Launched today, the British Newspaper Archive digitizes millions of newspapers published between (roughly) 1700 and 1950. Sadly, it’s a subscription service–but also a godsend to research in innumerable fields. Click here to have a look.

Linda Bree came to talk to the History of Material Texts seminar last week, on the subject of ‘Scholarly Publishing and Technological Change’. As someone who knows the world of academic publishing from every possible direction–Linda is Editorial Director for Arts and Literature at Cambridge University Press, and a scholar working on the ‘long eighteenth century’–she is uniquely placed to tell us what is going on out there, and her talk was indeed eye-opening.

As someone who subscribes to the scholarly orthodoxy that new technologies don’t replace old technologies, but force creative adaptation, I had completely missed what to her was the most important feature of the current landscape: digital printing, and Print-On-Demand technology. Although POD can be unreliable (do you really trust Amazon to deliver you a decent facsimile of that novel from 1833?), for scholarly publishers it is transformative. It gives old books a new lease of life (CUP calls its project to digitize its back-catalogue the ‘Lazarus programme’!) and allows supply to be more closely tailored to demand for new books. It also promises to make publishing leaner and greener, since digital files can be printed out in locations across the world, cutting transportation costs. And you may be able to have a book freshly printed by your local bookshop, if something like the Blackwell’s ‘Espresso Book Machine’ takes off more widely.

Other areas of the picture Bree painted were more murky. The question of how libraries will survive when they are spending their budgets not on buying books but on renting digital content; or of how publishers will survive as the web fosters the illusion (or the ideal) that content should come for free–these were left hanging. In the short term, though, it seems that the physical book will remain the medium of choice for academic monographs. If you’ve got to read a big chunky book full of footnotes, cross-references, and appendices, a book that you may want to scribble on and store away for future reference, ink on paper remains indispensable. For now.

The novelist Jeanette Winterson has just published her autobiography, entitled Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, and on Saturday the Guardian Review published an extract from it. The broad outlines of the story are familiar to anyone who has read her Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (or who has seen the TV adaptation). A magnificently mirthless Pentecostal Christian woman living in a two-up, two-down terraced house in Accrington adopts a daughter who becomes the principal victim of her oppressive domestic regime. Among the many bans to which the young Winterson is subject is a ban on literature–she’s not allowed to read books, because ‘the trouble with a book is that you never know what’s in it until it’s too late’. ‘Too late for what?’, the girl wonders, sensing a world of pleasures and dangers that lies just out of view.

The story from there unfolds rather like the inspiring autodidact narratives that Jonathan Rose collected in his study of The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes (2001). It’s the tale of an individual empowered by books, and above all by the books in the local library, which in Accrington was a stone building finished in 1908 with money from the Carnegie Foundation, with carved heads of Shakespeare, Milton, Chaucer and Dante outside and the words ‘KNOWLEDGE IS POWER’ on a giant stained-glass window within. There, Winterson remembers, she worked her way through the fiction section, starting with A for Austen. But she also bought herself books, which she hid under her mattress in layers composed of 72 paperbacks each. She was, she recalls, ‘going up in the world’ until her mother found the hidden treasures, threw them all out of the window into the backyard, and set light to them, leaving only charred fragments behind.

The event was, in Winterson’s retelling, foundational. Literature went inward: ‘The books had gone, but they were objects; what they held could not be so easily destroyed’. The bonfire of the vanities was the birth of the writer. But this writer is exceptionally alert to the inextricability of fact and fiction, and she must surely be aware of the resonance of her book-burning narrative. What went on in this terraced house in Lancashire is an uncanny recapitulation of the scene early in the first part of Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1605) in which the priest and the barber go through the mad knight’s library deciding which books to keep and which to massacre. The evil chivalric romances that have so beguiled Quixote are flung out of the window into the courtyard, where they are burnt to ashes by the housekeeper during the night. (Winterson’s burning is also a nocturnal event).

The main discrepancy between the two accounts is that Cervantes’ censors go through the books with some care, and find innumerable reasons to save their skins (ranging from sheer love, via the beauties of style, to personal associations: ‘Keep it back, because its author’s a friend of mine…’) They set the scene for a narrative that is enormously affectionate towards the absurd stories that it spoofs. No such luck for D. H. Lawrence and his companions in the twentieth century. They end up as ‘burnt jigsaws of books’, fragments which turn prose into broken poetry.

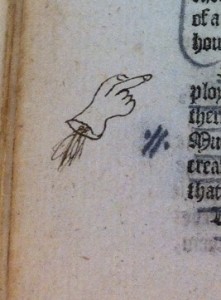

It’s over 20 years since Jonathan Goldberg published Writing Matter: From the Hands of the English Renaissance, a study of how early modern students were disciplined by their teachers to become at once fine penmen and docile subjects of the crown. I remember being sceptical, when I first read it, about Goldberg’s claim that the pen-holding hands depicted in writing manuals were actually being violently dismembered (‘the body and its natural life are menaced by writing’). But a couple of weeks ago I came across these pointing hands in the margins of a late sixteenth-century book.

It’s over 20 years since Jonathan Goldberg published Writing Matter: From the Hands of the English Renaissance, a study of how early modern students were disciplined by their teachers to become at once fine penmen and docile subjects of the crown. I remember being sceptical, when I first read it, about Goldberg’s claim that the pen-holding hands depicted in writing manuals were actually being violently dismembered (‘the body and its natural life are menaced by writing’). But a couple of weeks ago I came across these pointing hands in the margins of a late sixteenth-century book.

As Bill Sherman has taught us, in his more recent study Used Books, the manicule was one of the most important symbols that early modern readers used to process their reading. But although Sherman emphasizes the ‘excessive and quirky’ nature of many manicules, including those that emerge from elaborate ruffs, or sprout leaves and flowers, or turn phallic to mark discussions of male genitalia, I don’t think he has any that actually bleed. I’m just sorry that I’ve missed Hallowe’en for this post…

the manicule was one of the most important symbols that early modern readers used to process their reading. But although Sherman emphasizes the ‘excessive and quirky’ nature of many manicules, including those that emerge from elaborate ruffs, or sprout leaves and flowers, or turn phallic to mark discussions of male genitalia, I don’t think he has any that actually bleed. I’m just sorry that I’ve missed Hallowe’en for this post…

This week saw the premiere at the London Film Festival of ‘Anonymous‘, a film directed by Roland Emmerich which explores the theory that the works attributed to William Shakespeare were actually written by Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. The 17th Earl of Oxford was proposed as an alternative author in the early twentieth century by J. Thomas Looney, and although academic consensus rejects the idea, Looney continues to inspire some lively conspiracy theories today: see http://shakespeareidentified.com/ and http://www.shakespearefellowship.org/, for example…

Whereas conspiracy theory websites are by their nature niche, a film soon to be on general release has the potential to reach a great many people. Might cinema-goers up and down the country be so taken in by actor Rhys Ifans’s portrayal of the Earl of Oxford that the authorship rumours will become universally accepted, and Shakespeare pulled down from his pedestal? The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon is concerned and defensive, so much so that this week it launched an original publicity stunt to coincide with the London Film Festival screening of the offending film. On the road signs near his place of birth that proudly proclaim Warwickshire as ‘Shakespeare’s County’, Shakespeare’s name has been temporarily crossed out (see picture here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-coventry-warwickshire-15440882). With this very public protest the Trust draws attention to what it sees as an attempt to rewrite English culture and history, their censored road signs emblematising the idea that Shakespeare can’t simply be crossed out and replaced with another name.

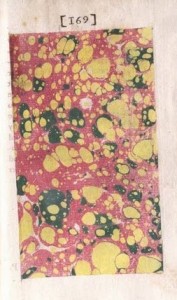

Bidding ends on 31 October for the 169 ’emblems’ created by a motley array of writers and artists to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Lawrence Sterne’s marbled page. Dropped into volume III of his enthralling, exasperating shaggy-mammoth story Tristram Shandy, the marbled page is proposed as a ‘motly emblem’ of the work as a whole, with its endless digressions, its unpredictable eddies and cross-currents, its colourful, chancy swirl of ideas. The Lawrence Sterne Trust are auctioning off 169 visual and verbal meditations on Sterne’s 169th page, and in true Sternean fashion are playing a game of anonymity–will you end up with a Quentin Blake, a Lavinia Greenlaw, a Ralph Steadman, an N. F. Simpson, an Iain Sinclair, a Lemony Snicket? The eye-watering exhibition can be viewed here.

Bidding ends on 31 October for the 169 ’emblems’ created by a motley array of writers and artists to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Lawrence Sterne’s marbled page. Dropped into volume III of his enthralling, exasperating shaggy-mammoth story Tristram Shandy, the marbled page is proposed as a ‘motly emblem’ of the work as a whole, with its endless digressions, its unpredictable eddies and cross-currents, its colourful, chancy swirl of ideas. The Lawrence Sterne Trust are auctioning off 169 visual and verbal meditations on Sterne’s 169th page, and in true Sternean fashion are playing a game of anonymity–will you end up with a Quentin Blake, a Lavinia Greenlaw, a Ralph Steadman, an N. F. Simpson, an Iain Sinclair, a Lemony Snicket? The eye-watering exhibition can be viewed here.

Reflecting on last Thursday’s History of Material Texts Seminar, given by John Rink from the Faculty of Music, brings me out in a fit of overblown adjectives. Rink has been at the helm of two extraordinary digitization projects, Chopin’s First Editions Online and The Online Chopin Variorum Edition. His talk took us through the bewildering profusion of different witnesses to Chopin’s scores–compositional drafts, presentation manuscripts, engravers’ manuscripts, proofs, multiple editions issued simultaneously in France, England and Germany–each of which might contain revisions–and printed copies marked up or elaborated by Chopin whilst he was teaching. That level of variability is an editor’s nightmare. (Even the celebrated ‘Funeral March’ from the Second Sonata was rethought and became a mere ‘March’ in some editions). But it’s meat and drink for a hypertext edition, which allows users to move between different versions, cross-compare, and put together their own text from the surviving evidence.

That said, the amount of work which goes into preparing such an edition–in terms not just of acquiring photographs of sufficient quality from archives across the world, but also of marking them up, bar-by-bar, so as to facilitate meaningful comparison between them–is prodigious. The results, though, are hugely worthwhile, since the application of new technologies raises fundamental questions about what a work of music actually is. Did this improvisational composer work towards a final, perfect goal, or did his pieces go on growing endlessly in different environments and different moments? How did publishers (including the women who actually engraved the music) go about regularizing and rationalizing Chopin’s sometimes idiosyncratic drafts? And how much license do performers today have in interpreting the textual evidence?

In questions, Rink suggested that it was fine for performers to pick and choose, in an informed way, from the different witnesses. He saw the quest for musical authenticity as often the enemy of important freedoms, imposing a rigid historicism on playing which in fact always takes place in the present. But he would presumably not condone re-opening Chopin to radical improvisation… How far should we go in our celebration of textual fluidity?

The New Yorker recently published an article about ‘the rise of bulletproof couture’, alerting us to the fact that every world leader worth his or her salt now has defensive panels sewn into a stylish coat or jacket. They’re mostly supplied by a company in Colombia and rely on a miracle formula that improves on Kevlar, the traditional petroleum-based monomer used in bulletproof jackets, which was invented by accident in a lab in the 1960s. The company ships its goods all over the world and is adept at adapting to local tastes–so it has safari vests for Nigeria, tunics for Dubai, and ecclesiastical vestments for Latin America. The churchmen have it easy–they can also buy ‘a bulletproof blanket, which can be thrown over a pulpit’ and ‘a large bulletproof Bible, which a priest can use, mid-sermon, as a protective shield’ (Sept 26, 2011, p. 71).

‘In an increasingly dangerous world threatened by terrorism and militant regimes, our soldiers, police, journalists, NGO workers and others from all walks of life are increasingly coming under fire, and what better a gift than the Bible which can withstand a bullet!’ So reads one website that offers to sell you a life-saving version of Holy Writ. Purists and completists beware: ‘to keep it light, and an easy fit in the backpack or breast pocket of those in the front line, we have just included the New Testament part of the American Standard Version (1901)’. Another such Bible looks like it doesn’t get much further than Genesis, but comes with a 20% discount for ‘active military with ID’. You can also buy versions with more impressive pedigrees–such as a World War II ‘soldier’s bible with a super hard steel metal cover. It was made to be carried in the left breast pocket to cover the heart. It is inscribed May The Lord Be With You.’ One careful owner…

All of this assumes that you need some special hard-binding to make a Bible bulletproof. But the ‘Iconic Books Blog‘ traces legends about soldiers whose lives were saved by the good book back into the nineteenth century, and finds that the latest examples come from the Iraq war. Meanwhile, don’t trust just any heavyweight book to save you. The latest crop of novels may take a while to read, but they can’t stop a bullet–as is proven here, by the doubtless horribly-biased people at Electric Literature.

Back in January, Amazon issued a fourth-quarter report that announced that sales of e-books for the Kindle outstripped sales of paperback books by 115:100, and sales of hardback books by 3:1. The inevitable newspaper reports followed, all pretty much drawing the same conclusions. It’s not a question of whether the patient will survive, they agreed; it’s how long he’s got left.

Well, another day, another death knell. Matthew Cain’s report on Channel 4 News last night revealed some troubling statistics. Overall sales of printed books are down 9.44%: paperbacks by 8.97%, hardbacks by 12.71%. As a consequence, publishers have begun to move away from the traditional model of issuing hardbacks a year in advance of paperbacks, with some titles going straight to the smaller and cheaper print format. ‘The most important catalyst for [this]’, Cain concluded, ‘has been the e-book’.

Remember the television advertisements for the Kindle and the iPad? Both Amazon and Apple sought to promote not only the whizzy gadgetry but also the physical sensation of using their products, and their durability (though I doubt any customers have held their new iPad in their hands while riding pillion on a moped, or let their dog lick their new Kindle). Using the Kindle or the iPad may provide a material experience, but does reading with them provide a material textual experience? Publishers, perhaps, have realised this, and are placing new emphasis on the aesthetic pleasure the hardback has to offer, and are promoting it as an object of physical beauty – in opposition, one assumes, to the rather dull featurelessness and intangibility of the e-book.

I don’t doubt, then, that e-readers and e-books have had an effect – a material effect, no less – upon the publishing industry. What I would dispute is the assumption – and assumption it is, for there is as yet no hard evidence of a causal relationship – that the rise in e-books has caused the fall in printed books. In media coverage, other factors are rarely discussed. Matthew Cain expressed concern that changes to the hardback could render it ‘a luxury gift item’, but at £15-25 a pop, is it not one already? What effect has the recession, falling real and disposable incomes and economic uncertainty about the future had upon people’s book-buying habits? Have rising commodity prices for wood pulp pushed up the price of books as they have the price of newspapers? What changes have there been to the second-hand book market? When was the last time you bought a brand-new hardback? (I can’t even remember).

So far, the news media have been content to stick to a ‘black-and-white’ style of reporting on e-books: e-media is up, print is down, therefore one caused the other, and the trend will continue. Much more research needs to be done into social and behavioural evidence, particularly on how e-books are being integrated into print culture, before any nuanced conclusions may be drawn about the future of the material text. Which socio-economic groups buy Kindles the most? How many printed books does the Kindle buyer already own? How often do new e-reader owners buy printed books, and how much do they spend? Do they use e-media and printed books in conjunction, and if so, how? What kinds of books are bought as e-books, what kind as printed? Crucially, for the e-reader is still in its infancy, for how long is a new Kindle used, and how does the frequency change over time? Are people buying the Kindle for the books, or for the novelty, or both?

In a short story in Granta 113 (‘Eva and Diego’, by Alberto Olmos), the female narrator explains the compulsion that drove her to buy a new iPod:

I had a salary that allowed me to buy approximately fifteen iPods a month…fifteen monthly temptations to buy an iPod. Consequently, I was one of those people who just had to buy an iPod. I simply have to buy whatever they’ve just invented to be bought…I bought the iPod out of boredom. But out of fear as well. Spending is about the fear of dying…Spending implies a future…

Spending on a gadget like a Kindle might imply a future, but books – physical books, material texts – declare both a past and a future, of the sophisticated but simple codex format, of communities of physical and intellectual experience, and of literary culture that e-readers cannot, in my opinion, hope to replicate.

A new book by the anthropologist Tim Ingold is always a reason for me to interrupt whatever I’m doing and to spend the next 24 hours reading, and his Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (Routledge, 2011), does not disappoint. Ingold’s mission is to show us how much our fashionable academic languages and intellectual schemas prevent us from understanding the way the world works. He ranges across the globe, drawing insights from numerous anthropological studies, but also from artists, writers, and musicians, and an eclectic array of thinkers past and present, in order to shake off our misperceptions of what life is. For Ingold, modern thought conspires against us, erecting a series of dyads–nature/culture, mind/body, subject/object–which are visible in (and reinforced by) the worlds we create around ourselves. Asphalt pavements, concrete roads, stiff leather shoes, chairs, prescribed gaits and upright postures all conspire to convince us that we stand over above the world rather than in it. The entrenched dichotomies of modern Western thought need not to be thought across or ‘deconstructed’ but thought around, strenuously, with a lot of help from those who would never have dreamed of making such distinctions, and much detailed reflection on the nature of our own experience.

Ingold would perhaps disapprove of the existence of a ‘Centre for Material Texts’, which risks perpetuating the myth that there is something immaterial, outside the world and supervening on it, when in fact all of experience is equally embodied and disembodied, grounded and dreaming. The early sections of the book do a brilliant job of lancing some of the more cartoonish ways in which we are tempted to talk when we start to think about (what Ingold does not want to call) ‘material culture’. Yet, as in his earlier book, Lines, there is much in Being Alive for thinkers on text–in particular, Part V on ‘Drawing Making Writing’, which traces a dazzling set of connections between the legible, visible and singable letter, between writing, wayfaring, spinning, flying kites and doing anthropology. It’s truly inspirational stuff.