In odd moments over the last few days I’ve been absorbed in reading a pile of letters that my father-in-law sent home during World War II. He was stationed in North Africa, Italy and Austria, and the letters mostly confirm the received story: that dear old Peter never saw any of the fighting and spent most of the war sitting in an olive grove reading a book.  Well, perhaps that’s not quite fair. There are plenty of letters that dwell on the discomforts–mud, snow, leaking tents, rabid dogs, bugs, scorpions, and above all the sheer tedium of life in khaki, the sense of your youth being sucked away by events that are beyond your control or comprehension. But there are also lyrical descriptions of the landscape, reports back on the latest concerts and operas, endless requests for more cigarettes, and numerous references to books, which were evidently one of the best antidotes to the boredom and to the impersonality of army life.

Well, perhaps that’s not quite fair. There are plenty of letters that dwell on the discomforts–mud, snow, leaking tents, rabid dogs, bugs, scorpions, and above all the sheer tedium of life in khaki, the sense of your youth being sucked away by events that are beyond your control or comprehension. But there are also lyrical descriptions of the landscape, reports back on the latest concerts and operas, endless requests for more cigarettes, and numerous references to books, which were evidently one of the best antidotes to the boredom and to the impersonality of army life.

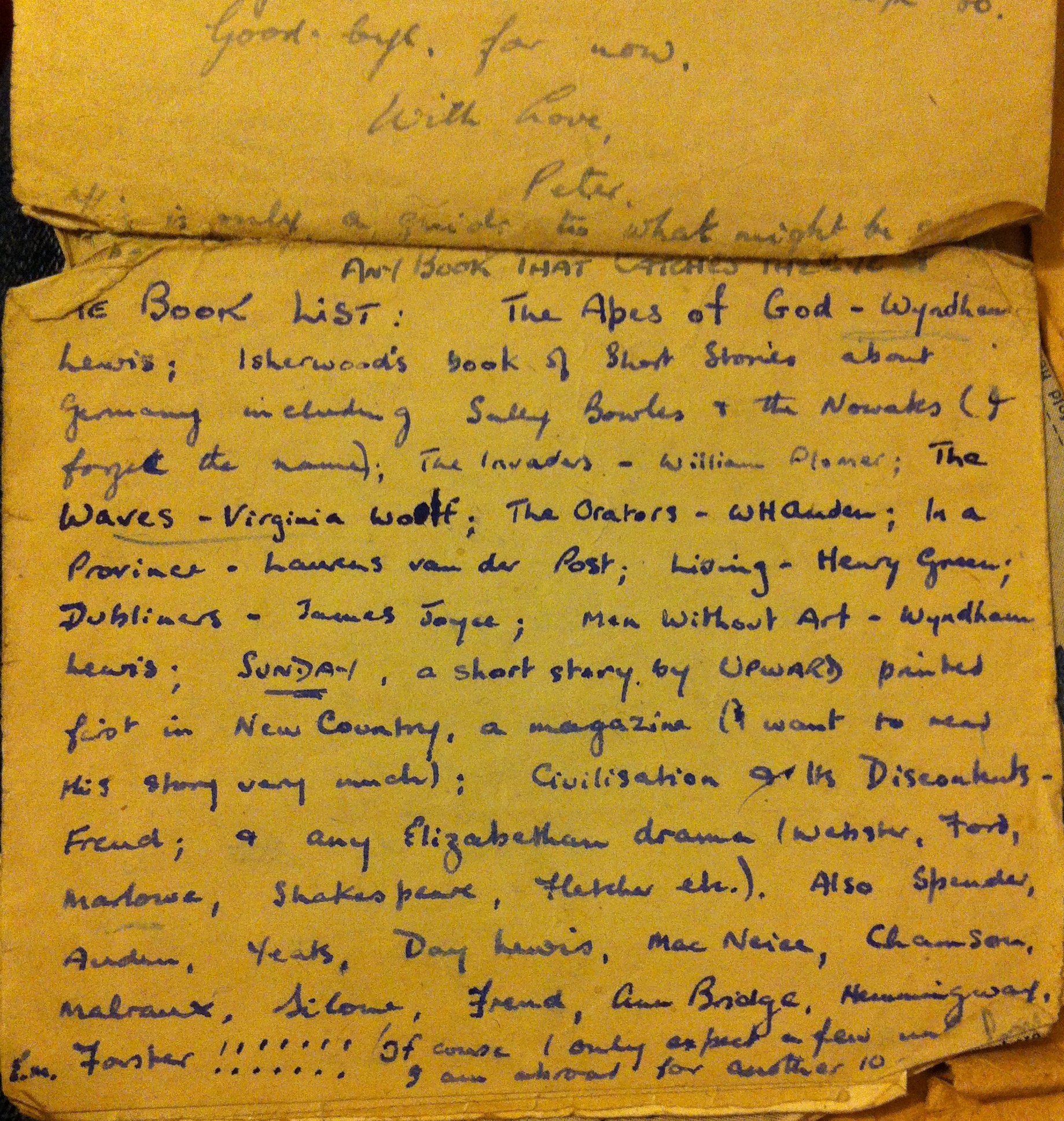

And what a lot of books were travelling out to that olive grove. Vera Brittain, Rosamond Lehmann, Henry James, Virginia Woolf, Shakespeare, Christopher Isherwood, W. H. Auden… he reads them all and sends back detailed comments to his (possibly perplexed) dear mother and father. The wish-list you see here gives some idea of the canon as it appeared in June 1944: from Wyndham Lewis to E. M. Forster via Plomer, Green, Joyce, Upward, Freud, any Elizabethan dramatist and a host of poets. The letters bring home the cultural significance of Penguin, as Peter asks for a subscription to Penguin New Writing, delights in the world opened up by Penguin Modern Painters, and asks for any Penguin guides to European countries. You also feel the strength of his desire to pick up the local languages, as he begs for grammars and dictionaries to reinforce the effects of halting conversations with the locals and (in Italy) with Giacomino, the boy who became for a time his main language tutor. He was a producer as well as a consumer, co-editing a magazine called ‘Swill’ that ran for at least two issues, and putting on a one-act miracle play by Alex Comfort (a writer whose extensive oeuvre would later be eclipsed by just one of his works, The Joy of Sex).

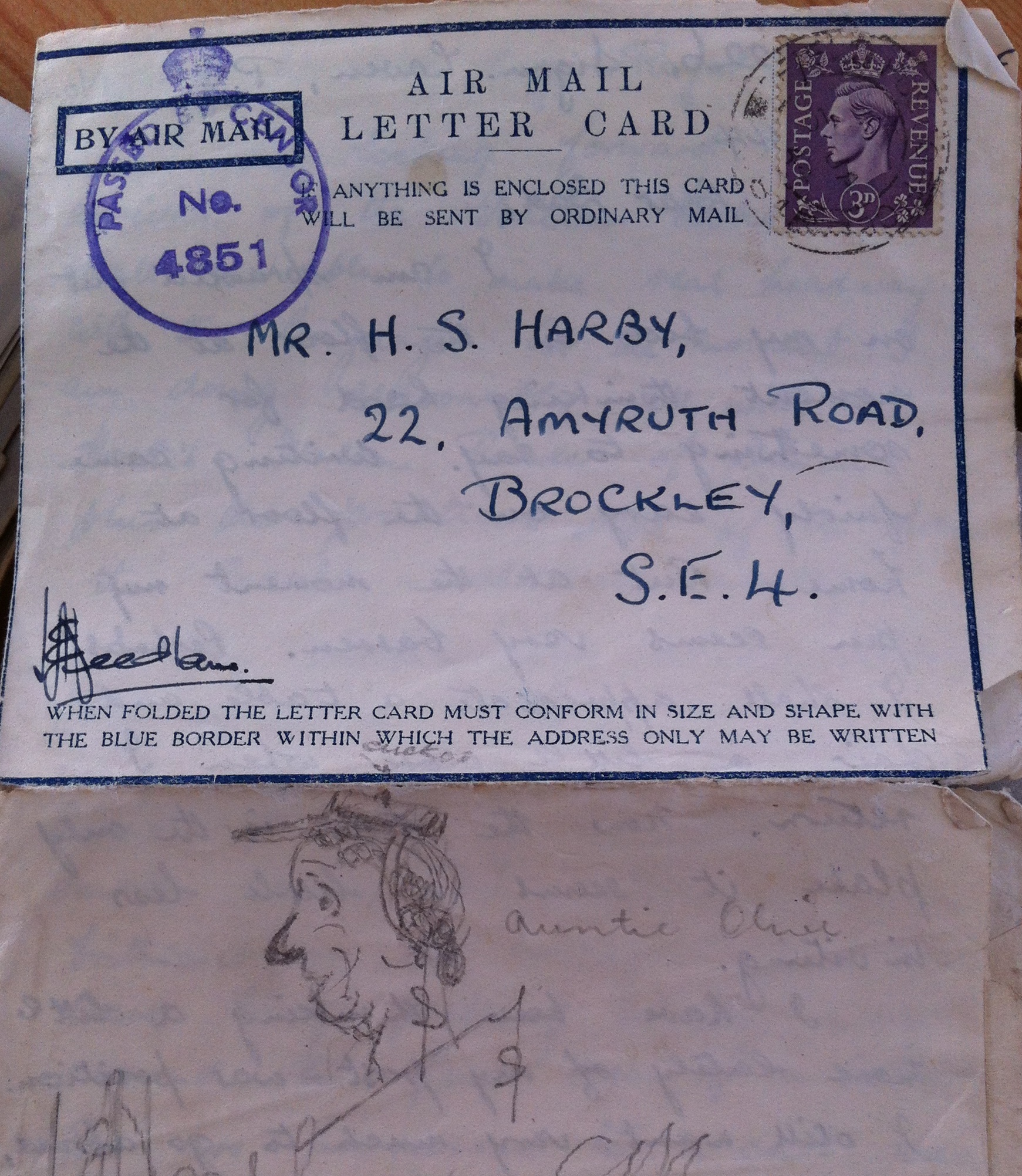

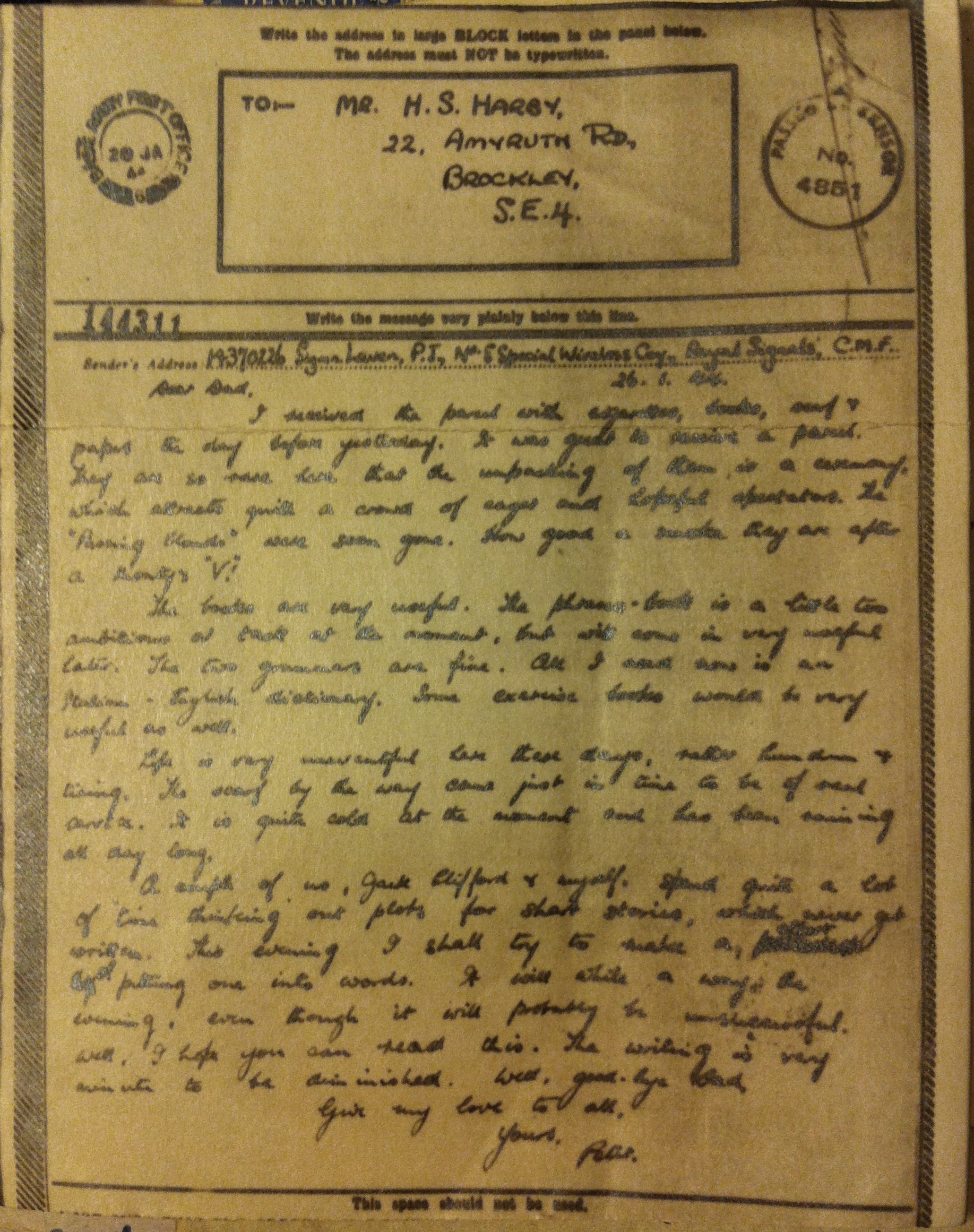

The material stuff of the letters has its own fascination. Most of them are written on single sheets of air-mail paper, with signed declarations on the outside to the effect that the contents don’t stray beyond personal or family matters.

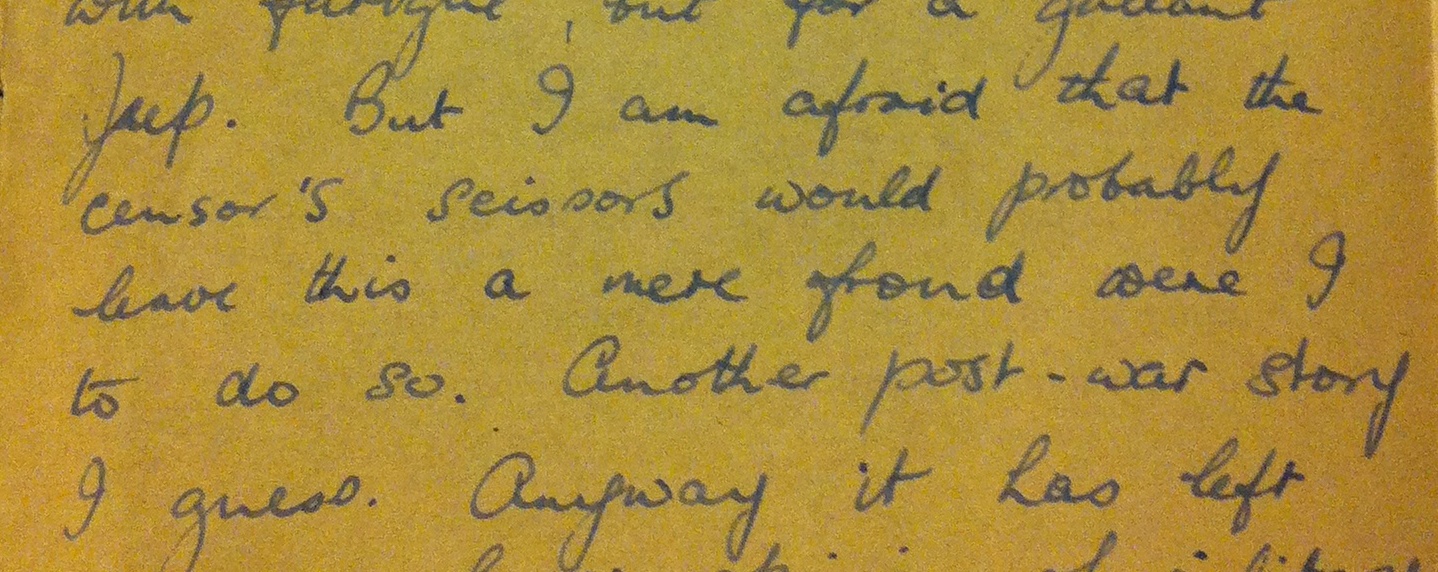

The material stuff of the letters has its own fascination. Most of them are written on single sheets of air-mail paper, with signed declarations on the outside to the effect that the contents don’t stray beyond personal or family matters.  One refers explicitly to the ‘censor’s scissors’ which would make ‘a mere frond’ of a letter if it continued on a particular topic. The letters are covered, as you might expect, with multiple stamps and declarations marking the activities of the censor; one of them also has a doodle of ‘Auntie Olive’, presumably executed at a later stage. And then there’s a particularly strange kind of letter which appears to have undergone a shrinking process, such that poor old mum and dad would need to find a magnifying glass to be able to read it. Can anyone explain what’s going on here?

One refers explicitly to the ‘censor’s scissors’ which would make ‘a mere frond’ of a letter if it continued on a particular topic. The letters are covered, as you might expect, with multiple stamps and declarations marking the activities of the censor; one of them also has a doodle of ‘Auntie Olive’, presumably executed at a later stage. And then there’s a particularly strange kind of letter which appears to have undergone a shrinking process, such that poor old mum and dad would need to find a magnifying glass to be able to read it. Can anyone explain what’s going on here?

Reading the correspondence is something of a guilty pleasure. Peter was acutely embarrassed by his memory of what his 21-year-old self had written home, and wanted it all destroyed; so the letters were hidden from him during his lifetime, only to be dug out after his death in 2004. You can’t help but sense his mortification as you read. But after the war, he became a historian, and perhaps (just perhaps) the historian in him would have forgiven me for my interest in this cache of ancient manuscripts.

Reading the correspondence is something of a guilty pleasure. Peter was acutely embarrassed by his memory of what his 21-year-old self had written home, and wanted it all destroyed; so the letters were hidden from him during his lifetime, only to be dug out after his death in 2004. You can’t help but sense his mortification as you read. But after the war, he became a historian, and perhaps (just perhaps) the historian in him would have forgiven me for my interest in this cache of ancient manuscripts.