Have just spent a fascinating couple of days at a conference on ‘Printing as an Agent of Change in Tibet and Beyond’, a spin-off from the project on ‘Transforming Technologies and Buddhist Book Culture’ based in the Department of Social Anthropology in Cambridge. It’s been really exciting to see how the picture of Tibetan printing, stretching back to the 12th century, is being pieced together with great patience and smartness by a very devoted community of academics.

Have just spent a fascinating couple of days at a conference on ‘Printing as an Agent of Change in Tibet and Beyond’, a spin-off from the project on ‘Transforming Technologies and Buddhist Book Culture’ based in the Department of Social Anthropology in Cambridge. It’s been really exciting to see how the picture of Tibetan printing, stretching back to the 12th century, is being pieced together with great patience and smartness by a very devoted community of academics.

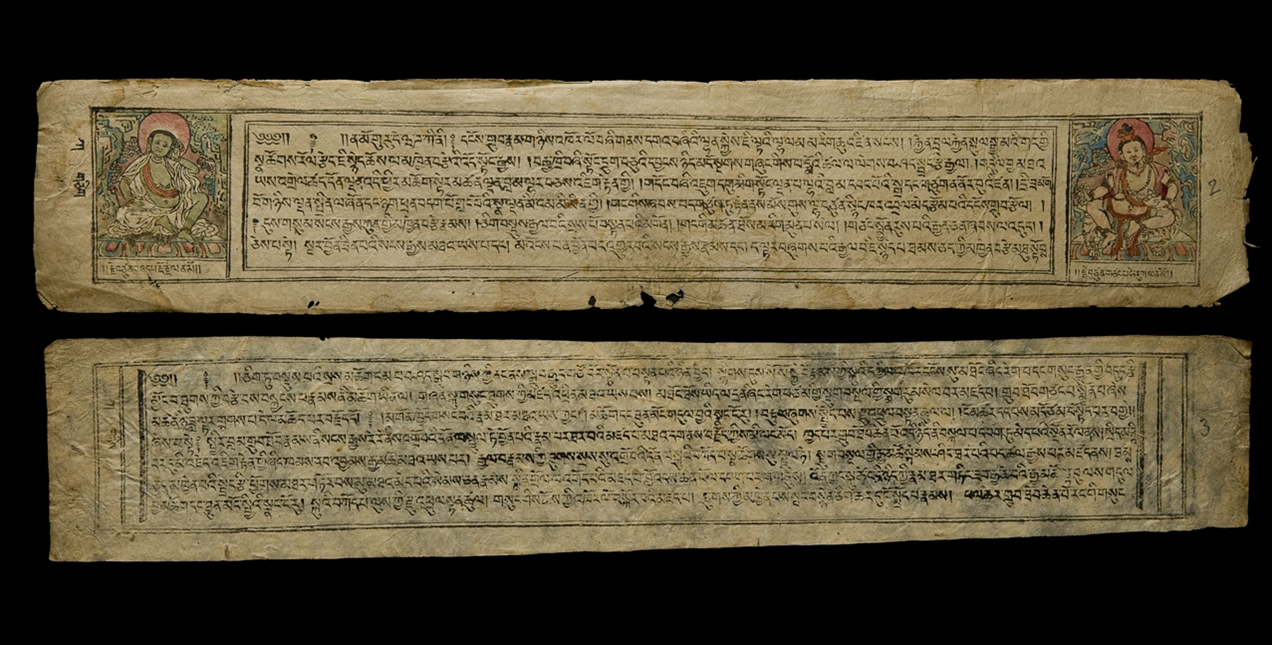

Part of the jigsaw is the cultural analysis–what sort of texts were being circulated, and what were the relationships between those texts and the patrons who funded the costly business of woodblock printing, often as a form of spiritual ‘merit-making’? But at the same time there are the nuts-and-bolts questions about exactly what was being printed and where, the basic assembly of a corpus. (Large quantities of relevant evidence are still making nests for birds and food for rats in obscure buildings across the country). Thankfully, Tibetan texts seem usually to come with colophons, which offer information about the various agents who were involved in the particular printing project. Then there’s the mapping of print, and particularly of the apparent explosion of print in the fifteenth century–where were the printing houses, and why? Then there are the big questions about the difference that printing made, and how that relates to its impact elsewhere in the world.

The Tibetanists turn out to be doing amazing things  with the material evidence, going right down to the fibres of the plants that were used to make the paper (which can be analysed by peering down the microscope, but also by conducting fieldwork with papermakers and by gathering local knowledge). And let’s not forget the wood that made the boards (which the dendrochronologists in Arizona want to be able to date thanks to the tree-ring evidence) or the pigments that went into decorating it (which can be analysed by UV reflectance spectography by a band based in the Fitzwilliam Museum who normally concentrate on Western illuminated manuscripts). Each of these subjects of microscopic analysis is also dauntingly macroscopic, since you can only make sense of the data when you have mapped both the local ecosystem and Tibet’s trade links with the wider world. It’s truly pioneering work, and as an added bonus it’s usually accompanied by breathtaking images of life on the roof of the planet.

with the material evidence, going right down to the fibres of the plants that were used to make the paper (which can be analysed by peering down the microscope, but also by conducting fieldwork with papermakers and by gathering local knowledge). And let’s not forget the wood that made the boards (which the dendrochronologists in Arizona want to be able to date thanks to the tree-ring evidence) or the pigments that went into decorating it (which can be analysed by UV reflectance spectography by a band based in the Fitzwilliam Museum who normally concentrate on Western illuminated manuscripts). Each of these subjects of microscopic analysis is also dauntingly macroscopic, since you can only make sense of the data when you have mapped both the local ecosystem and Tibet’s trade links with the wider world. It’s truly pioneering work, and as an added bonus it’s usually accompanied by breathtaking images of life on the roof of the planet.