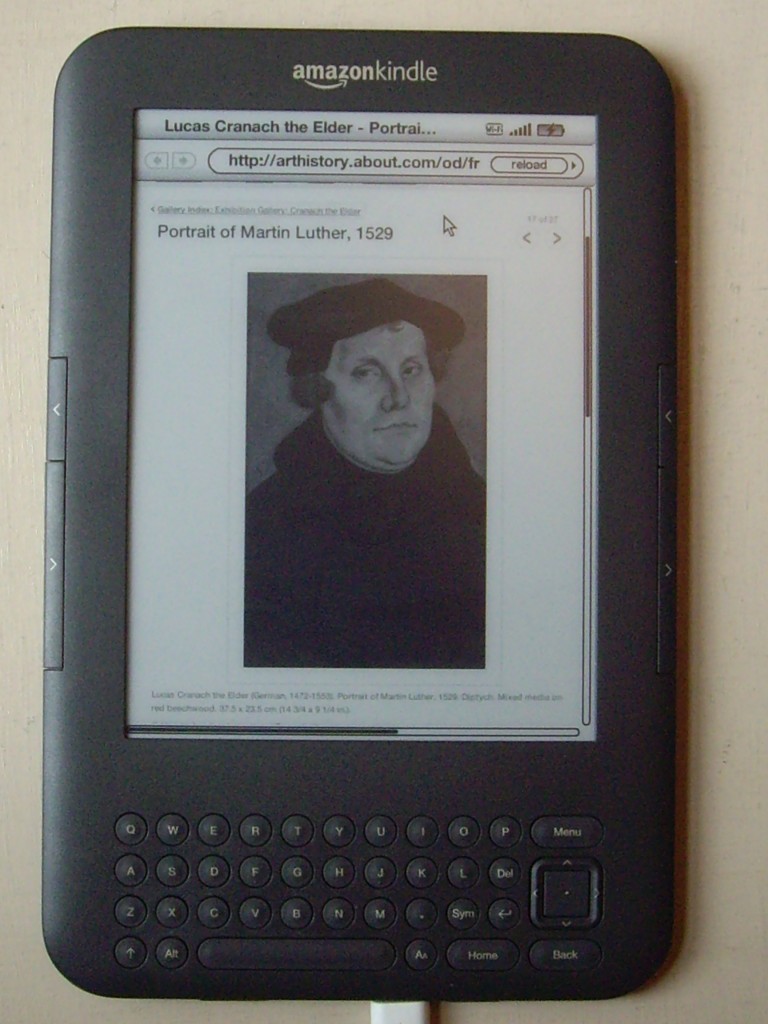

The bookmark is an element of codicological culture that has been borrowed by digital media and, particularly, the internet (a fact which, ironically, makes Google searching for articles on medieval bookmarks problematic). Nowadays, however, we are exhorted not just to ‘bookmark’ a webpage, but to ‘like’ it too. The once private reminder is being superseded by a public advertisement that disseminates a text through cyberspace (though to a degree ultimately dependent upon one’s privacy settings), and in a format and forum that then invites comment. Similarly, the Kindle e-reader allows e-books to be ‘e-annotated’: through ‘public notes’, marginalia can be shared and exchanged over the internet (though, again, this is limited by a Twitter-style system of ‘following’).

The hermetic life of a Carthusian did not perhaps encourage such discourse, but the frequent annotation in the margins of the manuscript above is suggestive of some level of intellectual exchange, however indirect then or untraceable now. The boundaries of that reading community were circumscribed physically by the cloister walls and materially by the movement of books within. Now, there are – potentially – no boundaries to reading communities. With the advent of e-readers, the anarcho-democratic ethos of the internet is now more closely tied to the book and to the text: freedom in the virtual margins, the power to broadcast, a limitless audience. The capacity of readers of e-books to not just record their thoughts but to disseminate them too may mean that much that was once private thought or evanescent orality is now cached and backed-up, and awaits future students of the ‘reading experience’. The ‘weightless text’ supports a heavier and heavier paratext of commentary, analysis and opinion, informed or not.

Where does authority lie in this digital world, this twenty-first-century Tower of Babel? How is authority constructed and maintained? Can the critic or academic maintain his status in a forum where comment is free – or should he or she even attempt to do so? In a recent article on the ‘patchy’ quality of the Coen brothers’ films, Will Self opined that ‘…the job of a serious cultural critic mostly consists in telling the generality of people that their opinions…simply aren’t up to scratch’. Ironically, the patchiness of Self’s own argument was quickly highlighted on the comments pages by some sharp-eyed readers, some of them no doubt the kind of ‘upper’ or ‘lower-middlebrow’ viewers whose opinions he had disdained so aristocratically. The article presents no critical engagement with specific interpretations or reviews except his own. In targeting ‘the generality’, does it do any more than represent Will Self’s self-will? And is that any more authoritative than the opinions he criticised?

Surely the job of the ‘serious cultural critic’ is to engage with and persuade, not just to tell – but then, perhaps, who is there to tell? The internet gathers together opinions so diverse and diffuse that it may be impossible to address them except in the most general terms. By transcending physical printed media, and by circumventing the complex and often slow publishing infrastructure through which debate has traditionally been channelled, the internet has removed nearly all ‘barriers to entry’ that once monitored or mediated the public sphere. In doing so, it has made available great opportunities for the advancement of knowledge through collaborative endeavour or adversarial dialectic. The internet has facilitated the freedom to comment, and has thus accentuated – though by no means created – a situation in which control over a text rests in no single pair of hands. That command over Scripture Martin Luther sought to reassert in his 1525 pamphlets Admonition to Peace and Against the Rioting Peasants. ‘Every man his own Bible reader’ he had once said, before the rise of heterodox interpretations of the vernacular holy text and the use of scriptural justification in the enactment of social revolution. How will these old issues of authority, interpretation and debate play out in the new age of ‘Every man his own Kindle reader’?

Surely the job of the ‘serious cultural critic’ is to engage with and persuade, not just to tell – but then, perhaps, who is there to tell? The internet gathers together opinions so diverse and diffuse that it may be impossible to address them except in the most general terms. By transcending physical printed media, and by circumventing the complex and often slow publishing infrastructure through which debate has traditionally been channelled, the internet has removed nearly all ‘barriers to entry’ that once monitored or mediated the public sphere. In doing so, it has made available great opportunities for the advancement of knowledge through collaborative endeavour or adversarial dialectic. The internet has facilitated the freedom to comment, and has thus accentuated – though by no means created – a situation in which control over a text rests in no single pair of hands. That command over Scripture Martin Luther sought to reassert in his 1525 pamphlets Admonition to Peace and Against the Rioting Peasants. ‘Every man his own Bible reader’ he had once said, before the rise of heterodox interpretations of the vernacular holy text and the use of scriptural justification in the enactment of social revolution. How will these old issues of authority, interpretation and debate play out in the new age of ‘Every man his own Kindle reader’?