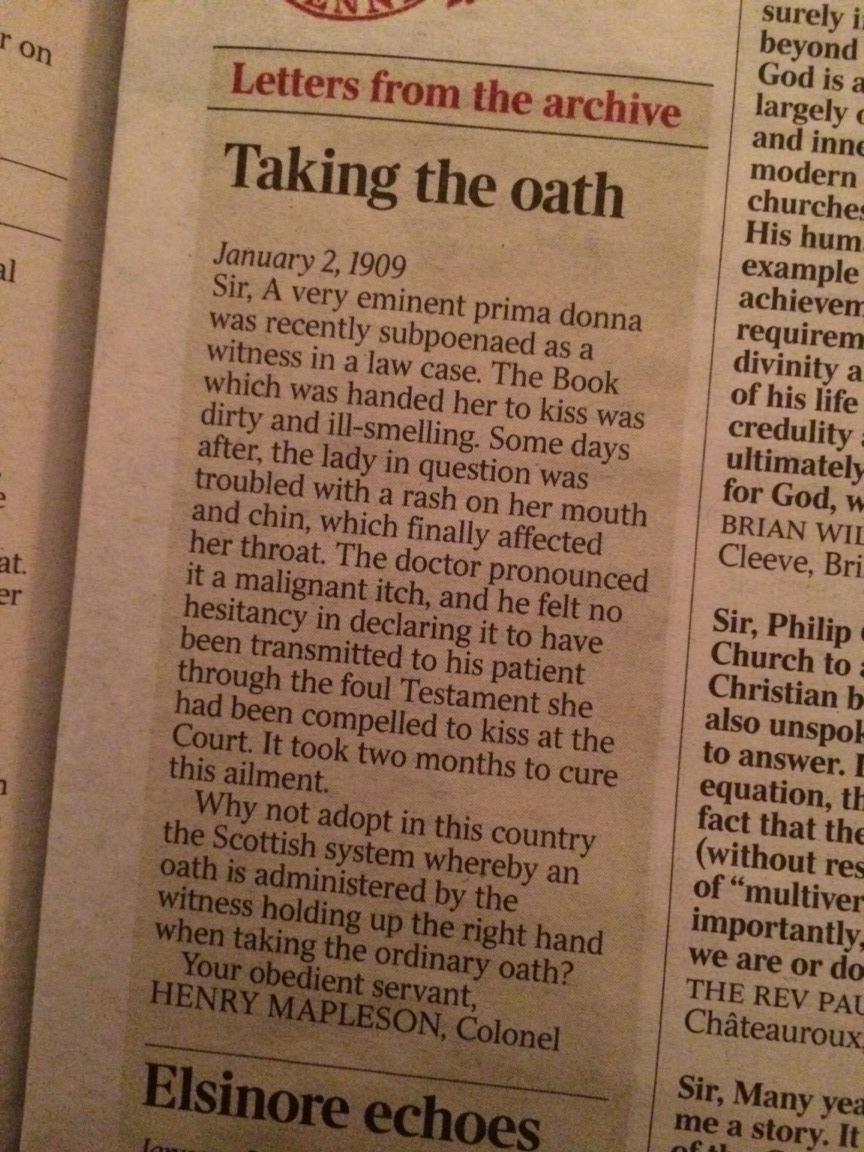

One of the broadsheets found in their archive this sorry story of a witness in a law case and the ‘foul Testament’ from which she contracted a ‘malignant itch’ after kissing it by way of swearing her oath. While a certain ’eminent prima donna’ of our own times has met with other troubles after her recent appearance as a witness in a high-profile trial, she has at least avoided this troublesome complaint. The original correspondent would be pleased to know that kissing the Book is no longer necessary in Court…

One of the broadsheets found in their archive this sorry story of a witness in a law case and the ‘foul Testament’ from which she contracted a ‘malignant itch’ after kissing it by way of swearing her oath. While a certain ’eminent prima donna’ of our own times has met with other troubles after her recent appearance as a witness in a high-profile trial, she has at least avoided this troublesome complaint. The original correspondent would be pleased to know that kissing the Book is no longer necessary in Court…

and meanwhile a couple of wags at the New York Times have come up with a witty prescription for the rebranding of print… Happy new year!

A colleague sent me a link to a slightly creepy article in the New York Times in which (as he neatly put it) ‘GCHQ meets CMT’. It seems that it’s not just governments and social media outfits that are intent on spying on us. It’s also publishers, who thanks to the burgeoning of ebooks are pioneering new ways of knowing what we read and how we respond to it.

There are all sorts of ways in which such information might be used, but the article seems to be most excited about the possibility of taking a focus-group approach to creative writing. Just as a big-budget movie might be tested out on an audience to find ways of increasing its appeal prior to general release, so novelists will now be able to find out what their readers like and ‘give them more of it’. I recoil in horror from the whole idea, but doubtless it will help someone somewhere to make a fast buck…

The one-day workshop on ‘The Biblioteca Hernandina and the Early Modern Book World’, held at the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge on Tuesday, was a richly stimulating event. Organised by Edward Wilson-Lee and José María Pérez Fernández, the workshop convened a group of experts to discuss aspects of the enormous library of Hernando Colón, son of Christopher Columbus, who after some early journeying with his father in the New World devoted much of his life to travelling in search of books.

The one-day workshop on ‘The Biblioteca Hernandina and the Early Modern Book World’, held at the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge on Tuesday, was a richly stimulating event. Organised by Edward Wilson-Lee and José María Pérez Fernández, the workshop convened a group of experts to discuss aspects of the enormous library of Hernando Colón, son of Christopher Columbus, who after some early journeying with his father in the New World devoted much of his life to travelling in search of books.

José María and Edward kicked things off by offering a potted biography of Colón and an account of his life in book-buying. His shopping expeditions began in Spain in 1510, moved on to Italy in 1512, and subsequently took him to Germany, France, the Netherlands and England. He also sent agents out to extend his collections, instructing them to focus on cheaper and more unusual small-format books rather than buying the kind of expensive folios that could be obtained anywhere. Along the way he paid visits to heroes such as Erasmus, taking care to receive at least one book as a gift on each visit, and he may have befriended Albrecht Durer, whose works he added to his vast collection of printed woodcuts and engravings. The result was a library that dwarfed other collections of the day, boasting more than 15,000 titles. A number of catalogues witness his struggle not merely to list the books he owned, but also to render them useful. Rather than letting the books die on the shelves, he sought to release their contents through a massive project of indexing and epitomizing–a project that was doomed to failure, and which was left unfinished at his death in 1539.

One of the most striking features of Hernando’s collecting was his enthusiasm for ephemera, and in the morning session Miguel Martínez explored his penchant for broadside ballads, newsbooks and controversial pamphlets–the sort of cheap publications that would have flooded the streets of his native Seville. Despite their former ubiquity, such items now survive in single copies if they survive at all, and they no longer extant in Cólon’s library as it survives in Seville Cathedral. Andrew Pettegree picked up this topic of lost books, suggesting that as many as two-thirds of all early modern editions may have disappeared without trace. He explained how the editors of the Universal Short Title Catalogue are using a variety of archival records to infer the existence of lost editions–10,000 of them so far–which are being added to the catalogue to create a much fuller map of pre-1600 print culture. The third paper in this session focused on a particular book, Christopher Columbus’s copy of Marco Polo’s account of China. Ana Carolina Hosne reconsidered the question of how far Columbus was aware of Polo’s work when he set out to pioneer a westward route to Cathay–given that his copy in the Biblioteca Hernandina post-dates his second expedition of 1498.

The afternoon session began with Tess Knighton on Cólon’s music books. As well as setting Cólon in relation to other Spanish collectors, Knighton’s talk challenged the idea that all of Cólon’s music-buying would have required foreign travel. Although it is clear that some of his shopping for the earliest printed polyphonic music was done in Italy, the mobility of books in the period was such that a range of international publications would have been on sale in Seville. Alexander Marr took on the subject of prints, exploring the curious blind-spots in Cólon’s massive collection of woodcut and intaglio images and asking whether these point us to his personal tastes, or merely to the financial constraints imposed by someone who seems to have watched every maravedí as he trawled the seas of ink. Vittoria Feola concluded the session by considering the fate of the Hernandina library in relation to other great collections, including the library of Elias Ashmole, which she is currently cataloguing. Her account of the unpredictable twists and turns of books-as-property suggested that there are many ways in which a library can be ‘lost’. The most perfectly preserved collection can be unknown and unused, kept in a gilded cage with no catalogue to guide readers to its contents.

The conference closed with a round-table discussion which started out from a fascinating memoir of Cólon by his servant Juan Pérez, and which moved on to attempt to integrate the day’s findings. Was Cólon a bad collector, someone who put quantity above quality and whose cataloguing techniques were little better than quixotic? What should we make of his buying of books in languages he couldn’t read and that he considered ‘barbaric’ (such as his large collection of German Lutheran pamphlets)? And what sense can we make of his ephemeral collecting? Does his investment in the popular mark him out as exceptional, or does our propensity to find it surprising merely reveal the distortions in our view of the period?

You can read more about the project, and see some photos from books in Cólon’s collections, here.

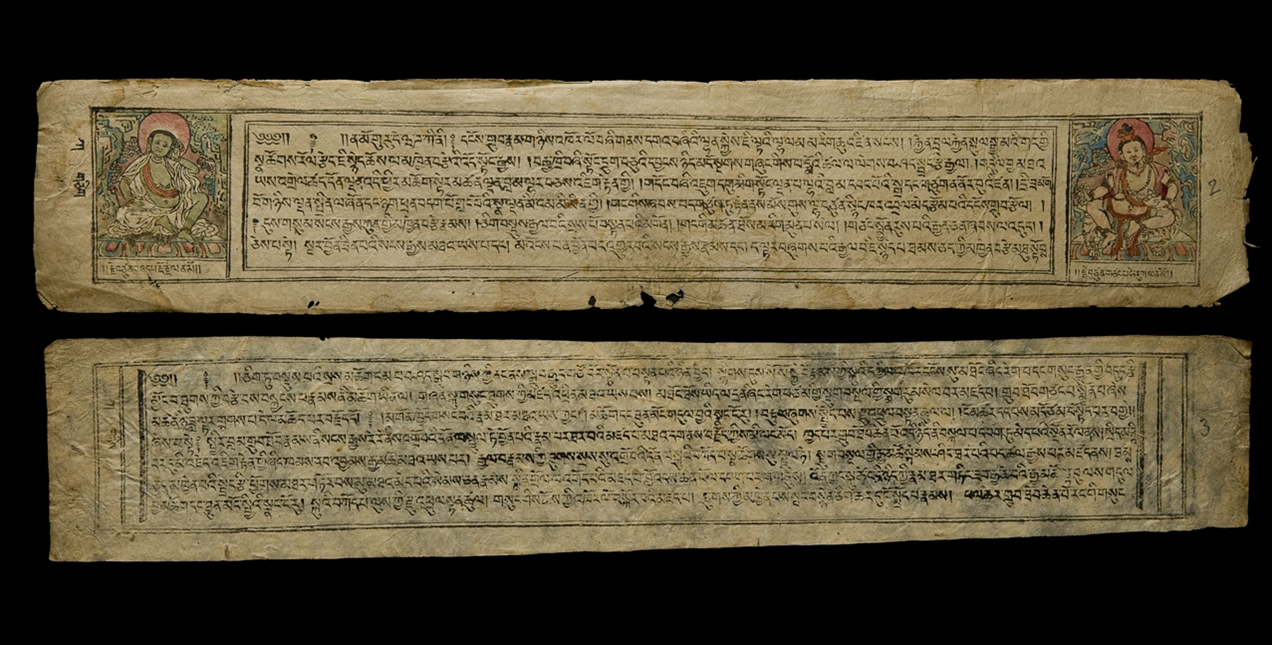

Have just spent a fascinating couple of days at a conference on ‘Printing as an Agent of Change in Tibet and Beyond’, a spin-off from the project on ‘Transforming Technologies and Buddhist Book Culture’ based in the Department of Social Anthropology in Cambridge. It’s been really exciting to see how the picture of Tibetan printing, stretching back to the 12th century, is being pieced together with great patience and smartness by a very devoted community of academics.

Have just spent a fascinating couple of days at a conference on ‘Printing as an Agent of Change in Tibet and Beyond’, a spin-off from the project on ‘Transforming Technologies and Buddhist Book Culture’ based in the Department of Social Anthropology in Cambridge. It’s been really exciting to see how the picture of Tibetan printing, stretching back to the 12th century, is being pieced together with great patience and smartness by a very devoted community of academics.

Part of the jigsaw is the cultural analysis–what sort of texts were being circulated, and what were the relationships between those texts and the patrons who funded the costly business of woodblock printing, often as a form of spiritual ‘merit-making’? But at the same time there are the nuts-and-bolts questions about exactly what was being printed and where, the basic assembly of a corpus. (Large quantities of relevant evidence are still making nests for birds and food for rats in obscure buildings across the country). Thankfully, Tibetan texts seem usually to come with colophons, which offer information about the various agents who were involved in the particular printing project. Then there’s the mapping of print, and particularly of the apparent explosion of print in the fifteenth century–where were the printing houses, and why? Then there are the big questions about the difference that printing made, and how that relates to its impact elsewhere in the world.

The Tibetanists turn out to be doing amazing things  with the material evidence, going right down to the fibres of the plants that were used to make the paper (which can be analysed by peering down the microscope, but also by conducting fieldwork with papermakers and by gathering local knowledge). And let’s not forget the wood that made the boards (which the dendrochronologists in Arizona want to be able to date thanks to the tree-ring evidence) or the pigments that went into decorating it (which can be analysed by UV reflectance spectography by a band based in the Fitzwilliam Museum who normally concentrate on Western illuminated manuscripts). Each of these subjects of microscopic analysis is also dauntingly macroscopic, since you can only make sense of the data when you have mapped both the local ecosystem and Tibet’s trade links with the wider world. It’s truly pioneering work, and as an added bonus it’s usually accompanied by breathtaking images of life on the roof of the planet.

with the material evidence, going right down to the fibres of the plants that were used to make the paper (which can be analysed by peering down the microscope, but also by conducting fieldwork with papermakers and by gathering local knowledge). And let’s not forget the wood that made the boards (which the dendrochronologists in Arizona want to be able to date thanks to the tree-ring evidence) or the pigments that went into decorating it (which can be analysed by UV reflectance spectography by a band based in the Fitzwilliam Museum who normally concentrate on Western illuminated manuscripts). Each of these subjects of microscopic analysis is also dauntingly macroscopic, since you can only make sense of the data when you have mapped both the local ecosystem and Tibet’s trade links with the wider world. It’s truly pioneering work, and as an added bonus it’s usually accompanied by breathtaking images of life on the roof of the planet.

Tomorrow I’m heading off to the new Library of Birmingham for a conference entitled ‘Resurrecting the Book‘. When I tell people this, they tend to ask: ‘Is it dead?’ I could point them to a letter sent home my son’s school last week, which read:

“Dear Parent / Carer of Year 8,

We are delighted to inform you that your child has been loaned a copy of A Christmas Carol, which they will be studying in English until the end of the Autumn term. Students will be bringing their copy home to enable them to continue reading and enjoying the novel outside of lessons. We ask that you join us in encouraging students to look after their copy as it will be passed on to other students in the future.

Each copy has been marked with a unique code, which will enable us to keep track of the books. Your child is responsible for returning their copy of A Christmas Carol, at the end of term, by the 19th December 2013. Any books which are not returned will need to be replaced at a cost of £4.99. Please note this is specifically a charge for books that are not returned and not a general charge for borrowing the text.

We look forward to enjoying reading the novel alongside year 8 in the coming weeks.”

I’m sure that a year or two ago the act of borrowing a book from school would have been an everyday affair, completely taken for granted. Now it needs a detailed explanation and a fanfare of celebration. Soon each book will have to come with an instruction manual, and (probably) a charger.

I first learnt the name of William Herle thanks to this website–I posted an image of an illegible signature I’d found a sixteenth-century book and got a response (from Arnold Hunt at the BL) telling me that it was Herle’s. Then I came across the online edition of Herle’s letters, created by Robyn Adams, Alison Wiggins and their team at the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters. And then I started to get interested in Herle himself, as a couple of vivid letters took me into the Elizabethan underworld, which turned out also to be a literary underworld, a place where people forged books as readily as they forged coins.

Herle was an intelligencer–a news-gatherer and secret agent–working for Elizabeth’s spymasters William Cecil, Lord Burghley and Francis Walsingham. His main area of expertise was the Low Countries, which he visited on several occasions, sometimes on his own, sometimes with official delegations (accompanying the duke of Alençon in 1582, following the earl of Leicester’s army in 1585). Despite his evident value to the authorities, he spent much of his life in crippling debt, and his letters mingle their nuggets of ‘intelligence’ with petitions for financial support. But, as David Lewis Jones puts it in the new DNB, ‘his many requests for a permanent position were ignored by his powerful friends and this suggests that they considered him useful but not entirely trustworthy’. Such was the allotted destiny of a double-agent who hung around with the dodgiest of characters in order to keep Elizabeth’s brutal regime on the tracks.

While we have a mine of information about Herle’s activities from the 1560s through to his death in 1588/9, we have no idea when he was born, and know nothing about his early life, save that he was born in the Welsh Marches, the son of Thomas Herle of Montgomery. He seems to have kept up his ties to the borders (an illegitimate daughter was baptized at Guilsfield, near Welshpool, in 1576). We also know that, somewhere along the way, he acquired many tongues. DNB says that ‘he was well educated with a good knowledge of languages, including Latin, Flemish, and Italian, and probably also French and Spanish’.

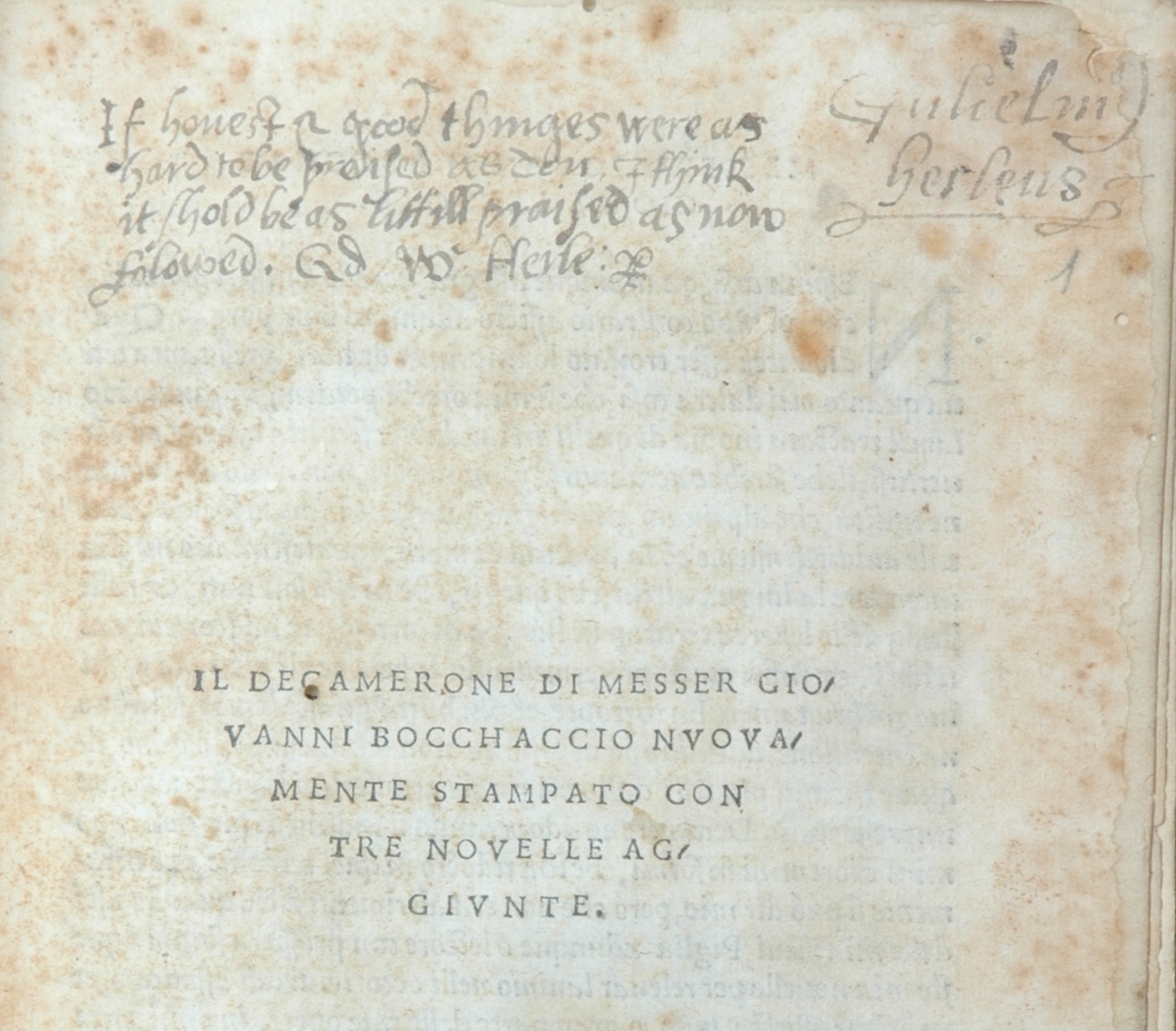

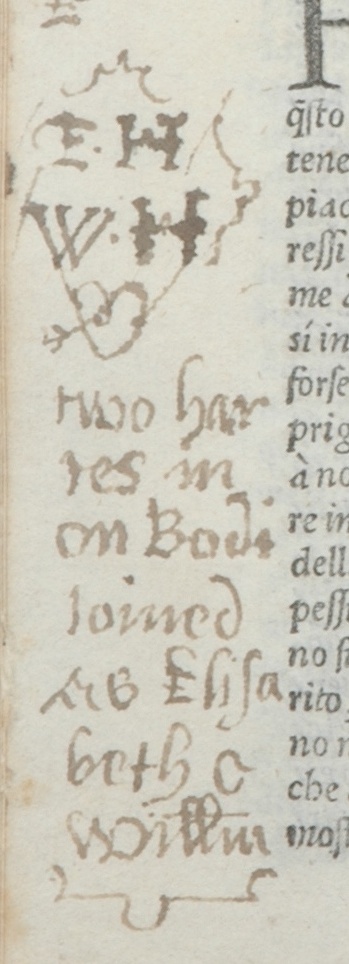

Recently a book has surfaced that might shed some light on Herle’s language-learning, and thanks to the generosity of its current owner I’ve had the privilege of spending some time poring over it. It’s a copy of Boccaccio’s Decameron, in the edition printed by Filippo Giunta in Florence in 1516. The title-page is signed ‘Guilielm[us] herleus’, alongside a cynical epigraph: ‘If honest & good thinges were as hard to be preised as don, I think it [sic] shold be as littill praised as now folowed. Q[uo]d W. Herle.’ The book bears various other Herle signatures, no two of which are alike. And strikingly, offsetting the cynicism, there are also a couple of lovey-dovey marginal inscriptions in which Herle celebrates his relationship with an ‘Elizabeth’. ‘E.H. / W.H. / two hearts in one Body joined as Elisabeth & William’, runs one of them. Who the lady was, we don’t know (there is no evidence that Herle ever married).

Recently a book has surfaced that might shed some light on Herle’s language-learning, and thanks to the generosity of its current owner I’ve had the privilege of spending some time poring over it. It’s a copy of Boccaccio’s Decameron, in the edition printed by Filippo Giunta in Florence in 1516. The title-page is signed ‘Guilielm[us] herleus’, alongside a cynical epigraph: ‘If honest & good thinges were as hard to be preised as don, I think it [sic] shold be as littill praised as now folowed. Q[uo]d W. Herle.’ The book bears various other Herle signatures, no two of which are alike. And strikingly, offsetting the cynicism, there are also a couple of lovey-dovey marginal inscriptions in which Herle celebrates his relationship with an ‘Elizabeth’. ‘E.H. / W.H. / two hearts in one Body joined as Elisabeth & William’, runs one of them. Who the lady was, we don’t know (there is no evidence that Herle ever married).

Besides these signatures, the book contains quite a serious  scattering of notes to the text, the majority of which are in Italian. Some analyse the structure of the stories or pick out striking details (the number of people killed by the 1348 plague that provides the spur for the narrative cycle; the ladies’ claim that ‘men are women’s leaders’; a proverb dropped by a crafty abbot, ‘peccato celato mezo perdonato’–‘a sin hidden is half forgiven’; or a range of bogus relics including the finger of the Holy Spirit and the forelock of a seraph). Other bits of marginalia note particular words and phrases (‘paliscalmo’, a little boat; ‘muratore’, bricklayer; ‘inimicheuol tempo’, a terrible time). Some of these may have been penned by other readers, possibly Italian readers–with such tiny samples it’s hard to say how many annotators were involved. But a few of the notes are in English, or they translate Italian terms into English–as when ‘sopra la stangha’ is glossed (correctly, it seems) as ‘a perche for a ha[w]ke’. And one of the tales–a charming narrative which sets out to prove part of the wisdom of Solomon to the effect that women need to be beaten to be kept in line–is marked (in English) ‘to be tra[n]slatyd’. This strongly suggests some kind of language-learning context, in which translation exercises are being set for the students.

scattering of notes to the text, the majority of which are in Italian. Some analyse the structure of the stories or pick out striking details (the number of people killed by the 1348 plague that provides the spur for the narrative cycle; the ladies’ claim that ‘men are women’s leaders’; a proverb dropped by a crafty abbot, ‘peccato celato mezo perdonato’–‘a sin hidden is half forgiven’; or a range of bogus relics including the finger of the Holy Spirit and the forelock of a seraph). Other bits of marginalia note particular words and phrases (‘paliscalmo’, a little boat; ‘muratore’, bricklayer; ‘inimicheuol tempo’, a terrible time). Some of these may have been penned by other readers, possibly Italian readers–with such tiny samples it’s hard to say how many annotators were involved. But a few of the notes are in English, or they translate Italian terms into English–as when ‘sopra la stangha’ is glossed (correctly, it seems) as ‘a perche for a ha[w]ke’. And one of the tales–a charming narrative which sets out to prove part of the wisdom of Solomon to the effect that women need to be beaten to be kept in line–is marked (in English) ‘to be tra[n]slatyd’. This strongly suggests some kind of language-learning context, in which translation exercises are being set for the students.

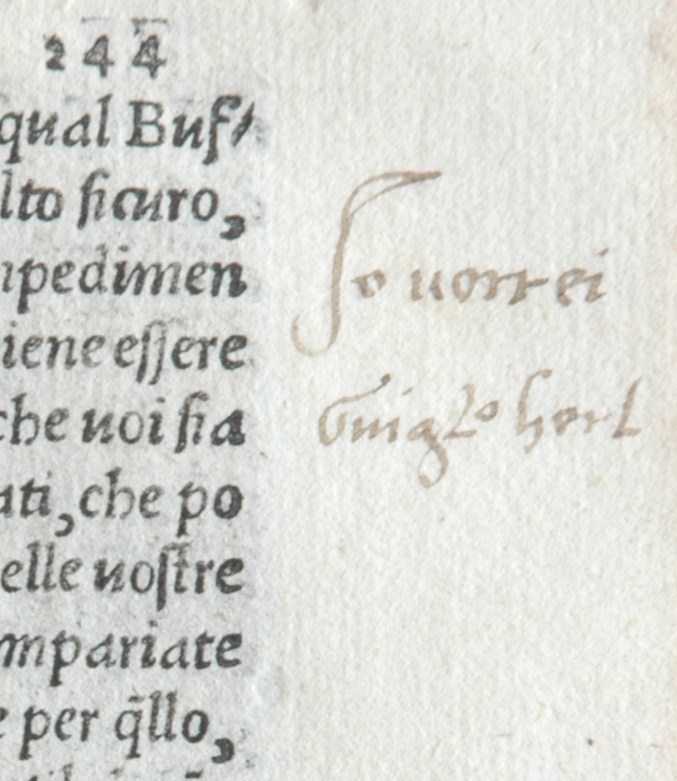

Perhaps the most delicious feature of the book is that it lets you see Herle in the process of turning Italian. In one of the margins, apropos of nothing in the text, he writes in tiny, precise letters: ‘Io vorrei [I would like] / Giugl[ielm]o herl’. Having already Latinized himself on the title-page, Herle here turns his nam e into an Italian equivalent, and produces it in an unusual hand that looks as if it might itself be aspiring to southern European elegance.

e into an Italian equivalent, and produces it in an unusual hand that looks as if it might itself be aspiring to southern European elegance.

Although they have some features in common, it’s not easy to match the writing in these notes with the later writing of the spy William Herle. But then there is a bewildering variety of styles on display even in his signatures–suggesting this is an identity under construction, playing with different hands and tongues (the perfect training for a spy?) It can only be an educated guess, but my strong suspicion is that these notes are indeed evidence for the early life of the intelligencer. More guesses: it’s the 1540s, we’re in a schoolroom, somewhere in Italy, and Herle is immersing himself in one of the greatest of storytellers.

[Thanks to Guyda Armstrong and Elisabeth Leedham-Green for discussing aspects of this book with me. An exhibition commemorating the 700th anniversary of Boccaccio’s birth is currently taking place at the John Rylands Library, University of Manchester].

A postscript: this book has now been purchased by the Cambridge University Library, and can be called up in the Rare Books Room: classmark 5000.c.73

In all of the media reporting of the trial and conviction of Marine A for the murder of an ‘insurgent’ in Afghanistan in 2011, surprisingly little has been said about the conspicuously literary reference that accompanied the fatal gunshot. ‘There you are, shuffle off this mortal coil, you cunt. It’s nothing you wouldn’t do to us’.

In all of the media reporting of the trial and conviction of Marine A for the murder of an ‘insurgent’ in Afghanistan in 2011, surprisingly little has been said about the conspicuously literary reference that accompanied the fatal gunshot. ‘There you are, shuffle off this mortal coil, you cunt. It’s nothing you wouldn’t do to us’.

The quotation comes from one of the most enigmatic moments in Hamlet (and the whole of English literature?), right in the thick of the ‘To be or not to be’ speech, when the prince of Denmark is at his most ruminative. To be or not to be? Death is deeply desirable, a ‘consummation / Devoutly to be wished’. But if death is a sleep, it is a sleep that may be disturbed by dreams. And ‘there’s the rub, / For in that sleep of death what dreams may come / When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, / Must give us pause’. (For ‘mortal coil’, the RSC edition glosses: ‘bustle or turmoil of this mortal life’). And so, Hamlet concludes, we carry on bearing the pains of life because we fear greater pains after death. That is the reason why he is not going to commit suicide, or to undertake what he construes as a suicide mission to revenge the murder of his father upon his uncle.

The soliloquy is about the avoidance of action, and is itself a way of avoiding action, of spinning out words rather than deeds. Avoiding action turns out also to mean avoiding plain speech. Those ‘dreams’ that Hamlet talks of, the ‘something after death’ which ‘conscience’ fears, probably mean the fires of Hell (his father’s ghost, after all, is sizzling in Purgatory). But hellfire cannot be named directly. Part of the weirdness of Marine A’s quotation is that he co-opts the circumlocutions and avoidances of Hamlet’s speech for a purpose which is terrifyingly direct, the execution of his revenge. The eruption of the literary may, however, be linked to the fact that Marine A was himself spinning fictions about the physical condition of the enemy fighter. A couple of minutes earlier, he radioed to a colleague using a comparable euphemism: ‘I hate to say it, administering first aid to this er- individual, he’s er … passed on from the world, over’.

A bit of me wants to ask whether Shakespeare has ever been turned to such savage ends, but you only have to think of Titus Andronicus to realise that the field of modern warfare overlaps substantially with the world of Shakespearean drama. Meanwhile the London Review of Books recently reported that medical staff in Guantánamo Bay have taken Shakespearean names to make it harder to report them for misconduct. The doctors who are being encouraged to flout the rules of the 1975 Tokyo Declaration, which forbids the force-feeding of hunger-strikers, are now called Leonato, Varro, Cordelia, Cressida, Helena, Silius, Valeria, Lucentio and Lucio. Again, there’s some kind of grim appropriateness to this institutionalized insanity.

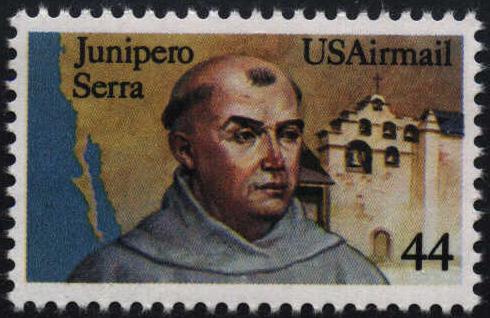

I learnt a lot from another current exhibition at the Huntington, about the man sometimes called the ‘founding father of California’. ‘Junipero Serra and the Legacies of the California Missions’ coincides with the 300th anniversary of the birth of the Franciscan priest who journeyed in the mid-1700s from the Spanish island of Mallorca to Mexico, and then up to California, where he established a series of missions for the conversion of the native Indians to the Catholic faith.

Curated by Steven Hackel and Catherine Gudis, this tremendous exhibition paints a very complex picture of the relationships between the region’s diverse Indian communities and the Franciscans who ran the missions throughout the eighteenth century and beyond.

Many of the 250+ artefacts (from the Huntington’s collections, and loaned from an impressive number of other places as well) in the exhibition were intriguing material texts – some of the numerous letters Serra wrote to fellow priests in Mexico, and to his family back in Spain; a woodblock supposedly used by Serra to print religious sheets for distribution in the streets; rare surviving written examples of a few of the more than one hundred languages spoken by the Indian communities. One of the really striking things was the bureaucratic efficiency of the Franciscans in charge of the missions, who documented every baptism, marriage, and burial. As the curators are careful to point out, these records would have been for Serra and his colleagues a glorious accounting of souls saved, but they can also be read as a terrible toll of mission life on Californian communities: disease, for example, brought untimely death to thousands of Indians. The surviving records have been collated in the Early California Population Project.

All Californian schoolchildren learn about Junipero Serra today, and this remarkable exhibition attempts to complicate some of the traditional narratives around this figure, emphasising the rich range of responses of the Indians to the missionaries. The curators also stress the ways in which both the Indian and Spanish pasts have been romanticised – through the ‘mission revival’ architectural fashions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the evolution of the missions into tourist attractions, for example. Another material text chosen for the exhibition speaks of this tendency to mythologise California’s complex past: in 1967, Ronald Reagan was sworn into office as Governor of the state with a bible thought (though nobody can be sure) to have been used by Serra.

The exhibition continues until 6th January 2014, and is definitely worth a visit if you’re in the area.

For some time I’ve been on the trail of an Elizabethan/Jacobean reader named William Neile. It all began when I read the discussion of Garnet’s straw in Julian Yates’ 2003 book Error Misuse Failure. Garnet’s straw was an ear of corn that fell out of a basket that was being used to dismember the body of the Jesuit priest Henry Garnet, just after he was executed for his alleged involvement in the Gunpowder Plot. Removed from the scene by a Catholic onlooker, the straw rapidly became a relic when it was found to bear ‘a perfect face, as if it had been painted, upon one of the husks’. It was encased in crystal and inevitably began to work miracles, which were (just as inevitably) debunked in a Protestant pamphlet entitled The Jesuits Miracles, or New Popish Wonders. Yates included a photograph of the title-page of this book, which has an amusing woodcut of the relic with its tiny face, in his discussion of the furore over Garnet’s posthumous agency. But the title-page of this particular copy (now in the British Library) also testified to a reader’s agency: it had, boldly inscribed beneath the title, the flourished signature of ‘Wm Neile’; further down the page on the right-hand side, the name ‘Jo Neile’.

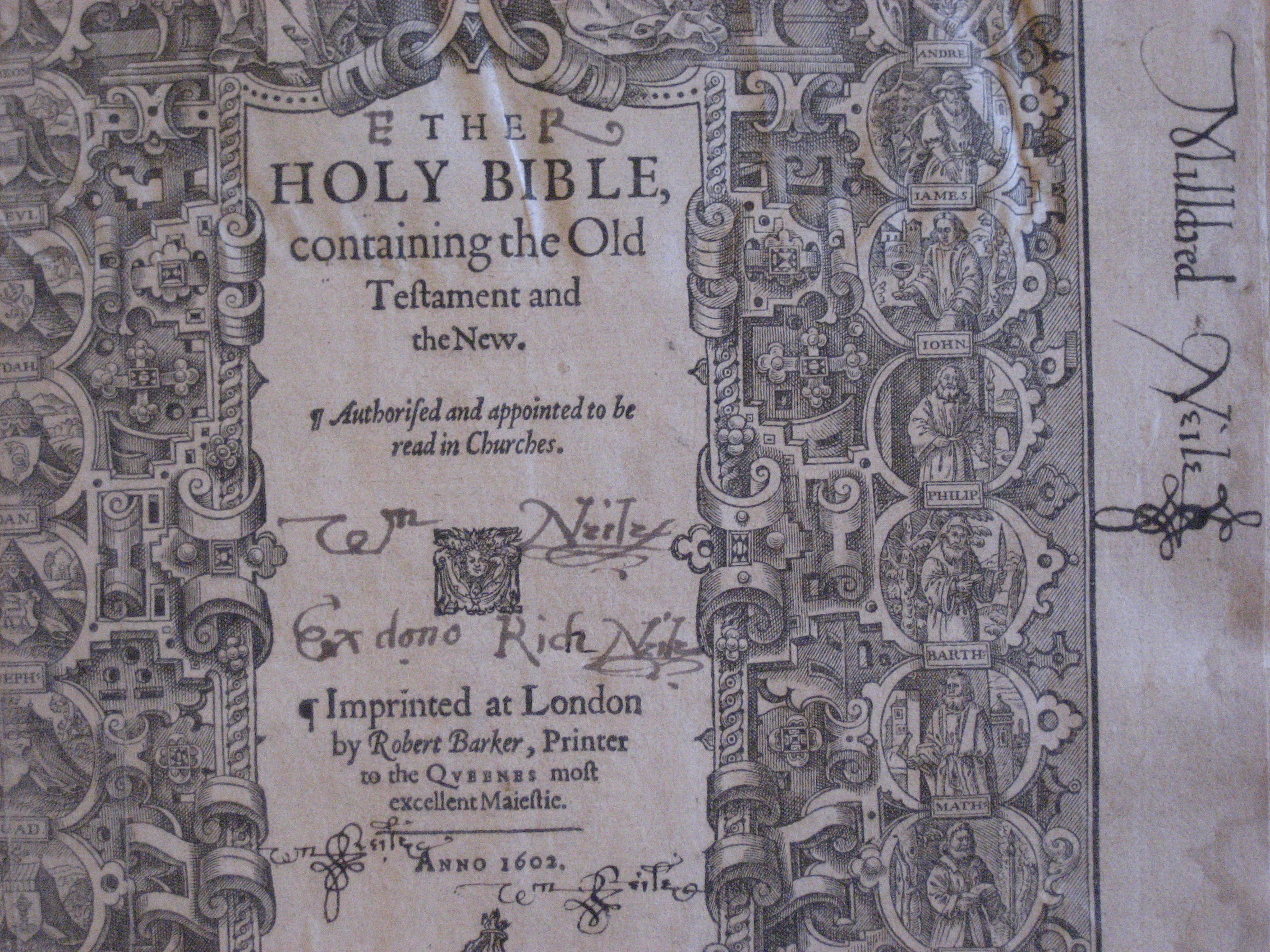

I’d seen that name before, and I would see it again, most prominently in a lavishly-bound 1602 Bible (possibly the former property of the dying Queen Elizabeth I) in the library of my own Cambridge college, Gonville and Caius. Here it was, again, involved in quite a showy performance–Neile signs his name three times, adds a note to the effect that the book was a gift from his brother Richard, and parades the name ‘Milldred Neile’ down the right-hand margin. I began to look out for Neile books, and to type the occasional idle provenance search into library catalogues that allow for such things.

I’d seen that name before, and I would see it again, most prominently in a lavishly-bound 1602 Bible (possibly the former property of the dying Queen Elizabeth I) in the library of my own Cambridge college, Gonville and Caius. Here it was, again, involved in quite a showy performance–Neile signs his name three times, adds a note to the effect that the book was a gift from his brother Richard, and parades the name ‘Milldred Neile’ down the right-hand margin. I began to look out for Neile books, and to type the occasional idle provenance search into library catalogues that allow for such things.

In the end I came up with a list of about 25 books, and it seemed to me to be an interesting list. There were plays–including John Day’s controversial The Ile of Guls, which ran into serious trouble for its attacks on the Scottish in the first years of the Stuart monarchy; a Jacobean masque, Middleton and Rowley’s The World Tost at Tennis, attacking extravagant clothing; and an old interlude called New Custom. There was page-turning romance (Barnabe Rich’s Don Simonides) and urban reportage (Thomas Dekker’s The Dead Terme). There was a helpful book to teach you how to boast like a Spaniard (Jacques Gaultier’s Rodomontados. Or, Bravadoes and bragardismes). There was religious literature–Latimer’s sermons, a life of Archbishop of Canterbury John Whitgift, more anti-Catholic polemic in various shapes and sizes. Above all, though, there was news, news about embassies to Spain, victories over the Turk, the villainies of the Catholic League, the coronation and later the burial of Henri IV. All of these titles showed signs of attentive reading, in the form of rapid pencil marks in the margins. The collection offered a scratch-portrait of a man-about-town, reading all kinds of things to keep himself informed, entertained and properly prejudiced. Here was a clear-cut case of what I call a ‘polyreader’, a reader on the lines of the poligrafi or ‘polywriters’ who wrote in many different modes to feed the hungry presses of Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Little more than a century after the arrival of print in England, here was the man that books built.

So who was this unknown reader? He was born in 1560, in the parish of St Margaret’s, Westminster, with which he would retain a lifelong association. In his early years, he appears to be have been a servant of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, the most powerful man in the land. He worked closely with his younger brother Richard, who was a household chaplain of Cecil’s at the start of a stellar career that took him from Dean of Westminster, via the  bishoprics of Rochester, Lichfield and Coventry, Lincoln, Durham, Winchester, to the Archbishopric of York. William seems to have spent the rest of his life clinging to Richard’s coat-tails, getting various posts in Westminster during his brother’s time there, and becoming his brother’s steward from 1612. He was himself ordained in 1616, and got a living at Sutton-in-the-Marsh, Lincolnshire; he died in 1624. After his death Richard went through William’s almanacs, stretching back to 1593, extracting notes on births, marriages, deaths, debts and freak weather, such as ‘A fearfull thunder one Crack lastinge neere halfe an hower’. (My thanks to Andrew Foster, who wrote the entry on Richard in the new DNB, for some of these biographical details).

bishoprics of Rochester, Lichfield and Coventry, Lincoln, Durham, Winchester, to the Archbishopric of York. William seems to have spent the rest of his life clinging to Richard’s coat-tails, getting various posts in Westminster during his brother’s time there, and becoming his brother’s steward from 1612. He was himself ordained in 1616, and got a living at Sutton-in-the-Marsh, Lincolnshire; he died in 1624. After his death Richard went through William’s almanacs, stretching back to 1593, extracting notes on births, marriages, deaths, debts and freak weather, such as ‘A fearfull thunder one Crack lastinge neere halfe an hower’. (My thanks to Andrew Foster, who wrote the entry on Richard in the new DNB, for some of these biographical details).

Last week I finally got my hands on Will’s will, which turns out to be quite a document. The principal bequests are to his children, who are given various bizarre/delightful combinations of weapons and armour, musical instruments, chests and boxes, and money. (In a later codicil William laments the fact that he seems to have spent all the money, so the gifts have to be scaled down somewhat). But above all, he gives books, and in the process he puts my modest reconstruction of his reading in perspective. To Mildred, his eldest daughter, he gives 100 books. To Richard, his eldest son, he gives 200. Then William and John also get 200 each, while Dorothy and Frances have to make do with just 40 apiece; but newborn Robert, since he’s male, gets 100. Each of the books has, the will informs us, been individually assigned with the name of the recipient written on the title-page–as we saw with the 1602 Bible (for Mildred) and Garnet’s straw (for John), above.

So there is some work to be done here. I have about 25 books, but it would be nice to locate the remaining 855. If you find one, let me know (jes1003@cam.ac.uk)!