A cat-obsessed friend just alerted me to the most creative piece of medieval marginalia I’ve ever seen. You can view it here.

Bizarre news the other day on BBC Radio 4’s The World at One (now available as a written feature on the BBC website). Verifiable figures are not available, but French firms – perhaps as many as 50% of them – continue to employ graphologists in recruitment processes. Applicants must submit a sample of their handwriting, which is then submitted to the ‘experts’ for analysis.

I don’t doubt that handwriting analysis can have specific practical or scholarly applications. I imagine the well-established techniques used by palaeographers to identify archaising scripts (or, conversely, to identify manuscripts copied by the same hand) – attention to the minute idiosyncrasies of letter formation and the duct of the scribes’ handwriting – aren’t too different to those involved in proving a modern forgery. Since such identifications can be the subject of scholarly disagreement, any ambitious claims for modern handwriting analysis need to be viewed with considerable scepticism.

Any attempt to apply graphology in the realms of psychology or medicine, however, just seems like bald charlatanism to me. Even where the stakes are far lower – in this case, occupational recruitment – I’m far from convinced of its usefulness. Like astrologers, chiromancers or psychics, graphologists stick to the vague and avoid the specific, and use evidence already given to them by the person they’re reading: literally, in this case, since graphologists usually study a handwritten personal statement rather than a neutral piece of writing and have spectacularly failed to give accurate descriptions when confronted with a neutral sample of handwriting.

The French attachment to graphology is a cultural one – they invented it, so it’s not surprising they remain attached to it – but it is used elsewhere, in Germany, Switzerland and Israel. Psychometric tests were, in their modern form, an American invention and remain more popular in the Anglophone world, though not to the exclusion of graphology. Indeed, graphology may be catching on on this side of La Manche. A growing number of companies justify its use as an additional screening tool because it is cheap and they claim it offers a fresh perspective on a candidate that CVs do not.

Could this perception that the manuscript word is more ‘personal’ than the printed or digital word – at a time when the future relationship between all three remains unclear – be a reaction against recruitment processes that have been rendered increasingly impersonal by e-mailed CVs and the use of online application systems? A 1990 report by the Law Society Gazette cautioned that – regardless of doubts about graphology’s credibility – European law states that submitted applications are the property of the recruiter. He or she may legally (though perhaps not ethically) send it for analysis without acquiring the applicant’s consent. So, when you’re next asked to provide something in manuscript – caveat scriptor! – you’ve no idea where it might end up.

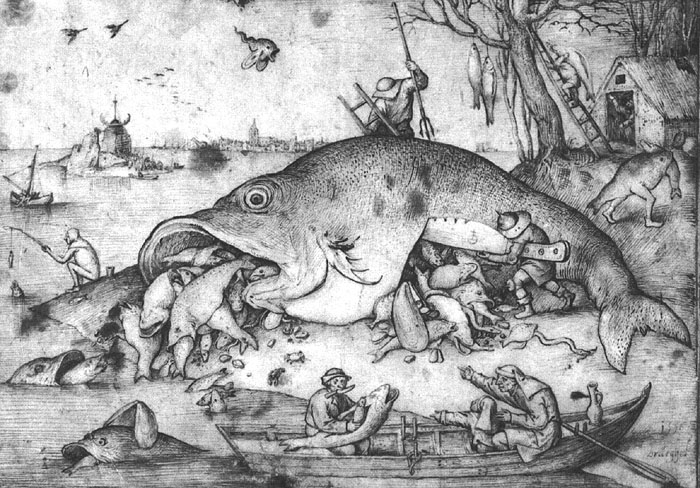

My last blogpost touched on the subject of trolling. Another diverting/infuriating form of digital textuality is the phishing email–the letter which tries to persuade you to give away all your numbers and passwords in order to spike your system, compromise your online security, or relieve you of significant sums of money. The etymologists link the word ‘phishing’, predictably enough, with fishing, angling for personal information (the OED dates its arrival to 1996), but explain that it has probably been crossed with ‘phreaking’–an older scam for getting free telephone calls (dating back to 1971).

My last blogpost touched on the subject of trolling. Another diverting/infuriating form of digital textuality is the phishing email–the letter which tries to persuade you to give away all your numbers and passwords in order to spike your system, compromise your online security, or relieve you of significant sums of money. The etymologists link the word ‘phishing’, predictably enough, with fishing, angling for personal information (the OED dates its arrival to 1996), but explain that it has probably been crossed with ‘phreaking’–an older scam for getting free telephone calls (dating back to 1971).

This morning members of the University of Cambridge were taken on a particularly creative phishing trip:

“Dear Staff/Student,

As phishing schemes become more sophisticated, with phishers being able to convince up to 50% of recipients to respond, it has become increasingly important for the Webmaster of The University of Cambridge to upgrade the University’s Webmail server to the new and more secured 2013 version.

This will enable your webmail take a new look, with virus protection and anti-spam Security. You are advised to verify and upgrade your account to the University’s 2013 latest Webmail version to enable recommended advanced features.

To verify your account, please click and follow the verification link below for the required upgrade or simply copy and paste the link into your web browser;

[link deleted, for obvious reasons]

To ensure full protection of your account, please take a few minutes now – it could save you a lot of time and frustration later.”

It’s ingenious, isn’t it? Shades of Shakespeare’s Iago, pretending that he wants to keep Othello from harm at the same time as he destroys his marriage and his mind. I particularly like ‘with phishers being able to convince up to 50% of recipients to respond’–such modesty!

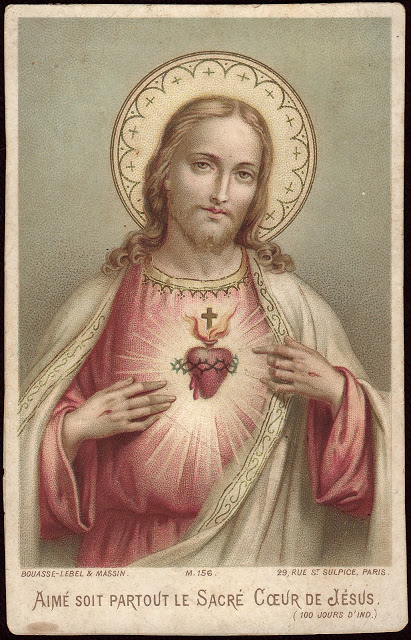

Robert Priest spoke at our seminar last night about his work on the fan mail and hate mail that arose from Ernest Renan’s Vie de Jésus (Life of Jesus, 1863). Treating the gospels as a set of unreliable historical sources rather than as Holy Writ, Renan’s study scandalized the Catholic establishment and became one of the most hotly-discussed and bestselling books of the age.

Robert Priest spoke at our seminar last night about his work on the fan mail and hate mail that arose from Ernest Renan’s Vie de Jésus (Life of Jesus, 1863). Treating the gospels as a set of unreliable historical sources rather than as Holy Writ, Renan’s study scandalized the Catholic establishment and became one of the most hotly-discussed and bestselling books of the age.

While the Vie received vast numbers of printed rebuttals, Renan himself was subjected to a torrent of letters from all over France and beyond its borders. Some of the letters were from readers who had experienced the book as a kind of revelation that brought the historical Jesus to life for the first time. But others were savagely hostile, calling the writer an animal and telling him that he would burn in hell for his lack of faith. A third type of communication came from those who sought to bring Renan back to the fold by gentler means, often with prayer cards depicting the Sacred Heart, significant terms underlined so as to drive home the message more directly. Taken together these letters testify to the extent to which the Vie (published in a cheap, simplified edition in  1864, and issued with illustrations in 1870) had penetrated French society, attracting readers among the rural poor as well as among urban elites. And they show how much controversy it continued to cause, while the author sat back and declined to comment on the furore.

1864, and issued with illustrations in 1870) had penetrated French society, attracting readers among the rural poor as well as among urban elites. And they show how much controversy it continued to cause, while the author sat back and declined to comment on the furore.

For the modern reader, these letters can’t but seem prescient of internet commentings, and of the virulent work of the troll, who employs the invisibility cloak of anonymity to post flagrantly offensive messages. (The recent trolling case involving Cambridge academic Mary Beard was widely publicized). But while anonymity was also a feature in much of Renan’s hate mail, Priest emphasized that these were not proto-posts. With no established line of communication, and no evidence of a concerted campaign of writing, each letter was the result of an individual initiative by the sender, an experiment pitting the power of handwriting against the force of print.