For some time I’ve been on the trail of an Elizabethan/Jacobean reader named William Neile. It all began when I read the discussion of Garnet’s straw in Julian Yates’ 2003 book Error Misuse Failure. Garnet’s straw was an ear of corn that fell out of a basket that was being used to dismember the body of the Jesuit priest Henry Garnet, just after he was executed for his alleged involvement in the Gunpowder Plot. Removed from the scene by a Catholic onlooker, the straw rapidly became a relic when it was found to bear ‘a perfect face, as if it had been painted, upon one of the husks’. It was encased in crystal and inevitably began to work miracles, which were (just as inevitably) debunked in a Protestant pamphlet entitled The Jesuits Miracles, or New Popish Wonders. Yates included a photograph of the title-page of this book, which has an amusing woodcut of the relic with its tiny face, in his discussion of the furore over Garnet’s posthumous agency. But the title-page of this particular copy (now in the British Library) also testified to a reader’s agency: it had, boldly inscribed beneath the title, the flourished signature of ‘Wm Neile’; further down the page on the right-hand side, the name ‘Jo Neile’.

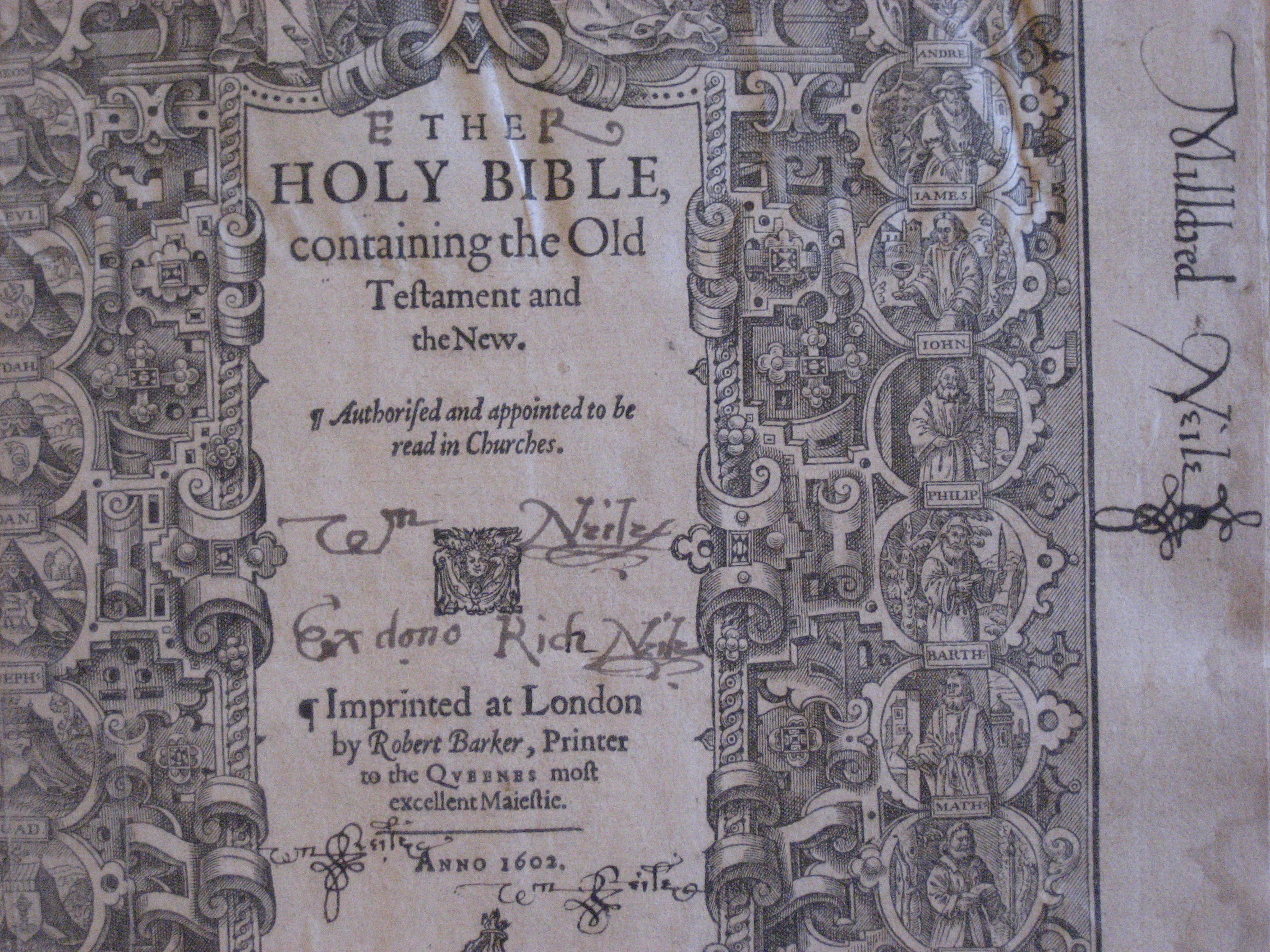

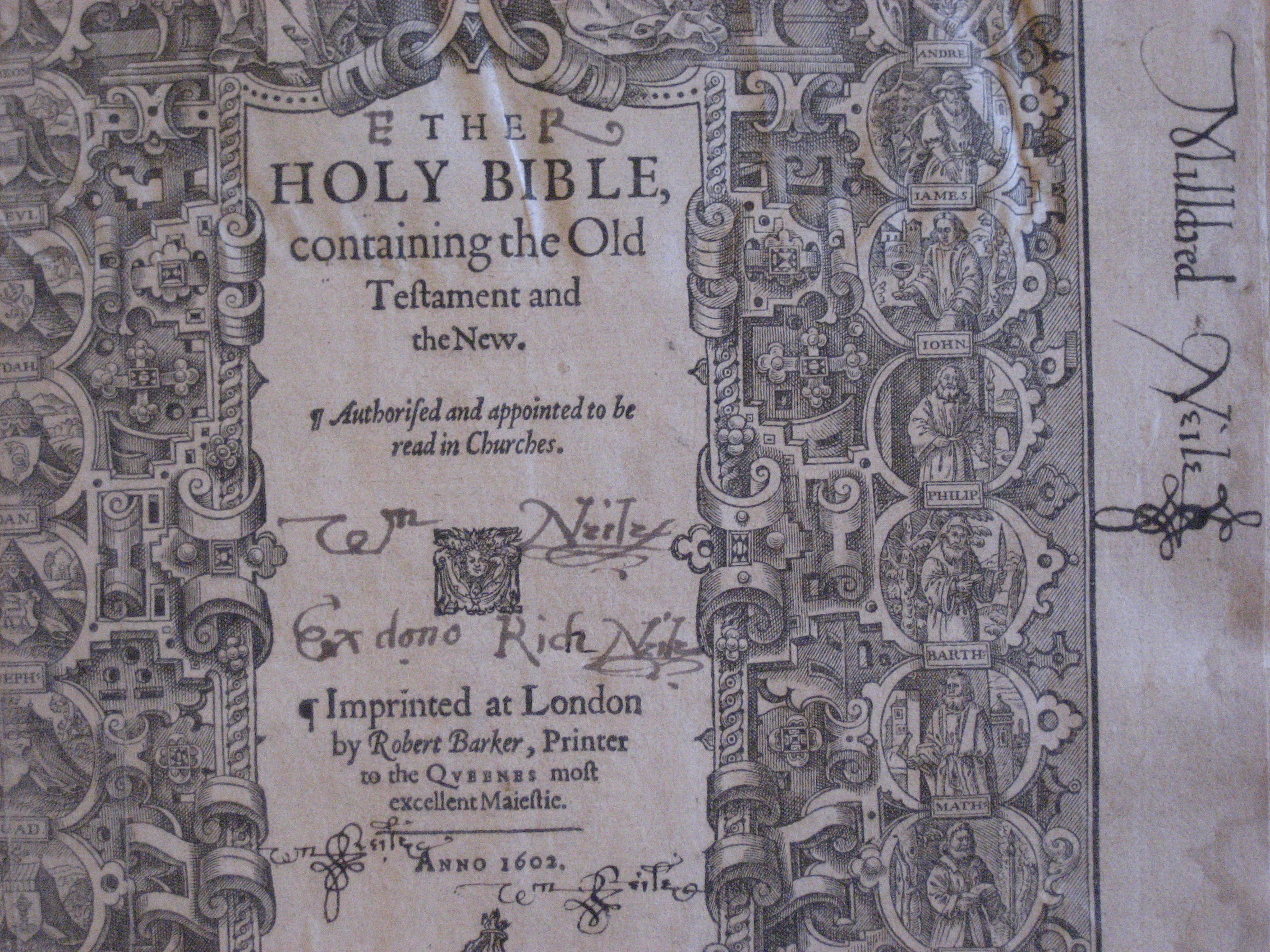

I’d seen that name before, and I would see it again, most prominently in a lavishly-bound 1602 Bible (possibly the former property of the dying Queen Elizabeth I) in the library of my own Cambridge college, Gonville and Caius. Here it was, again, involved in quite a showy performance–Neile signs his name three times, adds a note to the effect that the book was a gift from his brother Richard, and parades the name ‘Milldred Neile’ down the right-hand margin. I began to look out for Neile books, and to type the occasional idle provenance search into library catalogues that allow for such things.

I’d seen that name before, and I would see it again, most prominently in a lavishly-bound 1602 Bible (possibly the former property of the dying Queen Elizabeth I) in the library of my own Cambridge college, Gonville and Caius. Here it was, again, involved in quite a showy performance–Neile signs his name three times, adds a note to the effect that the book was a gift from his brother Richard, and parades the name ‘Milldred Neile’ down the right-hand margin. I began to look out for Neile books, and to type the occasional idle provenance search into library catalogues that allow for such things.

In the end I came up with a list of about 25 books, and it seemed to me to be an interesting list. There were plays–including John Day’s controversial The Ile of Guls, which ran into serious trouble for its attacks on the Scottish in the first years of the Stuart monarchy; a Jacobean masque, Middleton and Rowley’s The World Tost at Tennis, attacking extravagant clothing; and an old interlude called New Custom. There was page-turning romance (Barnabe Rich’s Don Simonides) and urban reportage (Thomas Dekker’s The Dead Terme). There was a helpful book to teach you how to boast like a Spaniard (Jacques Gaultier’s Rodomontados. Or, Bravadoes and bragardismes). There was religious literature–Latimer’s sermons, a life of Archbishop of Canterbury John Whitgift, more anti-Catholic polemic in various shapes and sizes. Above all, though, there was news, news about embassies to Spain, victories over the Turk, the villainies of the Catholic League, the coronation and later the burial of Henri IV. All of these titles showed signs of attentive reading, in the form of rapid pencil marks in the margins. The collection offered a scratch-portrait of a man-about-town, reading all kinds of things to keep himself informed, entertained and properly prejudiced. Here was a clear-cut case of what I call a ‘polyreader’, a reader on the lines of the poligrafi or ‘polywriters’ who wrote in many different modes to feed the hungry presses of Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Little more than a century after the arrival of print in England, here was the man that books built.

So who was this unknown reader? He was born in 1560, in the parish of St Margaret’s, Westminster, with which he would retain a lifelong association. In his early years, he appears to be have been a servant of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, the most powerful man in the land. He worked closely with his younger brother Richard, who was a household chaplain of Cecil’s at the start of a stellar career that took him from Dean of Westminster, via the  bishoprics of Rochester, Lichfield and Coventry, Lincoln, Durham, Winchester, to the Archbishopric of York. William seems to have spent the rest of his life clinging to Richard’s coat-tails, getting various posts in Westminster during his brother’s time there, and becoming his brother’s steward from 1612. He was himself ordained in 1616, and got a living at Sutton-in-the-Marsh, Lincolnshire; he died in 1624. After his death Richard went through William’s almanacs, stretching back to 1593, extracting notes on births, marriages, deaths, debts and freak weather, such as ‘A fearfull thunder one Crack lastinge neere halfe an hower’. (My thanks to Andrew Foster, who wrote the entry on Richard in the new DNB, for some of these biographical details).

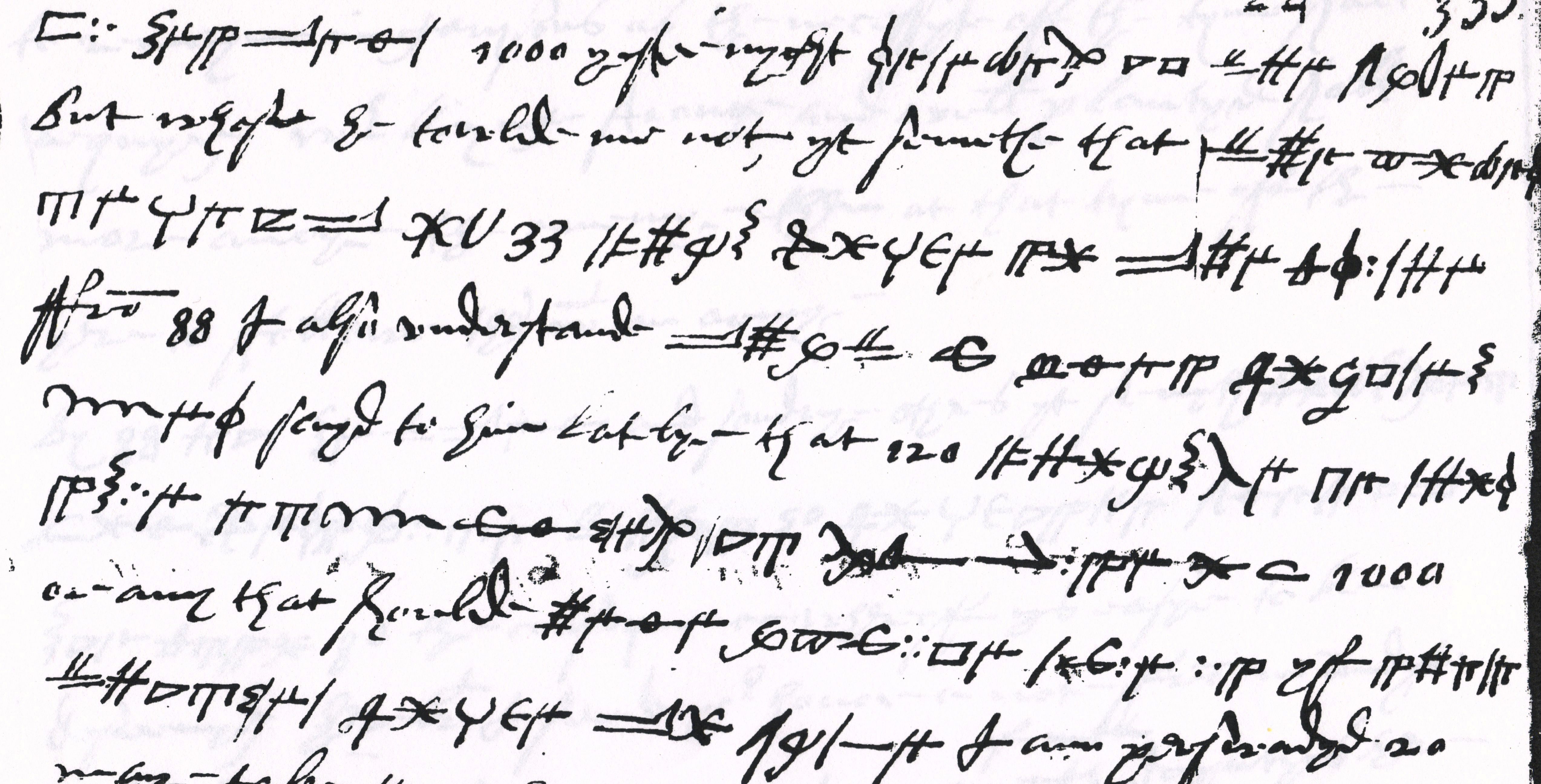

bishoprics of Rochester, Lichfield and Coventry, Lincoln, Durham, Winchester, to the Archbishopric of York. William seems to have spent the rest of his life clinging to Richard’s coat-tails, getting various posts in Westminster during his brother’s time there, and becoming his brother’s steward from 1612. He was himself ordained in 1616, and got a living at Sutton-in-the-Marsh, Lincolnshire; he died in 1624. After his death Richard went through William’s almanacs, stretching back to 1593, extracting notes on births, marriages, deaths, debts and freak weather, such as ‘A fearfull thunder one Crack lastinge neere halfe an hower’. (My thanks to Andrew Foster, who wrote the entry on Richard in the new DNB, for some of these biographical details).

Last week I finally got my hands on Will’s will, which turns out to be quite a document. The principal bequests are to his children, who are given various bizarre/delightful combinations of weapons and armour, musical instruments, chests and boxes, and money. (In a later codicil William laments the fact that he seems to have spent all the money, so the gifts have to be scaled down somewhat). But above all, he gives books, and in the process he puts my modest reconstruction of his reading in perspective. To Mildred, his eldest daughter, he gives 100 books. To Richard, his eldest son, he gives 200. Then William and John also get 200 each, while Dorothy and Frances have to make do with just 40 apiece; but newborn Robert, since he’s male, gets 100. Each of the books has, the will informs us, been individually assigned with the name of the recipient written on the title-page–as we saw with the 1602 Bible (for Mildred) and Garnet’s straw (for John), above.

So there is some work to be done here. I have about 25 books, but it would be nice to locate the remaining 855. If you find one, let me know (jes1003@cam.ac.uk)!