Early sea pilots’ books were “books you kept on the bridge of your ship”, according to T.A. Birrell. He writes in his 1986 Panizzi Lectures on English Monarchs and their Books that one of the most intact surviving examples of the genre was owned by Prince Henry, most likely because it was never taken on board to be “soaked with the rain and the spray”. The Prince’s copy of Pierre Garcie’s Le Grand Routier (1607, Rouen) probably owes its acquisition to the navigator Edward Wright, who was the prince’s mathematics tutor and later librarian.

Le Grand Routier was just one in a series of “sea rutters” whose origins can be found in early fifteenth-century manuscripts. ‘Rutter’ was the English name for a book of sailing directions, derived from the French routier, route-book. The equivalent expression in Portuguese was roteiro; in Spanish derrota; in Italian portalano (port-book); in Dutch leeskaart (reading chart); in German, Seebuch (sea-book). Although Portuguese manuscript roteiros existed in the early fifteenth century, they were treated as top-secret documents, and it is likely that the first printed book of sailing directions, an Italian portalano published in Venice by Bernadino Rizo in 1490 derived from a compilation of French manuscript route-books. One example of an early manuscript rutter, copied between 1461 and 1465 by the scribe William Ebesham, survives in BL MS Lansdowne 285, a manuscript better known as Sir John Paston’s “grete booke”.

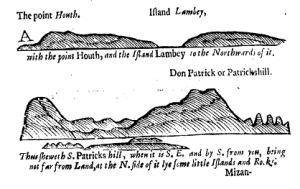

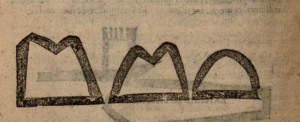

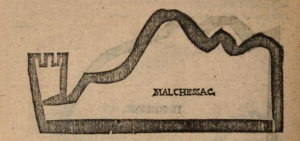

The route-book written by Pierre Garcie (1430?-1503?), which was later reprinted in the edition owned by Prince Henry, was the first to focus on the physical features of the coast, comprehensively describing the appearance of the coasts and the sea-bed of western France, Spain, and Portugal. Most importantly, Garcie illustrated his route-book with 59 woodcuts, made by Enguilbert  de Marnef, which gave seamen an impression of coastal outlines. Birrell describes each woodcut as “a heavy, crude, black silhouette: you stared at the printed page and imprinted the silhouette on your visual memory, and then looked up from the book, into the rain and the fog, trying to find a coastal outline that would fit”.

de Marnef, which gave seamen an impression of coastal outlines. Birrell describes each woodcut as “a heavy, crude, black silhouette: you stared at the printed page and imprinted the silhouette on your visual memory, and then looked up from the book, into the rain and the fog, trying to find a coastal outline that would fit”.

These woodcuts were made as early as 1484, but did not change significantly until the seventeenth century. Their crudeness did not detract from their imitation of important coastal features which the seaman in unfamiliar waters could recognise even through miserable weather. As D.W. Waters writes in The Rutters of the Sea (1962), the woodcuts “made prominent with simplicity what the anxious shipmaster sought”, when he perceived a coast “looming up suddenly over a darkening sea, or frowning over spume-swept waters through the gloom of leaden skies”.

These woodcuts were made as early as 1484, but did not change significantly until the seventeenth century. Their crudeness did not detract from their imitation of important coastal features which the seaman in unfamiliar waters could recognise even through miserable weather. As D.W. Waters writes in The Rutters of the Sea (1962), the woodcuts “made prominent with simplicity what the anxious shipmaster sought”, when he perceived a coast “looming up suddenly over a darkening sea, or frowning over spume-swept waters through the gloom of leaden skies”.

By the later seventeenth century, printed rutters had established finer detail in illustrating coasts, though their use on board, as reference volumes with illustrations to be compared and held up to unfamiliar coastal views, remained the same. Few printed rutters survive, so Prince Henry’s well-preserved 1607 copy of Le Grand Routier is worth a browse; it has been digitised on Google Books here.