I first learnt the name of William Herle thanks to this website–I posted an image of an illegible signature I’d found a sixteenth-century book and got a response (from Arnold Hunt at the BL) telling me that it was Herle’s. Then I came across the online edition of Herle’s letters, created by Robyn Adams, Alison Wiggins and their team at the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters. And then I started to get interested in Herle himself, as a couple of vivid letters took me into the Elizabethan underworld, which turned out also to be a literary underworld, a place where people forged books as readily as they forged coins.

Herle was an intelligencer–a news-gatherer and secret agent–working for Elizabeth’s spymasters William Cecil, Lord Burghley and Francis Walsingham. His main area of expertise was the Low Countries, which he visited on several occasions, sometimes on his own, sometimes with official delegations (accompanying the duke of Alençon in 1582, following the earl of Leicester’s army in 1585). Despite his evident value to the authorities, he spent much of his life in crippling debt, and his letters mingle their nuggets of ‘intelligence’ with petitions for financial support. But, as David Lewis Jones puts it in the new DNB, ‘his many requests for a permanent position were ignored by his powerful friends and this suggests that they considered him useful but not entirely trustworthy’. Such was the allotted destiny of a double-agent who hung around with the dodgiest of characters in order to keep Elizabeth’s brutal regime on the tracks.

While we have a mine of information about Herle’s activities from the 1560s through to his death in 1588/9, we have no idea when he was born, and know nothing about his early life, save that he was born in the Welsh Marches, the son of Thomas Herle of Montgomery. He seems to have kept up his ties to the borders (an illegitimate daughter was baptized at Guilsfield, near Welshpool, in 1576). We also know that, somewhere along the way, he acquired many tongues. DNB says that ‘he was well educated with a good knowledge of languages, including Latin, Flemish, and Italian, and probably also French and Spanish’.

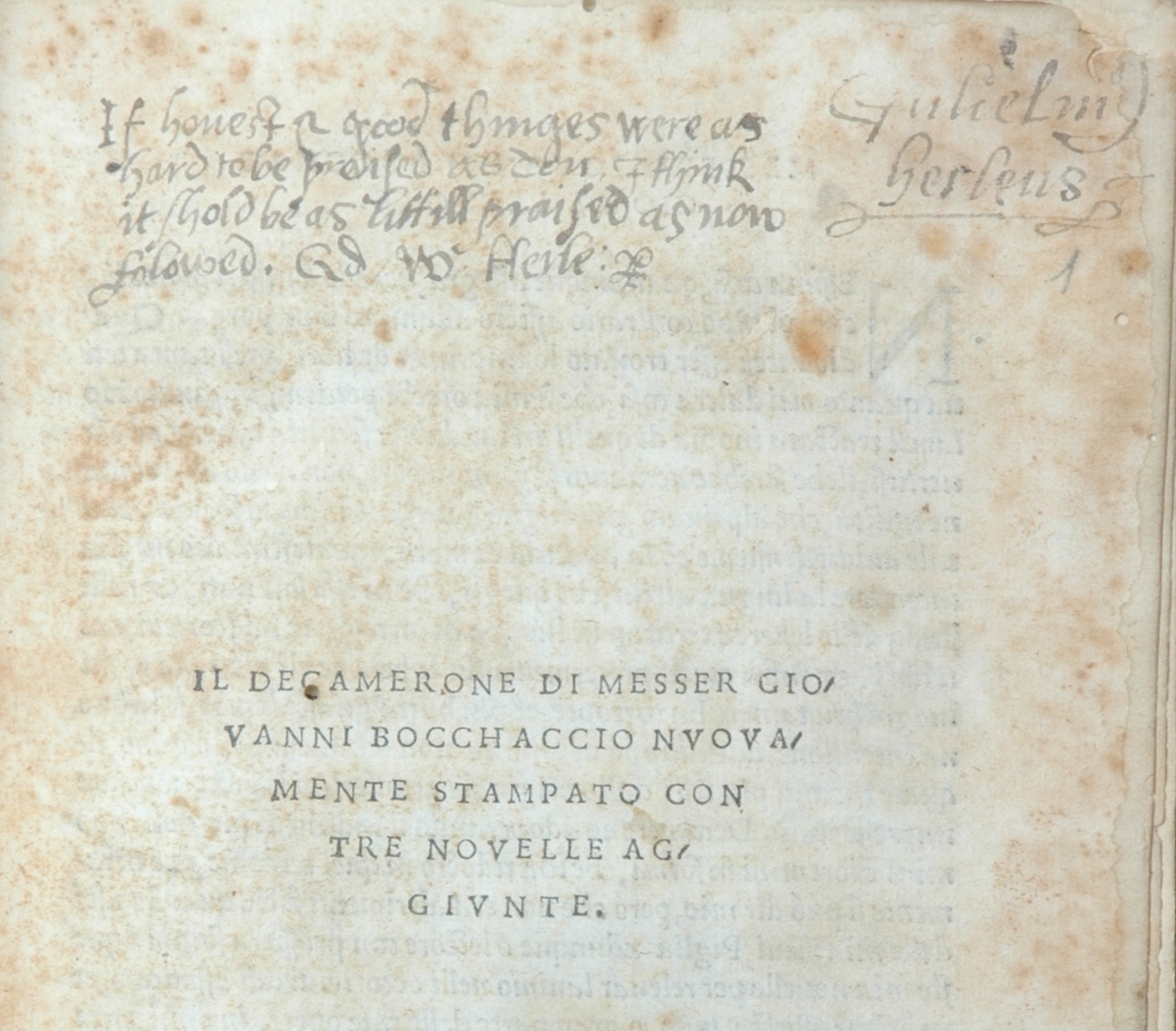

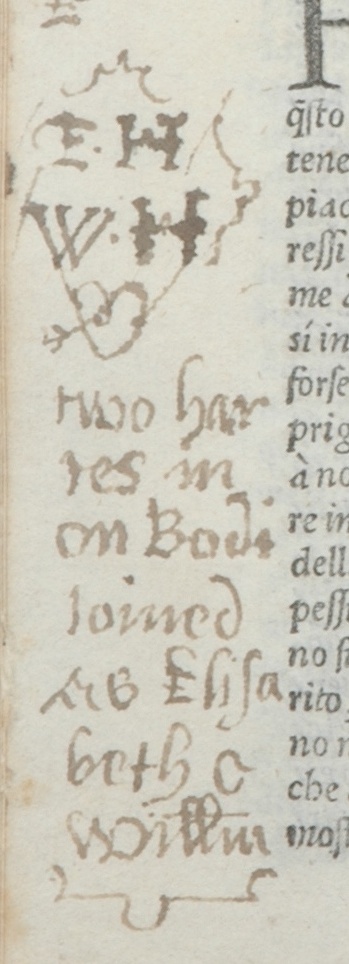

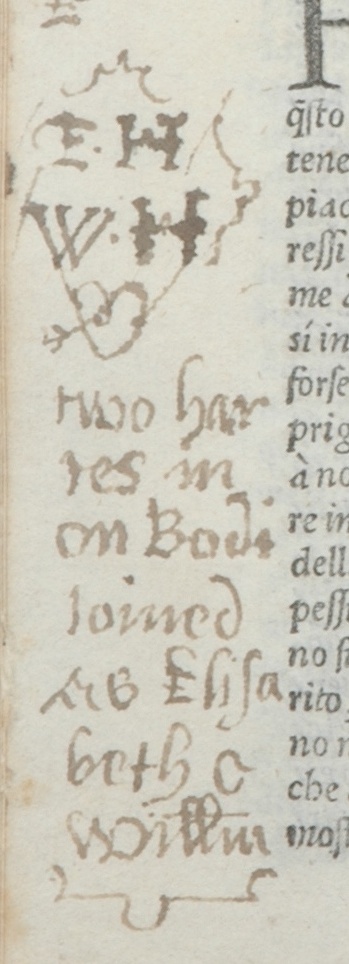

Recently a book has surfaced that might shed some light on Herle’s language-learning, and thanks to the generosity of its current owner I’ve had the privilege of spending some time poring over it. It’s a copy of Boccaccio’s Decameron, in the edition printed by Filippo Giunta in Florence in 1516. The title-page is signed ‘Guilielm[us] herleus’, alongside a cynical epigraph: ‘If honest & good thinges were as hard to be preised as don, I think it [sic] shold be as littill praised as now folowed. Q[uo]d W. Herle.’ The book bears various other Herle signatures, no two of which are alike. And strikingly, offsetting the cynicism, there are also a couple of lovey-dovey marginal inscriptions in which Herle celebrates his relationship with an ‘Elizabeth’. ‘E.H. / W.H. / two hearts in one Body joined as Elisabeth & William’, runs one of them. Who the lady was, we don’t know (there is no evidence that Herle ever married).

Recently a book has surfaced that might shed some light on Herle’s language-learning, and thanks to the generosity of its current owner I’ve had the privilege of spending some time poring over it. It’s a copy of Boccaccio’s Decameron, in the edition printed by Filippo Giunta in Florence in 1516. The title-page is signed ‘Guilielm[us] herleus’, alongside a cynical epigraph: ‘If honest & good thinges were as hard to be preised as don, I think it [sic] shold be as littill praised as now folowed. Q[uo]d W. Herle.’ The book bears various other Herle signatures, no two of which are alike. And strikingly, offsetting the cynicism, there are also a couple of lovey-dovey marginal inscriptions in which Herle celebrates his relationship with an ‘Elizabeth’. ‘E.H. / W.H. / two hearts in one Body joined as Elisabeth & William’, runs one of them. Who the lady was, we don’t know (there is no evidence that Herle ever married).

Besides these signatures, the book contains quite a serious  scattering of notes to the text, the majority of which are in Italian. Some analyse the structure of the stories or pick out striking details (the number of people killed by the 1348 plague that provides the spur for the narrative cycle; the ladies’ claim that ‘men are women’s leaders’; a proverb dropped by a crafty abbot, ‘peccato celato mezo perdonato’–‘a sin hidden is half forgiven’; or a range of bogus relics including the finger of the Holy Spirit and the forelock of a seraph). Other bits of marginalia note particular words and phrases (‘paliscalmo’, a little boat; ‘muratore’, bricklayer; ‘inimicheuol tempo’, a terrible time). Some of these may have been penned by other readers, possibly Italian readers–with such tiny samples it’s hard to say how many annotators were involved. But a few of the notes are in English, or they translate Italian terms into English–as when ‘sopra la stangha’ is glossed (correctly, it seems) as ‘a perche for a ha[w]ke’. And one of the tales–a charming narrative which sets out to prove part of the wisdom of Solomon to the effect that women need to be beaten to be kept in line–is marked (in English) ‘to be tra[n]slatyd’. This strongly suggests some kind of language-learning context, in which translation exercises are being set for the students.

scattering of notes to the text, the majority of which are in Italian. Some analyse the structure of the stories or pick out striking details (the number of people killed by the 1348 plague that provides the spur for the narrative cycle; the ladies’ claim that ‘men are women’s leaders’; a proverb dropped by a crafty abbot, ‘peccato celato mezo perdonato’–‘a sin hidden is half forgiven’; or a range of bogus relics including the finger of the Holy Spirit and the forelock of a seraph). Other bits of marginalia note particular words and phrases (‘paliscalmo’, a little boat; ‘muratore’, bricklayer; ‘inimicheuol tempo’, a terrible time). Some of these may have been penned by other readers, possibly Italian readers–with such tiny samples it’s hard to say how many annotators were involved. But a few of the notes are in English, or they translate Italian terms into English–as when ‘sopra la stangha’ is glossed (correctly, it seems) as ‘a perche for a ha[w]ke’. And one of the tales–a charming narrative which sets out to prove part of the wisdom of Solomon to the effect that women need to be beaten to be kept in line–is marked (in English) ‘to be tra[n]slatyd’. This strongly suggests some kind of language-learning context, in which translation exercises are being set for the students.

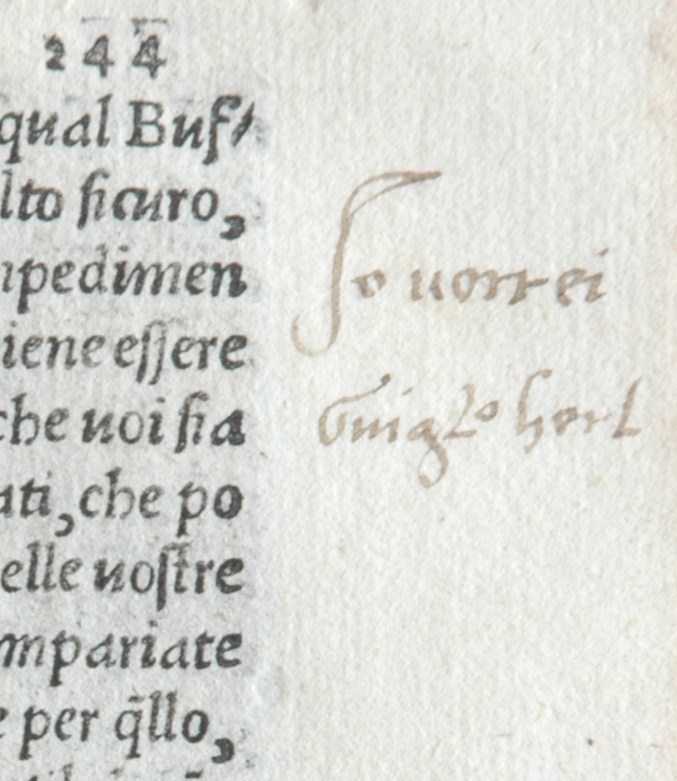

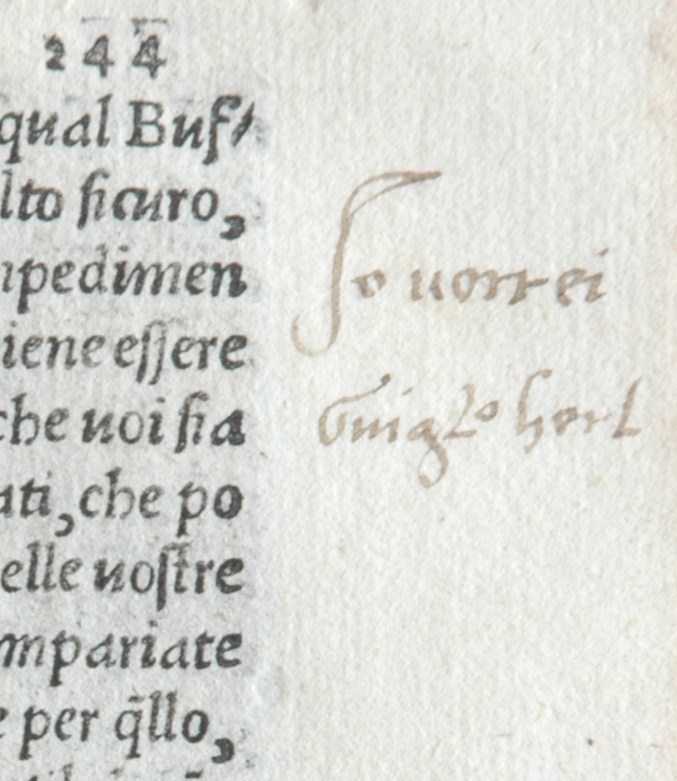

Perhaps the most delicious feature of the book is that it lets you see Herle in the process of turning Italian. In one of the margins, apropos of nothing in the text, he writes in tiny, precise letters: ‘Io vorrei [I would like] / Giugl[ielm]o herl’. Having already Latinized himself on the title-page, Herle here turns his nam e into an Italian equivalent, and produces it in an unusual hand that looks as if it might itself be aspiring to southern European elegance.

e into an Italian equivalent, and produces it in an unusual hand that looks as if it might itself be aspiring to southern European elegance.

Although they have some features in common, it’s not easy to match the writing in these notes with the later writing of the spy William Herle. But then there is a bewildering variety of styles on display even in his signatures–suggesting this is an identity under construction, playing with different hands and tongues (the perfect training for a spy?) It can only be an educated guess, but my strong suspicion is that these notes are indeed evidence for the early life of the intelligencer. More guesses: it’s the 1540s, we’re in a schoolroom, somewhere in Italy, and Herle is immersing himself in one of the greatest of storytellers.

[Thanks to Guyda Armstrong and Elisabeth Leedham-Green for discussing aspects of this book with me. An exhibition commemorating the 700th anniversary of Boccaccio’s birth is currently taking place at the John Rylands Library, University of Manchester].

A postscript: this book has now been purchased by the Cambridge University Library, and can be called up in the Rare Books Room: classmark 5000.c.73

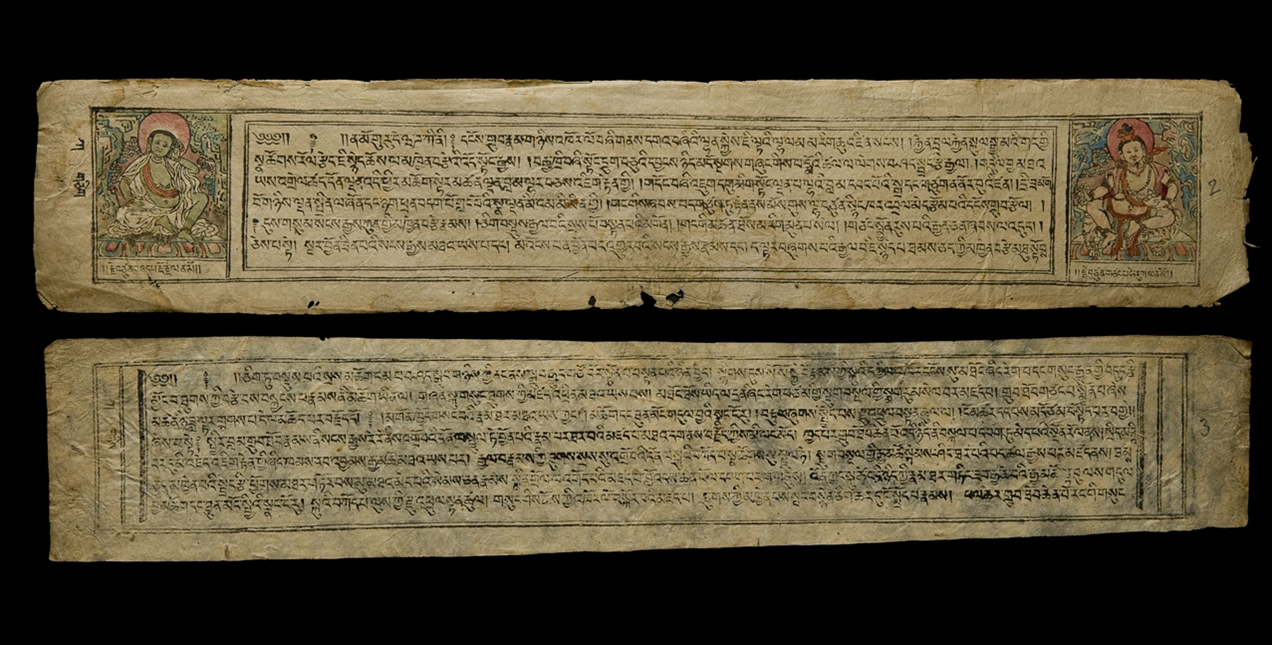

Have just spent a fascinating couple of days at a conference on ‘Printing as an Agent of Change in Tibet and Beyond’, a spin-off from the project on ‘Transforming Technologies and Buddhist Book Culture’ based in the Department of Social Anthropology in Cambridge. It’s been really exciting to see how the picture of Tibetan printing, stretching back to the 12th century, is being pieced together with great patience and smartness by a very devoted community of academics.

Have just spent a fascinating couple of days at a conference on ‘Printing as an Agent of Change in Tibet and Beyond’, a spin-off from the project on ‘Transforming Technologies and Buddhist Book Culture’ based in the Department of Social Anthropology in Cambridge. It’s been really exciting to see how the picture of Tibetan printing, stretching back to the 12th century, is being pieced together with great patience and smartness by a very devoted community of academics. with the material evidence, going right down to the fibres of the plants that were used to make the paper (which can be analysed by peering down the microscope, but also by conducting fieldwork with papermakers and by gathering local knowledge). And let’s not forget the wood that made the boards (which the dendrochronologists in Arizona want to be able to date thanks to the tree-ring evidence) or the pigments that went into decorating it (which can be analysed by UV reflectance spectography by a band based in the Fitzwilliam Museum who normally concentrate on Western illuminated manuscripts). Each of these subjects of microscopic analysis is also dauntingly macroscopic, since you can only make sense of the data when you have mapped both the local ecosystem and Tibet’s trade links with the wider world. It’s truly pioneering work, and as an added bonus it’s usually accompanied by breathtaking images of life on the roof of the planet.

with the material evidence, going right down to the fibres of the plants that were used to make the paper (which can be analysed by peering down the microscope, but also by conducting fieldwork with papermakers and by gathering local knowledge). And let’s not forget the wood that made the boards (which the dendrochronologists in Arizona want to be able to date thanks to the tree-ring evidence) or the pigments that went into decorating it (which can be analysed by UV reflectance spectography by a band based in the Fitzwilliam Museum who normally concentrate on Western illuminated manuscripts). Each of these subjects of microscopic analysis is also dauntingly macroscopic, since you can only make sense of the data when you have mapped both the local ecosystem and Tibet’s trade links with the wider world. It’s truly pioneering work, and as an added bonus it’s usually accompanied by breathtaking images of life on the roof of the planet.