At a meeting of the Cambridge Digital Humanities Network yesterday I was belatedly introduced to dh23things–a site that has been put together to introduce early careers humanities researchers to digital tools that might be useful for their research. It’s full of useful links & enlightening commentary–useful for mid- and late- and falling-off-the-end-of-their-career people too.

At a meeting of the Cambridge Digital Humanities Network yesterday I was belatedly introduced to dh23things–a site that has been put together to introduce early careers humanities researchers to digital tools that might be useful for their research. It’s full of useful links & enlightening commentary–useful for mid- and late- and falling-off-the-end-of-their-career people too.

Tuesday morning, 8.10 am, Ben’s cello lesson. He’s only eight so he has to have something to get his knees up to the right height. At home, it’s the poor neglected Latin and Italian dictionaries. At the teacher’s house, it’s a copy of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations and England’s Thousand Best Houses.

Tuesday morning, 8.10 am, Ben’s cello lesson. He’s only eight so he has to have something to get his knees up to the right height. At home, it’s the poor neglected Latin and Italian dictionaries. At the teacher’s house, it’s a copy of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations and England’s Thousand Best Houses.

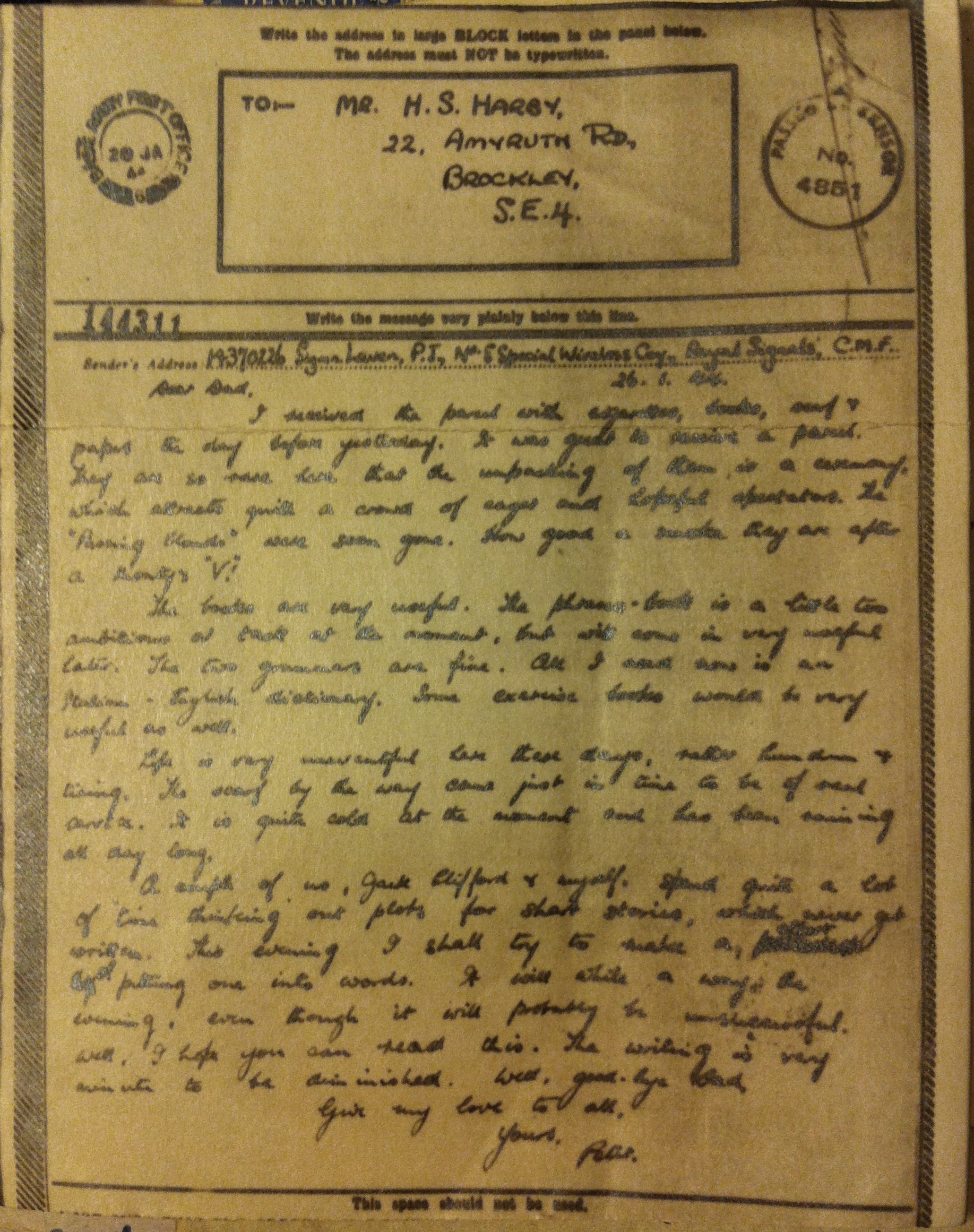

In odd moments over the last few days I’ve been absorbed in reading a pile of letters that my father-in-law sent home during World War II. He was stationed in North Africa, Italy and Austria, and the letters mostly confirm the received story: that dear old Peter never saw any of the fighting and spent most of the war sitting in an olive grove reading a book.  Well, perhaps that’s not quite fair. There are plenty of letters that dwell on the discomforts–mud, snow, leaking tents, rabid dogs, bugs, scorpions, and above all the sheer tedium of life in khaki, the sense of your youth being sucked away by events that are beyond your control or comprehension. But there are also lyrical descriptions of the landscape, reports back on the latest concerts and operas, endless requests for more cigarettes, and numerous references to books, which were evidently one of the best antidotes to the boredom and to the impersonality of army life.

Well, perhaps that’s not quite fair. There are plenty of letters that dwell on the discomforts–mud, snow, leaking tents, rabid dogs, bugs, scorpions, and above all the sheer tedium of life in khaki, the sense of your youth being sucked away by events that are beyond your control or comprehension. But there are also lyrical descriptions of the landscape, reports back on the latest concerts and operas, endless requests for more cigarettes, and numerous references to books, which were evidently one of the best antidotes to the boredom and to the impersonality of army life.

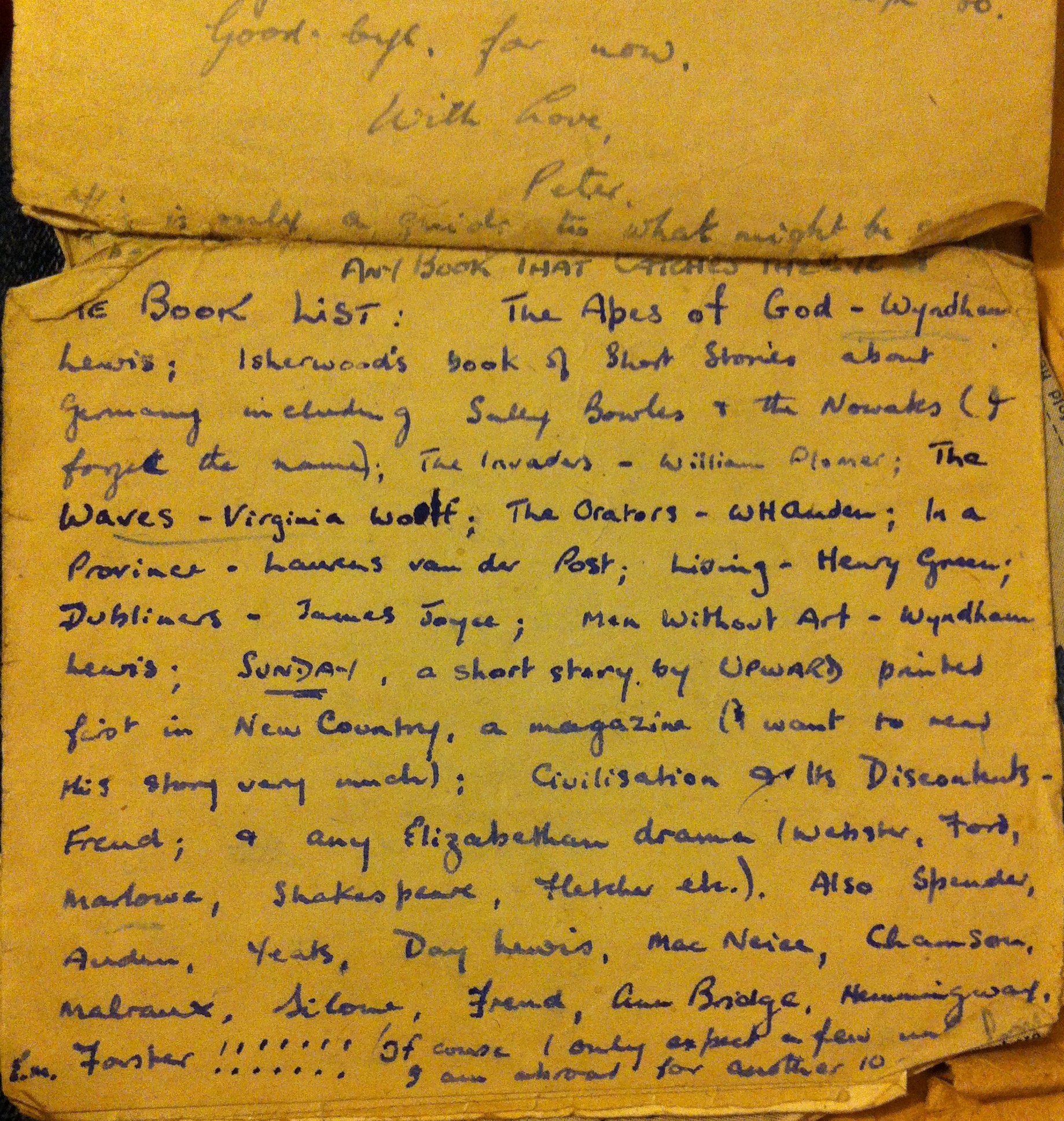

And what a lot of books were travelling out to that olive grove. Vera Brittain, Rosamond Lehmann, Henry James, Virginia Woolf, Shakespeare, Christopher Isherwood, W. H. Auden… he reads them all and sends back detailed comments to his (possibly perplexed) dear mother and father. The wish-list you see here gives some idea of the canon as it appeared in June 1944: from Wyndham Lewis to E. M. Forster via Plomer, Green, Joyce, Upward, Freud, any Elizabethan dramatist and a host of poets. The letters bring home the cultural significance of Penguin, as Peter asks for a subscription to Penguin New Writing, delights in the world opened up by Penguin Modern Painters, and asks for any Penguin guides to European countries. You also feel the strength of his desire to pick up the local languages, as he begs for grammars and dictionaries to reinforce the effects of halting conversations with the locals and (in Italy) with Giacomino, the boy who became for a time his main language tutor. He was a producer as well as a consumer, co-editing a magazine called ‘Swill’ that ran for at least two issues, and putting on a one-act miracle play by Alex Comfort (a writer whose extensive oeuvre would later be eclipsed by just one of his works, The Joy of Sex).

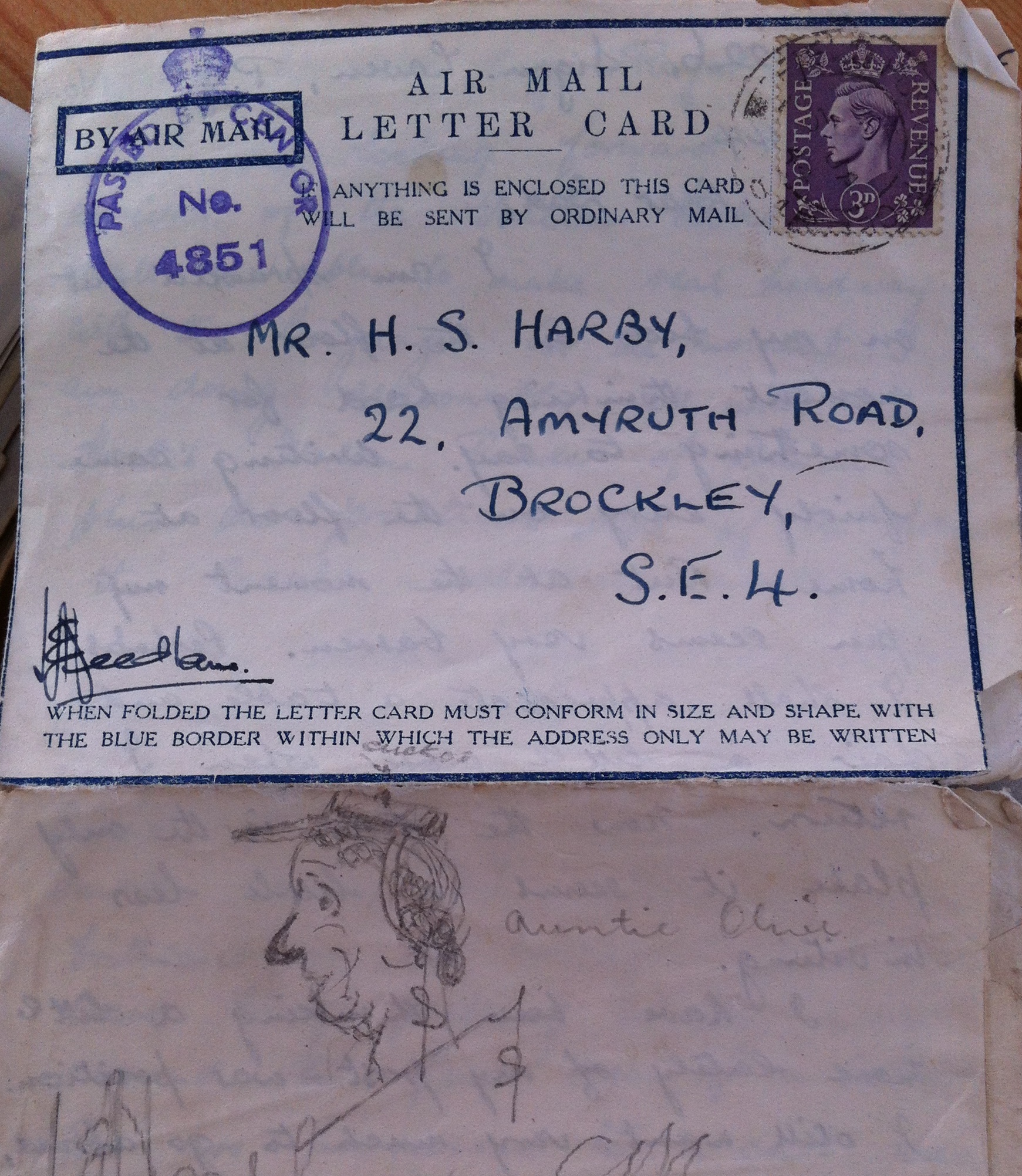

The material stuff of the letters has its own fascination. Most of them are written on single sheets of air-mail paper, with signed declarations on the outside to the effect that the contents don’t stray beyond personal or family matters.

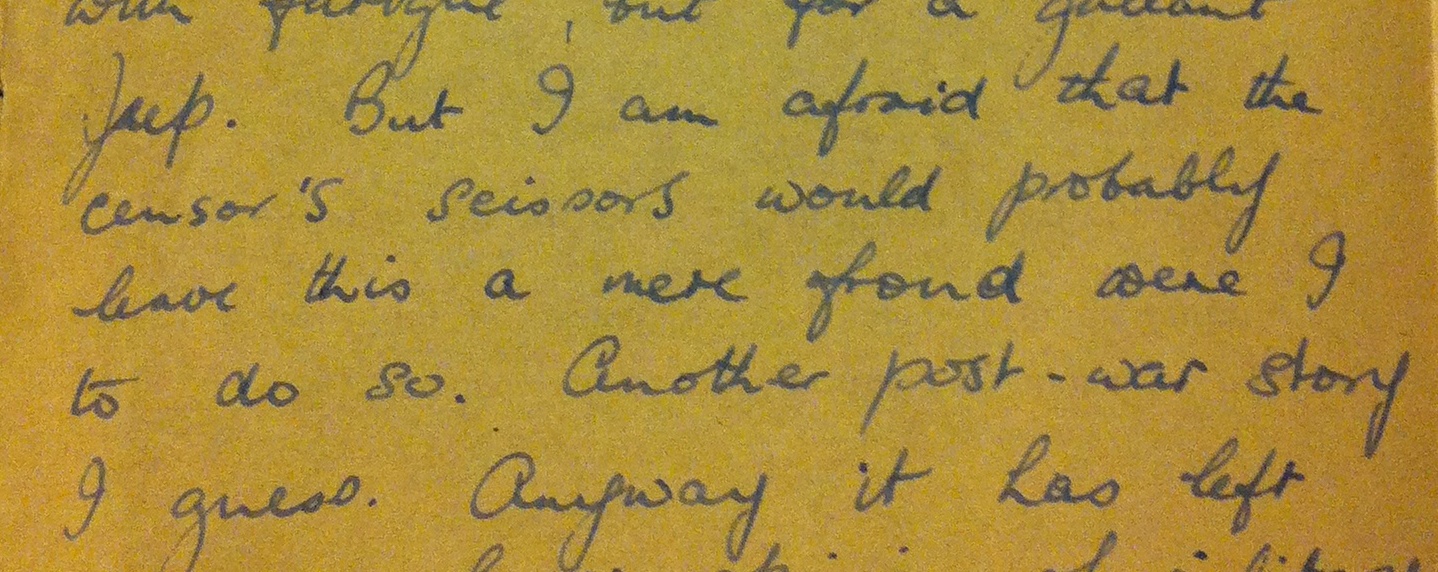

The material stuff of the letters has its own fascination. Most of them are written on single sheets of air-mail paper, with signed declarations on the outside to the effect that the contents don’t stray beyond personal or family matters.  One refers explicitly to the ‘censor’s scissors’ which would make ‘a mere frond’ of a letter if it continued on a particular topic. The letters are covered, as you might expect, with multiple stamps and declarations marking the activities of the censor; one of them also has a doodle of ‘Auntie Olive’, presumably executed at a later stage. And then there’s a particularly strange kind of letter which appears to have undergone a shrinking process, such that poor old mum and dad would need to find a magnifying glass to be able to read it. Can anyone explain what’s going on here?

One refers explicitly to the ‘censor’s scissors’ which would make ‘a mere frond’ of a letter if it continued on a particular topic. The letters are covered, as you might expect, with multiple stamps and declarations marking the activities of the censor; one of them also has a doodle of ‘Auntie Olive’, presumably executed at a later stage. And then there’s a particularly strange kind of letter which appears to have undergone a shrinking process, such that poor old mum and dad would need to find a magnifying glass to be able to read it. Can anyone explain what’s going on here?

Reading the correspondence is something of a guilty pleasure. Peter was acutely embarrassed by his memory of what his 21-year-old self had written home, and wanted it all destroyed; so the letters were hidden from him during his lifetime, only to be dug out after his death in 2004. You can’t help but sense his mortification as you read. But after the war, he became a historian, and perhaps (just perhaps) the historian in him would have forgiven me for my interest in this cache of ancient manuscripts.

Reading the correspondence is something of a guilty pleasure. Peter was acutely embarrassed by his memory of what his 21-year-old self had written home, and wanted it all destroyed; so the letters were hidden from him during his lifetime, only to be dug out after his death in 2004. You can’t help but sense his mortification as you read. But after the war, he became a historian, and perhaps (just perhaps) the historian in him would have forgiven me for my interest in this cache of ancient manuscripts.

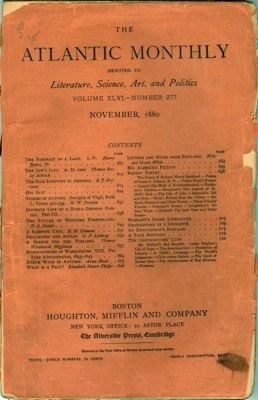

At last night’s American graduate seminar in the English Faculty, Tamara Follini and Adrian Poole discussed their work on the Cambridge Edition of the Complete Fiction of Henry James. This ‘historical’ edition, based on the first editions rather than the texts that James selected and revised for the New York Edition, is expected to run to 30 volumes, under 34 separate editors. After six years, none of the volumes has yet appeared, although it’s clearly not for lack of sweat.

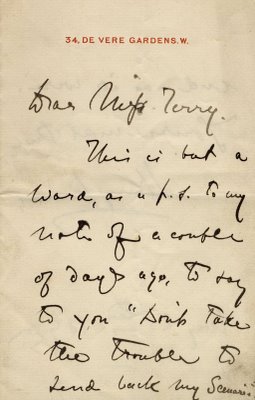

Adrian Poole took on The Princess Casamassima knowing that he would have to negotiate the relationship between the text as it appeared in instalments in the Atlantic Monthly and in subsequent volume publications, but only later learning (to his delight and horror) that there was also a surviving manuscript. This led him into the thorny thicket of James’s handwriting, and to a particular  letter in which James had apologized for the ‘…………. [word illegible] of my handwriting’. The what of my handwriting? After much staring and puzzling, Poole recovered the word: ‘anfractuosities’, meaning ‘winding or tortuous crevices, channels, passages’. (The OED helpfully points to Roderick Hudson, which refers to ‘chance anfractuosities of ruin in the upper portions

letter in which James had apologized for the ‘…………. [word illegible] of my handwriting’. The what of my handwriting? After much staring and puzzling, Poole recovered the word: ‘anfractuosities’, meaning ‘winding or tortuous crevices, channels, passages’. (The OED helpfully points to Roderick Hudson, which refers to ‘chance anfractuosities of ruin in the upper portions  of the Coliseum’). This was just one of the challenges presented by a text which was composed in England for serial publication in America, with proof sheets criss-crossing the Atlantic and the writer increasingly running late with his ‘too damnably voluminous’ submissions.

of the Coliseum’). This was just one of the challenges presented by a text which was composed in England for serial publication in America, with proof sheets criss-crossing the Atlantic and the writer increasingly running late with his ‘too damnably voluminous’ submissions.

The Wings of the Dove is Tamara Follini’s charge, and although the textual situation there is simpler, there is still an unresolved problem about whether to choose the English or the American first edition as copy-text. Cue hundreds of hours of variant-checking, sometimes over the kitchen table with other family members roped in to read aloud. Follini’s particular worry was annotation. The editors have vowed to refrain from offering purely interpretative notes, and to rein in any tendency to speculation, but this still leaves a question about how far one should go in glossing subtle literary allusions and intertextual references that might bear on a passage. Is there such a thing as a non-interpretative footnote? And how do you signal the presence of annotation without disrupting the reading experience and (at worst) upstaging the text?

For all their anxieties, these editors seemed to be enjoying their Herculean labours. Whatever else it may be, an edition is a declaration of love for a book or a writer; and Poole and Follini are still deeply in love with James.

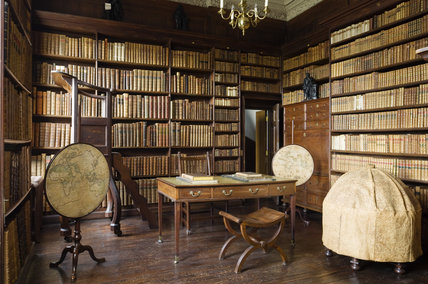

Last Friday the CMT hosted a one-day, AHRC-funded seminar on National Trust Libraries, organized by Dr Abigail Brundin of the Cambridge Italian Department. 45 librarians, curators, academics and postgraduate researchers from up and down the country came together to discuss ‘Mobility and Exchange in Great House Collections’, and to celebrate the unveiling of a new resource for cultural history.

Everyone who has been to a NT property will have had the experience of visiting the library and seeing rows and rows of books, intriguing but inaccessible, lining the shelves. Did they really matter? Or were they (as the cliché has it) bought by the yard by unthinking aristos who hoped they would help to keep out the cold? Only now, as the cataloguing of the Trust’s collections reaches its conclusion, can we begin to answer that question.

Everyone who has been to a NT property will have had the experience of visiting the library and seeing rows and rows of books, intriguing but inaccessible, lining the shelves. Did they really matter? Or were they (as the cliché has it) bought by the yard by unthinking aristos who hoped they would help to keep out the cold? Only now, as the cataloguing of the Trust’s collections reaches its conclusion, can we begin to answer that question.

The NT’s libraries are overwhelming in scale–over 140 collections, with 230,000 books in 400,000 volumes, much if not all of which is now catalogued in impressive copy-specific detail on COPAC. Both the cataloguing and the collections are overseen by the indefatigable Libraries Curator, Mark Purcell, who took us on a whistlestop powerpoint tour of his dominions. Like the houses, the libraries as he described them are complexly layered–brought together, broken up, moved around often over hundreds of years–so that understanding them requires a kind of archaeological reconstruction. Each library is a research project, or many research projects, waiting to happen. Purcell flashed up some of the highlights–masterpieces of printing or exceptionally rare titles–whetting the appetite for further exploration.

Elsewhere in the day, six papers illuminated different aspects of Great House library history. Guyda Armstrong (Manchester) kicked off with a discussion of the Chatsworth manuscript of Boccaccio’s De claris mulieribus, drawing out the pointed significance of presenting this discussion of good and bad women to Henry VIII, who had just executed his fifth wife, Catherine Howard, together with the daughter of the work’s translator, Lord Morley. Tracing the roundabout route by which the manuscript had made its way to the Chatsworth collection, Armstrong asked why the manuscript had always been so undervalued, and described some of the difficulties of gaining access to it today. John Gallagher (Cambridge) began his paper on ‘Reading and the Grand Tour’ by drawing a sharp contrast between the stasis of old books held in modern research libraries and the likely mobility of the same books in their early lives. His research shows how travellers bought, transported and discarded books according to the needs of the moment, often guided by their desire to pick up a fashionable smattering of a foreign tongue. Dunstan Roberts (Cambridge) followed this up with an account of the books that various generations of the Brownlow family of Belton House in Lincolnshire had bought on the Grand Tour. Putting the surviving books together with surviving lists of travel expenses provides a startlingly immediate sense of the priorities of eighteenth-century tourists, and of the cultural horizons that their journeys opened up. You can find sculptures by Canova in the Hermitage and Louvre, but there’s also one in the local church at Belton, thanks to the savvy of one heir to the family estates.

In the next session, Hannah Degroff (York) pointed to the difficulties of establishing exactly where books were kept in the historic house, in her case Castle Howard. The evidence is tantalizingly vague, but suggests that there may have been several separate collections within the house, and that these moved around in response to the changing circumstances of their ageing owner, the 3rd Earl of Carlisle. Susie West (Open University) extended that discussion by looking at the changing shape and location of aristocratic study libraries from the late seventeeth-century into the eighteenth century, during which time they moved from a position adjacent to the bedchamber to a more public situation where they worked as a variant of the parlour. Her study also challenged the tendency of literary historians to privilege the closet as a site of privacy and (especially female) agency; the fluidity of nomenclature in this period makes it hard to distinguish closets from studies, and the fluidity of room usage may muddy the waters still further. Finally Ed Potten (Cambridge University Library) asked why nineteenth-century libraries had received so little scrutiny. Focusing on the libraries at Nostell Priory and Tatton Park, he suggested that the idea of the ‘bibliophile’ or the ‘collector’ (or worse still, the ‘bibliomaniac’) obscured the intellectual vitality of bookbuying and reading in the period.

The seminar concluded with a round-table discussion chaired by David Pearson (London), along with Warren Boutcher (Queen Mary), Stephen Parkin (British Library), Nicholas Pickwoad (NT) and Jason Scott-Warren (Cambridge), which considered some of the key issues facing the NT libraries as their cataloguing programme draws to a conclusion. How will the Trust cope with the expanding pressure for access? How can we  balance increased access with the need to conserve the collections? How do we raise public awareness of the significance of these libraries? The last question generated the liveliest discussion: put simply, it will take money and labour to bring these libraries back to life, and nobody knows (yet) where that money and labour will come from.

balance increased access with the need to conserve the collections? How do we raise public awareness of the significance of these libraries? The last question generated the liveliest discussion: put simply, it will take money and labour to bring these libraries back to life, and nobody knows (yet) where that money and labour will come from.

You can keep up to date with the NT libraries by signing up to their Facebook page here. And the CMT is helping to organize an exhibition at Belton House between 2 March and 3 November 2013 which will showcase some of the fruits of its pilot project on Italian books in the library there–please come and see it!

There’s conflicting news about those ancient Malian manuscripts that were said to have been destroyed by Islamic militants fleeing Timbuktu. Reports coming out of the city suggest that many of these volumes were hidden away for safe keeping, so that the damage to the historic collections may be minimal.

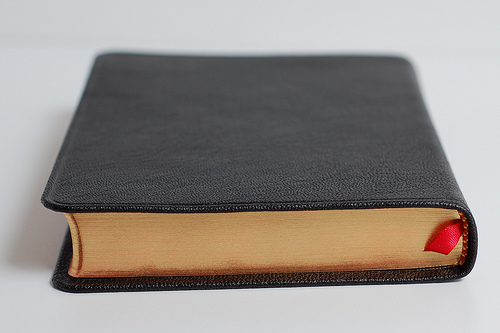

The History of Material Texts seminar in Cambridge heard last week about another way in which fighting in Mali might have an impact on the transmission of texts. Bob Groser, the Bibles Production Manager at Cambridge University Press, revealed that the Press binds some of its most up-market Bibles in Nigerian goatskin–the classic ‘Morocco’ leather. He was watching the unfolding events and worrying about a possible disruption of trade-routes that might seriously affect the price and availability of the skins.

The History of Material Texts seminar in Cambridge heard last week about another way in which fighting in Mali might have an impact on the transmission of texts. Bob Groser, the Bibles Production Manager at Cambridge University Press, revealed that the Press binds some of its most up-market Bibles in Nigerian goatskin–the classic ‘Morocco’ leather. He was watching the unfolding events and worrying about a possible disruption of trade-routes that might seriously affect the price and availability of the skins.

Something like this had, Groser explained, happened after the Japanese tsunami of 2011, which knocked out the paper mills that had been supplying the Chinese cigarette industry. All of a sudden the French mills which produce the kind of fine, opaque ‘Bible paper’ that you need to cram the text of Scripture into a small space redirected their energies to the Far Eastern fag trade–causing more headaches for CUP. (Apparently you can roll excellent cigarettes from a Bible–although Rizlas probably work out cheaper).

By the end of Groser’s talk, a CUP Bible had become a rather awe-inspiring transnational commodity, like your tablet or smartphone the product of an invisible network that spreads out across the globe. And there were many more juicy details along the way. Quite a lot of modern book leathers come from pigs, but CUP avoid pigskin, mainly because it’s infra dig–too lowly for the purpose (though why a goat or a cow should be more acceptable is not quite clear to me). And it turns out that you get just two bindings out of the average goatskin; the plentiful off-cuts go for reconstitution as bonded leather. And the binding is strongest if the spine of the book and the spine of the animal are aligned… the thought of which sends a faint shiver down my spine.

How do we rate the chances of Rob Stutzman and Jonathan Wheeler, the two Californians who are suing Penguin and Random House for fraud and false advertising in relation to Lance Armstrong’s memoirs? Newspaper reports state that they feel ‘cheated and betrayed’ after books that they bought as ‘non-fiction’ were revealed by the author to be a pack of lies.

How do we rate the chances of Rob Stutzman and Jonathan Wheeler, the two Californians who are suing Penguin and Random House for fraud and false advertising in relation to Lance Armstrong’s memoirs? Newspaper reports state that they feel ‘cheated and betrayed’ after books that they bought as ‘non-fiction’ were revealed by the author to be a pack of lies.

I imagine that the court case will result in some lucrative work for literary theorists, who could be called in to debate whether writing your own life isn’t always a fictional enterprise. Most celebrity memoirs aren’t even written by the person who claims to be the author, so the lies begin on the dust jacket. And even when the celebrity is actually holding the pen, you can scarcely expect an unadorned narrative to come from the horse’s mouth.

On the other hand, there must be a difference between airbrushing the story of your life and fabricating it outright. The genre of autobiography frequently relies on a high ideal of authenticity. If a holocaust memoir turns out to be fictional, there’s a storm of protest. Don’t we need to police the distinction between fiction and non-fiction in this sphere?

On second thoughts, let’s hope they settle out of court…

Appalling news today that the fighting in Mali has led to the destruction of the new Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu, with its extraordinary manuscript collections. The website of Tombouctou Manuscripts Online gives some idea of the riches of the Institute’s library, which testified to the vibrant literary culture of this commercial crossroads during its sixteenth-century heyday, when a library of 1600 books made you one of the less distinguished local scholars. Leo Africanus (al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan al-Fasi), in his 1526 treatise on Africa, described Timbuktu as a city where the King honoured learning, and where the trade in manuscripts generated more money than any other form of commerce.

Appalling news today that the fighting in Mali has led to the destruction of the new Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu, with its extraordinary manuscript collections. The website of Tombouctou Manuscripts Online gives some idea of the riches of the Institute’s library, which testified to the vibrant literary culture of this commercial crossroads during its sixteenth-century heyday, when a library of 1600 books made you one of the less distinguished local scholars. Leo Africanus (al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan al-Fasi), in his 1526 treatise on Africa, described Timbuktu as a city where the King honoured learning, and where the trade in manuscripts generated more money than any other form of commerce.

The city’s mayor puts it very succinctly when he says: ‘This is terrible news. The manuscripts were a part not only of Mali’s heritage but the world’s heritage’. Let’s hope that something can be salvaged from the rubble.

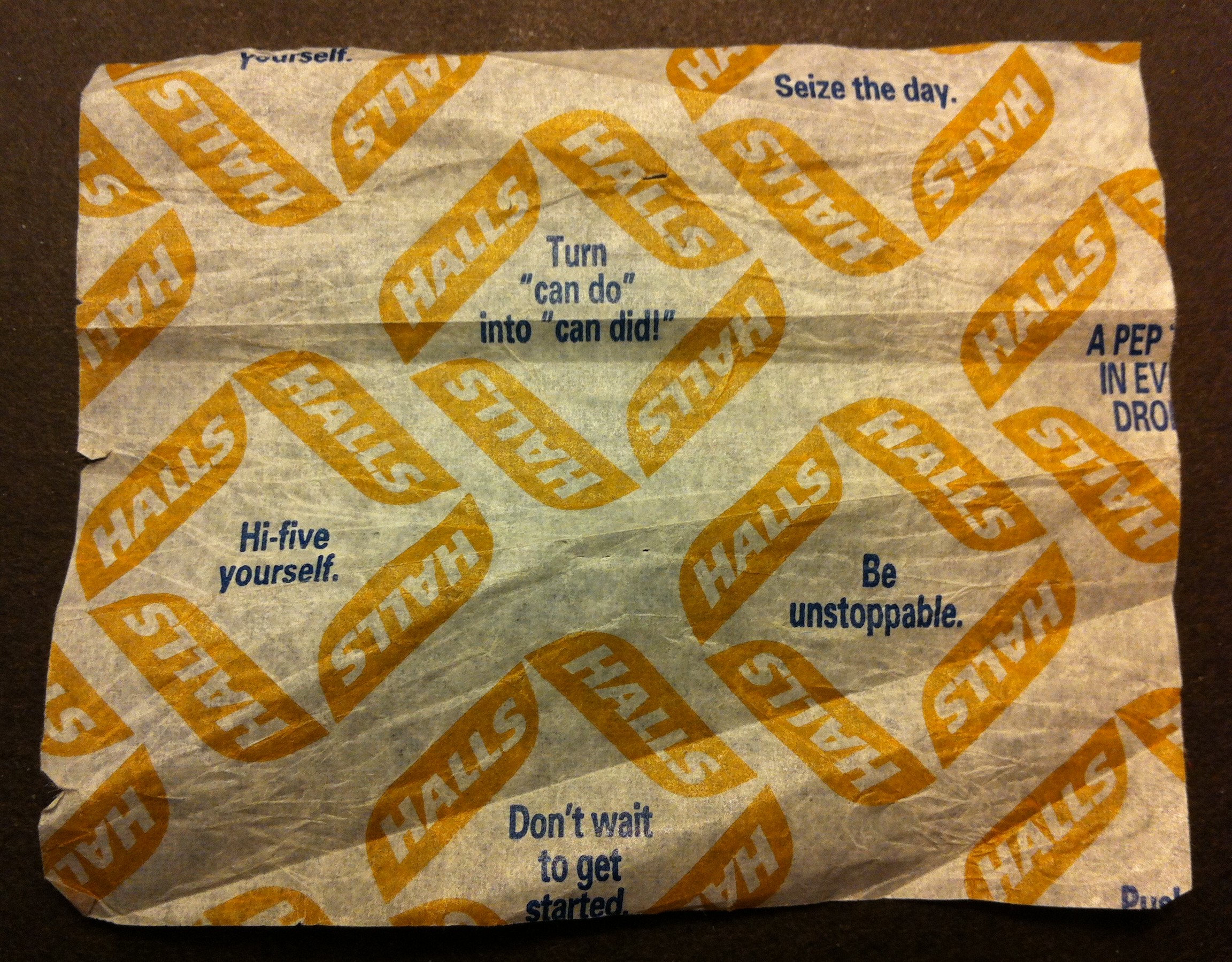

Anyone suffering from snuffles and sneezes at this time of year can take comfort from a cough-sweet that not only relieves your symptoms but also clobbers you with inspirational slogans. Some of them are a bit dubious: is it possible, or particularly cheering, to ‘hi-five yourself’? But the instruction to ‘Be unstoppable’ is undeniably helpful. There’s an impressive balance of old and new–the wacky ‘Turn “can do” into “can did!”‘ rubbing shoulders with the classical injunction to ‘Seize the day’.

Anyone suffering from snuffles and sneezes at this time of year can take comfort from a cough-sweet that not only relieves your symptoms but also clobbers you with inspirational slogans. Some of them are a bit dubious: is it possible, or particularly cheering, to ‘hi-five yourself’? But the instruction to ‘Be unstoppable’ is undeniably helpful. There’s an impressive balance of old and new–the wacky ‘Turn “can do” into “can did!”‘ rubbing shoulders with the classical injunction to ‘Seize the day’.

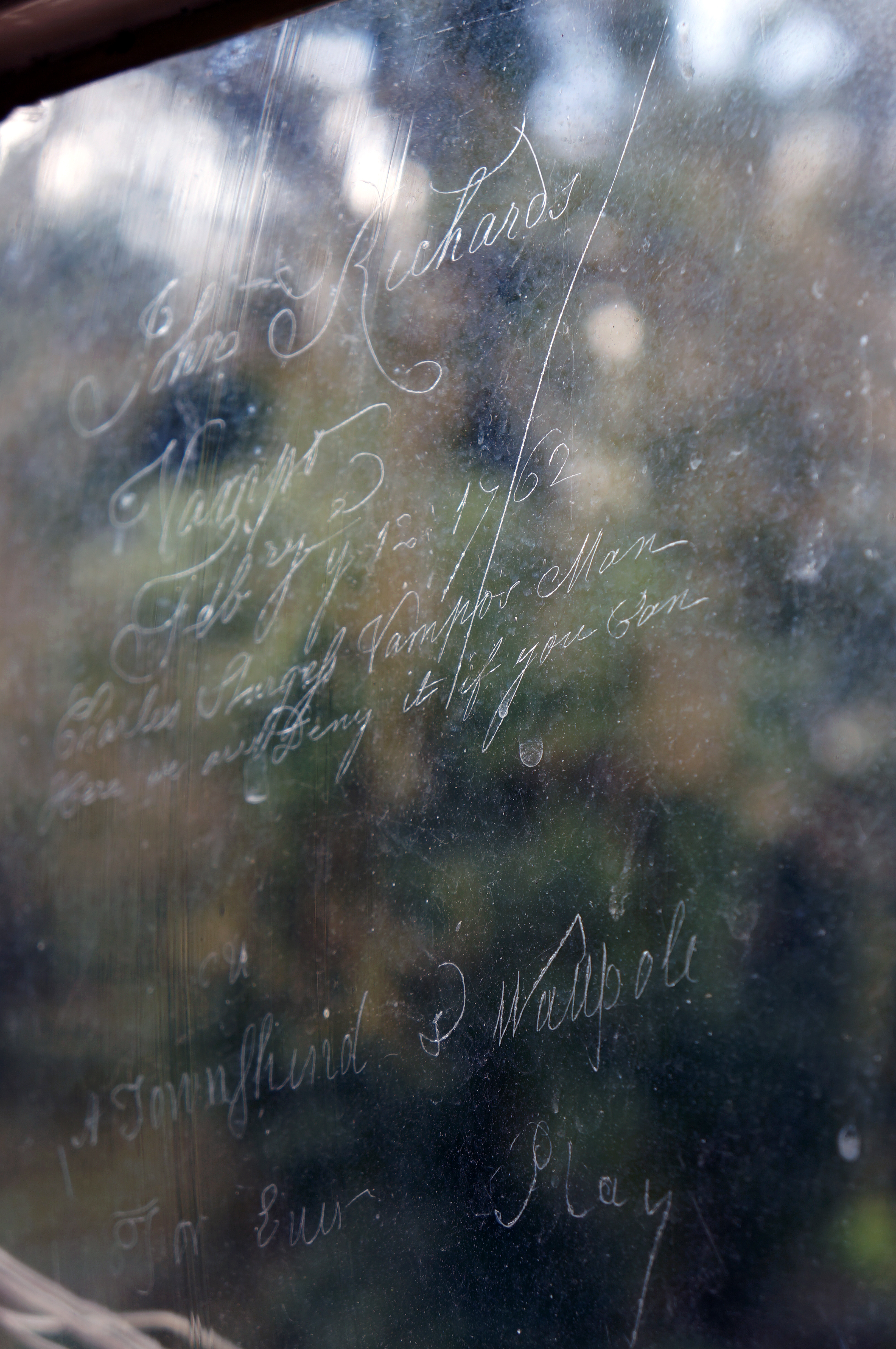

And of course this kind of thing goes back a long way. The sixteenth-century humanist, Desiderius Erasmus, urged students to keep the fruits of their reading ever before their eyes: ‘In the same way you will write some brief but pithy sayings such as aphorisms, proverbs, and maxims at the beginning and at the end of your books; others you will inscribe on rings or drinking cups; others you will paint on doors and walls or even in the glass of a window so that what may aid learning is constantly before the eye. For, although these measures seem trivial in themselves when taken singly, yet taken together they make a profitable addition to the treasury of knowledge’. Were he alive today, I think I know which brand of cough-sweet he’d be buying…